In 1943 it took just 143 days for Lockheed designer Clarence“Kelly” Johnson and his elite team of 128 Skunk Works engineers and fabricators to create the P-80 Shooting Star. But had it not been for the British, all they would have displayed on rollout day was the world’s fastest glider. It would have had no engine. The United States had so thoroughly forsworn jet engine development that it lagged behind even Italy, to say nothing of Germany and Britain.

It was not for lack of trying. In the late 1930s, Lockheed had started work on an axial-flow turbojet called the L-1000. It was designed by Nathan Price, a creative Lockheed engineer who, not surprisingly, would go on to contribute heavily (and anonymously) to the P-80 design. Price had already invented a cabin-pressure regulator for the Boeing 307 that made airliner pressurization practical, and he was credited with making the Lockheed P-38’s turbocharging system a success.

British designer Frank Whittle had invented the jet engine (in parallel with the German Hans von Ohain), and by the time the P-80 was envisioned, the only Allied turbojets in limited production were the Whittle W.1 and de Havilland’s Halford H-1, a cleaned-up version of the W.1. In the fall of 1940, in the midst of the Battle of Britain, the British sent to the U.S. all of its jet engine, radar and proximity-fuze research, as part of the Tizard Mission, named for British radar pioneer Henry Tizard. The ostensible purpose was to persuade the neutral U.S. to turn its production capability toward manufacturing this emerging technology. But an unspoken motivation was that after Dunkirk the British feared they might well lose the war and if that happened they wanted the U.S. to inherit their weapons technology.

In April 1941, General Henry H. “Hap” Arnold learned of the Whittle-powered Gloster E.28/39 prototype, the first Allied jet to fly, during a secret tour of the British aircraft industry. He was stunned, though he was already aware of the German jet genesis. That September, a U.S. Army Air Corps officer with a briefcase of Whittle W.1 blueprints handcuffed to his wrist flew from England to Lynn, Mass., where the General Electric Company, already well-versed in turbine technology through its turbochargers, set to work building what would ultimately be called the J33 turbojet engine. In its early form, two of them would power America’s very first jet, the Bell XP-59.

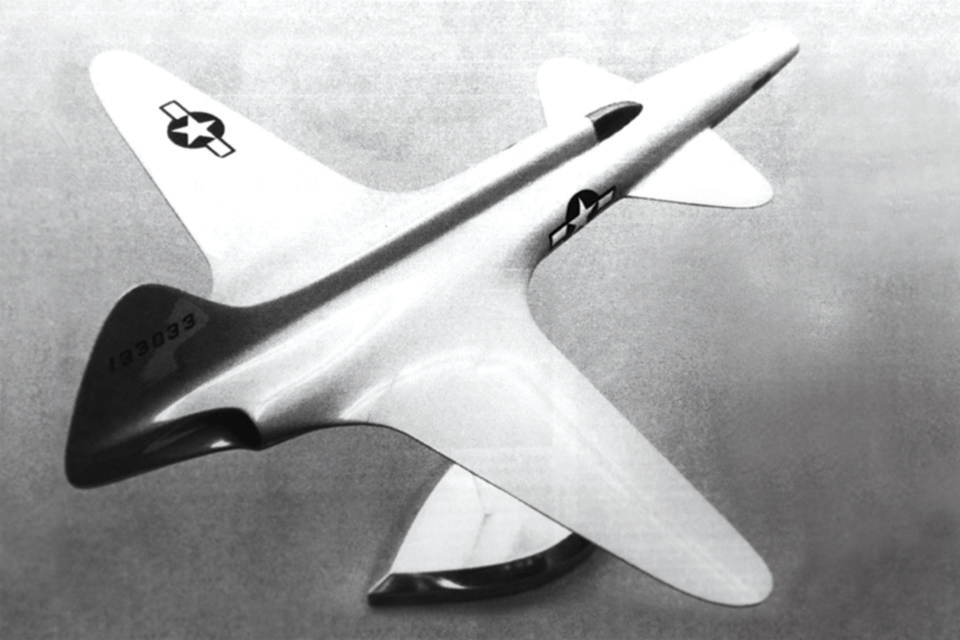

Lockheed had been lobbying hard for the contract to build that airplane. After all, the company had already created, at least on paper, the earliest American jet fighter, to be powered by the L-1000 engine. Lockheed’s L-133, again designed largely by Nathan Price, was an exotic blended-wing/body canard with slotted flaps and low-drag twin engines mounted inside the fuselage.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Yet the War Department told Lockheed to lay off pursuing jet technology any further and to put its effort into building and improving the P-38 Lightning. The company could play with jets after the war. But in the spring of 1943 U.S. intelligence revealed that Messerschmitt was preparing an airplane that would become the only jet to see air-to-air combat during World War II: the Me-262. (The Gloster Meteor did shoot down V-1 buzz bombs but never a manned aircraft.) The U.S. needed a fighter with another 100 mph of airspeed—and quickly.

So why did Bell initially get the nod to come up with a jet? Some say it was because of the company’s reputation for creating outside-the-box designs such as the twin-engine pusher YFM-1 Airacuda and the tri-gear, mid-engine P-39 Airacobra (with the company’s pioneering helicopter work yet to come). Others suggest that Bell was less encumbered than other airframers with work building critical fighters, bombers and transports.

The P-59 was a why-bother design, even though it was in a sense a proof-of-concept project never seriously intended to be a fighter. It turned out to be 50 mph slower than the P-40 and 75 mph slower than early P-47s and P-51s. That didn’t stop Bell chief test pilot Jack Woolams from frequently working his favorite prank: pulling alongside cruising P-38s and the like with his propless mystery plane while wearing a gorilla mask and a derby, smoking a cigar.

When the need for an Me-262 beater became obvious, Bell was ordered to supply all of its P-59 documentation to Lockheed, especially the work done in preparation for the XP-59B. Not to be confused with the production P-59B, the XP-59B was intended to be a much-improved single-engine version of the P-59. To this day there are Bell fans who insist the P-80 was just a cleaned-up version of the XP-59B, a claim that one suspects would have had Kelly Johnson doing lomcováks in his grave.

The very first XP-80 prototype, informally called Lulu Belle, was powered by a de Havilland Goblin engine provided by the British. In fact, the Brits gave Lockheed two Goblins, both originally intended for the de Havilland Spider Crab, which would become the Vampire. They were at the time Britain’s only functioning Goblins. Lockheed needed the second Goblin because it had ignored de Havilland’s warning that the intake ducts had to be strongly built due to a powerful low-pressure area inside each duct. During a ground run, Lockheed’s too-thin ductwork imploded, sending debris through the engine and ruining it.

Lulu Belle had been built under a used circus tent ringed by a bunch of battered wooden pallets. Lockheed was busy with production programs ranging from Army Air Forces fighters to Navy patrol bombers, and it had no room to spare for an off-brand experimental program. The tent quickly came to be called the Skunk Works, and since it was far from all other Lockheed buildings, Johnson could operate it under his own rules.

The XP-80 first flew in January 1944, from Muroc Army Airfield. Within five minutes, test pilot Milo Burcham was back on the ground, spooked by the sensitivity of the controls. “You’ve got a 15-to-1 [aileron] boost and a hot ship that’s naturally sensitive,” Johnson told him. “Maybe you were overcontrolling.” Mollified, Burcham tried again and on his second flight had Lulu Belle up to an unprecedented 490 mph. Lulu Belle would soon notch a speed of 502 mph, making it the first U.S. aircraft to exceed 500 in level flight.

The second prototype, the XP-80A, was a quite different airplane—almost two feet longer and wider in wingspan, 25 percent heavier and with 1,000 pounds of additional thrust from its Whittle-based GE engine. That GE I-40 would become the J33, the engine that in various versions powered every P/F-80, T-33 and even early F-94 Starfire ever manufactured.

Lockheed put a rudimentary back seat into the cockpit for Johnson. From it he solved the problem of “duct rumble,” the noise produced by warring airflow deep inside the engine intakes. Johnson deduced that it was caused by a turbulent boundary layer of air interfering with a smooth flow into the engine. The solution was the louver-like, boundary-layer-eating air scoop that can be seen just inside the intakes of every production airframe thereafter.

With no engine or prop up front and the four .50-caliber guns removed, the P-80’s nose bay afforded room for a second pilot. This opportunity was exploited for tests of a prone-pilot position to reduce the effects of high-G maneuvers. With a canopy and flight controls installed, the test pilot was able to demonstrate at least some resistance to G forces. He was also able to demonstrate how quickly he became nauseated and how difficult it was to fly the airplane while lying down. Another problem: He could fly maneuvers that overstressed his safety pilot, sitting upright in the cockpit behind him.

Another unsuccessful P-80 experiment involved motorizing the machine guns so they could be cranked into a full-upright firing position, a concept likely borrowed from the fixed but semi-upright guns the Germans called Schräge Musik. As it was with the Luftwaffe, the intent was to fly under invading bombers and fire upward into their bellies. But the hammering recoil of four .50s drove the P-80’s nose down, making it impossible to aim the guns.

One unmistakable Shooting Star component was the airplane’s shapely, tapered wingtip fuel tanks. The XP-80A was the first of the line to carry tip tanks and the first airplane in the world to be fitted with them. Johnson invented the tip tank and in May 1944 patented the idea. His patent application cagily shows an airplane with a P-80 planview, but with a propeller and without the jet intakes or exhaust.

Johnson’s tip tanks slightly reduced the P-80’s total drag since they acted as wingtip endplates and reduced tip vortices. They also improved roll response and helped with spanwise loading of the wing. The only thing they didn’t do, with a capacity of just 165 gallons each, was substantially increase range.

Early P-80s had an abysmal accident record—not necessarily through any fault of the airplane but often because of the inability of propeller-trained pilots to operate them properly. Even the most experienced fell to the needy P-80’s demands. Milo Burcham died in the third production prototype when its engine flamed out on takeoff in October 1944. Another killed American ace of aces Richard Bong on the day the U.S. dropped an atomic bomb on Hiroshima. (Bong had only himself to blame. In an age that largely skipped checklists, Bong, with only four hours and 15 minutes of P-80 time logged, forgot to turn on his P-80’s auxiliary fuel pump for takeoff.)

There was an ace-of-the-base mentality among many returning WWII combat pilots, who were used to the near-instant responsiveness of piston engines and the controllable drag of huge propellers that could be shifted in and out of flat pitch. They didn’t need anybody to teach them how to fly a new airplane, but the P-80 offered no such flexibility. New Shooting Star pilots would find themselves approaching a landing far too fast in their slippery ship and would pull off all the power. Bad idea. It took as long as 14 seconds for a J33 engine to spool back up and provide useful thrust, and often that was too late.

Another bad idea was that new jet pilots would frantically firewall the power lever when they found themselves on the back side of the power curve with an unresponsive engine. Early J33s couldn’t take the rush of fuel and either flooded or caught fire.

It was also a time before the concept of density altitude was fully understood—that air got thinner and less supportive the hotter and higher it became. Many a P-80 ran out of runway before its wings were ready to lift. By the time the P-80 was little over 2½ years old and still in limited production, 61 of them had been involved in accidents.

Lockheed realized that it needed a jet trainer, which it created by lengthening a standard P-80 airframe by 4 feet 6 inches, making room for a back-seat instructor pilot. Thus was born Lockheed’s most successful jet of all time, the T-33 “T-bird.” Lockheed built well over three times as may T-birds as it did Shooting Stars, and they went on to train, according to some estimates, a quarter million new jet pilots.

Some Lockheed fans insist the P-80 served in World War II. One well-regarded aviation historian maintains that 30-odd P-80As were sent to the Philippines in the summer of 1945 to fly in the invasion of Japan but were grounded for a month because somebody forgot to include their batteries and tip tanks. The anecdote is true except for the fact that it happened in 1946, a year after the war ended. Others have claimed that four P-80s were seen on Saipan during the final weeks of the war, though there is no evidence of this.

Recommended for you

What did happen, however, is that two P-80s were sent to England and two to Italy during the final weeks of the war in Europe. The former two were quickly lost to accidents and there is little evidence of the airplanes in Italy having flown any combat missions, despite much theorizing that the two often went steaming off in search of Me-262s. Some say they were sent to Italy specifically to shoot down marauding Arado Ar-234 high-altitude reconnaissance jets. In fact, the deployment was a simple test of the USAAF’s capability to maintain and operate the jets under combat conditions, and they were never put in harm’s way.

The P-80 may not have contributed to WWII, but it quickly became an effective PR tool soon thereafter. A flight of three made a record-breaking transcontinental crossing in January 1946—the first-ever in jets—and in August of that year Shooting Stars won the Bendix Trophy, jet-class Thompson Trophy and Weatherhead Jet Speed Dash Trophy at the National Air Races. In 1947 the Bendix and jet Thompson trophies again went to P-80s.

That year also saw a modified P-80R called Racey set a world absolute speed record of 623.7 mph. (It lasted only two months, until a Douglas D-558-1 Skystreak upped the top speed to almost 641 mph.)

In 1950 the F-80C made its bones when it went to war in Korea. By that time, the 900 Shooting Stars in the Air Force inventory constituted roughly half of America’s fighter force, and many WWII piston-engine fighters had been relegated to National Guard and Reserve squadrons.

War-weary P-51Ds had to be hastily recalled to service, however, when F-80Cs turned out to be too fast to maneuver with the piston-engine Soviet Lavochkins and Yaks the North Koreans were flying. Still, F-80s on the second day of the war shot down four Ilyushin Il-10s—single-engine ground-attack aircraft that were improved versions of the WWII Il-2 Sturmovik—in what were the USAF’s first jet victories.

Four months later, on January 1, 1950, F-80Cs from the 51st Fighter Interceptor Wing engaged three Soviet-flown MiG-15s in the world’s first jet-versus-jet combat. Lieutenant Semyon Khominich claimed one of the F-80s, killing 1st Lt. Frank Van Sickle Jr., but the Air Force insisted his Shooting Star had been hit by flak, not a MiG. A week later F-80C pilot 1st Lt. Russell Brown scored hits on a MiG-15 and claimed a victory, though years later it was determined that the Soviet MiG pilot had made it back to base.

In any case, the MiG was almost 100 mph faster than the Lockheed. Largely because of this, the F-80 was relegated to a ground-attack role, leaving MiG-bashing to the newly arrived North American F-86 Sabre.

Four F-80C fighter groups were based in Japan and the commute to Korea left them with little fuel to fly useful missions. The solution was “Misawa tanks,” which were essentially faired barrels welded up by technicians at Misawa Air Base, in northern Japan. The largest Misawa tanks held 265 gallons. Early ones, however, lacked internal anti-slosh baffles. During steep run-ins against ground targets, partial fuel in a Misawa tank would flow forward and on the pullout would slosh rapidly aft. This caused at least one fatal accident when the overstressed tank tore off an F-80C’s wingtip and then took out a horizontal stabilizer.

Another try at lengthening the F-80’s short legs was the world’s first in-combat aerial refueling, on July 6, 1951, when three RF-80As gassed up from a Boeing KB-29 tanker over the Sea of Japan. This effectively doubled the reconnaissance planes’ range. The receiving probes for the tanker’s drogue protruded from the nose of each tip tank, however, and the refueling procedure proved too lengthy and cumbersome to adopt operationally.

F-80s flew almost 100,000 sorties during the Korean War and were credited with shooting down 37 North Korean aircraft. But in return 14 Shooting Stars were lost to aerial combat, 113 to anti-aircraft fire, 150 to accidents and 16 to unknown causes. Total losses were equal to 35 percent of all the F-80Cs manufactured. This was well over double the loss rate during the Vietnam War for F-4 Phantoms, then the most vulnerable fixed-wing aircraft of any combatant nation.

By the mid-1950s, Shooting Stars were antiquated enough that they were being sent to South America as part of the Military Assistance Program for members of the Organization of American States. F-80Cs went to Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Uruguay to replace P-47s. Only Peru ever used one in anger, to make low next-time-I’ll-shoot passes over a local garrison that had mutinied.

Some of the last active F-80s were the six used by the FAA, with civil registration numbers, for high-altitude navaid inspections during the 1960s. Today, not a single P/F-80 remains flyable, even among a warbird community that has shown the tenacity to restore some of the oddest and most complex of military airplanes to flight.

I have my own tiny place in Shooting Star history. In July 1948, my grandfather took me to the opening-day airshow at New York’s new Idlewild Airport, which would eventually become JFK. President Harry Truman also attended, to give the opening address, and he was accompanied by a three-ship of F-80s in his flight from Baltimore aboard the Air Force One of the day, a DC-6 that he’d named The Independence. Before his speech the next day, the F-80s flew a low pass over the VIP bleachers—low enough that they blew off Truman’s trademark fedora. It made the front page of many a newspaper.

Lost in the crowd, I didn’t see it happen. But like Forrest Gump, I was there.

Contributing editor Stephan Wilkinson suggests for further reading: Shooting Star, T-Bird & Starfire: A Famous Lockheed Family, by Lt. Col. Rhodes Arnold; Lockheed P-80/F-80 Shooting Star: A Photo Chronicle, by David R. McLaren; and F-80 Shooting Star Units Over Korea, by Warren Thompson.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2022 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe today!

Ready to add an early P-80A to your collection of early jet fighters? Check out our exclusive online modeling column!