Archival footage from the 1951 newsreel shows a sleek twin-engine jet being towed out of its hangar onto the runway of a remote Royal Air Force base in Northern Ireland. The British commentator intones: “Great hopes center on the Canberra, Britain’s first jet bomber. She’s a top secret, a little something nobody else has got.” The camera pans to the crew, lingering on the test pilot, RAF Squadron Leader A.E. Callard. “He makes a careful study of wind and weather and every crucial detail which must be mastered for the occasion.“We learn the Canberra’s crew is about to embark on a 2,100-mile nonstop flight between Aldergrove, Northern Ireland, and Gander, Newfoundland. The narrator continues, “They are aiming to make the hop in record time.”

And so they did. On February 21, 1951, English Electric Canberra serial no. WD932 made the first direct, nonrefueled Atlantic crossing by a jet aircraft—in a new unofficial record time of 4 hours and 37 minutes. A few days later, Canberra WD932 went on to win a U.S. Air Force competition at Andrews AFB in Maryland, eventually getting the nod to become the Air Force’s new twin-engine bomber-interceptor. During the course of 1951, WD932 became something of a celebrity, serving as a symbol of Anglo-American cooperation and as the pattern aircraft for the B-57 program.

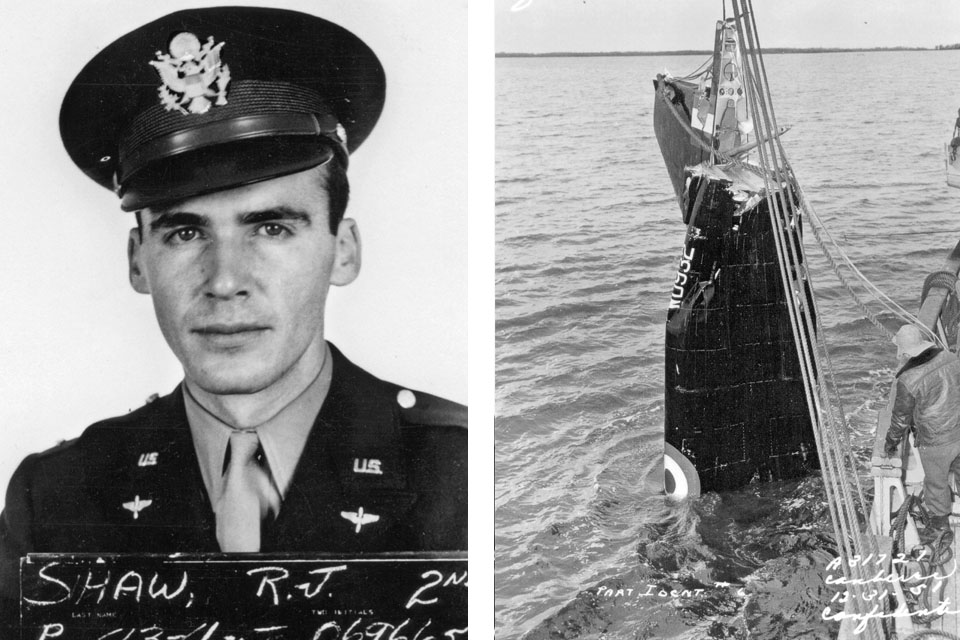

For me, this particular airplane was more than just a promising new jet or brief media star. Ten months after its record-setting flight, on December 21, WD932 crashed during a test flight over Centerville, Md. The pilot parachuted to safety, but the engineer-observer was killed. That man was Captain Reid Johns Shaw, my father. He was 29 years old.

By any standard, the English Electric Canberra was one of the most successful military airplanes ever built. Rarely has any aircraft served so long or so well. The Canberra became operational with the RAF in 1951, and served in various roles until retired from service 55 years later, in 2006. It proved to be extremely versatile, utilized by the air forces of 14 other countries, including Australia and the U.S., both of which flew it in combat in Vietnam.

At the dawn of the jet age in 1945, the RAF envisioned a new jet aircraft as a replacement for its de Havilland Mosquito fighter-bomber, operating primarily at high altitude in a radar bombing role. The Canberra, designed by W.E.W. “Teddy” Petter, was intended to fill that role. During its test program phase, the aircraft was named after the Australian capital, following the RAF practice of naming British bombers after cities.

On May 2, 1949, the first Canberra A1 prototype, VN799, resplendent in all blue, was rolled out of its hangar for ground runs and taxi tests. Much was at stake during the first flight, on the morning of May 13. Some had suggested the project was doomed from the start because the English Electric Company lacked aviation experience. If successful, however, it would put Britain into the forefront of world aviation technology.

Shortly before the morning briefing, in a discussion with test pilot Roland Beamont, aircraft designer Petter had suggested that since it was Friday the 13th, he would not argue with delaying the flight until the next day. But Beamont was ready to fly. Notwithstanding Petter’s superstitious fears, it turned out to be a lucky day with a successful first flight. The only uneasiness Beamont experienced during the flight was a sharp directional jerk each time he applied rudder pressure. Ultimately, this resulted in the rounded top of the Canberra’s rudder being trimmed down to its characteristic squared-off appearance.

On subsequent flights, Beamont discovered that the Canberra handled more like a fighter than a bomber. With its low wing loading and twin-jet power, the new bomber performed better than most fighters of the period. Although acrobatics had not been written into the design requirements, there was nothing to limit the airplane from rolls and loops when flown within the design limits of speed and G forces.

Beamont prepared a flight routine for the upcoming Society of British Aircraft Constructors’ Flying Exhibition and Display at Farnborough in September 1949. As expected, the airplane stole the show. Aviation Week reported:

Canberra Shows Off—biggest military surprise of the show was the English Electric Co. Ltd sky-blue Canberra jet bomber. U.S. observers were not impressed with the Canberra’s straight wing and somewhat conventional configuration on the ground. But in the air the combination of test pilot R.P. Beamont and the 15,000 lb thrust from the two axial Avons made the Canberra behave in a spectacular fashion….

Beamont whipped the bomber (designed to carry a 10,000 lb bomb load) around on the deck like a fighter, flying it through a series of slow rolls, high speed turns and remarkable rates of climb. The Canberra was originally designed for radar bombing at around 50,000 ft, but Beamont’s demonstration convinced many Britishers the new bomber may prove to be another Mosquito in its versatility at everything from low-level attack through high altitude bombing.

More Canberra Content

American military observers at this and other early demonstrations of the Canberra were as impressed as their British counterparts, but they could not envision a role for the new bomber. As one reporter said, “It is neither fish nor fowl.” The Canberra was considered too large to be a fighter and too small to be a bomber. It fell into the same class as the Mosquito, for which there was no American counterpart.

With the outbreak of the Korean War in June 1950, however, the U.S. Air Force needed a replacement for its aging twin-prop Douglas B-26 (previously A-26) Invader. The B-26 was the only U.S. medium bomber suited to low-level interdiction, but attack with the Invader was purely visual, and its numbers were dwindling. At wartime attrition rates, the B-26 inventory was forecast to be depleted if the war continued to 1954.

According to Lt. Gen. Earle E. Partridge, speaking from the bitter experience of his Fifth Air Force in Korea in 1951, “I believe the paramount deficiency of the USAF today…is our inability to effectively seek out and destroy the enemy at night.” Not only was there no effective night intruder available for Korea, there wasn’t even one on the drawing board of any American aircraft company. But by the time the Korean War broke out, the first production model of the English Electric Canberra had already flown.

An Air Force committee formed in the summer of 1950 was tasked with evaluating all available American, Canadian and British aircraft, to see which one could be most quickly adapted to fill the night interdiction role. The selection was to be made from existing models, since creating a new design would add years to development time. American aircraft to be considered were the Martin XB-51, North American B-45 Tornado and North American AJ-1 Savage; foreign designs were the Canadian Avro CF-100 Canuck and the English Electric Canberra.

Consideration of the Canberra as a night intruder was based on an examination of the aircraft in Britain by USAF officials. Earlier that summer, a group led by Brig. Gen. Albert Boyd of the Air Materiel Command went to England and was enthusiastic about the new bomber in many respects. The Canberra’s crew facilities, however, were rated as marginal. Although the pilot had adequate working room, overhead clearance was limited. The navigator sat in a cramped “black hole” behind and below the pilot, with little room to work. Emergency escape for the pilot was by blowing the canopy; the navigator escaped via a hatch located above his seat. Ejection seats were in place for both.

After several months of evaluation by the board of Air Force officers, the final selection was to be made based on competitive flight demonstrations and comparisons at Andrews AFB, outside Washington, in November 1950. The delayed arrival of Canberra WD932 pushed the fly-off to February 26, 1951, though its record-setting Atlantic crossing created buzz for the airplane.

While there was little doubt the Canberra would outperform its competitors, the flying demonstration was considered necessary to silence those who were opposed to accepting a foreign aircraft in the U.S. inventory. The last such example to see active service had been the de Havilland DH-4 of World War I. A strong contingent felt Martin’s XB-51 was the best choice, but no firm decision could be made without a rigorous fly-off.

Former RAF Wing Commander Beamont, now chief test pilot for English Electric and the Canberra test program, would fly the British entry. Beamont’s first reaction to the tight flight schedule was disappointment, since he felt it limited his ability to show off the Canberra’s capabilities. When asked if the schedule could be varied to suit a particular aircraft, he was firmly told, “No, this is an Air Force trial and not a Farnborough show!” However, Beamont calculated that he could complete the set maneuvers in about half the allotted time, and no one had said anything about what could or couldn’t be done with any remaining time.

Making full use of the controllability afforded by the Canberra’s low wing loading, Beamont took WD932 though all its set maneuvers. When he completed the final turn and approached the runway with gear and flaps down, he still had about four minutes left of the 10-minute time slot. Putting the time to good use, Beamont snapped up the gear and flaps, applied full power and zoomed back up 1,000 feet above the dazzled spectators, then made a tight 360-degree turn and a spiral dive before landing with a minute to spare.

After the fly-off, the Canberra seemed to be the obvious winner. Nevertheless, the board could not unconditionally recommend its procurement until certain modifications were made and more information was obtained from the British concerning their ability to deliver the requisite number of aircraft. Those factors and the strong support for the Martin XB-51 resulted in both airplanes being named temporary “winners.”

Since English Electric was unable to supply Canberras to both the RAF and USAF quickly enough, the British agreed to allow the Glenn L. Martin Company to produce it under license in the U.S., assuming the XB-51 lost out. Martin agreed, since it would ensure them a much-needed contract, though naturally they preferred to work on an airplane of their own design. It was during this period of indecision that the B-57 designation was assigned to the American version.

At Boyd’s suggestion, the USAF board requested the loan of a completely equipped Canberra for a more thorough critical evaluation. In March WD932 was delivered to Martin as its first pattern aircraft. The decision to go with the Canberra was made on March 23, when the Air Force sent a letter to Martin requesting 250 B-57As. English Electric delivered a second Canberra, WD940, on August 31. Martin would go on to produce more than 400 B-57s in various configurations.

Tragedy struck the Canberra project during an evaluation flight just before Christmas 1951, when WD932 crashed in Chesapeake Bay off the Delmarva Peninsula, not far from the Martin factory. Both crewmen ejected, but Captain Shaw’s chute failed to open and he was killed. It was a significant setback for the B-57/Canberra program.

The Air Force crash investigation determined that WD932’s left wing had failed just outboard of the engine nacelle as the pilot pulled 4.8Gs at 420 knots during a tight turn. By process of elimination, it was suggested that improper use of fuel tanks—emptying the fore tank first rather than the rear tank— resulted in the center of gravity moving far aft, causing the aircraft to pitch up and become longitudinally unstable.

Neither crew member was able to carry out the proper ejection procedure, which involved manually blowing the canopy and navigator’s hatch before seat ejection. Both the pilot and the navigator ejected through the canopy and hatch, respectively. This was likely the result of the high G-forces. Some believed that my father would have lived had he not been knocked unconscious during ejection, since he died from drowning, and the injuries he sustained during the ejection were relatively minor.

Naturally, there was concern in Britain about the Canberra’s structural failure. Chief test pilot Beamont duplicated the flight with another Canberra to confirm the original test conditions while the U.S. investigation was still underway.

Beamont reported: “I re-proved this case at Warton a few weeks later in another production B2, WD958, to 5.2G at 450 knots, before we knew the results of the analysis. Subsequent calculations showed that with incorrect fuel management on that fatal flight, the C.G. [center of gravity] could have moved well aft of the aft limit and when pulling the G-force tests, the aircraft could have pitched up to 6½ to 7G.” His willingness to repeat the recently fatal maneuver before knowing the results of the crash investigation was a gutsy move.

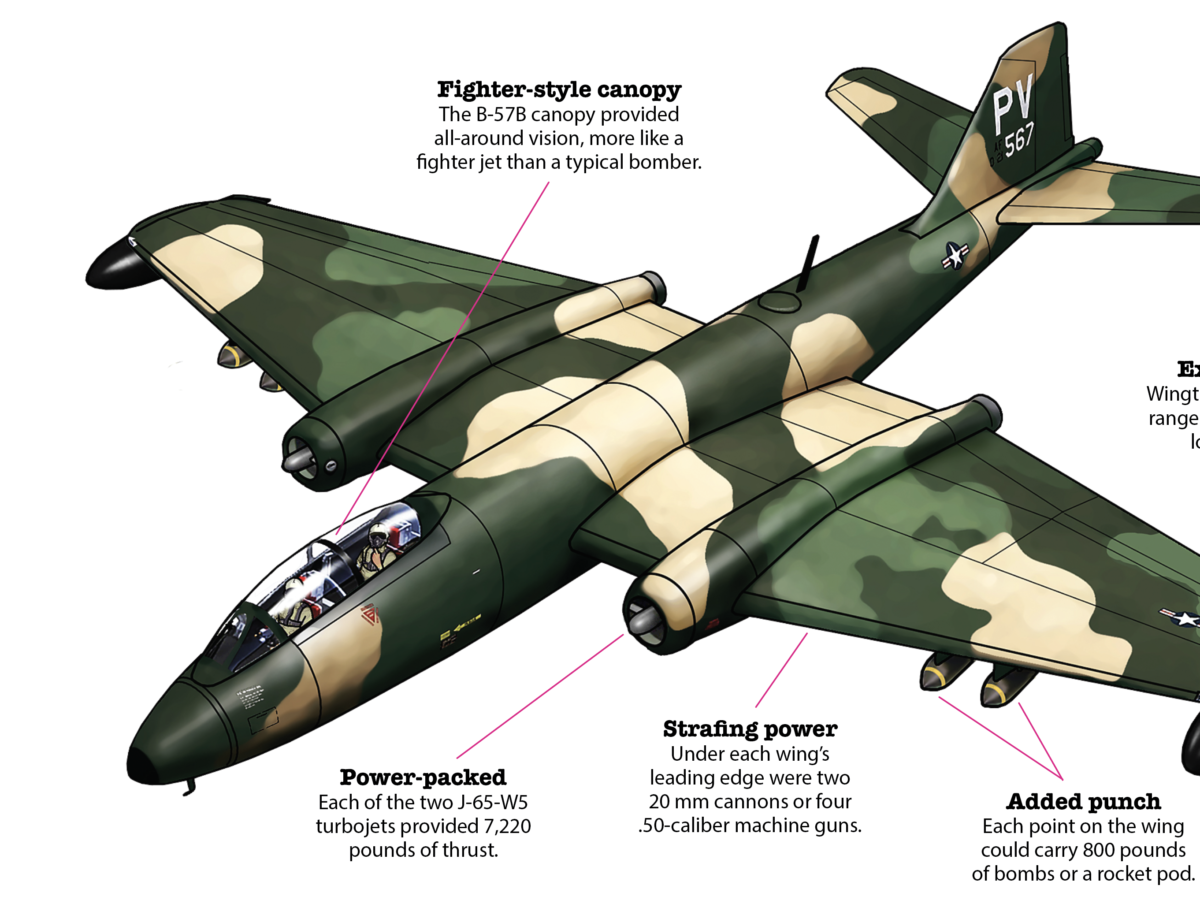

After the fatal crash, the Air Force brass called for changes and improvements to address a number of perceived deficiencies. Among the significant modifications in subsequent B-57B models was a much-improved tandem canopy. This represented a considerable upgrade for the pilot, who gained far greater visibility. Of equal importance, it moved the navigator from the compartment deep behind the pilot, with only a small window, to a position where he could see out of the aircraft and be in a better position to eject, if necessary.

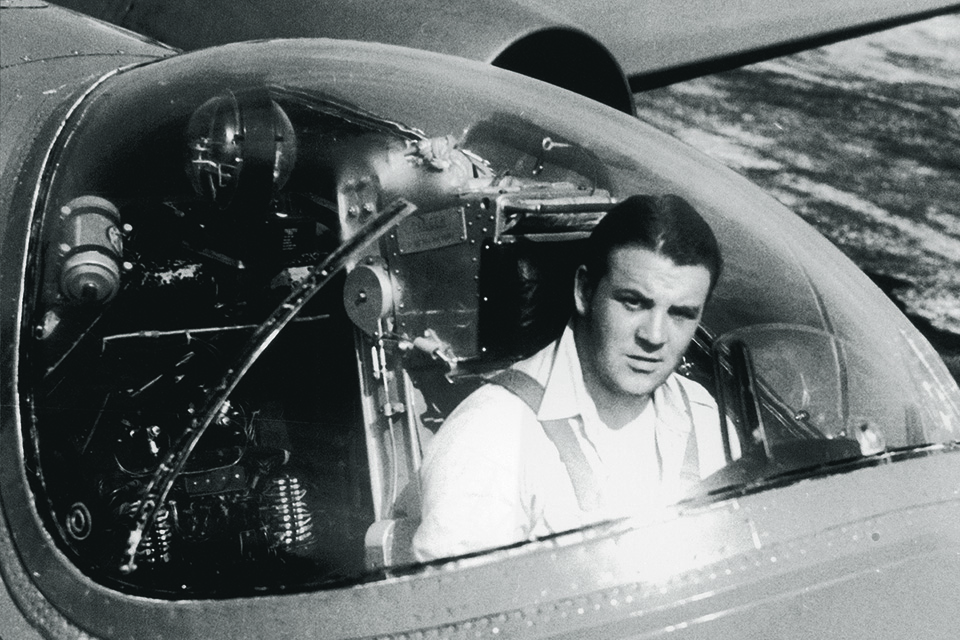

As for the crew of WD932, the pilot was Major Harry M. Lester, who had been part of a record-setting USAF team of F-84E Thunderjets at the Bendix Trophy Races in 1949. Captain Shaw, the engineer-observer, had enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces in early 1942, shortly after the Pearl Harbor attack. He completed pilot training at Lubbock Air Field in Texas in 1943, and was assigned to fly B-24 Liberators. He would remain Stateside as a pilot instructor for the remainder of the war. Taking advantage of the GI Bill, he graduated with a degree in aeronautical engineering from Purdue University in August 1949 on the day after I was born. He was called up as a reservist at the outset of the Korean War, and assigned to the Canberra project.

When Canberra WD932 crashed on December 21, 1951, the Air Force lost more than an iconic aircraft. It also lost a proficient pilot instructor, test engineer, dedicated officer and family man. Captain Reid Johns Shaw gave “the last full measure of devotion” to his country. I am proud to be his son.

Rich Johns (formerly Shaw) Matthies writes from Seattle, Wash. For additional reading, he recommends: Martin B-57 Canberra: The Complete Record, by Robert C. Mikesh; English Electric Canberra, by Roland Beamont and Arthur Reed; and English Electric Canberra and Martin B-57, by Barry Jones.

This feature originally appeared in the September 2013 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.