President Truman called for stricter safety codes after dozens leaped to their deaths from ‘fireproof” building

The fire started about 3:15 a.m. on Saturday, December 7, 1946. Within the Winecoff Hotel, at 176 Peachtree Street in Atlanta, Georgia, the impressive central stairwell operated like a giant chimney that drew the flames from floor to floor of the 15-story establishment, a prominent fixture of Atlanta’s main thoroughfare. Crews hurried every piece of firefighting equipment available in the city to the scene. The first truck, from a station two blocks south, was reported in position within 30 seconds of receiving the alarm. Eventually 385 firefighters, 22 engine companies, and 11 ladder trucks arrived.

But the call to the fire department was not made until 3:42—a good 20 minutes after the conflagration, which had started in a mattress stored in the hall outside Room 326, had gone out of control.

Feeding on wooden doors and burlap covering in hallways, flames reached the 11th floor. An internal alarm, which had to be triggered by hand at the Winecoff’s front desk, did not sound until around 3:30. By then the building was filled with screams for help.

The Winecoff had a steel structure clad with stone on the lower three and upper two floors and with brick on the intervening floors. Structural clay tile behind the exterior facing was supposed to make the building fireproof, although there were no sprinklers or fire escapes and the hotel’s interiors included highly flammable materials. The Atlanta fire code, which dated to 1911, required multiple staircases in high public buildings, but that rule contained an exception for buildings with a footprint of less than 5,000 square feet. The Winecoff had been squeezed into a tiny lot atop one of the city’s highest hills, and so measured only 4,386 square feet per floor. That meant the hotel legally could have only a single staircase—an imposing design feature that swept from floor to floor.

That Friday night the 194-room hotel had 285 guests registered; the final death toll was 119. Another 65 people were injured. The Winecoff blaze—still ranked as the worst hotel fire in United States history—remains memorable not only for its rapacity but for its influence in the development of nationwide fire safety codes.

His days in combat during World War II still fresh in his mind, hotel guest Major General Paul W. Baade said that for sheer terror that night in Atlanta outdid leading the U.S. Army’s 35th Division onto Omaha Beach on D-Day. “At least you felt you had a chance in dodging bullets,” the general said upon being rescued from the Winecoff. “But you’re just helpless when you are trapped in a hotel room with roaring flames all around you.” Baade and his wife, Margaret, woke in their sixth-floor room around 3:30 a.m. when they heard shouting. Cracking the hallway door and seeing only flames, he realized they could not get out that way. The couple waited until firemen pulled them through a window.

Waiting wasn’t an option when flames invaded rooms, as often occurred. To survive, brothers Eves and Robert Muns, plumbers from Augusta, shinnied down the front wall of the Winecoff using bedsheets they knotted together. By the time Robert and Corrine Bault of Murphy, North Carolina, woke, their 14th floor room was afire. Opening a window, Robert stretched to extend a sheet to the room next door and, as hundreds of spectators watched, he and Corrine, clutching the sheet, edged along a cornice to what they hoped was safety. The second room’s occupants, Mr. and Mrs. J.B. Phillips of Lithonia, Georgia, had barricaded the wooden hallway door using mattresses sopping with water they fetched from the bathroom. The quartet kept up a two-and-a-half-hour bucket brigade until firefighters quelled the flames.

A substantial number of individuals on lower floors climbed down firefighters’ ladders or jumped successfully into nets strung on metal frames being held by teams of firefighters. Though flames did not reach the uppermost floors, smoke did, killing many. Occupants of middle-floor rooms had few options; firemen’s ladders reached no higher than the seventh story.

Dr. Robert Cox, also of Murphy, North Carolina, was with his family in a 10th-floor room. Trapped by smoke and flames, three-year-old son in his arms, he leaped, hoping to reach a rescue net. Realizing in midair that he was off-target, the father tossed his son, Bob, at the circle of safety. Cox’s head struck the net’s frame; he died of his injuries. Little Bob landed safely, grew up to be a doctor himself, and told the story at a 70th anniversary gathering of Winecoff fire survivors, their descendants, and victims’ relatives.

Former GI James D. Cahill, visiting in Atlanta to complete paperwork to reenter Georgia Tech, fled the hotel on foot—then realized his mother, in a sixth-floor room, was trapped. At the adjacent Mortgage Guaranty Building, separated from the Winecoff by a 10-foot alley, Cahill found a board long enough to reach his mother’s window and sturdy enough that she could crawl to safety 60 feet up. Firemen followed Cahill’s lead, extending ladders across the alley and guiding occupants out of room after room. The Mortgage Guaranty building was 12 stories high. The nearness of its roof tempted desperate Winecoff guests. Those who misjudged the 10-foot gap fell to their deaths. Dorothy Moen, 16, made the leap from her 7th floor room. She broke her left arm and right femur and knocked out 13 teeth—but she survived, constrained at Grady Hospital in a waist-down cast.

Driven by flames, some guests simply jumped, some dying, some surviving. One surviving jumper appeared in a lone image that seared the Winecoff fire into the minds of Americans. Physics graduate student and amateur photographer Arnold Hardy, 24, had been returning from a party when he heard sirens. He called the fire department, learned that the Winecoff was burning, and got to the street outside. With his 2¼ x 3¼ Speed Graphic’s aperture at f4.5 and his shutter at 1/400th of a second, Hardy had used up four of five flashbulbs when he heard a shriek. He turned and framed 41-year-old Daisy McCumber airborne over Peachtree Street as she passed the hotel’s third floor. The Georgia Tech student’s photo, which he sold to the Associated Press for $300, received the Pulitzer Prize for photography the following year.

McCumber lived, but before hitting the ground she struck a pipe and a railing. She underwent seven surgeries to repair her fractured back, pelvis, and legs, living to 86 and staunchly resisting attempts to spotlight her as the woman in Hardy’s much-reproduced image of her with her skirt above her waist and her bloomers on display. Hardy died in 2007; his funeral was held the afternoon of December 7, the 61st anniversary of the fire.

Winecoff guests that night included 52 of Georgia’s brightest high school students, including Moen, one of 325 teens in the capital for a YMCA assembly. Of those at the Winecoff, 22 survived. The fire also claimed the hotel’s builder, W.F. Winecoff and wife Grace, both 76. The Winecoffs, who had sold the hotel in the 1930s, lived there in a top-floor apartment they had occupied since the hotel’s earliest days.

Of the Winecoff fire’s 119 deaths, doctors traced 48 to burns, 40 to asphyxiation from smoke, and 31 to injuries sustained jumping or falling. That night the wind had been from the north, so rooms in the hotel’s southern side got much more smoke than those facing northward. No logic seemed to explain a peculiar room-by-room pattern of death and survival until someone observed that guests who opened the transoms above their hallway doors to let air circulate inadvertently provided a path for flames.

Two days after the tragedy, Atlanta fire marshal Harry Phillips told the City Council that the fire’s cause likely would never be established definitively—a prediction that has held; the cause remains in dispute. Phillips posited the most likely cause as a lit cigarette flipped, probably by an inebriated guest, onto that mattress in the third-floor hallway. The U.S. Fire Administration says that a mattress fire doubles every minute. Mattress fire-retardant standards now in force were not adopted until the 1970s.

The burning mattress theory became the official explanation, but doubts persist. Hamilton Lokey Sr., who represented the hotel’s insurer in suits filed by survivors and families of the deceased, blamed arson, an analysis that had a long life. In 1993, former Atlanta Journal and Constitution reporter Sam Heys published a book on the Winecoff fire in which he pointed a finger at Andrew McCullough, a former convict who according to this theory was in a poker game at the hotel, left, set the fire, and returned to the game. However, when the Heys book came out Constitution reporter Keeler McCartney, who had covered the fire, said that he

had heard the story about the guy who left a card game and set the fire. McCartney wrote about the rumor in the days after the blaze, “but I could never nail it down, and neither could the police,” he said.

Immediately after a 2016 fire in an Oakland, California, performance space killed 30 persons, James Pauley, president of the National Fire Protection Association, said, “When a deadly fire happens, it is usually because something isn’t followed or something goes wrong or we learn something new.” Accident or arson, the Winecoff fire did teach America something new and led to a major rethinking of fire safety codes.

Many killer fires have stemmed from malfeasance. The December 30, 1903, Iroquois Theatre fire in Chicago, which took at least 602 lives, still ranks as the nation’s deadliest single-building fire. Chicago authorities had allowed the facility to open the month before despite blatant violations of the city fire safety code, including the absence of sprinklers, alarms, water connections, and mandatory separate staircases to two upper levels. The 146 deaths in the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in Manhattan’s Asch Building could be attributed largely to the factory owner locking exit doors to keep workers from taking unauthorized breaks. Severe overcrowding figured in the 1942 fire at Boston’s Cocoanut Grove nightclub and its 492 deaths; legal occupancy was capped at 460, but the owners had allowed more than 1,000 clubgoers to cram the place that Saturday after Thanksgiving. When a fire started, exits could not handle the crush.

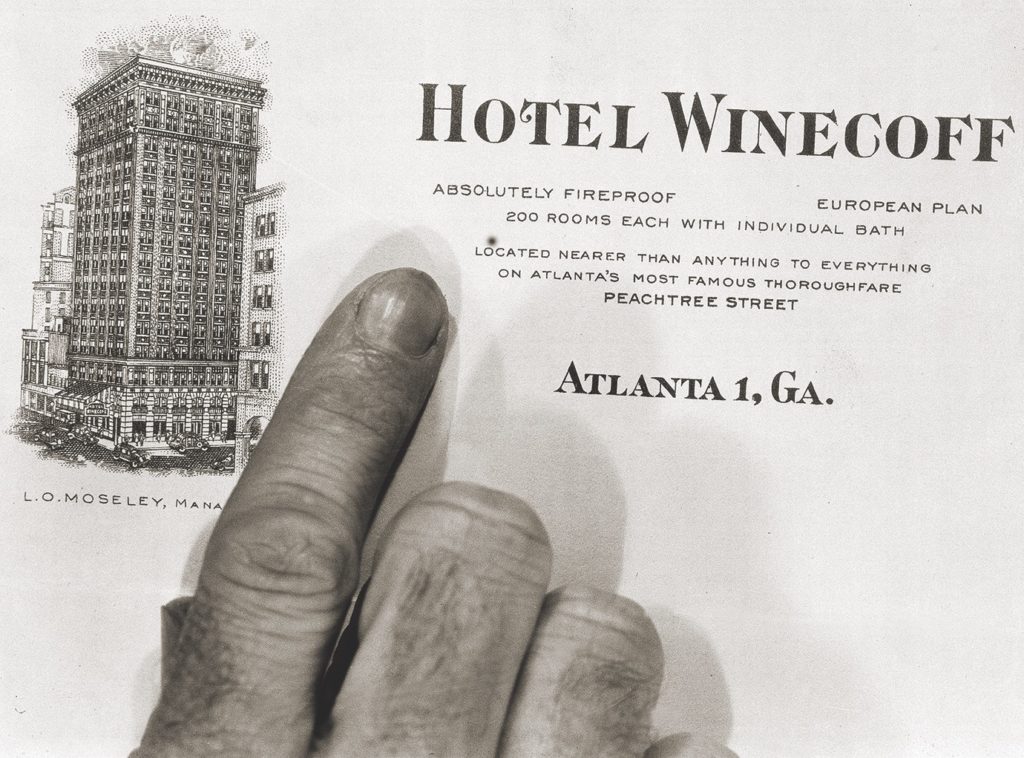

the hotel was “absolutely fireproof.” (AP Photo)

The Winecoff’s management was not in that nefarious league. News stories of the day pointed out that the hotel lacked both fire escapes and sprinklers. But the building—widely advertised as fireproof—complied with applicable regulations of the pre-World War I era in which it was built. By 1946 standards, the hotel deserved a rating of “fire-resistant,” fire marshal Phillips said. And Atlanta’s chief building inspector, Marvin Harper, told the City Council that his office had done everything possible under existing regulations to make the building safe. Analyzing the fire’s progression, the Building Officials Conference of America issued a report in March 1947 that said that while in some situations exterior fire escapes can provide rescue, “it is questionable whether they would have furnished a safe means of egress in the Winecoff Hotel fire, where intense and simultaneous belching of fire from practically all windows on the floors above the third would have vitiated their usefulness.”

The villains in the Winecoff fire were society and the prevailing definition of “fireproof.” The fire codes embedded in city building regulations in large part had been shaped by property insurers, whose primary concern was the preservation of buildings because that is what their policies covered. While lawmakers looked to these standards as models, the original drafters had builders in mind. Owners of buildings that did not conform to insurers’ standards would have trouble getting policies to protect them against fire loss or at least would have to pay higher premiums for those policies. That needed to change. A week after the Winecoff fire, H.N. Pye, chief engineer for the South-Eastern Underwriters Association, warned insurers by letter that “even though a building may be of non-combustible construction, the contents, decorative material and furnishings may produce a fire of serious magnitude as to flame and which will quickly fill the hallways with toxic gases of combustion.”

The problem reached far beyond hotels. A tally of annual deaths from fires less spectacular than hotel blazes neared 10,000. Fire losses in the United States for 1946 totaled a record $560 million, not counting tens of millions of dollars’ worth of timber lost to forest fires. Washington state expected to lose $750 million that year.

The first American fire codes date to 1631, when Massachusetts Bay Colony Governor John Winthrop outlawed wooden chimneys and thatched roofs on houses in Boston. Flaming disasters bred stricter rules. As early as 1815, New York City was banning new wood frame construction in parts of that city and requiring metal doors on warehouses. After an 1871 fire destroyed a third of the buildings in Chicago, officials in that city limited the types of materials that could be used in reconstruction and demanded more space between buildings. Boston similarly tightened its building code and inspection regime after an 1872 fire destroyed 60 acres of buildings.

Front page of the Los Angeles Times the day after the Coconut Grove Club fire in Boston, Massachusetts, when the final death toll of 492 was not yet known. (Granger NYC)

But those codes were local. The concept of measuring fire prevention efforts against a uniform national standard originated with the National Fire Protection Association. Founded in 1896 by 20 fire insurance organizations, this trade group initially admitted no other member companies. The 20 had joined forces over a pressing problem: automatic sprinkler systems. Such systems existed, but lack of standardization was keeping them from providing the expected protection. A tangle of varied standards for piping size and sprinkler spacing rendered system performance inconsistent and unreliable. The insurers association developed uniform standards and lobbied for their adoption.

Through the 20th century the concept of fire safety standards spread beyond sprinkler standardization as authorities learned more—often through headline-making tragedies—about what made fires rage and how better to control them. The 1903 Iroquois fire led cities and towns to require sprinkler systems in buildings where many persons gathered. In 1904, fire destroyed 2,500 buildings in Baltimore despite the arrival of fire companies from Washington, DC, Philadelphia, and New York. Baltimore hydrants did not fit the visiting firemen’s hose couplings; the massive consequences of that problem resulted in widespread adoption of a standard coupling. The Cocoanut Grove fire led to requirements that decorations in public buildings be noncombustible.

Built at a time when the focus was on preserving a building’s structural integrity, the Winecoff measured up to that mark. Even substantially gutted, the hotel’s brick-and-masonry exterior stood firm after the fire, and the renovated structure is doing business today as the Ellis Hotel, a four-star property listed in the 2016 Condé Nast Traveler Gold List of the world’s best places to stay.

But until the Winecoff burned, developers of fire codes gave occupant safety at best secondary attention. The Winecoff fire changed that. Horrific as that blaze was, its emotional impact on America was amplified by the fact that it did not stand alone in 1946. In the month of June alone that year, 61 persons had died in a fire at Chicago’s La Salle Hotel; 19 in Dubuque, Iowa, when the Canfield Hotel caught fire; and 10 in Dallas, Texas, when the Baker Hotel burned. In July 1946, a blaze at the Herbert Hotel in San Francisco killed four firefighters. A day after the Winecoff went up, 11 people died in the Barry Hotel conflagration in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. A survivor explained that he got out of the Barry alive because he had just read a news report about the Winecoff saying that many victims would have lived had they just stayed in their rooms until firefighters controlled the flames, advice he took to heart.

The Atlanta toll and attendant coverage stirred demands for action. The Winecoff catastrophe, The New York Times said, “may bring reforms we should have had long ago. If its tragic meaning stirs the heart of this nation as it should, our people will see that hotel dwellers shall no longer be exposed to needless hazards.”

Among those whose hearts were stirred was President Harry S. Truman. Less than a month after the Winecoff fire, Truman declared he would convene a National Conference on Fire Prevention. That three-day Washington parley drew around 2,000 delegates from across the country—a first-ever meeting on fire safety bringing together industry figures and personnel from federal, state, and local government agencies. “We have a complexity of building laws and codes in some communities, and too few in others,” Truman told delegates. “In many communities, those laws are outdated and the responsibility for safety from fire is not clearly defined.” A 1945 National Bureau of Standards study had examined regulations in 3,322 municipalities, finding that 1,342 had no building code at all and that of the rest two-thirds were relying on rules not updated for at least ten years.

Publicity surrounding the Truman conclave added impetus to safety concerns already vivid in the wake of the Winecoff disaster. Some states decided they no longer could leave fire safety to individual municipalities. Within months of the Atlanta fire, Indiana had passed its first statewide fire safety code. Georgia passed a building exit code, requiring new structures to have multiple means of egress.

Regulations implementing the Georgia law took effect on the first anniversary of the Winecoff fire. Before World War II, only Maryland, Illinois, and Oklahoma had required that firemen undergo formal training; the 1946 hotel fires and the national fire prevention conference spurred Pennsylvania to join that list in 1947 and Maine in 1948.

Even without state legislatures’ prodding, municipalities acted individually. Many amended codes for the first time to insist that public buildings have sprinkler systems, that hotels install fire doors capable of sealing off corridors, and that facilities have multiple staircases. No longer could guest rooms have over-door transoms. Regulators began demanding that inside each guestroom door hotels post a map of that floor of the building clearly marked with routes to the safest exit.

Tougher standards written into the codes specified which materials builders could use in hotel construction. Incorporating wartime research into flammability, these provisions recognized the importance of three characteristics: how a material contributed to the spread of flames, how quickly a material itself became fuel, and how much noxious smoke a material emitted when burned.

Significantly, regulators began to develop new confidence in their standing to order retrofitting of vintage hotels like the Winecoff, an inclincation until then thwarted by the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibits the taking of private property for public use without just compensation. Regulators had feared that forcing owners to spend heavily to bring older buildings into line with new fire safety standards would bring accusations of unconstitutional “taking.” That reluctance faded amid a string of zoning decisions in which the Supreme Court allowed new restrictions on existing buildings provided the rules were in the public interest. By the late 1940s, authorities nationwide were beginning to enforce new fire safety standards not restricted to new construction.

In 1994, the city of Atlanta installed at the corner of Peachtree and Ellis a historic marker “dedicated to the victims, the survivors, and the firemen who fought the Winecoff fire.”

But perhaps the more important monument to those victims is the fact that safety code improvements those deaths spurred have meant that to this day no worse fire has occurred in the United States and that the nearest contender—a 2003 fire at the Station nightclub in West Warwick, Rhode Island, in which 100 perished—is the only fire since the Winecoff whose toll has reached three figures.

This story appeared in the June 2020 issue of American History.