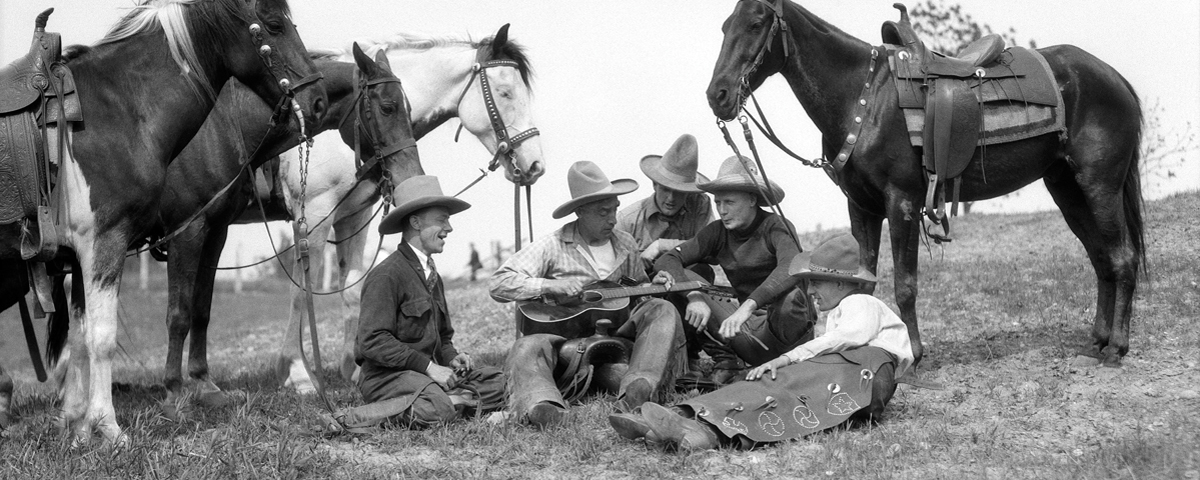

A silvery moon, a sleeping herd, a lonely cowboy riding night guard, crooning a soft cowboy song to soothe the cattle in the long hours before dawn. Such is the ingrained image of the singing cowboy, fixed in our collective imagination by a thousand stories, songs, books and films.

Did it really happen? Probably not much. To date most cowboys do not sing in the saddle, but the tradition has a germ of truth that grew into a natural phenomenon in the 1930s and ’40s, with such legendary singing and acting stars as Gene Autry and Roy Rogers taking the tradition to new heights.

Wherever people have gathered in semi-isolation, a folk music tradition has taken root. In centuries past folklorists and musicologists culled together collections of sea chanteys, lumberjack tunes and the like. By the early 20th century folklorist John Avery Lomax and song collector Nathan Howard “Jack” Thorp had each published collections of cowboy songs. But the tradition was well established by then, harking back to amateur poetry published in stockmen’s journals in the late 19th century and set to music by cowhands with time on their hands.

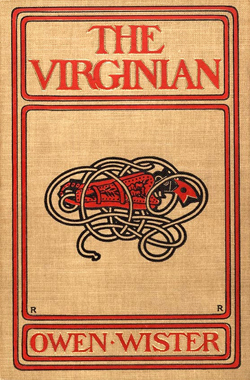

Old World melodies provided another rich source. With lyrics rewritten to fit a Western setting, the Irish folk tune “Green Grow the Laurels” became “Green Grow the Lilacs,” while the English melody “The Unfortunate Rake” became “Streets of Laredo,” to name two of many examples. Serialized stories and novels, most prominently Owen Wister’s 1902 best seller The Virginian, further romanticized cowboy singing, firmly planting the mythical image in the public’s collective mind by the time record companies realized, in the mid-1920s, there was a market for folk, country and blues recordings.

Cowboy songs had made it onto wax phonograph cylinders earlier than that, of course. Debuting in hit stage plays around the turn of the 20th century, songs like “Cheyenne,” “My Pony Boy” and “Ragtime Cowboy Joe” had become popular records, further reinforcing the mystique of the singing cowboy. From the mid-1920s on such colorful performers as Harry “Haywire Mac” McClintock, John L. “Powder River Jack” Lee and wife Kitty, and Carl T. “Doc” Sprague, as well as established singer-songwriters like Vernon Dalhart and Carson Robison, recorded a number of cowboy records. Aside from “Home on the Range” (lyrics written in 1872 by Dr. Brewster Higley of Smith County, Kan., in a poem titled “My Western Home”) and “Red River Valley” (uncertain origins), the songs often addressed the dangers, adventures and sorrows of life on the trail (“When the Work’s All Done This Fall,” “Little Joe the Wrangler,” “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie,” “I Ride an Old Paint”), badmen of the West (“Jesse James,” “Sam Bass,” “Cole Younger”), as well as the occasional bit of cowboy humor (“The Strawberry Roan,” “Tying Knots in the Devil’s Tail,” “Zebra Dun”).

Cowboy singing got its big boost into the saddle with the coming of sound to motion pictures in the late 1920s. Westerns had been a staple of the exploding film industry since The Great Train Robbery and Kit Carson hit screens in 1903. It was only natural the new technology would showcase the cowboy singing trend. The first talkie Western, In Old Arizona (1928) featured Warner Baxter as the Cisco Kid, singing to the lovely but treacherous Tonia Maria, played by Hollywood debutante Dorothy Burgess.

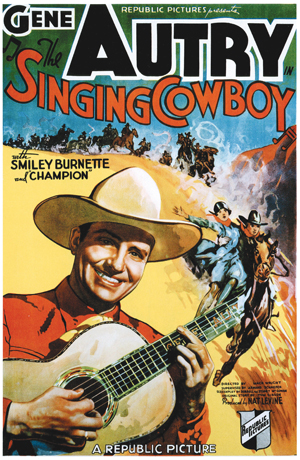

Bob Steele, Ken Maynard and even John Wayne (with dubbed voice as Singin’ Sandy Saunders in 1933’s Riders of Destiny) all tried a hand at singing on film, but it was little Mascot Pictures that took a chance on a Texas-born popular record seller and cowboy radio star named Gene Autry. After a couple of minor supporting appearances, Autry launched into a series of musical Westerns that—implausibly to devotees of the “authentic” Western—became hugely successful. Around the same time Warner Brothers was developing a series starring Dick Foran, but Mascot was quicker on the draw, and while Foran’s films were popular, his big Broadway-style voice did not project the innocence, sincerity and authenticity that endeared Autry to audiences. Republic Pictures (which by 1936 had absorbed Mascot) propelled Autry into stardom, making him one of the most popular celebrities of the era, and his films in turn made Republic a very successful studio.

Hollywood, always eager to jump on a trend, churned out scores of singing cowboy series, and by 1940 every studio but MGM had a singing cowboy star: Tex Ritter at Grand National, Monogram and Universal; Jack Randall at Monogram; Fred Scott at Spectrum; Smith Ballew at Paramount; Bob Baker at Universal; Ray Whitley at RKO, etc. There was a singing Royal Mountie (James Newill), a singing Latino (Tito Guízar), a singing cowgirl (Dorothy Page) and a black singing cowboy (Herb Jeffries, the “Bronze Buckaroo”). In a notable series of features with action star Charles Starrett, Columbia featured the singing talents of the Sons of the Pioneers.

It is worth reflecting on the Sons of the Pioneers, as their contribution to Western music is unsurpassed. Their tight harmony came to represent the sound and style of the West, and in an era when studios were clamoring for new songs, the brilliant songwriting of master poets Bob Nolan and Tim Spencer gave us such enduring classics as “Tumbling Tumbleweeds,” “Cool Water,” “When Pay Day Rolls Around,” “Blue Prairie,” “The Everlasting Hills of Oklahoma” and quite literally hundreds of others.

Perhaps more important, their music evinced a decided shift from the original themes of trail life and tragedy to a new vision celebrating the grandeur and beauty of the West. The songs fit perfectly with the romantic image of a sprawling, unspoiled West and the lone Westerner at peace with himself and his environment.

The third member of the original Pioneer Trio (they became the Sons of the Pioneers after adding instrumentalists Hugh and Karl Farr) was Len Slye, who auditioned for Republic Pictures in 1938 after one of several contract-related walkouts by Autry. Herb Yates, the autocratic founder and president of Republic, determined to make young Slye, renamed Roy Rogers, a superstar in Autry’s place. With Autry’s subsequent return, Republic instead boasted the two most popular singing cowboys in America, to the delight of fans of this Western subgenre.

On the recording side of the trend the mid- to late ’30s boasted record sales for a number of Western songs, not only by cowboy singers like Autry (who ended up selling many millions of Western records, though two of his biggest hits were the seasonal favorites “Here Comes Santa Claus” and “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer”) but also by such big band icons as Tommy Dorsey and Glenn Miller. Perhaps no one had a greater impact on popularizing the genre than Bing Crosby, who, by recording a number of Western classics and starring in the musical Western Rhythm on the Range (1936) basically made the West cool for folks back East.

By the end of the war years the fad had begun to run its course. Of the original singing cowboys of the 1930s only Autry and Rogers (along with his third wife, Dale Evans, whom Roy married on New Year’s Eve 1947) maintained their icon status. Ritter went on to be a hugely popular country singer, though his Western identity (think 1952’s “The Ballad of High Noon”) defined him through the rest of his days. In an effort to inject new life into the genre, the studios developed a new stable of singing cowboy stars, including Eddie Dean, who made the first color singing cowboy movies for Producers Releasing Corp.; Jimmy Wakely at Monogram; Ken Curtis at Columbia; Monte Hale at Republic; and Rex Allen, the last of the singing cowboys, also at Republic.

All fads run their course, and by the early 1950s so had the singing cowboy phenomenon. Autry left for television in 1950, followed by Rogers the next year. In 1954 Allen closed out the decades-long chapter in the film history of the singing cowboy.

Singing cowboys had had their heyday, but Western music was far from dead. Western series were all the rage on television, and Western songs (as well as those memorable TV themes for Maverick, Jim Bowie, Cheyenne, Sugarfoot, Rawhide and the like) featured from time to time within the framework of small-screen plotlines. Marty Robbins sparked a mini-revival in 1959 with such hit songs as “El Paso” and “Big Iron,” and over the next couple decades Western songs popped up on the country circuit (Eddy Arnold’s “Tennessee Stud,” Faron Young’s “The Yellow Bandana,” Billy Walker’s “Cross the Brazos at Waco” and Rex Allen Jr.’s “Can You Hear Those Pioneers?”) and pop charts (Billy Vaughn’s “The Shifting Whispering Sands” and Lorne Greene’s “Ringo”).

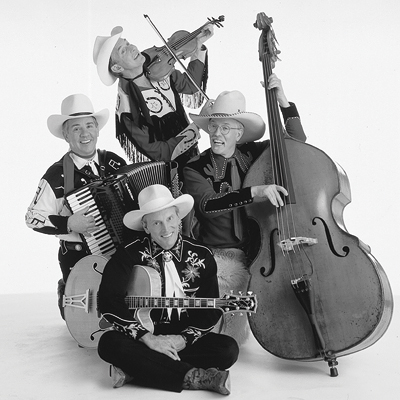

The mid 1980s saw a surprising resurgence in the musical heritage of the West, spearheaded by Riders in the Sky (see sidebar at right) and impelled by the creation of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering in Elko, Nev., as well as the Warner Western music label, which featured nationally renowned recording artists like Michael Martin Murphey, Don Edwards, Sons of the San Joaquin and Red Steagall, as well as the final album—The Bronze Buckaroo (Rides Again)—of singing cowboy Jeffries. The culmination, perhaps, came with the Grammy Award Riders in the Sky garnered for singing “Woody’s Roundup” in Disney/Pixar’s 1999 animated classic Toy Story 2.

Where is Western music today? Still very much on the map. Such fine solo performers as Dave Stamey, Eli Barsi, Brenn Hill, Belinda Gail and the fabulous Quebe sisters (Grace, Sophia and Hulda), as well as popular duo Devon “Jessie the Yodeling Cowgirl” Dawson and Jessie Robertson, have risen to prominence in the genre, while young talents such as Mikki Daniel and Kristyn Harris have spread the sound worldwide. Young singer Kacey Musgraves made a name in the cowboy music genre before branching into commercial country music. Patsy Montana’s signature song “I Want to Be a Cowboy’s Sweetheart” plays over the end credits of John Sayles’ 1996 film Lone Star, set in a Texas border town. Each fall the Western Music Association holds a popular festival, and many of the entertainers mentioned above still actively tour. Indeed, the Sons of the Pioneers—which has successively replaced members as one leaves and another joins—remains to this day a superb singing group after more than eight unbroken decades.

No, Western music is not as ubiquitous as it was in its 1930s and ’40s heyday, when it was on radio, record and film, but the genre has comfortably found its place in the mosaic of American music alongside such folk traditions as Cajun, bluegrass, Delta blues, zydeco and mountain music. It is a sound and style capturing what the world has come to love about the mythical West and the cowboy, a romance too strong to fade. To paraphrase a song by the late country singer and rodeo champion Chris LeDoux, the cowboy is still out there—you just can’t see him from the road. WW

Douglas B. “Ranger Doug” Green is a Western musician, arranger and award-winning songwriter best known for his work as guitarist and lead baritone singer with the group Riders in the Sky. For further reading try Ranger Doug’s own Singing in the Saddle: The History of the Singing Cowboy, as well as Singing Cowboy: A Book of Western Songs, collected and edited by Margaret Larkin; The Singing Cowboys, by David Rothel; Singing Cowboy Stars, by Robert W. Phillips; Cowboy Songs and Other Frontier Ballads, by John Avery Lomax; and Songs of the Cowboys, by Nathan Howard “Jack” Thorp.