A tense interaction between green soldiers and agitated civilians results in murder

One summer Sunday afternoon on the north bank of the Potomac River at Point of Rocks, Md., a group of eight to 10 men had been enjoying the town’s watering holes. Between 5 and 6 o’clock in the afternoon, they commandeered a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad handcar and began laboriously cranking their way north along a portion of the railroad that ran to Frederick and that passed by their homes near Adamstown, about six miles north of Point of Rocks.

It was likely a familiar outing for the men. Take a day to go have a few drinks at the end of the week, and then head home and get ready for the Monday workday. But things were far from ordinary in southern Frederick County on July 21, 1861. The First Battle of Bull Run was raging in Manassas, Va., some 40 miles to the south, signaling the true beginning of an American bloodbath. And for the past month, Union regiments had been marching into Maryland’s Potomac River bottomlands. One of those regiments was the three-month 1st New Hampshire Infantry, which had been formed in May and was in a brigade commanded by Colonel Charles P. Stone.

The 1st was in the 7th Brigade of the Department of Pennsylvania, commanded by Maj. Gen. Robert Patterson, hastily formed to protect Pennsylvania, Delaware, and Maryland. Sources differ as to who the 1st was brigaded with, but in the Official Records and in the regiment’s 1890s history, The First Regiment New Hampshire Volunteers in the Great Rebellion, it appears the New Englanders were sent with the 9th New York, the 1st Pennsylvania, elements of the District of Columbia Volunteers, some cavalry and an artillery battery to keep an eye on the railroad line, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, and important river crossings such as Point of Rocks.

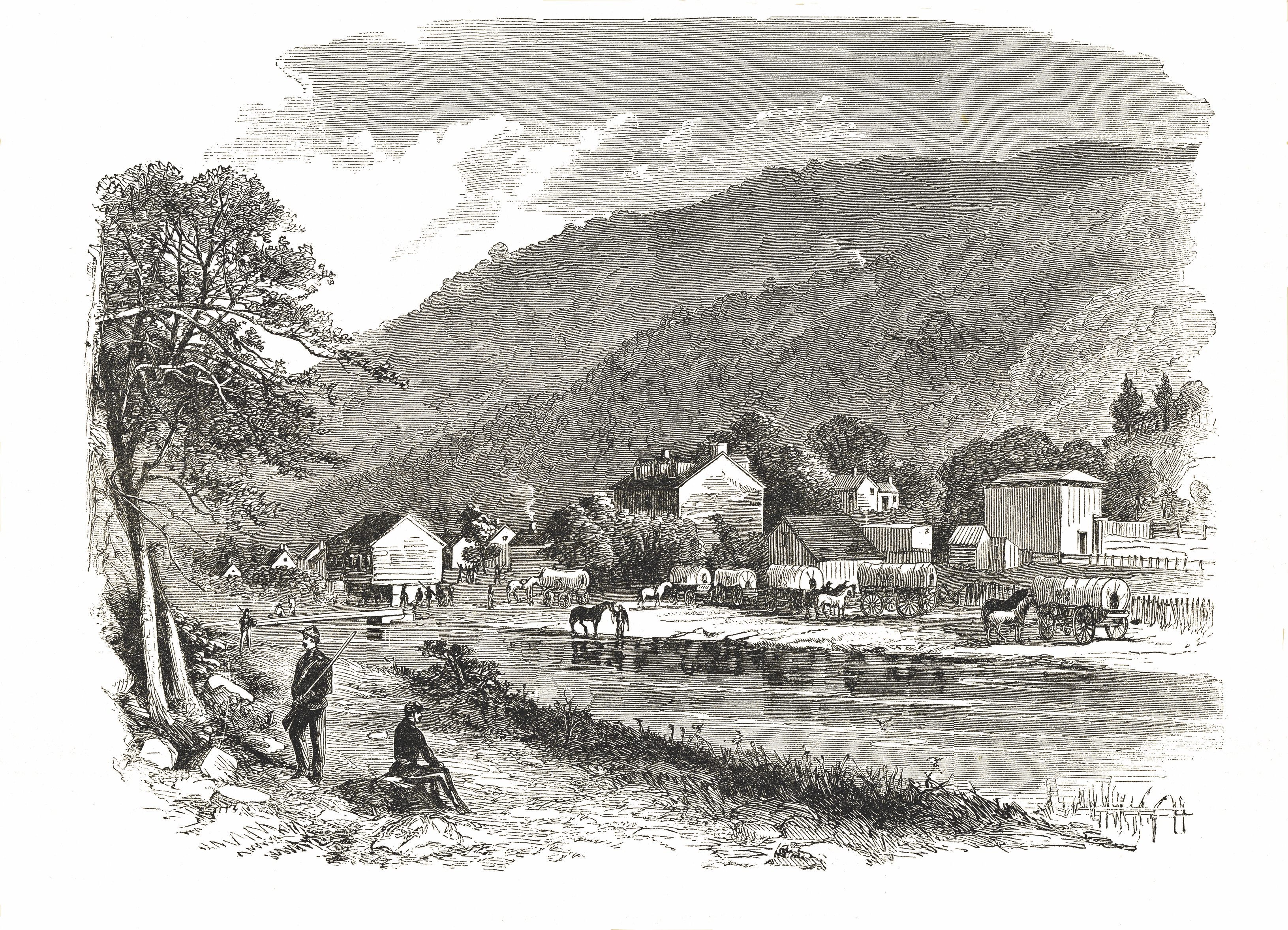

To that end, the 1st had been marching back and forth from Rockville to Harpers Ferry, leaving detachments scattered along the riverbank at important locations. The majority of their contact with Confederates had consisted of taunting rival pickets across the Potomac. By late July, some of the New Hampshiremen had established “Camp Berry” at Point of Rocks, where Confederates already razed the covered bridge across the river on June 14. Regimental history author Stephen Abbot, the 1st New Hampshire’s wartime chaplain, described the town as a “dirty secesh village,” and recounted how Colonel Stone was refused “entertainment” at Point of Rocks’ St. Cloud Hotel. Stone got a company of troops to take over the hotel and help him “run it on his own account.” The dismissive treatment of the Union troops reflected the Southern sympathies found in Point of Rocks, and much of southern Frederick County. After all, the bluffs of Loudoun County, Va., were clearly visible just across the river.

The men of the 1st New Hampshire were far from home and surrounded by a populace that did not welcome them. So when that handcar full of Sunday revelers headed home from the bars of Point of Rocks and ran into a picket line of the 1st New Hampshire, tension quickly grew. The soldiers stopped the car, a confrontation between soldier and civilian ensued, and Private Samuel Webster shot dead a teenage Maryland resident named Samuel Calvin Lamar. Lieutenant William F. Greeley of the 1st was in charge of the detail along the railroad, and he quickly arrived and placed Webster under arrest. Greeley collected the following statements by four of the civilians on the handcar to try and make sense of the incident. Spelling and punctuation have been maintained as written. Biographical information has been added for the civilians when it is known.

Statement of John P. Crown

Age 22, Occupation, Printer

Was on the handcar going down on the way to Adamstown when the soldiers were approaching. One of them ordered us to halt and said we were under his command. It was suggested by someone on the car that some of us should get off while the rest should take the soldiers to camp. There was much talking, some suggested one thing, some another. Mr. Collins who had charge of the car asked all to get off the car, which was done with the exception of Calvin Lamar, and George Brady [Bready]. Mr. Brady told the soldiers he could take them anywhere they wished to go. The man who was shot said the same. The soldier who shot Lamar told him that he was under his orders and that he must obey him or he would shoot him, and then presented a pistol at his head. The man who was shot said I am not under your orders, fire away. I remonstrated with Lamar and told him not to say anything. The soldier told him he did not want to shoot him. Some of the persons who were on the car started towards Adamstown when the soldiers turned around and bade them halt. After he had said this the soldier pointed his pistol at Lamar when Lamar said he was not afraid of him. The soldier then fired and Lamar fell on the left side of the car. I then said that we must take the car down to camp and get a surgeon, when the soldier said let the son of a bitch die. I shot him and remarked I was not to blame as he did not obey my orders and then told the men to take him down to the camp. Previous to his shooting Lamar the soldier pointed his pistol at all of us and fired at a man named Thomas Harwood and missed him. The soldier who shot Lamar was drunk. I think that Lamar was drunk also.

Statement of Curtis Wheeler

Was with the party who had the handcar. Saw two soldiers on the track. One of them ordered us to halt which we did. Someone on the car asked the soldier where he was going. He said to the camp. We told him to get on and we would take him anywhere he wished to go. The soldier caught hold of the car as it started and told us to halt. We stopped as soon as we could. Lamar told the soldier to get on if he was going, when the soldier told him to wait til he was ready and said the car was under his orders and if he did not obey him he would shoot him. Lamar made a reply which I did not hear. The soldier then drew his revolver upon which Lamar said shoot and be damned. The soldier said I do not want to shoot you. There was some talking among the men and boys who were with the car and the soldier pointed his revolver at one of the men, Thomas Harwood. One of the men spoke when the soldier told him to shut up. Harwood went toward the soldier and the soldier moved his pistol and fired without taking aim at anyone. The ball I think went in the ground. There was some talk again between Lamar and the soldier when the soldier fired at Lamar and he fell. Think that the soldier was drunk. Lamar drank during the two hours before we saw the soldiers. Three times of whiskey and two of beer. We all drank several times of whiskey and beer before we saw the soldiers.

Point of Rocks Md. Sunday July 21, 1861 7 o’clock P.m.

Statement of Charles E. Bready

Adamstown Resident,

Age 17, Occupation, Farmer

I left Point of Rocks Sunday afternoon about five to six o’clock with a party of some eight or ten men on a handcar to go to Adamstown. We had been to Pt. of Rocks on a pleasure excursion and had drank liquor a number of times while there. We had got as far as the curve in the road about a quarter of a mile from camp when we met a party of soldiers & men coming towards us. One of the soldiers ordered us to halt! We stopped the car. The soldier said he wanted us to return to camp with him & his party. We told him we would take them back, and some of our men on the car jumped off to make room for them. My brother, myself & two others remained on the car to bring them up. One of the soldiers got on the car when we started it for the camp, moving slowly for the others to get on also. The soldier who had not got on the car ordered us again to halt. We halted. Lamar said get on. The soldier told Lamar to hold his mouth or he would shoot him. Lamar said shoot and be damned, you can’t scare me. The soldier drew his pistol and fired on him. Lamar fell to the ground.

When the men jumped off the car to make room for the soldiers’ party, the man who shot Lamar ordered them to stand, using language which I do not now remember and drew his pistol and fired at a man named Thos. Howard [Harwood], the bullet entering the ground near Howard’s feet. I think the soldier that shot Lamar was intoxicated. The other soldier was on the car at the time of the shooting. Don’t know if he was standing or sitting.

Can give no account of what was said immediately after the shooting. Can recognize the two soldiers. One of the party with the soldiers also ordered us to halt.

Statement of George C. Bready

Adamstown Resident,

Age 27, Occupation, Farmer

We started from Pt. of Rocks about 6.00 this afternoon in a handcar to go to Adamstown. There were about ten of us. Had gone about one half mile from here when we were met by a party of two soldiers and four or five citizens.

The soldier ordered [us] to stop and take his party to camp. All of our party got off the car excepting Calvin Lamar & myself. One of the soldiers said he was a Sergeant. He had two stripes on his arm, said we must obey his orders. When the soldier (the Sergeant) ordered us to halt he drew his pistol and threatened to shoot us if we did not obey him. I told him I was ready to obey him. He threatened us again and leveled his pistol, firing at me then at Lamar. Lamar said shoot and be damned. The soldier then fired on Lamar and Lamar fell to the ground. When our men first got off the car the Sergeant threatened to shoot unless they stopped.

After the shooting the soldiers got on the car & we went to the camp with them. Lamar was a farmer and worked for his uncle Jno. B. Thomas. Am satisfied the Sergeant was drunk. Can recognize both of the soldiers. I recognize Chas. S. Davis, Co. B as one of the soldiers. My party all live at Adamstown, had been to Pt. of Rks on a pleasure excursion, had drank there a number of times.

Point of Rocks, Md. Sunday July 21 7 o’clock P.M.

The above statements were made to me by the several parties and committed to writing as stated. Wm. F. Greeley Lieut. Co. E, 1 N.H.V.

[hr]

The Soldiers

Private Samuel Webster

Though some of the men referred to Webster, the soldier who shot Samuel Calvin Lamar, as a “Sergeant,” he was a private during his term of service with the 1st New Hampshire. News of the murder quickly spread throughout the county, and Frederick resident and copious diarist Jacob Engelbrecht noted the incident in his journal on July 22: “Killed—Calvin Lamar…was shot yesterday…near the Point of Rocks by Samuel Webster of Company B, 1st New Hampshire Regiment….” Webster’s service record at the National Archives states that he had been placed “Under arrest and detained by civil authority at Frederick City, MD, since July 22, 1861.”

Webster remained in jail until his trial in November 1861. On the 13th of that month, diarist Engelbrecht penned, “Acquitted—Samuel Webster of the 3 months New Hampshire Volunteers who shot Calvin Lamar on the 21 of July 1861 near the Point of Rocks had his trial yesterday in Frederick County Court & was ‘acquitted’. (‘Not Guilty’). The trial lasted all day & the verdict rendered about 8 o’clock PM For the state, John A. Lynch Esquire. For the prisoner, Colonel William P. Maulsby and Grayson Eichelberger Esquire. Wednesday November 13, 1861 8 o’clock AM”

Webster later served in the 7th New Hampshire Infantry and became a sergeant in that regiment when he was 24 years old. In October 1863, he transferred to the 1st New Hampshire Heavy Artillery, and died of disease in February 1864.

Lieutenant William F. Greeley

After the 1st New Hampshire’s term of enlistment expired in August 1861, Greeley, who was 30 in 1861, joined the Regular Army and served as a lieutenant in the 11th U.S. Infantry. On October 1, 1864, he was shot in the right eye during the Battle of Peebles’ Farm, Va. The bullet struck him a glancing blow, but drove pieces of his skull into his brain. He spent the remainder of the war in hospitals and left the service after Appomattox. He married and raised a family while living in New York City. But his National Archives pension file indicates that the wound troubled him the rest of his life, causing headaches, nerve issues, and sleeplessness.

In January 1879, he walked out of his home on 183 W. 135 St. in Manhattan and never returned to his family. His son, William L. Greeley, wrote in the pension file that although he saw his father from time to time, the elder Greeley never saw his wife, Francis, again, though they did not divorce and the marriage was never annulled. Lieutenant Greeley died in 1914 in Waverly, Mass., and is buried in New Hampshire.

The Civilians

John Crown

An August 1863 Federal draft roll states that Crown was “In the Rebel Army” and 26 years old. He had joined Elijah Viers White’s 35th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, often called “White’s Comanches.” On September 15, 1863, Crown was captured in Loudoun County, and spent the rest of the war imprisoned at Fort McHenry in Baltimore. He took the Oath of Allegiance to the United States in May 1865. The 1870 census lists him living in Frederick.

Curtis Wheeler

No further information has been found about Wheeler.

Charles E. Bready

Charles, the younger of the Bready brothers, also enlisted and served in the 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry. A member of the Alexander Young Camp of the United Confederate Veterans, he died in Frederick County at age 72.

George C. Bready

The elder Bready moved to Baltimore and worked as a railroad conductor after the war.

Thomas Harwood

Harwood did not write a testimonial, but was mentioned in them as another man at which Private Webster shot. Harwood also enlisted in the 35th Battalion Virginia Cavalry, and was captured at the June 9, 1863, Battle of Brandy Station.

The Victim

Samuel Calvin Lamar

Born on September 12, 1842, Samuel Lamar, who seemed to prefer to go by “Calvin,” was 19 years old and working as a merchant when he was killed. He was one of six children of Benoni and Mary Lamar, well-off farmers who owned two slaves. Benoni died in 1858 when he was struck by lightning, and Mary is listed as a single widow on the 1860 census. Samuel’s sister, Annie, would marry Charles E. Bready in 1869.

1st New Hampshire historian Stephen Abbot mentions Lamar’s shooting in the regimental history thusly: At Point of Rocks “occurred the unfortunate conflict, the only one of the kind during the campaign, in which a young Rebel was killed by a pistol shot fired by a soldier named Webster.” It’s worth noting that Lamar is referred to as a “Rebel” by Abbot, although he was clearly a civilian when he was shot.

Less than an hour’s drive south of Point of Rocks, the First Bull Run battlefield is marked with monuments and cannons that commemorate sacrifice and courage on July 21, 1861. The only monument to the alcohol-fueled incident that claimed the life of a teenager, however, is Lamar’s lonely grave recently located in an abandoned cemetery not far from where his murder took place. Standing at his headstone deep in the woods, hidden by briars and brambles and bearing his death date of July 21, 1861, you can hear trains rumble by using tracks that have been in the same location since the 1860s, and on which his murder occurred. It’s impossible to know how much trauma and grief this small, sad incident of the conflict caused. The great writer and eyewitness to our national tragedy, Walt Whitman, put it best: “The real war will never get in the books.”

Dana B. Shoaf is the editor of Civil War Times. He purchased and owns the original testimonials on which this article is based. Some of the additional information about the soldiers and civilians mentioned in the article was obtained from soldier service records and pension files held at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and from the 1860 Census.