On March 15, 1943, the Japanese destroyer Akikaze anchored at Kairiru Island, just off the northeast coast of New Guinea. A landing party went ashore and soon returned with a German Catholic bishop, a few dozen priests and nuns, a female servant and two orphans. Akikaze then sailed northeast to Manus Island, where two days later it picked up a score of German Protestant missionaries and civilians. While the Japanese sailors were standoffish with their reluctant passengers, they did not mistreat anyone. Within hours, however, all

of the civilians—men, women and children alike—would be killed, their bodies thrown overboard.

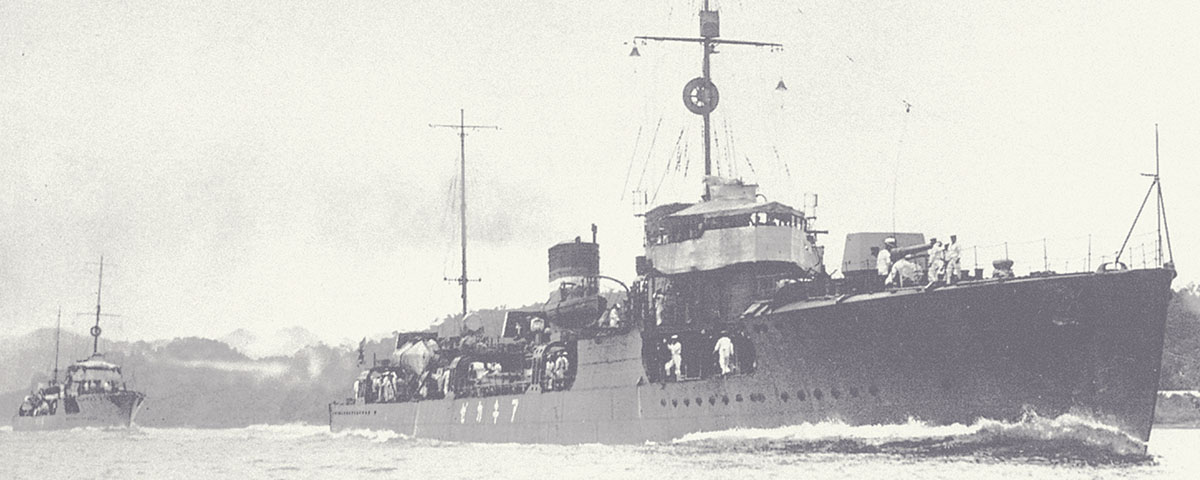

his people were one and indivisible. (National Diet Library)

During World War II Japanese troops commanded the grudging respect of Allied forces as fighting men but were widely condemned for their barbaric treatment of civilians and prisoners of war. The citizens of neutral nations, and even some of those in league with Japan, suffered badly at the hands of imperial authorities, who responded to any perceived threat with extreme violence. The well-recorded atrocities stemmed from Tokyo’s harsh treatment of its own troops, which shaped their training and mind-set even before the outbreak of war.

In 1931, under the administration of Prime Minister Inukai Tsuyoshi, Lt. Gen. Sadao Araki was appointed minister of war, a cabinet position that gave him widespread influence and enabled him to spread his own brand of radicalism within the military establishment. Araki was the author of Kodoha (the “Imperial Way”), a political philosophy that promoted totalitarian rule, militarism and expansion. He also strongly advocated the concept of seishin kyoiku—spiritual training of Japanese troops based loosely on the centuries-old samurai warrior code. Araki was forced to retire in the wake of a failed coup in 1936, but two years later he was appointed education minister, a position affording him access through the national education system to infuse his beliefs into schools.

According to the tenets of the Imperial Way, the emperor and his people were one and indivisible. The army was to be the vanguard of this new order, which aimed to build a nation dedicated to denial of self in favor of the collective whole. It demanded such ardent loyalty that citizens would feel privileged to die for the emperor.

The ultimate goal was to instill a nationwide militaristic spirit. From the day a recruit entered the barracks, the army would become his “father and mother,” and commanders firmly believed that self-discipline and willpower could overcome all obstacles. Bushido—the collective spirit and ideals of the samurai way of life—became the national code of ethics, the samurai sword a national symbol of the Japanese mystique.

From early childhood citizens were taught their emperor was the godlike spiritual head of the nation, both divine and absolute. Schoolchildren were taught to recite a verse from an imperial rescript handed down by Emperor Meiji during his 1867–1912 reign: “Whether I float as a corpse under the waters, or sink beneath the grasses of the mountainside, I willingly die for the emperor.”

Each morning during their two-year training period, with the rising of the sun, Japanese soldiers also recited that verse. Trainees were taught to be fierce and hardy, to relish close combat and to always be on the attack. If one were wounded, he would be of no use to the emperor and thus disgraced. Surrender under any circumstances meant dishonor; death was expected. The Senjinkun, a Japanese field army service code issued to soldiers in 1941, drove home that expectation: “You shall not undergo the shame of being taken alive. You shall not bequeath a sullied name. After exerting all your powers, spiritually and physically, calmly face death, rejoicing in the eternal cause for which you strive.”

The only way one could achieve the “eternal cause” was either to be victorious or to die. To be captured alive was to be regarded as an outcast. At war’s end there would be no welcome for those who had been taken prisoner. Soldiers were led to believe their families and even their home villages would refuse to take them back. In all instances they were expendable in the service of the emperor.

The recruits marched for miles in the summer heat without helmets, and when they were completely exhausted, their officers would order them to march double-time before running the last mile. In winter the men trained in the cold and bivouacked without tents in subzero weather, often in the snow. During maneuvers officers often required them to stay awake for three or four days. As part of the indoctrination process, officers routinely slapped, punched or kicked recruits to ensure they would obey orders without question or hesitation.

Recruits were told that death on the battlefield would instantly make them kami, venerated Shinto deities, who would join their guardian spirits at the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. If any man died during training, his body was cremated and his personal effects (including locks of hair and nail clippings) were sent to the family with a note reassuring them their son had died a hero’s death for them and their emperor. The expression “cult of death” perhaps best captures the imperial military’s quasi-religious mind-set.

Although many of the Imperial Japanese Army’s cruel and barbaric acts were recorded for posterity, their counterparts in the Imperial Japanese Navy sometimes took brutality to whole other level. Although initially trained in the traditions and tactics of the Royal Navy, the Japanese navy lacked one key component of the British ethos—the practice of extending compassion toward those whose ships had been sunk or rendered helpless. The Japanese were simply uninterested in such a concept, considering it alien and not reflective of their society and military culture.

One Japanese military doctor captured by the Americans, in describing the difference between Western and Japanese philosophy, explained that the former told a person how to live, the latter how to die. That attitude not only drove millions of Japanese to their deaths, but also cost the lives of thousands of Allied POWs and civilians.

In 1943 many Roman Catholic and Protestant priests and nuns from Germany were living on New Guinea, an existence disconnected from and largely unaffected by the war raging in Europe or even in the Pacific. Such missionaries fell under the legal protection of the Nazi regime, and Germany and Japan had been allied since signing the September 1940 Tripartite Pact with Italy that established the Axis powers. The Roman Catholic priests and nuns also came under the protective umbrella of the Vatican, a neutral nation.

The Vicariate of Central New Guinea, based in East Sepik province, operated across the Wewak hinterland and along the remote Sepik River. Then headed by Bishop Joseph Lörks of the Society of the Divine Word Missionaries, the church had been proselytizing tribal locals since first arriving in German New Guinea—the kaiser’s protectorate in the northeastern part of the island—in 1896. The Catholic and Protestant missionaries had also worked in tandem to improve health care facilities on the island, the Catholic Holy Spirit Sisters starting small cottage hospitals and educating locals on childbirth and other health-related issues.

With the signing of the Versailles Treaty at the close of World War I, Germany was forced to hand over its protectorate to Australia. During the interwar period the missionaries nevertheless maintained good relations with indigenous New Guineans. But with the arrival of the Japanese in mid-1943, all that changed.

Soon after occupying New Guinea, the Japanese appeared unwilling or uninterested in differentiating between civilians from Allied- or Axis-aligned nations. The regional imperial naval command, headquartered in the Dutch East Indies, soon had Bishop Lörks and his missionaries exiled to Kairiru, off the coast of the provincial capital of Wewak. At first the military administrators permitted the displaced missionaries to move freely about the small island. Over time, however, Japanese officers began to regard the clergy as a possible threat.

After an uptick in enemy air raids, the Japanese suspected the ostensibly neutral missionaries of communicating imperial ship movements to the Allies. Unknown to the Japanese at the time, it was actually Allied coastwatchers—military intelligence operatives inserted behind enemy lines—who were monitoring Japanese shipping and reporting their movements to Port Moresby for action. The Japanese also suspected the missionaries of supportive contact with downed Allied aviators, an accusation with some merit. On being shot down over New Guinea, some U.S. and British airmen took to the jungle and likely sought to obtain food and medicine from the neutral clergy. Presumably, the aviators would have made contact through the indigenous people, most of whom harbored anti-Japanese sentiment. Finally, to the Japanese the German clergy’s good works represented an unacceptable taint of white colonialism in their Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

With all that in mind, in early March 1943 the chief of staff of the Japanese Eighth Fleet and the headquarters of the 81st Naval Garrison Unit, under the operational authority of the Southeast Area Fleet, issued orders to the commanding officers of the Japanese garrisons on New Guinea and surrounding islands: They were to gather all neutral civilians and put them aboard naval ships for transportation to Rabaul.

At the time of the order Akikaze’s captain, Lt. Cmdr. Sabe Tsurukichi, had berthed at Wewak to off-load food and medical supplies before sailing for Kairiru. On the afternoon of March 15 an officer and five crewmen went ashore in a landing craft and returned to the destroyer with Bishop Lörks, 38 German priests and nuns, a female New Guinean servant and two orphaned Chinese children. Akikaze then traveled northeast to Manus, where on the evening of the 17th it picked up 20 more civilians, including a half-dozen German Protestant missionaries, a Hungarian missionary, two plantation overseers and a handful of Chinese laborers. Once they were settled aboard, Akikaze set out east for Rabaul.

Around noon the next day, March 18, the destroyer made a scheduled stop at Kavieng on the island of New Ireland. The ship didn’t dock, and no one went ashore. But a military launch did motor out to the anchored vessel with a sealed envelope for Tsurukichi. As instructed, the captain waited until Akikaze was again at sea before opening the envelope. It contained orders to execute all civilians aboard. No reason was given.

Tsurukichi had thus far been benignly disposed to his wards and ensured they were well treated. However, an order from a superior was tantamount to an order from the emperor himself; to disobey was unthinkable, personal feelings aside. Assembling his officers, he read the order and immediately began preparations.

After wrapping boards in thick straw matting and placing them atop the stern deck, sailors assembled a crude wooden hoist over the platform, then suspended large sheets on either side of the structure to mask it from view. Meanwhile, the passengers were herded into a forward cabin. The captain then ordered the ship’s engines run at full speed to mask the noise of what was to transpire.

Tsurukichi’s men first came for the male captives. Taken to the bridge, they were asked, through an interpreter, their names, ages, nationalities and other details. Sailors then led them to the stern, one by one, where they were blindfolded. The Japanese led each man to the platform, tied ropes around his wrists and hoisted him upright. A firing squad of four riflemen and a machine gunner then shot him dead, and his body was unceremoniously pitched overboard into the destroyer’s wake. After disposing of the men, the Japanese repeated the entire process with the women. Finally, sailors grabbed the two orphans and tossed them alive into the ocean.

Over the course of three hours Akikaze’s crew had murdered nearly five-dozen civilians.

Having completed their gruesome task, the crew disposed of the passengers’ personal effects, dismantled the execution platform—its matting soaked with blood—and scrubbed the deck. Tsurukichi then presided over a brief ceremony to honor the spirits of the deceased, during which he ordered the men to never again discuss the “unfortunate case.” Akikaze reached Rabaul that night, where, according to one report, a Buddhist or Shinto priest was brought aboard to conduct a prayer service for the dead.

On Nov. 3, 1944, off the Philippines the submarine USS Pintado torpedoed Akikaze, which sank with all hands about 160 miles west of Cape Bolinao, Luzon. Thus the summary executions of Bishop Lörks and fellow missionaries aboard the destroyer went unknown until late 1947, when witnesses from Kairiru and Manus islands and two former Akikaze crewmen testified before the Australian War Crimes Tribunal in Hong Kong. By then, however, given the scale and prevalence of Japanese atrocities across the Pacific theater, Allied authorities had little motivation for prosecuting the surviving crewmen of a lost Japanese ship for a massacre committed more than a dozen years earlier.

Scores of official documents and histories of the war recount such horrific events, yet in Japan there persists a culture of denial regarding atrocities committed by imperial forces. Even one of the most brutal episodes, the 1937 Japanese occupation of Nanking—during which soldiers brutally murdered upward of 80,000 Chinese civilians and raped untold thousands of women—is referred to in present-day Japan as merely an “incident.”

Atrocities are all too commonplace in war, particularly amid such immense conflicts as World War II. Certainly, Allied forces had committed their share of war crimes, albeit on a far lesser scale. But why had the Japanese so hastily executed unarmed civilian missionaries? By 1943 the Allies had gained the upper hand in the Pacific War, thus it is possible the Tokubetsu Keisatsutai—the Imperial Japanese Navy’s secret military police—had deemed the missionaries’ presence on New Guinea an unacceptable threat to occupation forces. (Though smaller than its imperial army counterpart, the organization was no less murderous.) Or perhaps, given the imperial military’s strict bushido code and the setbacks Japan was suffering, it was inevitable commanders would seek out scapegoats for their military failures.

Of course, it is possible Bishop Lörks and his flock, despite their German nationality and supposed neutrality, were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Their fate was indeed tragic, and sadly, in the midst of a global conflagration, they went missing and largely unremembered in a veritable sea of lost souls.

Ken Wright, an Australia-based writer on military history and defense affairs, is the author of three books and numerous magazine articles. For further reading he recommends Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II, by Yuki Tanaka, and Ships From Hell: Japanese War Crimes on the High Seas in World War II, by Raymond Lamont-Brown.