In 1887, an adventure novel written by a 27-year-old for a little extra cash was published in the Christmas edition of a British paperback magazine. It would forever change the face of popular culture and usher in a whole new genre of story.

The story, called “A Study in Scarlet,” was the first appearance of the immortal Sherlock Holmes and his colleague Dr. Watson, a pair now so colossally influential that subsequent detectives have yet to emerge from under their massive shadows.

The Inspirations for Sherlock Holmes

Holmes didn’t spring fully formed from the mind of Arthur Conan Doyle, of course. He was largely modeled on Dr. Joseph Bell, a Scottish medical professor whose ability to diagnose patient’s complaints through minute observations and brilliant deductions made a lasting impression on Conan Doyle when he was a young medical student.

When Doyle took up his pen to write, the detective genre as we now know it had few examples to draw from, but one notable pre-Holmes character that served as an inspiration was the 1841 Edgar Allan Poe detective C. Auguste Dupin, who was an early prototype of the model Doyle would now popularize: a brilliant amateur detective gifted with both a narrator sidekick and an ability to observe and infer. Dupin’s perceptive talents allowed him to solve mysteries by scientifically analyzing the facts of a case and shedding light on problems insurmountable to the official police force.

Sherlock Holmes Becomes a Sensation — and a Curse

“A Study in Scarlet” didn’t make major waves at the time of publication, but it did well enough to allow Doyle to sell his second Holmes novel, “The Sign of Four.” But it wasn’t until the format of his stories went from serially published novels to single-serve short stories that the popularity of his characters exploded. The Sherlock Holmes short stories became the must-see TV of the day, and the public appetite for this abrasive, drug-addicted detective and his long suffering friend and sometimes roommate, Watson, was insatiable.

But Doyle quickly found himself locked in a pair of golden handcuffs: He now earned enough money to abandon his medical practice, but it was at the cost of having to write stories about characters he really didn’t want to write about. As early as 1891, he was plotting various ways to kill Holmes off so he could focus on his other work, but the paychecks were difficult to resist. Drastically raising his rates to discourage publishers from the Holmes stories did nothing to cool demand, and he became one of the highest-paid writers of his time.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Killing Sherlock Holmes

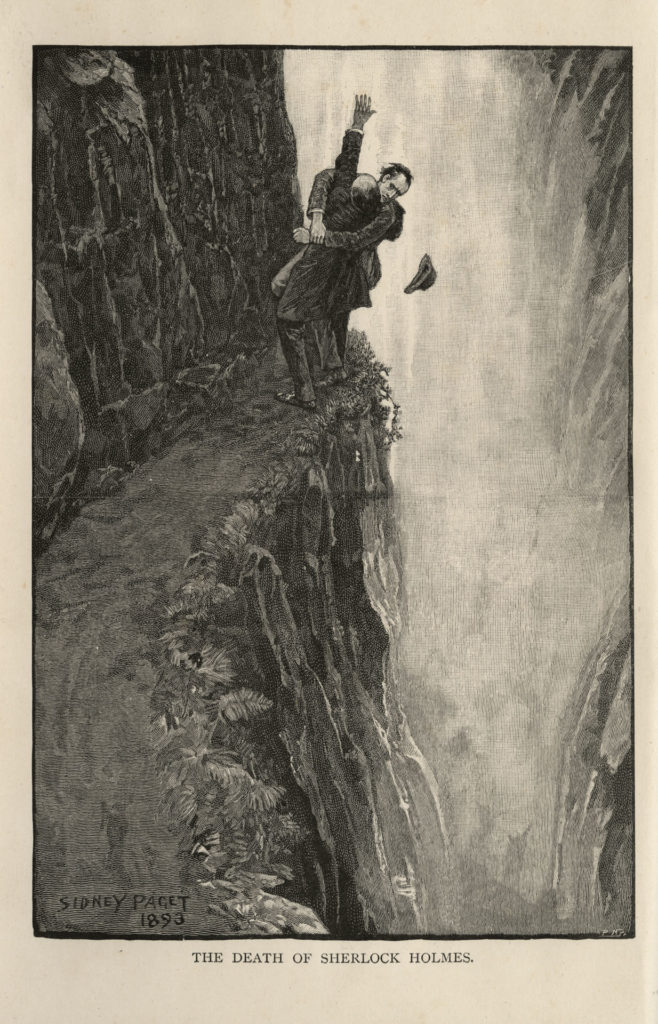

Doyle published 24 short stories in The Strand Magazine between 1892 and 1893 before deciding he couldn’t stomach it any longer. He sent Holmes tumbling off the side of a waterfall while locked in combat with hastily written archnemesis Prof. James Moriarty.

To say that the public reaction was bad would be an understatement. Hate mail poured in, Doyle was verbally abused, and tens of thousands of readers canceled their subscriptions to The Strand Magazine. Sherlock Holmes fans were intense, and they weren’t about to let this outrage stand unchallenged: Readers formed groups like Let’s Keep Holmes Alive, demanding that Doyle reverse his decision.

Activism of this kind was previously unheard of. Until this moment, audiences generally accepted whatever fictional event happened in their medium of choice and moved on. When Holmes died, though, his fans took it personally, and their gatherings, protests and letter-writing campaigns were some of the earliest examples of what we now know and recognize as fandom.

Doyle was understandably shocked, but he stood his ground for nearly a decade. Finally, in 1902, after nine years of pressure from his publishers and the public, while remaining careful to let people know Holmes was still dead, Doyle published “The Hound of the Baskervilles” as a sort of prequel, with the events of the novel having occurred in the years prior to Holmes’ death.

Doyle had known selling the story as a Holmes novel would guarantee its success, but it also ended up reminding him how much money was to be made off of Sherlock Holmes. One year later, after negotiating a fat paycheck to bring his character back for real this time, Doyle published “The Adventure of the Empty House,” revealing that Holmes had faked his own death and was now back in London, ready to pick up again with Dr. Watson (whose wife had conveniently died while Holmes was away). Once again ensconced in their lodgings at Baker Street, Holmes and Watson continued to consult and detect and bring order to London and beyond until the last Sherlock Holmes case penned by Doyle, “His Last Bow,” was published in 1917, featuring a retired Holmes on an undercover spy mission against the Germans.

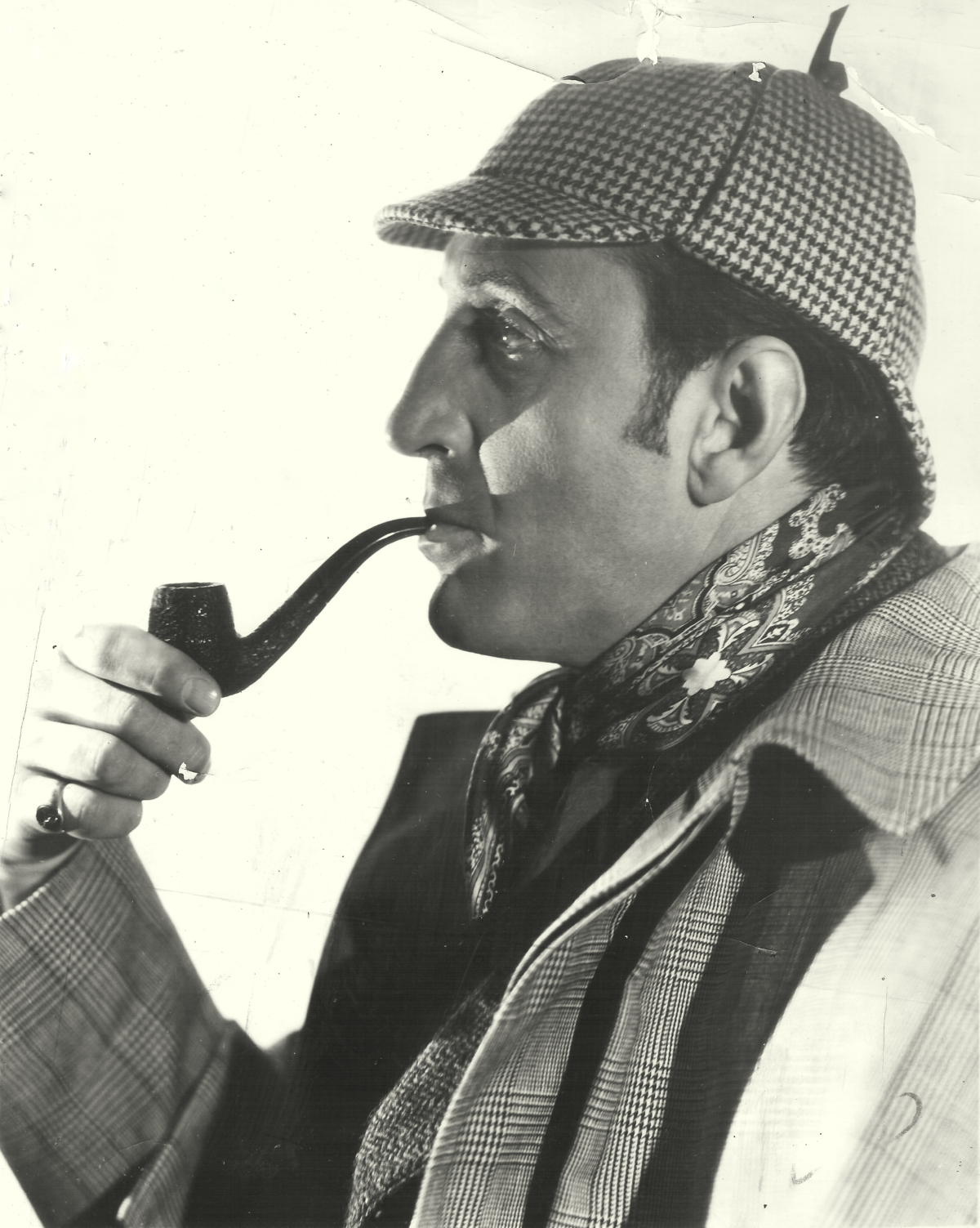

Sherlock Takes the Stage — and Adopts That Cap and Pipe

Happening in parallel to the Holmes stories Doyle was publishing were the first Sherlock Holmes stage productions, which started around 1893.

One actor in particular had a huge influence on the character and his future portrayals, and introduced many of the Holmes tropes we have all come to recognize. American actor William Gillette’s career as a star of the stage was already well established, but it was his portrayal of Sherlock Holmes for which he is the most well-known.

Doyle never mentioned a deerstalker cap in the stories, for example, but Holmes was depicted wearing one in an early Sidney Paget illustration. The deerstalker was a flat cloth cap worn during country expeditions, which made it appropriate for the rural setting of the case Holmes was on in the story the illustration accompanied. Once it became part of William Gillette’s regular onstage costume, though, the deerstalker was always seen atop Holmes’ head whether he was in the country or in town.

And while Holmes enjoyed tobacco in many different forms, he never smoked from a curved calabash pipe. The calabash is now synonymous with Sherlock Holmes thanks to Gillette, who found it easier to speak his lines with a curved pipe rather than a straight stem.

You can watch William Gillette as Holmes in a film version of his stage play below. The film was recorded in 1916, but he dubbed his voice 20 years later, when Gillette was 83.

But why change Doyle’s written word? Holmes spent most of his time in the stories rather unremarkably dressed: either in suits or, when circumstances required him to go undercover, in an appropriate disguise. The fashions he is most commonly known for today were either setting-specific, like the deerstalker and Inverness cape, or related to the time of day or night, like the dressing gowns.

But when you’re taking a character from the page to a stage, it’s natural to empasize the more visually interesting components of the source material. A brilliant consulting detective in a suit is all very well and good, but a brilliant consulting detective in a suit with a gorgeous, silky, quilted, purple dressing gown on top of it? Now we’re talking! Give him a few additional props like a magnifying glass and a violin and a hypodermic syringe and you’ve got the makings of an instantly recognizable character based on the accoutrement alone.

Gillette first brought Holmes to the stage in 1899 with a play creatively titled “Sherlock Holmes” that he’d co-written with Doyle, who once again was in need of money. It was a rehash of the plot points of several previous stories, with original characters and content provided by Gillette. He introduced a love interest for Holmes named Alice Faulkner, and gave the unnamed pageboy previously mentioned in a story a name (Billy) and a larger role. In a nice bit of reciprocity, Doyle stuck with the name Billy when the page boy appeared in subsequent stories.

More figures from the History of literature and film

Doyle Ignores Sherlock Holmes for Fairies

The distaste Doyle had for Holmes was always an interesting dynamic. On the one hand, his detective allowed him to live a very comfortable life, free to pursue his highly varied passions. But his lack of appreciation for his own characters in favor of what he felt were more serious efforts were probably his biggest blind spot. Holmes the logician certainly represented some aspects of Doyle’s own character, but there was one area in particular where the divide between man and creation could not have been greater: Sherlock Holmes outright dismissed the possibility of the supernatural, while Doyle was a devout spiritualist.

His interest in the supernatural started early, as he was already giving spiritualist lectures by 1917. But his obsession started to grow after a number of family tragedies. His son Kingsley died in 1918, his younger brother Innes a year later in 1919, followed by his mother in 1920 and two sisters in 1924 and 1927. Doyle not only hoped to communicate with his dead loved ones, he also wanted to prove to the world that there was more to it than what the eye could see.

“This agency stands flat-footed upon the ground, and there it must remain,” Holmes said in ‘The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire.’ “The world is big enough for us. No ghosts need apply.”

His spiritually minded creator, on the other hand, was taken in by fake photographs of fairies in a garden. In 1922, he even wrote an earnest book about the supposed proof of the supernatural, “The Coming of the Fairies.” The elfin creatures, however, were simply cutouts from children’s magazines. The creator of literature’s greatest detective had been hoodwinked by bored girls — one of them only 9.

Sherlock Holmes Goes to the Movies

The late 1800s saw the birth of film as a new medium, and it took little time for Sherlock Holmes to make his first motion picture appearance. The 1900 film “Sherlock Holmes Baffled,” a 30-second drama, features a recognizable Holmes in a dressing gown and smoking a cigar, being robbed by a mysterious, disappearing burglar.

Watch Sherlock Holmes’s first film appearance for yourself here:

Several other motion pictures of varying quality were released in the 1900s. Would you be surprised to learn that the canon Sherlock Holmes never said, “Elementary, my dear Watson”? The credit for that quote goes to Clive Brook from an early talkie. But it wasn’t until Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce made their debut in the 1939 adaptation of “The Hound of the Baskervilles” that film finally had its first iconic Holmes. And while Basil Rathbone gave us a highly respectable if campy Holmes, Nigel Bruce introduced the world to Dr Watson: Certified Clown.

The damage that Bruce’s Watson did to the reputation of the poor doctor was both profound and long-lasting. As the portrayal seen in the most popular Holmes films of the day, Bruce became the definitive Watson to the generations that were introduced to the character for the first time through those films. For a long time after that, Watsons veered strongly toward dimwitted comic relief rather than capable sidekicks.

To followers of the literary Holmes, the idea that a man as intelligent and short-tempered as Holmes would willingly suffer the foolishness of a man as incompetent as Bruce’s Watson is unimaginable. While Watson is no Holmes, the strengths he brought to their partnership were considerable: Watson’s medical experience, military service, loyalty and bravery made him a welcome and necessary companion. He was also crucially a much better shot with a gun than Holmes, so he could be relied on for backup during their more dangerous outings.

The Nigel Bruce portrayal started an unfortunate trend that now seems to have run its course. More recent adaptations have restored Watson back to a place of respectability, with Martin Freeman, Jude Law and Lucy Liu all doing much to make amends.

Watch Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce’s first turns as Holmes and Watson in the full version of “The Hound of the Baskervilles” here:

Small-Screen Sherlock Holmes

In the realm of serial television, the detective story makes for interesting, entertaining and predictable storytelling highly suitable for an hour-length program. A new mystery introduced once a week keeps the plot fresh, and the audience doesn’t need to have watched every prior episode to come in and quickly understand what’s going on and follow along. And every television detective still owes something to Holmes. Some are more obvious with their homage than others (House and Wilson from “House” being a prime example), but there are very recognizable Sherlockian traits to be seen in characters as varied as Adrian Monk, Gil Grissom and John Luther, to name just a few.

Are Sherlock Holmes Real Detective Stories?

So why has Holmes endured? It’s been argued that the original tales aren’t even real detective stories, since they fail to give the reader the information required to solve them independently. Later detective stories, like those featuring Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot, have delved much deeper into the clues, details and complex plots surrounding their respective mysteries than the Sherlock Holmes canon ever did.

Perhaps it’s more accurate to think of Doyle’s work as adventures rather than whodunits. The Sherlock Holmes canon is more about the friendship between Holmes and Watson, an ongoing character study of the two men and the incredible circumstances they find themselves in. The stories lend themselves to endless re-reading despite you knowing how the mysteries unravel, and they delight the reader not with the thrill of how it ends but the journey along the way. Doyle may have grown to hate the character, but there are frequent moments of artistry and delight to be found within these pages. There is also something very comforting in knowing that no matter how tangled your problem might be or how dark the current situation might seem, there is a man out there with the singular power to shed light where it’s most needed and restore order from chaos (“Sherlock Holmes Baffled” notwithstanding).

Modern Sherlock Holmes Fandom

Holmes fans haven’t gone away, either, if anything they’re more fanatical than they were since the early days of organized harassment of Doyle. Arguably one of the best-known fan societies is the Baker Street Irregulars, founded in 1934, which is still going strong with regular meetings, publications and events. New societies and more informal groups continue to form regularly, whether in person or online, and every depiction of Holmes and Watson builds a brand-new on-ramp for a nascent fan to fall in love with the characters and seek out like-minded enthusiasts.

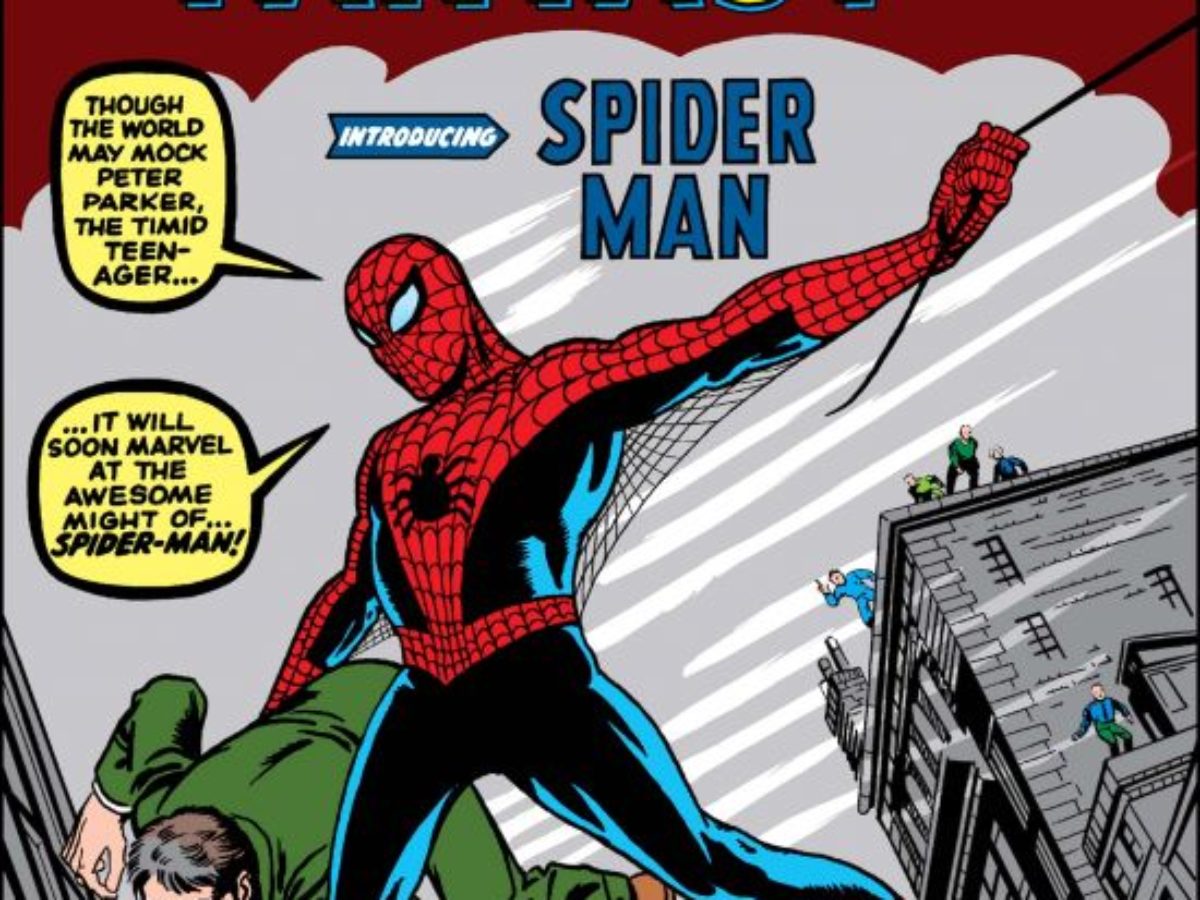

The characters have also proven themselves to be extremely adaptable, and because of this Holmes is the most portrayed fictional character of all time. The mention of Sherlock Holmes initially conjures up images of gaslight and hansom cabs, but the adventures themselves took place over a long period of time when the world was rapidly changing. Telephones, gramophones, submarines and automobiles all made their appearance while Holmes was still active, and he was able to seamlessly incorporate the possibilities of every new technology into his own skill set. A modern-day Sherlock Holmes would know his way around the internet and a smartphone just as well as the original would have made use of his magnifying glass, and as we have all seen firsthand, just because information is accessible doesn’t mean you don’t need a sharp mind to sift through that all that data and draw the correct conclusions from it.

Holmes has always been a man that is in touch with the times, and as criminals evolve, he’s still going to be hot on their trails.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.