One well-placed cruise missile or even a World War II torpedo could take out a modern aircraft carrier, but 90 years of success suggest these uniquely American weapons are here to stay.

The sight of an aircraft carrier up close, even at dockside, linked to land by umbilicals, is overwhelming—more than 1,000 feet long, displacing 100,000 tons, 30 stories tall from waterline to the ship’s island. The sense of power is undeniable. Each of the 90 planes operating from its deck carries a heavier bomb load than the largest bomber of World War II (not counting nuclear bombs). It takes no imagination to appreciate the sense of impotence a carrier can instill in a hostile power. Nobody wants a piece of this monster.

The carrier is the ultimate refinement of a weapon evolving from oar-powered galleys to wooden vessels that carried acres of sail and three decks of iron cannons to steel-hulled dreadnoughts that fired guns at ranges requiring corrections for the curvature of the earth. No other warship can launch supersonic aircraft against targets hundreds of miles away, recover them and launch them again, over and over. Capable of making 800 miles a day, it can quickly project power across the globe.

And the carrier is a particularly American man-of-war. Say “battleship” and you immediately think of the Royal Navy, Nelson, Trafalgar, Dreadnought and Jutland. Likewise, the submarine is the German man-of-war, the weapon that gave that nation the hope of winning two world wars. But the aircraft carrier is the vessel around which the United States built the greatest fleets in history. Ships like Enterprise under the direction of Admirals Raymond Spruance and William Halsey annihilated America’s only rival in carrier aviation—the Japanese. And since then, U.S. carriers have ruled the seas. No other nation has built so many. Today, of the 1,250 aircraft worldwide based aboard carriers, more than 1,000 are American. Carriers are part of the U.S. military’s DNA, deployed in some fashion by 12 presidents in more than 200 different foreign crises.

Despite their obvious success, the history of the carrier is anything but a smooth continuum. The very concept of the aircraft carrier has had to sail some rough seas. Initially, the military usefulness of the airplane itself was questioned, much less those that would operate from ships. In the view of generals who believed in horses and admirals who were devoted to battleships, the airplane was at best a useful tool for scouting and at worst a gimmick that distracted armies and navies. France’s General Ferdinand Foch articulated this view succinctly in 1911: “Aviation is fine as a sport. But as an instrument of war, it is worthless.”

Foch, like many other military leaders, eventually came around after World War I, saying: “The military mind always imagines that the next war will be on the same lines as the last. That has never been the case and never will be. One of the great factors on the next war will be aircraft.”

But even as the airplane gained respect during post–World War I debates over military doctrine, some of its staunchest backers wrote off the idea of flying from ships. Land-based planes and a strategy of massive bombing, they argued, would render carriers useless, defenseless and irrelevant. Even Brig. Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell, the insistent advocate of air power who was famously court-martialed for his trouble, saw the carrier as a “snare and a delusion.” It would be too vulnerable to land-based air power, he argued.

Perhaps the most assertive and influential theorist of air power and its role in future wars was Giulio Douhet, an Italian officer whose insubordinate advocacy of air power during World War I got him court-martialed, just as Mitchell later was. Douhet, though, actually did time. After serving a one-year sentence, he wrote The Command of the Air, which became both influential and controversial for its central thesis— that the next war would be won by fleets of heavy bombers that attacked cities, a vision of total war conducted by strategic bombing. Air forces and bombers would reign supreme, he argued. All other weapons and formations—armies, navies, fighter planes and warships—would be marginalized.

The climate was hardly friendly for the development of carriers. The United States’ mood had turned isolationist, and the economy had been hobbled by the Great Depression. There was no rush to spend money on defense. The Navy scrapped more ships, under terms of international treaties, than it built. Yet it did build carriers.

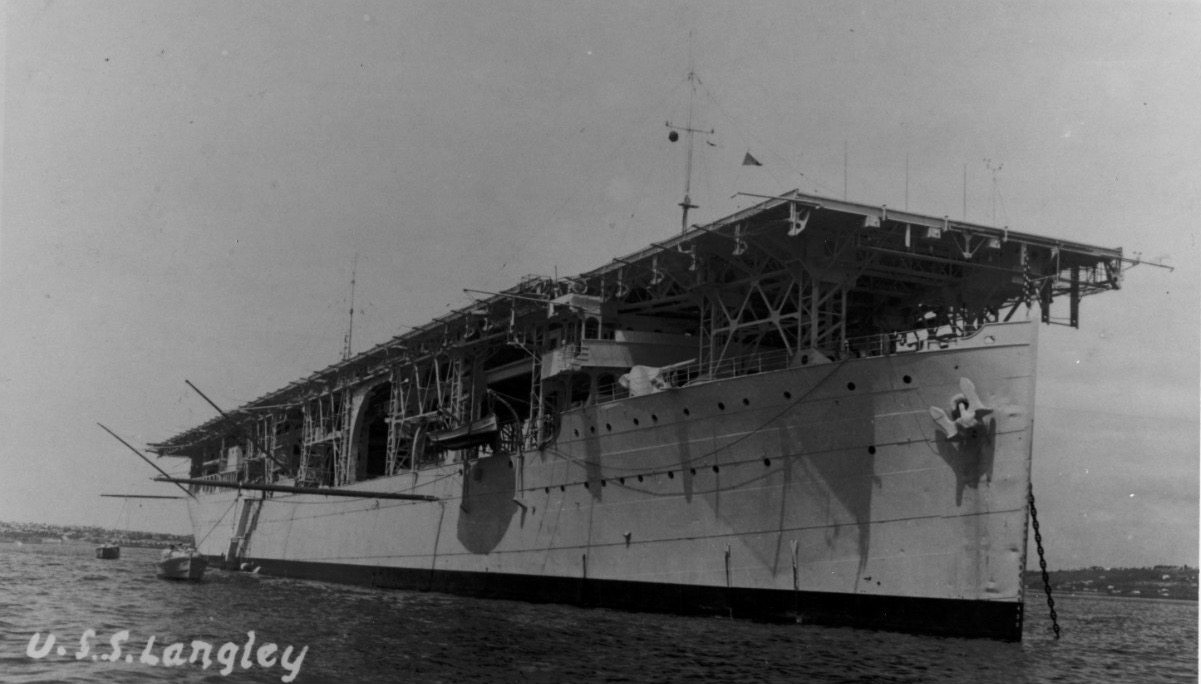

The first carrier had not been designed to launch and recover airplanes but to carry coal. USS Jupiter’s conversion to USS Langley was completed in 1922. It became the laboratory for the Navy’s first experiments with carrier-based aviation. Its planes were slow and flimsy—arrested on landing by cables attached to sandbags—but the tactical doctrines were sound and reached perfection when more substantial ships like Saratoga and Enterprise joined the carrier fleet. In 1937 Langley was converted again, to a seaplane tender assigned to the Pacific. While ferrying planes to the Dutch East Indies in the doleful weeks after Pearl Harbor, Langley was attacked by Japanese aircraft and so badly damaged that U.S. destroyers scuttled it.

At the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, the U.S. Navy had three carriers in the Pacific, all of which happened to be at sea. They survived while the battleships at Pearl were either destroyed or so badly damaged they were out of action for months. Most admirals at the time would have preferred it the other way around. The Navy put its faith in the big guns, and the plan, when war came, was to take on Japan’s battleships somewhere between Hawaii and Manila.

Instead, the decisive Pacific battle that gave the initiative to the United States became Midway. There, three American aircraft carriers ambushed four from Japan. Before dive bombers from Enterprise and Hornet began their attack on the morning of June 4, 1942, the Japanese were poised to win that battle. In five minutes, everything changed. There has never been such a sudden, dramatic and total reversal of fortune. At the end of Midway, all four Japanese carriers had been sunk. The United States lost one, Yorktown.

Midway made the aircraft carrier the supreme ship in naval warfare. (Army Air Forces Boeing B-17 pilots initially claimed they had sunk Japan’s carriers, but it turned out they had scored no hits at all.) Less obvious was the way in which the carrier—and the battle— seemed to play to U.S. strengths. Carrier operations were more fluid and improvisational than traditional Navy methods. And they were more democratic.

The flight deck of a carrier seemed like chaos but was in fact a smooth-running operation that depended on the skills and initiative of very young men. During battle, the most important decisions were not made by flag officers but by junior officers flying planes and depending on their own judgment and instincts. At Midway Wade McClusky, a mere lieutenant commander, could not find the Japanese fleet when the two squadrons of dive bombers he was leading arrived where that fleet was supposed to be. He had little time and less fuel. He decided to change course. A few minutes later he found the Japanese carriers preparing to launch against the American fleet, and he attacked.

Midway established the carrier, but its supremacy lasted until only three years later, when the atomic bomb was delivered by a Boeing B-29 bomber. The United States rushed to put all its eggs into one basket—the strategic bomber. Carriers were decommissioned. In 1949 construction on a new supercarrier, United States, was halted five days after the ship’s keel had been laid.

The years after World War II were filled with bitter bureaucratic fighting among the branches of the armed services for appropriations and the dominant role in the nation’s defense. The Douhet doctrines came back into vogue. The nation’s newest service, the Air Force, prevailed, and America put its trust in land-based aircraft, strategic bombing and the atomic bomb. Budget projections for 1949 called for the Navy to reduce the number of its heavy carriers from eight to four, and no one expected that would be the last cut.

Then in 1950 the North Koreans crossed the 38th parallel. Their forces moved so rapidly that it was thought imprudent to base planes on the ground in the South. Japan was too far away for the Air Force to be of much help. So naval aviation—in the form of the carrier Valley Forge—took up the initial slack. Carriers operated off the Korean Peninsula for the duration of the war.

Korea established the utility of carriers in conventional warfare. Their flight decks did not have to be defended against ground attack. They could move up and down the Korean coast at will, deploying where they could do the most good. They could refuel and rearm at sea and remain on station for weeks before returning to port.

So the U.S. Navy began building modern carriers—larger ships with steam catapults instead of hydraulic rams that sometimes exploded. One hydraulic explosion, on Bennington, killed more than 100 men in 1954.

The new ships were designed with angled decks so that planes that missed the arresting gear when landing could simply power up and go around for another pass instead of crashing into a steel barricade, the only option on older straight-deck ships.

Refinements allowed the Navy to operate faster, heavier aircraft like the McDonnell F-4 Phantom, which was state of the art during Vietnam. Carriers served in Vietnam from the first airstrikes over the North after the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident until the very end. Vietnam demonstrated the carrier’s value in limited wars but exposed its vulnerabilities on long deployments. Round-the-clock bombing made it necessary to store ordnance on deck, and inevitably there were accidents that would have been minor if the bombs and flares had been stored below, in magazines. Three fires did extensive damage and resulted in heavy casualties aboard Oriskany, Forrestal and Enterprise.

Carriers seem to be most effective when used in short, fast actions, raids and intense battles, after which they disengage and resupply. (Refueling is no longer an issue because of nuclear power.) But war seldom follows theory. And the carrier is nothing if not versatile, another way in which its character is vividly American. No nation’s military is less doctrinaire and more improvisational. During the early days of World War II, for example, when the United States desperately needed a morale-building event, a carrier provided the answer. A handful of Army Air Forces pilots learned how to get a North American B-25 bomber into the air off a very short runway. Under the command of Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle, they took off from the deck of Hornet and attacked the Japanese mainland only four months after Pearl Harbor.

The Doolittle Raid did not accomplish much militarily, but it did worry the Japanese into an action that resulted in the Battle of Midway, and it gave American citizens an emotional lift. When he described the raid, President Franklin D. Roosevelt said the planes had taken off from a secret base, which he called Shangri-La, a name he lifted from the novel Lost Horizon. Later the Navy commissioned an attack carrier named Shangri-La.

American carriers have fought in major battles like Midway, con- ducted sustained operations during Korea and Vietnam, and recovered astronauts returning from space. The helicopters used in the ill-fated 1980 operation intended to rescue American hostages in Iran were launched from a carrier. After the recent tsunami that struck Indonesia, a carrier was deployed to provide disaster relief.

When Eisenhower sailed to the Persian Gulf last fall, followed by Stennis in February, Washington was sending strong diplomatic signals of its disapproval over Iran’s effort to build a nuclear bomb and its meddling in Iraq. Speeches in the United Nations, backchannel diplomatic meetings and strong language in press conferences do not concentrate the mind the way aircraft carriers just over the horizon can.

Given the uneasy and tense world we live in, it seems likely that aircraft carriers will be kept busy for years to come.

Originally published in the April 2007 issue of Military History. To subscribe, click here.