Mississippi suffered greatly throughout the Civil War, but it was at Corinth where citizens and volunteers first endured the carnage of war amplified by a bloody clash deep in the Tennessee wilderness. Early on, gaining possession of Corinth—an important railroad junction in northeastern Mississippi—garnered immediate attention from both Union and Confederate commands. Tucked away in a swampy lowland and divided by jagged ravines and dried-up creek beds, Corinth presented an arduous physical challenge for the massive armies that converged on the town. So it was in the spring of 1862 that the Civil War found Corinth and brought along the reality of a long and bloody struggle.

Shiloh was Corinth’s prelude to war. As for the inexperienced civilian-soldiers, the reality of the combat experienced there was a shock. Most combatants who survived the fight left the battlefield wholly bewildered, unable to process what seemed like an entirely new way of war. Veteran’s recollections of Shiloh and Corinth—some of them written decades later—give us insight into the brutality of this devastating war.

Confederate Captain Francis A. Shoup, Mississippi Private Augustus Mecklin, Ohio Captain George Rogers, and Confederate nurse Kate Cumming experienced Shiloh and the action around Corinth through different lenses. Shiloh was Shoup’s first brush with intense combat. So traumatic was the fight that following the war the sight of budding trees immediately transported him back to the spring of 1862. The fight also scarred the young Mecklin. So much so that he did not and would not see the war through. Others like the ardent abolitionist Rogers and the passionate Cumming were inspired by their experiences and were determined to see the end—no matter the cost.

Before war touched those combatants, however, their fates were dictated by decisions of untried commanders unprepared to direct war on such a large scale. In February 1862, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston waffled under such pressures. Johnston had to stop his retreating armies and devise a plan to counter the Union offensives from western and eastern Kentucky. On February 5, 1862, General P.G.T. Beauregard arrived in Bowling Green, Ky., to assist Johnston with conjuring a stopgap for the crumbling Confederate defensive line. But Johnston offered no practical solution for halting the Union thrust toward Tennessee. Beauregard quickly suggested a concentration of Confederate forces at Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Johnston agreed—somewhat—and sent 15,000 troops to defend the route to Nashville. Nevertheless, the force was insufficient, and Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River fell after a few weeks. For the “victor of Donelson,” Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, an unchecked advance down the Tennessee River into Alabama and Mississippi became a reality.

In a rush to establish a rallying point for his receding commands, Johnston suggested to Beauregard the northeastern Alabama town of Stevenson. Yet again, Johnston’s suggestion puzzled the Creole who countered by hinting at converging the forces at Corinth. Johnston concurred and in early March 1862, approximately 40,000 Confederate troops from all over the south assembled at Corinth for a counteroffensive against the Union advance down the Tennessee River.

Thus, Corinth became the staging point for a showdown between Grant and Johnston. The sleepy town transformed into a dusty military hub and quickly filled up with excited Confederates enthralled at the idea of striking back at the captors of Fort Donelson. The enemy that many Confederate soldiers imagined as inferior fighters were much like themselves, however. Grant’s Army of the Tennessee and Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio were “Westerners”—men from Iowa, Missouri, Minnesota, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and Wisconsin. Farmers, tradespeople, rural schoolmasters, and pious preachers made up the majority of both contending armies at Shiloh. Confederates from Alabama, Arkansas, Tennessee, Mississippi, Louisiana, and Texas ran into a familiar foe at Shiloh, and though green, they too were determined to conquer.

‘The first leaf of spring’

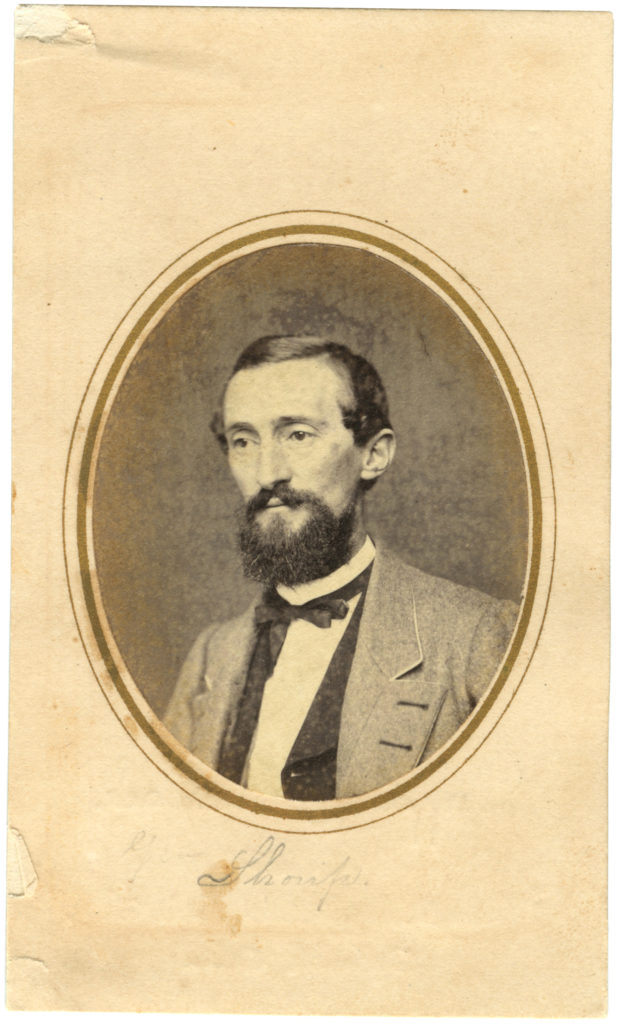

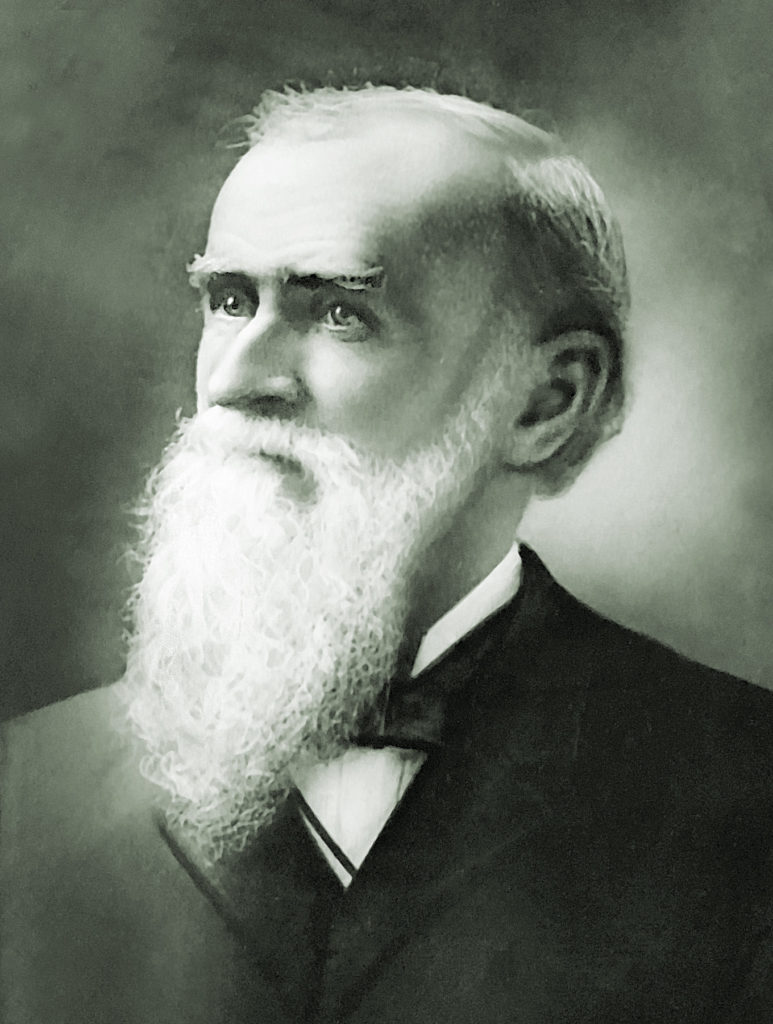

Three years before his death in 1896, ex-Confederate Francis Asbury Shoup sat down for an interview with the Confederate Veteran. In the twilight of his life, Shoup reminisced over the Vicksburg and Atlanta campaigns with remarkable detail and, like many ex-Confederates, cast blame of shortcomings upon his superiors. But for Shoup, a former captain and chief of artillery for William Hardee’s Corps, he began his story on April 5, 1862. He recalled the 23-mile slog from Corinth, and riding about the battle lines of Hardee’s Corps in deep reflection.

The Confederates were only a few miles from the Union encampment at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn. Shoup and his men bided their time listening to merry Federal camp tunes and taking in the tranquil scenery in a rare reprise from the rain. “[We] had plenty of time to look at the dogwood blooms, of which the woods were full.” The old soldier recalled: “I never see them now that I do not think of Shiloh.” Further to the rear, Private Augustus Hervey Mecklin, Co. I, 15th Mississippi Infantry, did not have the ear of a general or of any officer for that matter. A few days after the Battle of Shiloh, Mecklin wrote an intense letter to sort out what he saw. But on April 5, he lay only a couple thousand yards behind Hardee’s lines. Prophetically, he thought of his comrades’ impending demise and the scores of grieving mothers back home. Perhaps Mecklin looked to the sky for guidance. He noted: “The trees were budding into the first leaf of spring.”

As dusk set in on April 5, Captain Shoup trailed Hardee to a council of war called by Johnston. Shoup was not present at the conference with Johnston’s corps commanders but waited on the outskirts of the meeting. Afterward, Hardee informed Shoup of the situation. According to Shoup, Hardee was discouraged about the assault the next day. In addition, most of Johnston’s corps commanders reciprocated the feeling. Shoup affirmed during his interview with Confederate Veteran that Hardee confided to him afterward: “After listening for sometime Gen. Johnston cut them short by saying, ‘Gentlemen, return to your commands; the attack will be made at dawn. If the men have no rations they must take them from the enemy.’ ”

Shoup believed until his dying day that “we [the Confederates] came that near turning tail, even at the last moment.” But unfortunately for Shoup, Mecklin, and tens of thousands of others, no retreat was sounded. As historian Timothy B. Smith puts it best: Johnston cast the “iron dice of battle.” There was no going back.

The morning of April 6 was “very warm,” Mecklin recalled. “The sky was clear and but for the horrible monster death who now pile high carnival, this might have been such a Sabboth [sic] morn as would have called pleasant recollections of Sabboth bells & religious enjoyment.” As he and the 15th Mississippi waited for their chance for a glimpse of ‘the elephant,’ Captain Shoup, attached to the first Confederate assaulting force, rode manically through rough underbrush and low-hanging branches in search of anyone to give him orders.

While dodging monstrous splinters, Shoup recollected catching sight of the foe: “It seems that the enemy was just sending out some scouts, at any rate our skirmishers were engaged very early.” Glancing about, Shoup quickly realized “it was all haphazard—line against line—patching up weak places with troops from anywhere they could be got.” He lamented “for several hours the [f]iring was constant.”

From about 7 a.m. to 11 a.m., the battle progressed methodically. At first contact just before 6 a.m., Johnston’s raw regiments had orchestrated a disorganized lunge at a momentarily startled Union force. But under the direction of Brig. Gens. William T. Sherman, Stephen Hurlbut, and W.H.L. Wallace, the Federals worked an effective delaying defense as Grant constructed a formidable defensive line near Pittsburg Landing. Meanwhile, inexperienced troops on both sides maneuvered awkwardly through dense foliage.

The carnage was severe. Artillery on both sides tore limbs from man and tree. At 9:30 a.m., the Union right began to crumble and fell back to the Tilghman Branch around Jones Field. There Sherman and McClernand scrambled to steady their raw troops in face of a rapidly regenerating Confederate advance. It was there where Augustus Mecklin and the 15th Mississippi deployed to one of the battle’s epicenters: Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss’ camp along the Hamburg-Purdy Road.

Mecklin recalled his callow unit’s advance: “Just at this juncture while making a rapid march at double quick one of our Liets [lieutenants] was shot through the hand accidentally by his own pistol & just at the same moment almost, our adjutant, the Lieut’s Bro., was stabbed accidentally in the thigh. With a bayonet.”

The 15th Mississippi continued forward, advancing uncertainly toward disorganized but stabilizing Federal lines. As the Mississippians bypassed booming batteries, Mecklin recorded their gruesome effect: “Here & there we saw the bodies of dead men—friends & foes lying together. Some torn to mince meat by cannon balls. Some still writhing in the agonies of death. We halted for a short time near where a poor fellow was lying leaning against a tree severely wounded.”

In awe of the terrific noise, he added, “The cannon appeared to be carrying on this contest wholly among themselves.” While taking shelter at a tree line, Mecklin longed to escape the exposed position: “Some of the balls reached us & while we were halted one struck a tree nearly a foot through & splitting it a sunder tore a poor fellow who was behind it into a thousand pieces.”

The Mississippians, however, pressed on. In the advance, Mecklin looked about and recalled the image of the idyllic atmosphere torn by hot iron and lead: “The trees were spotted with bullet holes. Many branches & tree tops not budding into the tender leaf of spring bowed their heads, torn partly from the forest stem by the balls of both sides.”

When the Mississippians reached volleying distance, Mecklin’s fears became reality: He caught a glimpse of the elephant. “For the first time in my life, I heard the whistle of bullets,” he recalled. “We took shelter behind the tents & some wagons & a pile of corn & returned the fire of the enemy with spirit.” With exasperated prose, Mecklin continued: “The bullets whistle around my ear. I was near the front & firing. lay down to load soon men were falling on all sides.” Around him, comrades fell: “Two in Co. E just in front of me fell dead shot through the brain. On my left in our own Co., W. Wilson, W. Thompson & Ben. Stewart. Bro. Geo. & James Boskins were wounded.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Mechanically, Mecklin went to work, doing his best to block out the destruction. He fired so rapidly, in fact, that his rifle gummed up: “…my gun got so foul that I could not get my ball down. Taking a short stick that lay near, I drove the ball down. Again the tube became filled up & not being able to get it off, I called to one of Co. E. to throw me the gun of a wounded man by him. I fired this until the tube became filled. Throwing it down I went to the rear & picking up my ho’ gun held on until the battle was over.”

At the epicenter of the fighting, Mecklin and Shoup were not aware the Confederate high command was in some disarray. Johnston had died from a mortal wound; his replacement, Beauregard was battling illness and spent, mistakenly confident the battle had already been decided—that the Federals were not in position for an effective response. The 15th Mississippi had been fighting for 12 straight hours, and as night fell, Mecklin expressed his relief: “Long had I looked for the kind hand of darkness to lay its peaceing hand upon this savage conflict.”

Mecklin would survive the next day’s fighting in what became a remarkable Federal victory. He also survived his army’s miserable retreat to Corinth and the subsequent 31-day siege of the city. But Shiloh tarnished his soul. He resigned from the Confederate Army later that year and returned to ministry, never fully coming to grips with the whirlwind he and his comrades had encountered in the Tennessee wilderness.

A clash in Jones Field

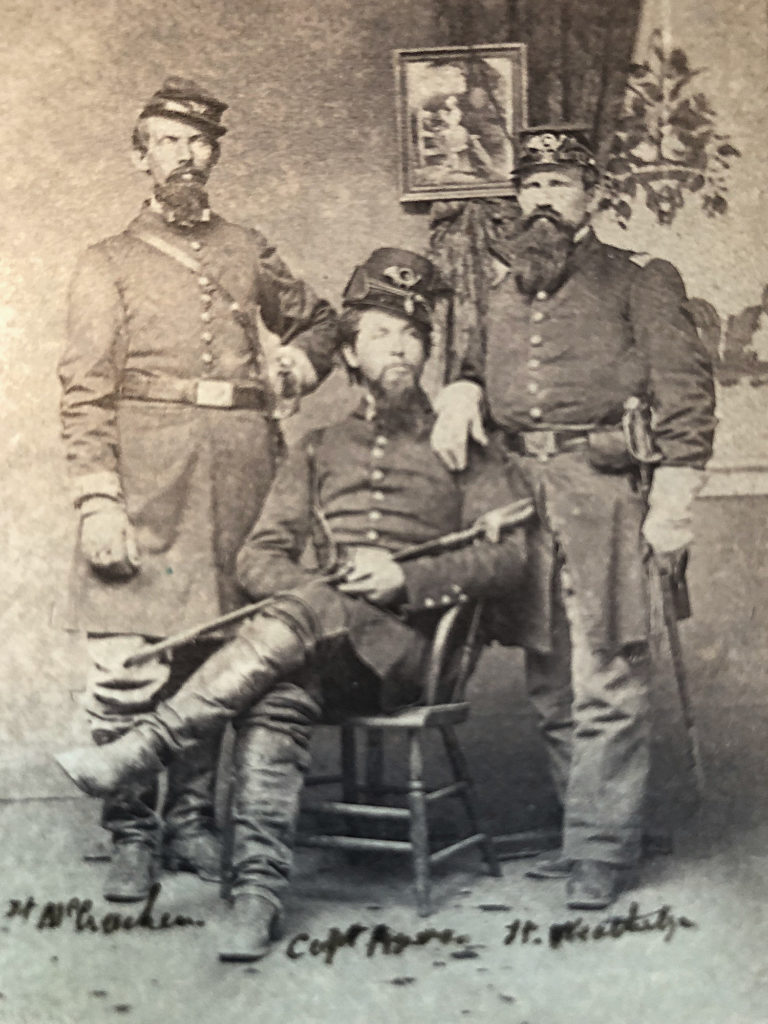

At 5 a.m. April 7th, 1862, Maj. Gen. Lew Wallace’s wayward 3rd Division lined up on the right as part of Grant’s planned counterattack. Wallace become lost trying to reach the battlefield the day before and arrived too late to figure in the fighting. George Rogers, the 25-year-old captain of the 20th Ohio’s Company A, rode ahead of his men as the attack lurched forward. A veteran of Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s 1861 campaigning in western Virginia he was not quite prepared for what lay ahead. Meandering to the left, the 20th came upon Colonel Preston Pond’s Louisianans in Braxton Bragg’s Second Corps secluded along with Captain William Ketchum’s Alabama Battery in Jones Field. Muskets began to rattle and, while urging his men on, Rogers glanced at the enemy lines. He saw an excited Confederate officer, flag in hand, desperately rallying his wavering lines. Rogers suspected it was Beauregard himself, but it was most likely Pond.

A few days later, Rodgers wrote of his contact with Pond’s “Creole” brigade: “Our brigade came by a beautiful and rapid movement upon a heavy battery of the enemy’s, supported by a brigade of Creoles commanded by Beauregard in person, who—with flag in hand at the head of the brigade—was endeavoring to rally his forces for a final effort to retrieve his lost fortunes.”

Rogers and the 20th Ohio moved cautiously into Jones Field. The enemy forces would exchange volleys for the next three hours. Eventually, Wallace’s division picked up speed mid-morning and rushed over Pond’s disheveled brigade. The Ohioans pitched into the fleeing Confederates. As Rogers guided his lines, he was distracted by the strange actions of one shaken officer, “weeping like a child” at the sight of his mutilated mount. Mercifully, the officer unloaded six shots into the dying animal. “That scene,” Rogers lamented, “…remains the most vividly painted in my memory of all those I saw on that memorable day.”

By 4 p.m., the exhausted and severely bloodied Confederate army began its staggered retreat to Mississippi. Making the situation more dire was an intense rainstorm that turned the roads into a nearly impassible quagmire. Fortunately for the severely wounded, volunteer nurses scrambled from surrounding Confederate states to assist in any possible way. As the fighting raged on April 7, Alabamian Kate Cumming heard of the massive fight and boarded a train from Mobile, Ala., to Okolona, Miss., and from there to Corinth. Cumming observed trains loaded with grievously sick and wounded heading into the opposite direction and recorded on April 8: “It is raining in torrents. Nature Seems to have donned her most somber garb, and to be weeping in anguish for the loss of so many of her nobelist [sic] sons.”

Nursing the Wounded

Shiloh’s aftershock quickly expanded to towns and settlements in Tennessee and Mississippi. Corinth instantaneously felt the blow. Fortunately, Kate Cumming and many civilian volunteers were there to help. She had arrived on April 11, towing a heavy heart because her two brothers—one in Ketchum’s Alabama Battery, the other in the 21st Alabama Infantry—had possibly been killed during the battle. While in transit from Okolona, Cumming wrote in her diary: “There is a report that Captain Ketchum is killed, and all of his men are either killed or captured; the Twenty-First Alabama Regiment has been cut to pieces. I was never more wretched in my life! I can see nothing before me but my slaughtered brother, and the bleeding and mangled forms of his dying comrades.”

With uncertainty on her mind, Cumming kept busy nursing the sick and wounded. On April 12, she “sat up all night, bathing the men’s wounds, and giving them water. Everyone attending to them seemed completely worn out.” The afflicted soldiers seemed crammed into every crevasse: “The men are lying all over the house, on their blankets, just as they were brought from the battle-field. They are in the hall, on the gallery, and crowded into very small rooms.”

It was the scent of war, however, that disturbed her most: “The foul air from this mass of human beings at first made me giddy and sick, but soon I got over it.” Yet she remained and Corinth’s atmosphere of suffering only intensified with time. A week later, desensitized somewhat, Cumming wrote about a soldier knowing “he will die.”’

“A young man whom I have been attending is going to have his arm cut off!” she recorded on April 23. “Poor fellow! I am doing all I can to cheer him. He says he knows he will die, as all who have limbs amputated in this hospital have died.”

Her senses dulled by stress and the sight of human suffering, Kate Cumming concurred with the doomed boy: “It is but too true; such is the case.”

For the thousands of victims of Shiloh who sought refuge behind the entrenchments of Corinth, a true challenge of survival approached in the form of climate. The month of May brought excessive heat and dryness, and severe illness incapacitated entire units. Potable water was almost nonexistent, and many soldiers lapped liquid out of stagnated puddles and swamps. The lumbering Union army finally reached the outskirts of Corinth during the last week of April, and Corinth’s desperate inhabitants again braced for the relentless horrors of war.

Shoup, Mecklin, Rogers, and Cumming all converged at Corinth, but the ghosts of Shiloh followed. Though they all survived the war, vivid memories of Shiloh haunted them the rest of their lives.

After working as a concrete mason for 15 years, Trace Brusco changed career paths and is currently a Ph.D. student at the University of Alabama, where he studies military history. His current project focuses on Corinth, Miss., and how the Civil War impacted northeastern Mississippi.