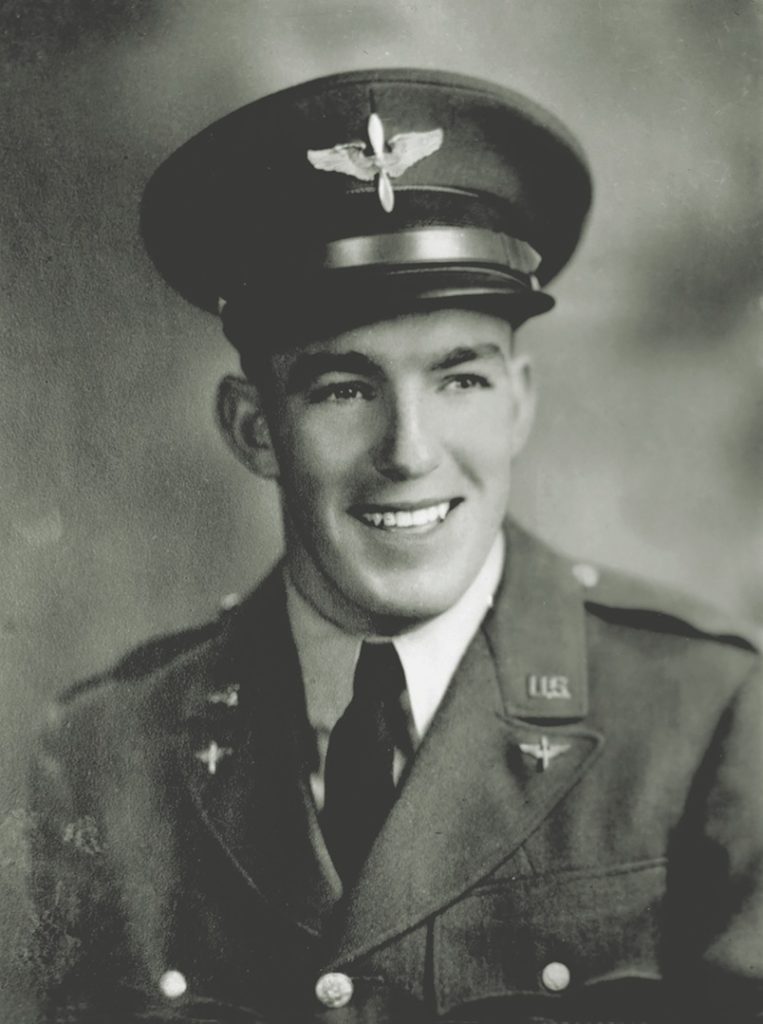

Lincoln Bundy was assumed to have died shortly after D-Day. Fifty years would pass before his family learned otherwise

ON SUNDAY, DECEMBER 17, 1944, a group of Frenchmen was hunting wild boar in the Saint-Sauvant forest in central France. It was a special occasion for those present—the inaugural hunt of the season and the first since the Liberation. As the men tramped along a forest road with dense thickets on either side, they spotted numerous broken branches. Looking closer, they noticed three large areas of disturbed earth. They scraped away some of the soil, first with their boots and then with their hands—and recoiled at what they saw.

The next morning a party of six gendarmes arrived, bearing spades and accompanied by several officials from the nearby village of Rom. Over the course of several hours, they unearthed 31 badly decomposed bodies. A local physician named Maupetit examined the corpses, compiling detailed notes on what remained of the deceased and estimating the time of death as early July. The majority were dressed in identical military uniforms: khaki jackets made from heavy twill with two buttoned breast pockets, and khaki pants with two front pockets and press-stud fastenings. Two men wore identity discs with their names and regimental numbers; one had a tube of Macleans toothpaste, a British brand; another had the manufacturer’s name on his underwear: “Faulat Belfast.”

Doctor Maupetit observed that one corpse was dressed differently from the others. He wore low-laced shoes and a pullover with a label inside reading “Le Mont St Michel,” a French brand. The doctor took note of the man’s wounds: “Bullet in the head, entered right parietal area. Bullet in praecordial region [the anterior chest wall over the heart] and another in central thorax.” He then added: “Presumed to be French nationality.” This corpse was assigned the number 22.

At a short inquest on December 21, three witnesses who lived near the forest testified that they’d heard machine gun fire early on the morning of July 7. One man, Paul Alleau, a member of the local Resistance, said that in late June or early July “approximately 30 British parachutists” had been captured in the region and that their fate was “unknown.” Later on the 21st, the head of the local gendarmerie, Albert Charron, compiled his report on the discovery; based on the evidence, he wrote, all but one of the dead were probably “British parachutists.”

Postmortems completed, the bodies were placed in coffins along with copies of their autopsy reports and glass tubes containing the numbers Doctor Maupetit had assigned each corpse. The same numbers were affixed to the outsides of the coffins. On the afternoon of December 23, the men were laid to rest in Rom’s village cemetery. The 30 soldiers were buried in a communal grave, marked by one long row of headstones and a second shorter row; the man presumed to be a French civilian—probably a member of the Resistance—was interred close by in a plot of his own.

But he was not French, nor was he British. He was an American—but it would be another half a century before his family learned of his terrible fate.

LINCOLN DELMAR BUNDY was born on February 12, 1918, the seventh child of James and Chloe Bundy. They lived on 640 acres of land shared with James’s parents in a rural part of northern Arizona known as Mount Trumbull, but had to travel nearly 60 miles to Saint George, Utah, for their child’s birth, as that was the nearest town with a midwife.

Bundy’s childhood was an idyll. When he wasn’t attending the one-room schoolhouse, he roamed the woods and hills in the company of his brothers and cousins. No one shared his adventurous spirit more than his elder cousin, George C. Iverson, whose homestead was three miles north of the Bundy family’s. With their dogs, Strip and Van Dyke, the pair explored the wilderness, toughening their bodies and developing their characters as they fished, hunted, and climbed.

Bundy had much to commend him as he reached adolescence. Handsome and athletic, he was also bold, intelligent, and ambitious, but the confines of a classroom held no attraction for him. On finishing eighth grade at Mount Trumbull he enrolled at Dixie High School in Saint George but soon dropped out and headed to Kingman, Arizona, about 300 miles south, where he took a job in the mines. The work was tough, but the money was good for a boy of his age. He saved his wages and, in 1936, bought his aunt’s homestead—1,280 acres just south of his dad’s land. Bundy, at just 18, had his own ranch. He aimed to breed the finest horses in Arizona.

War interrupted his plans. In October 1940, one month after Congress passed the peacetime Burke-Wadsworth Act requiring all men between 21 and 35 to sign up with the selective service, he and George registered for the draft. When the United States entered the war neither had been drafted, but they knew their time would soon come. Better to enlist, they agreed, so in January 1942 they drove to Kingman and presented themselves before the U.S. Army Air Forces with a request to become fighter pilots. The recruitment officer took one look at George’s 6-foot-1-inch frame and told him he was too tall. Try the Marines, he suggested, which George did. The 5-foot-7-inch Lincoln was accepted as an aviation cadet.

BUNDY GRADUATED from the 63rd Army Air Forces Flying Training Detachment in Douglas, Georgia, in April 1943, and on May 28 the new second lieutenant received his silver wings at Napier Field in Alabama. That summer, Corporal George Iverson wrote to his mom from his post at the Naval Air Station in Sitka, Alaska. “I got a letter from Lincoln,” he told her. “He has finally earned his wings, now he is a pilot. More power to him, I say, even if I have to salute him if I ever get the chance to see him. If he and I both get through this mess alive, we are fixing to get a plane and chase a few clouds in the far horizon.”

Bundy had also finished his training as runner-up in a sharpshooting contest within the training division, and he was the outstanding track and field athlete of his intake. The future looked promising. First, however, he had some furlough to enjoy—which he did at Mount Trumbull in early June 1943. According to the local newspaper, Utah’s Washington County News, Bundy was “honored with a dance and social in the ward hall, a large crowd attending.”

Lincoln spent August to October 1943 training in Meridian, Mississippi, before being posted, in late spring 1944, to the 486th Fighter Squadron of the 352nd Fighter Group, flying his P-51 out of their base at the Royal Air Force station at Bodney in Norfolk in the east of England. At about the same time, George Iverson sailed for Saipan with the 4th Marine Division. (He would be wounded on the third day of fighting for the island, rejoin his unit about a month later, and die on February 25, 1945, at Iwo Jima.)

On June 10, 1944—four days after the Allies had landed on Normandy’s beaches—the 486th Fighter Squadron took off and headed across the Channel with orders to attack German reinforcements in France streaming toward the beachhead. Bundy had christened his Mustang Rustler; his fighter’s call sign was “Angus White Two.” His wingman, “Angus White Three,” was Second Lieutenant William Reese. In his subsequent combat report, Reese stated: “We had just finished strafing a group of trucks, one of which Lt Bundy destroyed, with our flight leader, Major Stephen Andrew. I rejoined with Major Andrew and when the Major called to Lt Bundy to rejoin the formation there was no response.”

The inexperienced Bundy had had the misfortune to be singled out by one of the Luftwaffe’s top aces, Staffelkapitän (Squadron Commander) Lutz-Wilhelm Burkhardt of Jagdgeschwader (Fighter Wing) 1. He had claimed the first of his victories in Russia in May 1942; on the morning of June 10, Bundy’s Mustang became his 69th—and, as it turned out, last—victim before recurrent malaria took him out of action. Burkhardt’s Messerschmitt Me 109 had latched onto the Mustang’s tail close to the ground and opened fire. Keeping calm, Bundy climbed high enough to bail out.

THE LAST SIGHT William Reese caught of his wingman was over La Mailleraye, a rural village, at 10:15 in the morning. Lincoln Bundy touched French soil for the first time 60 miles south of there, among some trees that lay between the villages of Les Aspres and Crulai. The Normandy beachhead was approximately 100 miles northwest. Bundy had some superficial lacerations on his arms and legs from the tree branches through which he had descended, but otherwise was unhurt.

The first person to reach the pilot was a 24-year-old local, André Renard, who had watched the American bail out as he worked in a nearby field. Renard led Bundy to a hay barn. He couldn’t speak English and Bundy couldn’t speak French, but the Frenchman conveyed the message that Bundy was to remain in the barn. He would return. When Renard reappeared, he was accompanied by a friend, Daniel Laguette; they carried some food and civilian clothes, including a pair of low-laced shoes and a pullover. At dusk the three men walked out of the woods and into Les Aspres, where they entered Laguette’s house. Waiting to greet Bundy was the local physician, Jean de Goussencourt, who cleaned and dressed his lacerations.

Bundy had a decision to make. Should he remain holed up in Les Aspres? Or should he follow the instructions issued to all aircrew in the event they were shot down in France: head south into Spain? Renard and Laguette urged him to stay put; surely it wouldn’t be long before the Americans arrived to liberate Les Aspres. But that felt too passive for Bundy; he believed it was his duty to strike out for Spain on foot—to hell with the fact it was 460 miles south. An outdoorsman of cunning and initiative, he was confident he could reach his objective.

For two weeks Bundy made spectacular progress, traveling by night and sleeping during the day. He covered 160 miles, his only guides the tiny compass sewn into his flying suit and a map of France printed on a silk handkerchief. Friendly peasants provided fuel—some bread in one village, ham and cheese in the next. He plucked fruit from trees and hedgerows and sourced water from wells, drinking fountains, and animal troughs.

By the end of June, Bundy had reached the hamlet of Anzec. It was 10 miles east of the city of Poitiers, in central France; 200 miles southwest of Paris; and still some 300 miles from the Spanish border. He was tired, hungry, and unkempt: more hobo than pilot in appearance. As he prepared to fill his water bottle from a farmyard trough, Bundy encountered a 15-year-old boy, Serge Guillon, just back from his boarding school for the summer. Bundy was soon eating a hot breakfast in the presence of Serge’s father, Raphaël, a member of the local Resistance. Raphaël summoned two of his comrades, Joseph Garnier and Daniel Villey, the latter a lecturer in law at Poitiers University and fluent in English. Forget Spain, the Frenchmen told Bundy; it was an impossible goal. But they had another plan: a group of British parachutists was waging a sabotage campaign from a forest hideout not too far away. They would take Bundy to the British.

The following morning, Saturday, July 1, Bundy donned a jacket over his pullover and pulled on a pair of matching pants. No longer in need of his tiny compass, Bundy gave it to young Serge as a souvenir and then climbed on the back of Raphaël Guillon’s bicycle and rode behind him for 15 miles to the village of Lussac-les-Châteaux. Waiting for them was another Resistant, who escorted Bundy to the forest of Verrières.

AT 9:41 THAT EVENING, Captain John E. Tonkin of B Squadron, Special Air Service—a British special forces unit raised in 1941 to penetrate enemy territory, attack targets, and gather intelligence—sent a message from his forest hideout to SAS headquarters in England requesting an identity check on “a Lincoln Bundy, USAAF.” He sounded American and looked American, but Tonkin was taking no chances on the unknown man brought to his camp a few hours earlier.

Lincoln’s arrival could not have come at a worse time for Tonkin, an experienced guerrilla fighter. Shrewd and intrepid, Tonkin, 23, had joined the British special forces unit in North Africa in 1942 and was captured the following year by the Nazis during an operation in Italy. He wasn’t captive for long, however, successfully leaping from the truck taking him to a Gestapo interrogation and making his way to Allied lines.

For the last three weeks, he and his squadron of 40 men, along with a group of 11 French Resistance fighters, had been operating in an area he described as “lousy with Germans.” Tonkin’s instructions for the mission, codenamed Operation Bulbasket, were to attack the enemy’s line of communications from the south of France to Normandy and sabotage the motorized columns and trains taking German supplies and reinforcements north. Unfortunately, it had soon become apparent to Tonkin that several of his men, newcomers to the regiment, were not psychologically suited for guerrilla warfare. Furthermore, two of his most trusted soldiers were missing from a railway yard sabotage operation.

On top of that, the previous day, June 30, Lieutenant Peter Weaver and three SAS soldiers had arrived at the camp. They had parachuted into the region two weeks earlier and blown a train off its tracks before making their way 50 miles east to join Tonkin. At 33, Weaver was 10 years Tonkin’s senior, and he was disturbed by what he saw as lax discipline. Some of the soldiers were making frequent trips to farms to collect eggs, and young women from the nearby village of Verrières were wandering into the camp to flirt with the British soldiers. Weaver concluded that Tonkin “was getting a little out of his depth with his responsibilities.”

He convinced Tonkin that it would be prudent to move to a new camp, which they did early on Sunday, July 2, taking Bundy with them. Following the advice of the Resistance fighters assisting them, the SAS team relocated a few miles south to a wooded area with a well. But the well ran dry almost immediately, and Tonkin had to lead his men back to Verrières at dusk that same day. He intended to find a new camp the next morning.

Just after dawn, though, the sound of an explosion jolted Lieutenant Weaver awake. “For the life of me I couldn’t think what all the noise was about in my semi-sleepy state,” he recalled. “Then it dawned on me: ‘Christ, we’re being mortared!’”

The Germans had somehow learned of their hideaway. Panic ensued. It was every man for himself. Most rushed down a slope toward a valley—just as their Nazi ambushers had envisioned. They were rounded up and herded onto trucks, except for seven Frenchmen, who were captured and summarily executed, and an SAS officer, Lieutenant Tomos Stephens, who was beaten to death as he tried to slip through the Nazi cordon.

Four Frenchmen and seven SAS soldiers managed to escape, among them Weaver and Tonkin. On July 7, Tonkin sent another message to England: “Betrayed and surrounded by 400 Jerry [Germans], incl SS and 2 field guns. Ordered base to scatter.” He listed those who had evaded capture and calculated that dozens of others, including Lincoln Bundy, were now prisoners of war.

Bundy and the 31 captured SAS soldiers were taken to the headquarters of the Wehrmacht’s 80th Corps in Poitiers, commanded by Lieutenant General Curt Gallenkamp. There they were reunited with the two missing SAS soldiers, who had been captured a few days earlier while on their mission at the railway yard. The Germans took three wounded SAS men to a hospital for treatment.

That evening an officer telephoned news of the capture to the German 1st Army headquarters. Gallenkamp’s men were ordered to shoot the prisoners, in line with Hitler’s Kommandobefehl of October 1942—an instruction to execute all enemy special forces. The general disapproved of the command but, lacking the resolve to challenge it, he instead absented himself from Poitiers on July 5. While the three SAS men in the hospital were dispatched by lethal injection, the task at Poitiers fell to Gallenkamp’s chief of staff, Colonel Herbert Koestlin, and 80th Corps’ senior intelligence officer, Captain Erich Schönig. As Schönig later said at his war crimes trial, he argued that Lincoln Bundy should be spared, as he was an airman, but Koestlin called Bundy guilty by association. Schönig also made another important disclosure—one that explained how the Nazis had learned of the SAS hideout. The two SAS soldiers captured at the end of June had refused to speak until the Sicherheitsdienst—better known as the SD, the intelligence branch of the SS—tortured the camp’s location from the pair.

At 5:30 on the morning of July 7, Auguste Cousson, a gardener living on the edge of the Saint-Sauvant forest, was awakened by “several bursts of machine gun fire and two rounds of cannon fire, followed by several single shots.” They came from the direction of the forest road. When Cousson went to investigate, a cordon of German soldiers ordered him back to his house.

FOR 50 YEARS, the Bundy family believed that Lincoln had died in the June 10, 1944, aerial battle.

Then, in 1995, British historian Paul McCue contacted the 352nd Fighter Group Association seeking background information on the fighter pilot. He took for granted that the association knew about Bundy’s death before a firing squad. They didn’t. For decades the association had made regular pilgrimages to Cambridge, England, to honor Bundy and the 15 other 352nd air-men commemorated on the U.S. Army Air Forces’ “Wall of the Missing” at Cambridge American Cemetery. McCue passed on to the astonished association the information he had mined from British archives—including SAS operational reports, and war crimes trial interviews and court proceedings.

The association contacted Sheriff Glenwood Humphries of Washington County, Utah, asking for help in tracing any of Lincoln’s relatives. As it happened, Lincoln’s younger sister, Nathella, lived just a few blocks from Humphries. The news he imparted was a deep shock to the family. How had it taken so long for the story to reach them?

In March 1945 John Tonkin had written a lengthy memorandum to the British War Office in response to their request for information on the attack. He named Lincoln Bundy and said he was “dressed in civilian clothes.” In addition, Tonkin said that the Frenchmen in their camp “were all shot immediately at Verrieres on 3 July 1944.” Four of them had, in fact, escaped, but they were all, nonetheless, accounted for. In other words, Corpse 22, the one dressed in the “Le Mont St Michel” pullover and the low-laced shoes, could only be Bundy.

Complying with a request from the U.S. Army’s Graves Registration Service, their British counterpart exhumed Bundy’s body in 1945 and handed it over for conclusive identification. Yet the Central Identification Laboratory reported that the “released remains were not those of the American decedent [and] were resultantly designated as unknown X-331.”

Continuing their attempt to locate Bundy’s body throughout the 1940s, the Americans appealed to the British to exhume the other corpses that had been buried at the same time at Rom Cemetery, but to no avail. The British were adamant that they had handed over the requested remains; the rest were British soldiers, and they would rest in peace. The corpse designated X-331 remained in American possession until 1950, when it was returned to the British and buried in Rom Cemetery in an individual plot. The British then informed the U.S. Embassy in London that “we have assumed future responsibility for the care and maintenance and permanent marking of the grave of 2/Lt Bundy, U.S.A.A.F.”

Nevertheless, there was further correspondence on the subject in 1951 when the State Department in Washington, D.C., informed the U.S. ambassador in London that “through an administrative error the remains of Lt Bundy have not been recovered.” Consequently, the adjutant general, Major General Edward F. Witsell, declared that “there is insufficient information as to the fate of Lt Bundy to establish the fact of death and place of burial.”

This was not strictly true. John Tonkin and other SAS survivors had testified to an SAS war crimes investigation team that Bundy was in the camp when it was attacked, and in 1947 several Germans officers were convicted by a British military court in Germany of the murders of the SAS soldiers and of Lincoln Bundy. In all likelihood, the lines of communication between the various bodies investigating the case—one of many thousands in the years immediately after the war—broke down, and the dots of information remained unconnected.

Much of this confusion started with the likely error made by the Central Identification Laboratory which, in fairness, had little to work with. They compared Bundy’s dental records with the shattered teeth of the deceased and concluded they weren’t one and the same. The British considered the matter closed and reinterred the corpse in 1950; however, when the official Commonwealth War Graves Commission headstone was erected the next year over Bundy’s grave with his name engraved in the stone, they did add “Buried in this or the nearby communal grave”—the one holding the 30 soldiers—in recognition of the American doubt. It is the only headstone among the 31 to have such an inscription, even though 14 of the 30 other corpses were not positively identified.

Incredibly, none of this was communicated to the Bundy family—with the first news coming from Sheriff Humphries in 1995. In the summer of 2002, six of Lincoln’s cousins made a pilgrimage to France to visit his execution site and final resting place. Their trip coincided with an official SAS commemorative tour, and among the visitors were several wartime members of the regiment and the 16-year-old grandson of John Tonkin. The most emotional moment of the trip came when the Bundys were introduced to a small, 73-year-old man. Fifty-eight years earlier, Serge Guillon had seen Lincoln at a trough in the hamlet of Anzec, an encounter he had never forgotten. The elderly Frenchman (who died in 2020) had a gift for the Americans, something that Lincoln had presented to the teenage schoolboy in June 1944. It was his tiny compass.

Lincoln had hoped that the compass and his own capability would guide him to freedom, but by a cruel twist of fate they directed him to a Nazi firing squad. ✯

This article was published in the June 2021 issue of World War II.