[dropcap]“A[/dropcap]n armored attack is coming down the road!” came an urgent radioed voice from a reconnaissance unit operating ahead of the U.S. 1st Infantry Division. “Don’t fire on us!” Someone logged the entry. It was 5 a.m., March 23, 1943. For the GIs huddled in shallow foxholes and sitting in dank halftracks along a ridgeline southeast of El Guettar, Tunisia, the alert was a surprise; they had spent most of the night preparing to advance—not scrambling to assemble a defense.

Thomas E. Morrison was a soldier in A Company of the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion, attached to the 1st Infantry Division of the U.S. Army’s II Corps. “Somebody came over and kicked me and said, ‘Hey, tanks are coming,’ and about that time, bam, one of them shot through there,” Morrison said. He wasn’t the only one caught off-guard. “We had taken our positions primarily with the idea of defending the artillery against infantry infiltration,” not against tanks, explained 601st commander Lieutenant Colonel Herschel D. Baker. He quickly realized his plan was worthless but did not have time to devise a new one.

Rumbling toward the Americans were elements of Germany’s crack 10th Panzer Division. In the vanguard were more than 50 tanks from the 7th Panzer Regiment, with two panzergrenadier battalions providing infantry support and a unit of motorcycle troops screening the force to the south. In total, the battle group numbered more than 6,000 men.

Facing the onslaught was the 1st Infantry Division’s 18th Infantry Regiment, two battalions of artillery, and the tank destroyers of the 601st. The 10th Panzer Division had crushed foes on the fields of France and on the steppes of Russia; now it turned its sights on American forces in Tunisia. But the men of the 18th had few antitank weapons—which meant that the burden of the defense would fall on the poorly equipped 601st. And within minutes of the initial report, the soldiers manning the tank destroyers realized that the assault was rolling straight toward them.

The 601st’s primary vehicle, the M3 Halftrack, Gun Motor Carriage (GMC), was a sad excuse for a weapon. “Everyone knew this was a joke,” said C Company commander Captain Herbert E. Sundstrom; “Realistically we recognized that the army had to get something quick and this was the stop-gap.” But the simple fact was that despite its name, the M3 tank destroyer—armed with a 75mm gun the French army had developed in 1897, nearly two decades before the first tanks—was lousy at its job.

Snaking toward the American defenses were several panzer variants, including the dreaded Panzer IV Ausf. G, armed with a powerful, long-barreled 75mm gun that could penetrate any American tank from 1,000 yards away. For protection, the G variant had approximately three inches of frontal armor, more than enough to stop the American M3’s gun from penetrating its steel shell, except at point-blank range. The 601st gunners knew this and angled their halftracks for flank shots, where the panzer’s armor was thinner. They hoped the German tankers would oblige them.

The Americans had reason to be worried. The men of the 601st, the 1st Infantry Division, and II Corps had fought the 10th Panzer Division less than five weeks before—at a place called Kasserine Pass, about 50 miles north of El Guettar. There, in the green U.S. Army’s first major encounter with the German army, the panzers and veterans of the vaunted Afrika Korps ran roughshod over American defenses, disrupting Allied offensive plans and denting American morale. By March 17, II Corps had sustained more than 5,000 casualties—with nearly half taken prisoner—and lost 183 tanks, 104 halftracks, 208 artillery pieces, and 512 jeeps—almost all of that at Kasserine. But while the U.S. Army could replace the personnel and equipment, it could not easily replace its reputation, which lay in tatters. After Kasserine, many officers and soldiers in the British Army wondered if their American counterparts had the guts to fight and die for victory.

A. J. Liebling, an American journalist attached to the 1st Infantry Division, also questioned whether his countrymen had what it took to beat a well-trained and experienced German army. Wrote Liebling: “The Germans had done such a job of self-advertising that even Americans wondered whether they weren’t a bit superhuman.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the commander of the Allied forces, knew something needed to change. He started at the top, firing II Corps commander Major General Lloyd R. Fredendall in early March 1943 and replaced him with Lieutenant General George S. Patton, who had successfully commanded the Western Task Force that liberated Casablanca, Morocco, from the Vichy French the previous November.

“I cannot see what Lloyd did to justify his existence,” Patton said of his predecessor. “I have never seen so little order or discipline.” Patton immediately issued new policies designed to whip the soldiers of II Corps into shape, including a strict dress code. All soldiers were required to fasten the chinstraps on their helmets at all times and wear neckties, even in the field. To enforce the policy, he fined soldiers and officers who failed to adhere to the standard. Some of the new regulations did not sit well with the men, but overall, it was a shot in the arm they needed.

The revamped II Corps’ first task: a diversionary offensive to steer Axis forces away from a March 19 attack by British general Bernard L. Montgomery’s Eighth Army on the Mareth Line, a defensive line in southeastern Tunisia the Germans were using to block Allied forces. II Corps was to seize the town of Gafsa and continue east toward Maknassy, threatening an enemy communications line running further east from Gabes—a major Axis supply node on the Tunisian coast.

Fortunately for the Americans, the Italian Centauro Division was defending the area around Gafsa and the town of El Guettar, just to its east. By spring 1943 the Italian army was a beaten force; on March 17 the 1st Infantry Division and the 601st captured Gafsa without a fight.

Buoyed by the easy success, Patton ordered the 1st Infantry Division’s commanding officer, Major General Terry de la Mesa Allen, to push east and capture El Guettar. The previously unimportant village sat astride a highway running between Gafsa and Gabes, on a circular plain tucked between rocky ridges to the north and south. Allen’s division advanced and, by March 22, seized the ridges northeast and southeast of El Guettar, smashing several battalions from the Centauro Division and rounding up hundreds of Axis prisoners. From this commanding position, the division overlooked the Gabes-Gafsa highway and was poised to roll down the road to capture Gabes itself.

German Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, Axis commander of the region, realized the Centauro Division’s collapse had unhinged the entire Axis defense in southern Tunisia:II Corps’ offensive threatened to split the Axis forces in half and cut off the German and Italian units from their supply base. He needed to block II Corps from seizing Gabes—and so ordered the 10th Panzer Division to advance along the Gabes-Gafsa highway to defeat the 1st Infantry Division.

NO ONE ON THE ALLIED SIDE expected the panzers. Still, General Allen’s placement of Lieutenant Colonel Baker’s 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion was prescient. He positioned Baker’s M3 GMCs on the forward slope of a steep ridge—El Keddab, just southeast of El Guettar—like they were atop the inside edge of a bowl. From there they had excellent fields of fire across the El Guettar valley and the Gabes-Gafsa highway just to the south, which Allen believed was the most likely avenue of approach for German forces. With the marshy salt flats of Chott El Guettar to the west and the cradling ridges to the north and south, the enemy would have little room to maneuver.

On the night of March 22 Baker moved out to his battle position. He liked the ground. “East of defensive position and North of the Gabes Road are wadis [dry streambeds] and gently rolling ridges with some knolls,” he later wrote. “It is favorable tank destroyer terrain with dry, sandy soil.”

Baker’s B and C companies occupied locations north of the highway. He placed his single A Company platoon to each side of the road and directed his reconnaissance company to move out in front of the battalion to provide early warning.

Thanks to the reconnaissance platoons, the German attack did not catch the tank destroyer crews completely off-guard. First Lieutenant Joseph A. Gioia, a reconnaissance platoon leader, recalled that around 4:30 a.m., “The silhouettes of foot-troops were seen and the rumbling of tanks were heard. At about the same time two men in a motorcycle and side-car came along the right into our position.”

Within seconds, submachine-gun and rifle fire erupted from the American lines, wounding one of the Germans. The damaged bike rolled to a stop, and several of Gioia’s men detained the bewildered pair of motorcyclists. Scanning the horizon, Gioia counted 16 panzers and two infantry companies approaching. “We opened fire with everything we had,” Gioia said.

The sudden fusillade stunned the panzergrenadiers. After warning the rest of the 601st, Captain Michael Paulick, the reconnaissance company commander, seized the opportunity and ordered his two forward-most platoons to relocate behind B and C companies before the Germans recovered from the shock. Paulick estimated his men had inflicted more than 50 casualties during the brief but violent firefight.

Meanwhile the soldiers in the three tank destroyer companies girded themselves for battle. B Company’s 2nd Platoon engaged the Germans first. “At about 0530 hours, I saw many men coming over a ridge in front of our position,” recalled platoon leader First Lieutenant Robert A. Luthi. “I waited until they were a thousand yards from our position, then I ordered all guns to fire. I observed our shells landing all around the enemy infantry.”

Despite the tempest of fire, the enemy infantry seemed unstoppable. The probing panzergrenadiers found a gap between Luthi’s left flank—to the north—and the rest of B Company. “The enemy infantry kept advancing under our fire, and some of them swept around our left flank,” the lieutenant explained. One of Luthi’s vehicle commanders, Sergeant John C. Ritso, tried to open fire on the flanking Germans to no avail; the panzergrenadiers kept on coming and, said Ritso, “got within fifty yards of our gun position.” Sensing disaster, Luthi ordered his platoon to withdraw to another position—and in doing so, exposed the rest of B Company and the battalion to an attack from the south.

B Company’s 3rd Platoon was closest to the highway; platoon commander First Lieutenant Francis X. Lambert recalled, “As soon as the enemy clearly silhouetted against the skyline, I gave the command to fire. My guns immediately opened up on the enemy.” Tank destroyers rocked as their 75mm guns cracked and boomed. Despite their disadvantages, the M3 GMCs began scoring hits on the approaching panzers.

Corporal Harry J. Ritchie’s gun truck knocked out two panzers within minutes. “Just then to the right I spotted about ten or eleven tanks” about a thousand yards away, another vehicle commander in Lambert’s platoon recalled. They fired about five rounds of armor-piercing ammo, hitting the tanks low and stopping at least two of them.

Lambert tried to raise his company commander, Captain Henry E. Mitchell, on the radio to report success but heard only static. Then he realized Luthi’s withdrawal had left him in a precarious position. “When I looked to the left flank, it seemed to me that all the vehicles in that sector had withdrawn, including two of the destroyers under my command,” Lambert recalled. “This left my two right destroyers completely exposed on the left and right.” The lieutenant pulled out his platoon, but as the halftracks drove away, one hit a landmine. The resulting explosion destroyed the vehicle and wounded most of the crew. A second blew a tire, while a third vehicle’s 75mm gun jammed, leaving Lambert with only one operating halftrack.

Along B Company’s opposite flank, to the north, was 1st Platoon under the command of First Lieutenant John D. Yowell, from Dallas, Texas. His gunners had opened fire shortly after the initial radio warning. Sergeant Adolph I. Raymond, a vehicle commander in Yowell’s platoon, remembered firing on a German tank, likely a Panzer IV: “Five rounds bounced off and the sixth one went home.”

Then Raymond saw a second panzer. This time he knocked it out with one round. But his victory was short-lived when a round from an unseen panzer split open his engine block, wrecking his halftrack. Another vehicle from the platoon destroyed the panzer.

Yowell’s other gunners found their targets. “When the tanks located us they turned completely around and came back over the same route,” Raymond recalled. “I believe they returned because of the impassable terrain and also to put our four guns out of action.” Panzer after panzer brewed up—but not without cost. Yowell lost several halftracks in quick succession. Worse, his remaining trucks were running out of ammunition because they had to shoot five to six rounds to disable each panzer. It was time to withdraw, reload, and fight from a new position.

“Finally we realized that our platoon was about the only one left,” recalled Corporal John Nowak, who served under Yowell. It was then that Lieutenant Yowell distinguished himself. He maneuvered his platoon’s vehicles from hill to hill, always keeping them protected from incoming fire. Says Nowak: “He directed the vehicles to safety and we were the last to leave the area.”

Further to the north was First Lieutenant Samuel B. Richardson, 1st Platoon, C Company. When the panzers appeared, his soldiers performed with the calm efficiency of men on maneuvers. “It was still dark when we opened up, daylight just breaking,” said Sergeant Steve Futuluychuk, one of Richardson’s halftrack commanders. “My gunner sent two tanks up in smoke and I another.”

After several minutes of fighting, Richardson counted seven panzers burning or broken down in front of his platoon position. Before he could relax, German artillery zeroed in on the platoon, showering it with bursting shrapnel. Complicating matters further, he had lost radio contact with most of his men, forcing him to use runners. In the confusion, some of the vehicle commanders, unable to raise Richardson, started to withdraw. Richardson realized he had lost half his platoon only when a runner returned with the news that his southern flank was wide open. Following orders, Richardson withdrew his remaining vehicles.

From his position, Captain Sundstrom, the C Company commander, could see the panzer blitz and ordered his 2nd Platoon to move forward. “It looked a like a parade,” said Sergeant Bill R. Harper, a 2nd Platoon halftrack commander. The 50-plus metal monsters were a daunting sight. But, within minutes, the M3 crews went to work, plugging away at the enemy. “We’re behind the top of the hills,” said Harper, “and we’d pull up and fire and then back down.”

Second Lieutenant Charles M. Munn’s 3rd Platoon was on C Company’s northern flank. At the onset of the attack, German panzergrenadiers assaulted his position in swarms. At one point, two panzers dropped off a mortar crew behind a shallow ridge; the crew lobbed rounds onto Munn’s unit. One exploded above one of the open halftracks, wounding two of the crew. One soldier required immediate medical attention, so Munn hauled him to the rear and then linked up with First Lieutenant John C. Perry, the company executive officer, to secure more ammunition.

The return trip was harrowing. “The Germans must have realized that this was an ammunition halftrack, for the fire laid down on us was quite heavy,” recalled Munn, who was sitting in the back of the M3. Despite the incoming fire, Perry and Munn reached 3rd Platoon and resupplied them.

Meanwhile to the south, Captain Sundstrom found himself surrounded, along with C Company’s 2nd Platoon. “One of our men reported that enemy infantry was coming along the foot of the mountain,” Sundstrom recalled. The captain had to make a difficult choice. He ordered his vehicles destroyed, and sent his men back to the battalion support area in groups of three; there they waited for new vehicles to contin-ue the fight. In Sundstrom’s absence, Perry assumed command of the rest of Sundstrom’s company and chose to fight it out. He ordered Munn to take his two remaining halftracks and another gun truck to defend an artillery unit on the eastern side of El Keddab Ridge.

Looking for an easier target, the panzers swung to the south and tried to flank an A Company platoon. “At this time I counted well over thirty tanks circling to the right,” the platoon leader recalled. “I ordered two of my guns to take them under fire. The combined fire of the artillery and tank destroyer elements on my right turned this thrust back before they had gotten one thousand yards from the hill.”

BY AROUND 8:20 A.M., the German assault was finally faltering. The 601st had lost most of its vehicles—but had inflicted a terrific amount of punishment on the German attackers. Northeast of the 601st, the Germans also had no luck against the 18th Infantry’s 3rd Battalion, where GIs stopped panzergrenadiers cold. Meanwhile, the 32nd Field Artillery, parked behind the 601st, rained death on enemy troops.

More importantly, 1st Infantry Division reinforcements began to arrive, including another tank destroyer battalion and several infantry and artillery battalions. The Germans, however, had nothing left to throw into the fight: they had committed virtually everything in their initial attack. The American line had bent, but it had not broken.

By midmorning, the German offensive stalled and the panzers pulled back. The Axis tried again later that afternoon in an infantry-heavy attack with a handful of hesitant panzers. Journalist Liebling, a witness to that day’s battle, likened the German tanks to “diffident fat boys coming across the floor at a party to ask for the next dance, stopping at the slightest excuse, going back and then coming on again.” But the attack failed. By midnight, generals Allen and Patton realized they had won a great victory.

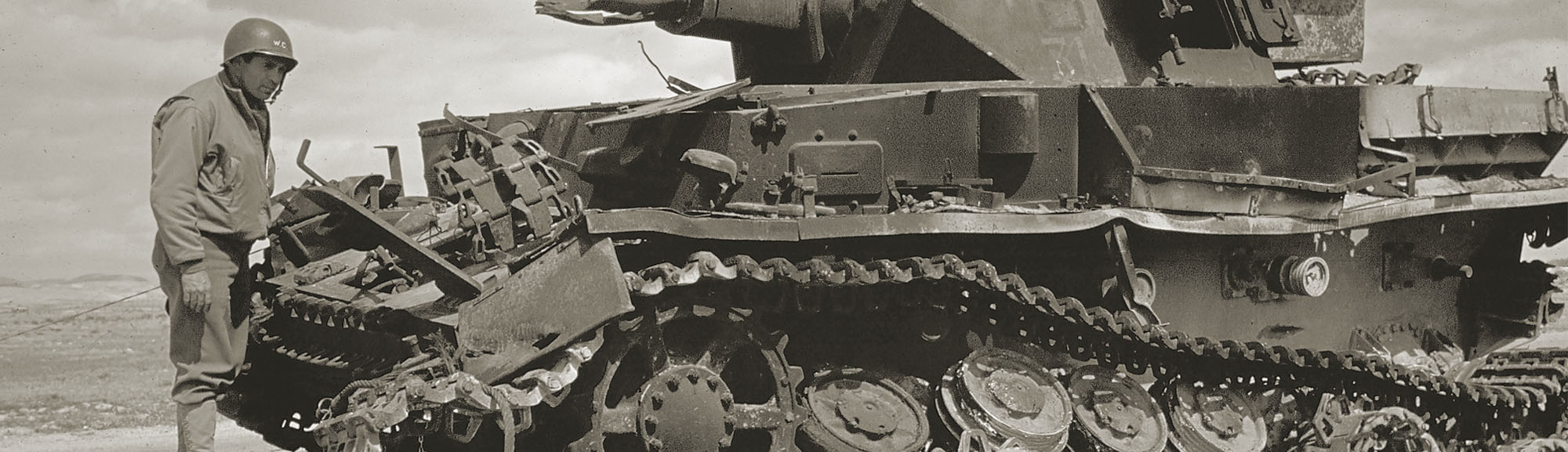

The 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion was instrumental to that triumph. Their advantageous positioning certainly added to their success. But a greater contribution came from the courage and tenacity they brought to a fight in which they knew the odds were against them. Despite losing more than 30 vehicles to enemy fire and suffering 72 casualties, the undergunned and underarmored tank destroyers blunted the main panzer thrust. The next morning, the 10th Panzer Division reported only 26 serviceable tanks—a loss of 50 percent from the previous morning.

Kesselring and the other Axis commanders now knew the Americans learned quickly. Much to their chagrin, the inexperienced junior partner was no longer the Achilles’ heel of the Allied coalition. Two months later, Axis forces in Tunisia surrendered, ending the war in North Africa. For its actions on March 23, 1943, the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion earned a Presidential Unit Citation. They went on to fight in Sicily, Italy, southern France, and Germany.

Shortly after the battle, reporter A. J. Liebling looked back on the victory, and all it implied: “If one American division could beat one German division, I thought then, a hundred American divisions could beat a hundred German divisions.” Time and turmoil would prove him right. ✯