Communication Failures Cost Forrest and the Rebels Dearly at Tupelo

[dropcap]T[/dropcap]he summer of 1864 was in many ways the Confederacy’s last gasp for survival. Ulysses S. Grant had gone east to take overall command of the Union Army, but he left his trusted subordinate, Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, to manage affairs west of the Allegheny Mountains. Sherman had his eyes set primarily on the Southern heartland, Atlanta in particular, but had a thorn in his side more troubling than General Joseph E. Johnston’s still formidable Army of Tennessee. Somewhere in Sherman’s rear roamed a dangerous and unpredictable foe: Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, a tactical genius whose unrelenting combativeness and intuitive understanding of men under fire made him more feared than the numbers he commanded.

Forrest was known as the “Wizard of the Saddle” for his repeated successes in the face of much larger Union forces. It was his task to raise havoc along the supply lines and railroads so critical to Federal armies operating in the Western Theater. Most of the food, fodder, and ammunition needed for Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign rode rails stretching from Louisville, through Chattanooga, to his hungry troops and their hard-working horses. That overextended and thinly defended supply line was of course an enticing target for Forrest’s cavalry, which Sherman desperately needed to defeat or keep occupied in Mississippi and Alabama, away from the vital Union rail lines. For that critical assignment, “Cump” hand-picked Maj. Gen. Andrew Jackson Smith and Brig. Gen. Joseph Anthony Mower.

Forrest, therefore, faced two experienced Union generals and 14,000 veteran soldiers with whatever units he could cobble together. On July 5, the Union juggernaut began moving south from La Grange, Tenn., in two columns. The brutally hot weather and clouds of dust made the going slow, and it didn’t help either that Forrest’s troopers immediately began nipping at the Federal flanks as they marched. When the Federals reached Pontotoc, Miss., on July 11, Forrest believed their objective was Okolona—a common target of earlier Union invasions as well as the site of a minor engagement back in February. Forrest would soon find out he was mistaken. The enemy objective was nearby Tupelo.

On July 12, Brig. Gen. Benjamin F. Grierson’s 9th Illinois Cavalry tried to ambush Confederate forces just outside the Union lines, and though it cost him 30 casualties, it further persuaded Forrest that the Federals were headed for Okolona. That assured Smith he could steal a march on his indomitable foe. Feigning an advance toward Okolona on July 13, Smith put his columns in motion toward Tupelo, 18 miles east. If he could get to Tupelo first, Smith could destroy the Mobile & Ohio Railroad tracks there and determine the ground upon which he could best fight Forrest’s troopers.

At daybreak July 13, Forrest advanced to scout the Union position and found Pontotoc deserted. That gave Smith a critical tactical advantage, as Forrest had been forced into the unfamiliar role of reacting to, rather than influencing, Union moves. Confederate district commander Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee, with 2,000 reinforcements, arrived from Jackson, Miss., during the night, and the two generals decided the best option was to attack Smith from the rear and flanks, hoping to delay him or entice an outright fight. At least three attacks on Smith’s disciplined columns that day failed to slow down the Union push toward Tupelo.

Smith and Mower brimmed with confidence. They had outmaneuvered Forrest, allowing Grierson’s cavalry to destroy the railroad track north and south of Tupelo. When the Union column arrived at the hamlet of Harrisburg, two miles to the west of town, Smith deployed his men in a strong semicircular defensive line on a high ridge. That night, they strengthened their lines with fence posts, wood from local houses, and cotton bales. Smith anchored his lines in woods and Grierson’s cavalry screened the flanks and guarded the supply wagons in the rear. The ground in front of Smith’s men sloped down toward a meandering creek. If the Confederates attacked from the woodland beyond it, they would be exposed to artillery and rifle fire for 300–1,000 yards before they could even reach Union lines. By 3 a.m., July 14, Smith’s men were ready for an attack.

Forrest and Lee consolidated their forces about a mile from the Union lines. Whether the two were in agreement about giving battle on July 14 remains a topic of controversy. Major Charles Anderson, Forrest’s assistant adjutant, believed they were not, noting Forrest’s declaration that “[t]he enemy have a strong position—have thrown up defensive works and are vastly superior in numbers and it will not do for us to attack them under such conditions.” But Lee, writing postwar, remembered otherwise: “Whatever others might say, [I] and Gen. Forrest were in perfect accord as to delivering battle.…On this occasion not to fight would have been to have given up the great corn region of Mississippi, the main support of other armies facing the enemy on more important fields.”

Historians also disagree about the soundness of Lee’s battle plan, his first as an independent commander: Three brigades would assault the Union right and

center while Brig. Gen. Philip Roddey’s Alabama regiments would swing around and envelop the Federal left. Brig. Gen. James Chalmers’ cavalry and 700 infantrymen would be held in reserve. Captain Charles Morton, Forrest’s young artillery chief, suggested that all 20 Confederate guns be concentrated on the point of attack. Lee, a trained artillery officer, may have made a tactical blunder, however, by dispersing one artillery battery to each brigade. Moreover, the army’s two wings were separated by more than a mile, yet were supposed to attack simultaneously. Forrest and Lee synchronized their watches and agreed on a specific time to move their respective units forward.

As senior officer, Lee held tactical command. He gave Forrest his choice of soldiers, and Forrest selected Roddey’s troopers—men he had not yet commanded. Although they were veteran soldiers, most were cavalrymen or mounted infantry. Now they were being asked to attack a strongly fortified position, on foot and under fire across hundreds of yards of open ground. Since the Union defenses formed a semicircle, a simultaneous attack required Lee’s regiments to advance at slightly different paces, an unlikely achievement for even the most disciplined infantry regiments. Less than 6,500 Confederates would end up attacking Smith’s 12,000 well-entrenched veterans.

July 14 dawned hot and humid, with no trace of wind. Lee had hoped to lure the Federals away from their strong defenses, but when that failed, he ordered battle about 7 a.m., allowing that timing would be critical to any success. Colonel Edward Crossland’s Kentucky Brigade jumped the gun, however. As Captain J.T. Cochran of the 7th Kentucky later wrote: “After passing through several fields and skirts of woods the enemy was discovered in position behind breastworks….Upon seeing the ardor of the men was such that they could not be restrained; they raised a yell and charged them.” Marching at the double quick across more than 500 yards of open ground, the Kentuckians finally were halted by withering fire 50 yards from the Union line.

Decimated though they were, the Bluegrass boys refused to leave the field. Three times the brigade advanced only to be driven back each time, at a cost of 45 percent casualties. As Crossland concluded: “The failure of Roddey’s division to advance, and thus draw the fire of the enemy on my right flank, was fatal to my men.” But on the right where Roddey’s Brigade under Forrest was supposed to be enveloping the Federal left, there was only silence.

Regiments from Colonel Hinchly Mabry’s Brigade were then fed into the fray, only to be chewed up by relentless and accurate enemy gunfire. Lee then ordered Tyree Bell’s dismounted troopers to advance across about 300 yards of open field. He assured Bell that the reserves would relieve him at the proper time. Bell’s men fired a volley, moved out, and stopped several times to fire before the Union defenders replied. They managed to get within 75 yards of the 12th Iowa Infantry, but a withering volley from the Iowans stopped the Confederates cold. The remnants of Bell’s Brigade fled back to the woods, leaving about 400 dead and wounded in the sunbaked field below the Union lines.

Chalmers had not gone far before Lee arrived and ordered him to send Rucker’s Brigade more than 2,000 yards in full view of the Union gunners to assist Crossland’s men. Even before these fresh troops could move into position, “many of the men,” Chalmers reported, “fainted from exhaustion and the remainder were unable to drive the enemy from his position.” As the general bitterly concluded: “They were unable to accomplish anything.”

The failure of Roddey to attack was apparently Forrest’s call. “The enemy were supported by overwhelming numbers in an impregnable position,” he reported, “and wishing to save my troops from the unprofitable slaughter I knew would follow any attempt to charge his works, I did not push forward General Roddey’s command when it arrived.”

FIGHT FACTS

Tupelo, Miss.

July 14, 1864

CAMPAIGN

Confederate Defense of Mississippi

COMMANDERS

Confederate:

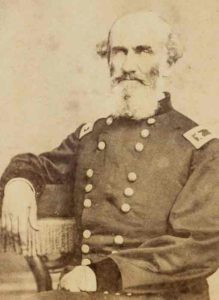

Lt. Gen. Stephen D. Lee

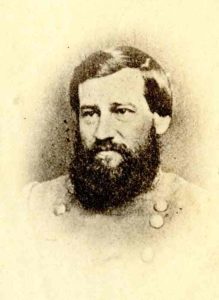

Maj. Gen. Nathan B. Forrest

Union:

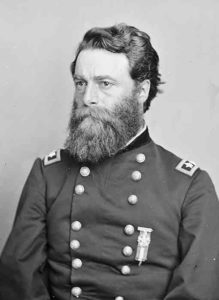

Maj. Gen. Andrew J. Smith

Brig. Gen. Joseph A. Mower

ESTIMATED CASUALTIES

Confederate: 1,362

(215 killed; 1,116 wounded; 51 missing/captured)

Union: 602

(69 killed; 501 wounded, 32 missing)

FORCES ENGAGED

Confederate: Dept. of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana

Union: 16th Corps, 1st and 3rd Infantry, Cavalry Division; 1st USCT

OUTCOME

Union Victory

Writing in 1902, Lee said he confronted Forrest about why the attack had not been carried out. Forrest replied: “[Abraham] Buford’s right had been rashly thrown forward and repulsed. In the exercise of my discretion I did not move Roddey forward, but I have moved him to the left and formed a new line.” Replying that it was now too late, Lee ordered a general withdrawal.

Lee never filed an official report after Tupelo, the only action for which he failed to do so. He never publicly accused Forrest of insubordination nor did he besmirch the general’s reputation. Forrest, in turn, never criticized Lee’s battle strategy or intimated that he would have done things differently if in overall command. One historian does claim, however, that an angry Forrest fumed at Lee: “If I knew as much about West Point tactics as you, the Yankees would whip hell out of me every day.” By noon, the engagement was essentially over, though Forrest would order Colonel William L. Duckworth to make what proved to be an inconsequential attack later that evening. The Confederates ultimately incurred more than twice the Federals’ casualties.

Lee and Forrest expected Smith to attack on July 15, but discovered about noon that the Federals had decamped and were moving north up the Ellistown Road. It struck the Rebel commanders as incredible that Smith would abandon the field and retreat. What they didn’t know was that Smith had significant supply problems—spoiled rations and artillery ammunition shortages. The Confederates clashed with Mower’s rear guard at Old Town Creek that day, but the Federals made it back to Memphis essentially unimpeded by July 23.

Smith and Mower declared the expedition a success, but Forrest had been allowed to continue threatening Union supply lines throughout Middle Tennessee. Within two weeks, an angry Sherman ordered Smith back into Mississippi to continue pursuing the ever-elusive Forrest.

Gordon Berg, a retired civil servant, is a regular contributor to America’s Civil War.