William Merrill elevated cartography to a science that helped Union commanders win the war

IN HIS MEMOIRS, William Tecumseh Sherman wrote that his saddlebags always contained four essential items: “a change of underclothing, a flask of whiskey, cigars, and my maps.” Sherman believed that accurate maps were invaluable to the success of any military campaign and came to value the skills of the topographical engineers of the Army of the Cumberland above all others. He knew they were men trained to exacting standards. While Jedediah Hotchkiss, Stonewall Jackson’s chief topographer, is probably the best known Civil War mapmaker, it was Lt. Col. William Emery Merrill, more than anyone else, who advanced the field. Merrill took a task that had been done by gifted amateurs or army engineers working part-time and elevated it to a science performed by professionals whose only job was to produce military maps and keep them up-to-date. While many of Merrill’s maps are preserved at the Library of Congress, the man himself has almost slipped off the pages of history. Almost, but not completely.

Merrill might never have drawn a single map had his father not died when the boy was nearly 10. Captain Moses Merrill was killed leading the 5th U.S. Infantry at the 1847 Battle of Molino del Rey during the Mexican War. Because Merrill was an 1826 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, his death allowed President Franklin Pierce to nominate the captain’s eldest son to West Point as a legacy candidate from Fort Howard, Wis., in 1854. Merrill didn’t disappoint. He graduated first in the Class of 1859 and, after several field assignments, was teaching engineering at West Point when the Civil War broke out.

The first wartime assignment for Merrill, a newly minted second lieutenant, was to the Department of the Ohio, where he performed work typically done by army engineers. He supervised the construction of fortifications at Red House, Md., and on Cheat Mountain in Virginia (now West Virginia). During the September 12-15, 1861, Battle of Cheat Summit Fort, Merrill and 64 other Union soldiers were captured during multiple—albeit unsuccessful—Confederate assaults. It was Merrill’s first time under fire and General Robert E. Lee’s inauspicious Civil War debut.

Merrill was sent to Richmond and remained there as a prisoner of war until February 1862. After a brief parole, Merrill was sent to Fort Monroe, then assigned to the Army of the Potomac. Major General George B. McClellan’s methodical march up the Virginia Peninsula toward Richmond needed engineers to prepare siege emplacements and encampments for more than 100,000 troops. While assigned to the staff of 4th Corps commander Maj. Gen. Erasmus Keyes, Merrill was almost killed on April 16, 1862, by a shell fragment while reconnoitering Confederate artillery positions with skirmishers of the 3rd Vermont Infantry near Lee’s Mill just outside Yorktown, Va.

The swampy ground of the Warwick River made sighting enemy positions difficult to do from a distance. In Brig. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s report of the engagement, he noted “the handsome manner in which Lt. Merrill and Lt. Bowen, the engineers, made their observations under the enemy’s fire and in short range of their guns.” Merrill was breveted captain for his gallant conduct.

After recuperating in Washington, D.C., Merrill took temporary charge of the army’s construction projects to strengthen the protective ring of forts around the federal capital. He then went west as superintending engineer to supervise the building of defenses around Newport and Covington, Ky., just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati, then being threatened by Maj. Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith’s Confederate raiders. From November 1862 to March 1863, Merrill served as chief engineer of the Army of Kentucky, assigned to construct defenses along the Kentucky Central Railroad. After that, Merrill helped fortify Franklin, Tenn., and improved the defenses at Fort Donelson and Clarksville, Tenn.

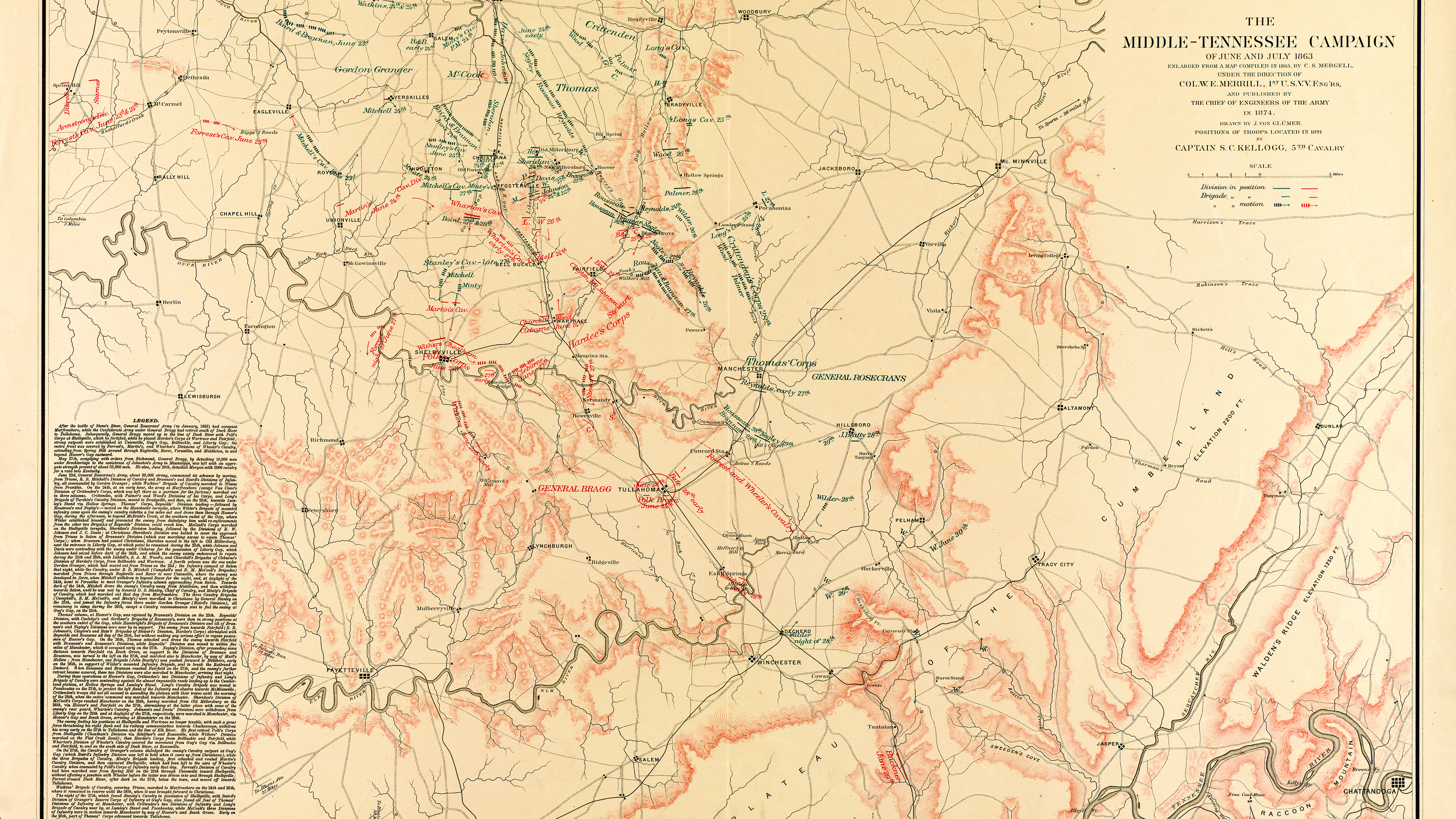

On May 29, 1863, Merrill’s life as an itinerant engineer ended and the era of professional mapmaking began. Before the war, Union Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans spent 10 years with the Engineer Corps and knew the value of accurate maps. He used them in Western Virginia early in the war; many of McClellan’s triumphs there in 1861 were due to Rosecrans’ considerable geographic knowledge and the study of available area maps. After his victory at the Battle of Stones River in January 1863, Rosecrans knew his next objective would be to drive Confederate forces out of Middle Tennessee and capture Chattanooga. His newly formed Army of the Cumberland would need accurate maps to comprehend the region’s diverse geography.

With General Orders No. 124, Rosecrans announced that Merrill would be “engineer officer in charge of the topographical department….All corps, division, and brigade topographers will be under the professional direction of Capt. Merrill.” That order changed how military maps would be made and helped the Army of the Cumberland create and sustain the Union’s best corps of topographers.

Merrill left no detail to chance. He required an up-to-date list of all brigade and division topographical engineers along with a list of the instruments and drawing materials they had on hand. He asked for estimates of the type and amount of supplies each engineer would need to do his job. He even issued a pocket-sized field sketchbook containing standardized symbols for good wagon roads and bad, footpaths, rivers, creeks, marshes, towns, buildings, and other items that should appear on a good military map. This allowed mapmakers and officers to read any map and come away with the same kinds of information.

Maps had to be drawn on paper ruled with one-inch squares. Transferring information from existing maps would be done only in lead pencil and new information or corrections entered using colored pencils. Each brigade and division topographer reported his activities to Merrill every week, providing “copies of all special maps and reconnaissance (complete or not) made by him or under his direction, including all verbal or written topographical information.” This enabled Merrill to produce and distribute to all commanders maps containing the latest information available to the army. Department headquarters would produce the finished product known as an information map.

All officers were required to assist the topographical engineers and not to assign them other duties as they conducted their mapmaking assignments. Overall, Merrill urged his topographers to “find out all you can which can affect military movements in the country investigated, particularly the character of road and the supplies of grass and water.”

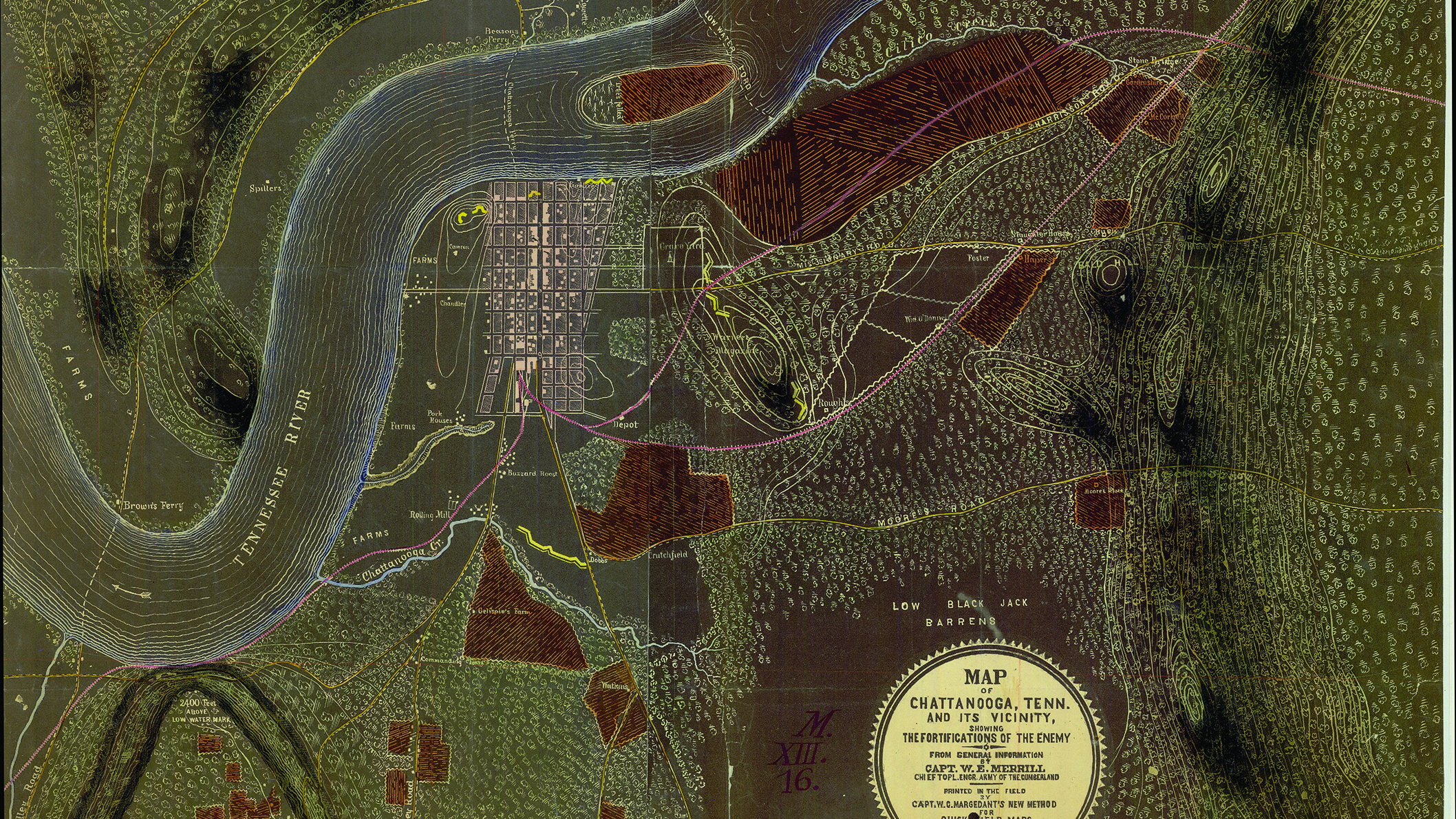

After six months of inactivity around Murfreesboro, Tenn., Rosecrans finally put his army into motion on June 24, 1863. By then, his commanders had studied maps showing the roads leading east to the Tennessee River, calculated their capacities and limitations, and pinpointed locations where they could find water and forage. Rosecrans incorporated new information supplied by his mapmakers into his detailed daily marching orders. By the time his campaign ended on July 3, 1863, Rosecrans had deftly maneuvered Confederate General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee completely out of Middle Tennessee. At the price of only 560 casualties, Rosecrans had swept forward 80 miles to the banks of the Tennessee River. Known as the Tullahoma Campaign, it is considered one of the war’s most tactically brilliant operations. By the time Union forces reached the outskirts of Chattanooga, mapmaking had become an integral part of the Army of the Cumberland’s war-making capability. In his report of the campaign, Rosecrans paid tribute to the “ability of Capt. W.E. Merrill, engineer, whose successful collection and embodiment of topographical information, rapidly printed by Capt. William C. Margedant’s quick process, and distributed to corps and division commanders, has already contributed very greatly to the ease and success of our movements over a country of difficult and hitherto unknown topography.”

But Old Rosy’s days with the Army of the Cumberland were numbered. After the humiliating defeat at Chickamauga on September 20, 1863, Rosecrans retreated into the defenses of Chattanooga. He allowed the Confederates to occupy all the high ground around the city, trapping his tired, hungry army. When Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant arrived on October 23, sent by Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to assess the situation, he relieved Rosecrans of his command and gave the Army of the Cumberland and its mapmakers to Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas.

Thomas was a skillful mapmaker himself. From his earliest campaigns, he kept his own pocket map journal in which he recorded the topography of the countryside where he was fighting. Thomas drew a map on one page and on the opposite page kept notes on terrain, road conditions, depth of fords, the height of hills and mountains, the availability of drinking water, and forage. This narrative “map memoir” contained information that could not be translated graphically but might be useful for successful military campaigning. Thomas knew that the next theater of operations would be North Georgia and he set his mapmakers to work.

In March 1864, Grant went east to take command of all the Union armies. He assigned his old friend, Sherman, to overall command of all Union forces west of the Alle-

gheny Mountains. Sherman knew that the topographical engineers of the Army of the Cumberland, men trained to Merrill’s exacting standards, were better than those in any other army and he retained them as the chief topographers for the new army he was assembling for his thrust into Georgia. Sherman intended to open the ball against Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston and his Army of Tennessee, waiting behind strong defensive fortifications at Dalton, Ga., about 30 miles to the southeast, on May 5, 1864, to coincide with the beginning of Grant’s Overland Campaign in Virginia.

The terrain between Chattanooga and Atlanta is a tangle of winding ridges, narrow passes, swift running rivers, rocky stream fords, and red clay farm roads—hardly ideal topography for an invading army of 100,000 men and 35,000 animals to traverse. A “plat map” of the land known as the Cherokee Purchase had been drawn in the 1840s to show townships and sections. Union mapmakers wanted to use copies of that map to pinpoint specific landmarks.

Merrill and his staff worked on a map of northern Georgia throughout the winter of 1863-64, using James R. Butt’s Map of the State of Georgia as a guide. But just days before Sherman intended to begin his offensive, the U.S. Coast Survey in Washington, D.C., forwarded smaller-scale maps of the area to his headquarters in Chattanooga. Merrill had not yet distributed copies of the huge original, waiting to incorporate the latest information brought in by Sergeant Nathan Finnegan of the 4th Ohio Cavalry. Finnegan had painted signs, frescoes, and portraits before the war. Now he excelled in gathering information from an array of spies, scouts, refugees, travelers, prisoners, peddlers, and itinerant preachers—the local flotsam who could supply the critical tidbits of information that meant the difference between a poor military map and a good one.

Like Rosecrans and Thomas before him, Sherman emphasized the importance of maps to all his unit commanders. On May 31, 1864, Special Field Orders No. 15 listed guidelines “to secure the rapid and efficient co-working of the topographical engineer departments of the army in the field.” According to Sherman’s order, the duty of topographical engineers was “making purely military surveys.” When on the move, they would survey the route of their commands. When the army halted, these surveys would be consolidated and new maps issued. Finally, Sherman ordered all commanders to assist their topographical engineers in order to “secure the data from which to compile, at the earliest moment, maps which are indispensably necessary in military movements…”

Sherman insisted all his officers be able to work from the same map, but he gave Merrill little advance notice of his marching plans. “Two days before the army started from Chattanooga on the Atlanta Campaign I received notice of the intended march,” Merrill would write. “Up to this moment there was but one copy of the large map of Northern Georgia, and this was in the hands of the draughtsmen.”

After the war, Merrill described his frantic efforts to get 200 copies of the map printed and distributed to Sherman’s commanders: “The map was immediately cut up into sixteen sections and divided among the draughtsmen, who were ordered to work night and day until all the sections had been traced on thin paper in autographic ink. As soon as four adjacent sections were finished they were transferred to one large stone and two hundred copies were printed. When all the map had thus been lithographed, the map mounters commenced their work….The copies for the cavalry were printed directly on muslin, as such maps could be washed clean whenever soiled and could not be injured by hard service.” Never given to self-promotion, Merrill nevertheless proudly concluded that “before the commanding generals left Chattanooga, each had received a bound copy of the map, and before we struck the enemy, every brigade, division, and corps commander in the three armies had a copy.”

As the Union juggernaut rolled on, Merrill had troops seize maps in county clerk’s offices and made sure cavalry patrols rounded up local surveyors and engineers for their maps. Troopers would stop at local residences as they advanced to ask for township and section numbers, allowing new area maps to be drawn on a grid pattern. For the first time, commanders could use coordinates and refer to positions using a system of numbers. Merrill knew that “in this manner we can obtain fixed points and thus obviate one of the greatest difficulties in mapping a new country.”

Though Merrill conceded his maps would be less accurate the deeper the army penetrated into enemy territory, he contended, “It was still valuable even where its information was defective, because every subordinate…had the same map as the commanding general, and…knew at once from the nature of his orders what he was expected to do.” The army Sherman led to Atlanta, Merrill boasted, was “the best supplied with maps of any that fought in the [war].”

Despite Merrill’s indispensable help, Sherman chose his own chief engineer, Orlando Metcalfe Poe—an expert in bridge, road, and pontoon building—to chart the progress of the army as it swept across Georgia and through the Carolinas. Merrill returned briefly to Chattanooga to form a congressionally approved regiment of Veteran Reserve Engineers, tasked with constructing defenses for 850 critical miles of single-track railroad in the Western Theater. Merrill designed more than 160 blockhouses, most at critical points such as bridges, that were resistant to small-caliber field artillery carried by cavalry and could be manned by as few as 30 men.

Merrill stayed with the Army Corps of Engineers postwar, becoming a lieutenant colonel in February 1883. From 1867 to 1870, he served as chief engineer on the staff of Sherman, then commanding the Military Division of the Missouri. Thereafter, until his death, he was engaged on governmental engineering work. He was chief engineer on one of the largest projects undertaken by the Corps: construction of locks and canals on the Ohio River below Pittsburgh.

In 1889, Merrill represented the Engineering Corps at the International Congress of Engineers in Paris, but two years later died of heart failure while traveling by train near En-

field, Ill. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Gordon Berg is a freelance writer from Gaithersburg, Md.

_____

Southern Exposures

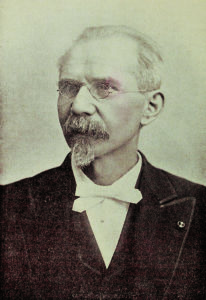

Captain William C. Margedant (right) had been Rosecrans’ chief topographical engineer prior to Merrill’s appointment, and his “quick process” of duplicating maps was critical to Rosecrans’ Tullahoma Campaign success in June-July 1863. A native of Prussia, Margedant worked as an architect and engineer in Cincinnati before serving as captain in the 10th Ohio Infantry. While on Rosecrans’ staff in Western Virginia early in the war, he invented a method for quickly duplicating maps in the field. His “photo-printing devise” [sic] consisted of a light box containing chemically treated India rubber baths fitting inside one another. Printing was done by tracing a map on thin tissue paper, placing itover photographic paper treated with nitrate of silver, and exposing it to the sun. This produced a negative copy of the map with roads, rivers, and other landmarks appearing white on a dark background. Sections of the map could be stitched together on canvas or cloth, varnished, and

then distributed each night to all corps, divisions, and brigades, as well as individual regiments operating alone. Margedant’s staff consolidated notes received daily from the topographical engineers, revised the master tissue, and, with little delay, maps and charts containing everything ascertained the day before were in the hands of all commanding officers.–G.B.

This story appeared in the November 2019 issue of America’s Civil War.