This political commissar’s report, dispatched in the spring of 1953 to the League for the Independence of Vietnam, commonly known as the Vietminh, was one of many expressing concerns about a little-known French-led insurgency against Ho Chi Minh’s communist movement. During the latter stages of the 1946–54 First Indochina War such shadow warriors were part of the Composite Intervention Group (Groupement mixtes d’intervention, or GMI), originally known as the Composite Airborne Commando Group (Groupement de commandos mixtes aéroportés, or GCMA). The GCMA/GMI ultimately organized some 20,000 partisans to conduct covert operations inside territory long considered secure by the Vietminh. Some historians have questioned their effectiveness, but the guerrillas harassed their opponents and forced them to commit thousands of frontline troops to protect their supply lines and bases.

The French army’s humiliating 1940 defeat by the German Wehrmacht shattered the illusion of Franco invincibility and sparked a resurgence of nationalistic movements in its Asian colonies. Japan’s early victories in the Pacific added momentum. When the Japanese army marched into Indochina after the fall of France, its soldiers were not greeted as liberators but as yet another batch of foreigners intent on expropriating the region’s resources and oppressing its people. Japan’s heavy-handed policies prompted Ho Chi Minh to return to Vietnam in 1941 and join the struggle for independence. Although he had spent his adult life abroad, Ho was an ardent nationalist determined to oust both the Japanese and the French. He was also a committed Marxist. Despite the latter fact, in early 1945 personnel of the American Office of Strategic Services (a predecessor of the CIA) joined him in the fight against the Japanese.

At the July 17–August 2, 1945, Potsdam Conference, held two weeks after war’s end in Europe, Japan’s imminent surrender was among the many issues addressed by the United States, Great Britain and the Soviet Union. Nationalist China was assigned responsibility for disarming the Japanese north of Vietnam’s 16th parallel, while Britain was given the task below that line. Allied leaders at Potsdam purposely ignored the French, who were eager to restore their hegemony in Indochina. France was neither invited to the conference nor consulted, a source of great irritation for General Charles de Gaulle, chairman of the provisional government. It was one of many real or perceived slights that grated on Gallic sensitivities throughout World War II and in its aftermath.

On Sept. 2, 1945, as representatives of Japan’s Emperor Hirohito signed the Instrument of Surrender aboard the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay, Ho Chi Minh unilaterally declared his country’s independence, naming it the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV). A huge crowd in Hanoi heard his speech, in which he quoted the U.S. Declaration of Independence and French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, drawing parallels to the condition of his people under French rule.

Ho realized only the United States could thwart the postwar re-establishment of French Indochina, so he petitioned the administration of President Harry S. Truman for recognition of the DRV. But U.S. antipathy toward Ho’s embrace of Marxism overrode empathy for the exploited Vietnamese, and the Americans ignored his appeal. With World War II concluded, Truman considered France an essential partner in the recovery of Europe and prevention of Soviet expansionism. Consequently, officials in Washington grudgingly tolerated French imperial ambitions.

By the time British troops landed in southern Vietnam to accept the Japanese surrender, Ho’s Vietminh revolutionaries had taken over the city government in Saigon and most other cities and villages nationwide. As the vanguard of the 20th Indian Division disembarked in mid-September 1945, it was confronted by a dangerous insurrection. Britain, struggling to maintain its own empire, supported returning Indochina to French sovereignty and appealed for military assistance to quell the chaos. In early October a contingent under General Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque, who had led the Free French into Paris in August 1944, arrived and helped subdue the rebellion. Once order was restored in Saigon, Leclerc expanded French influence into the surrounding countryside, handing the revolution a major setback.

China had a firmer grip above the 16th parallel and prohibited the French from returning. Almost immediately emissaries from Paris began secret talks with Chiang Kai-shek’s ministers. In March 1946, after France dropped all claims to its concessions on the Chinese mainland, the French Far East Expeditionary Corps (Corps expéditionnaire français en extreme-orient, or CEFEO) was allowed to occupy Hanoi. Ho Chi Minh bristled at the force’s presence but knew his militias were not ready to take on the CEFEO; he sought to buy time by traveling to France for negotiations he hoped would at least lead to dominion status with the newly created French Union of overseas territories.

Discounting the rising tide of nationalism sweeping Asia and Africa, intransigent French Foreign Ministry representatives had no intention of allowing increased Vietnamese autonomy. After three months of being stonewalled, a discouraged Ho returned home amid building tensions. That December as full-scale hostilities erupted between the Vietminh and the CEFEO, Ho was forced into hiding and began his protracted political and military struggle.

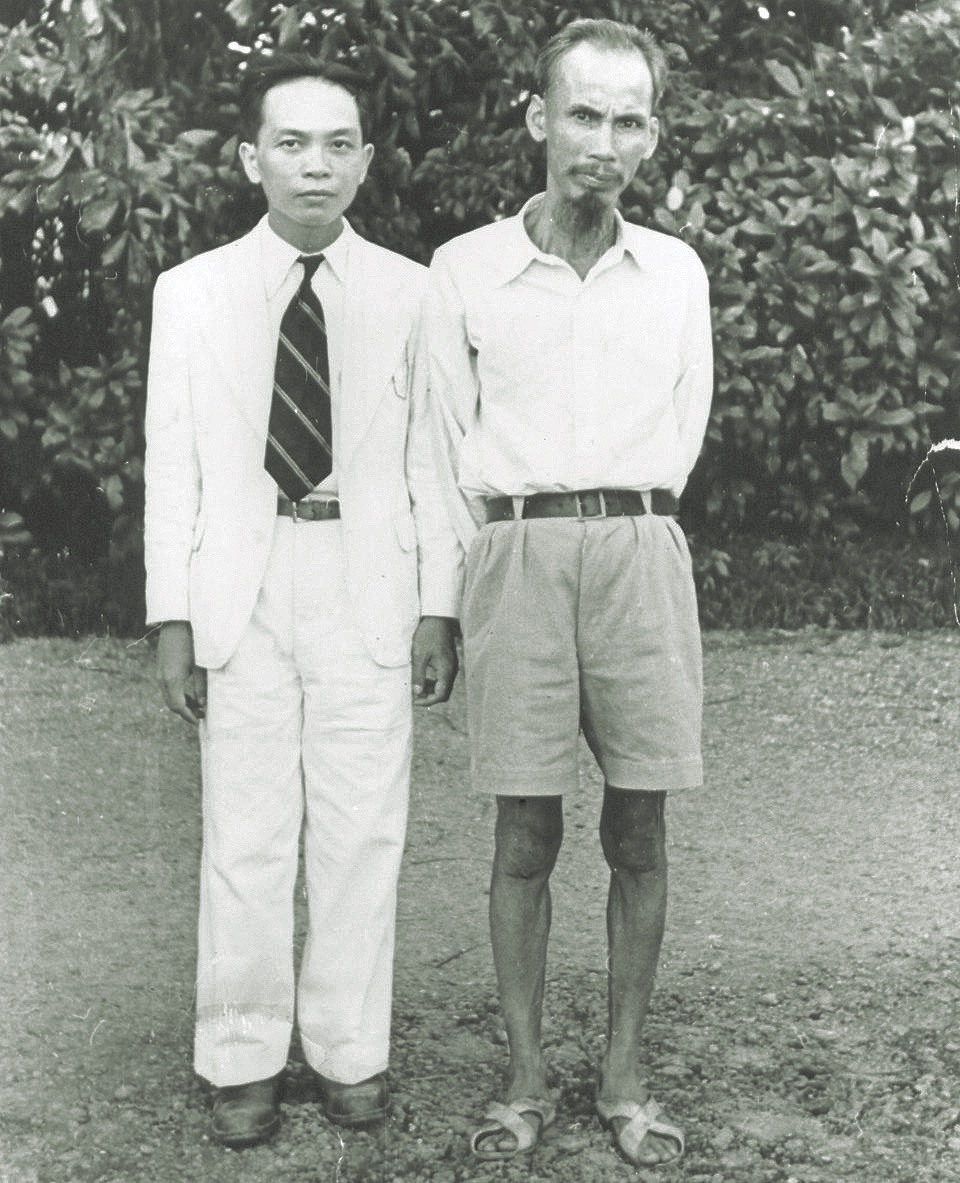

The CEFEO, initially comprising less than two divisions, was ill-prepared for the hit-and-run warfare waged by the Vietminh. Looking to defeat the enemy in large set-piece battles, the French launched a series of attacks, often combining infantry, armor and airborne assaults. The French managed to seize vast tracts of jungle north of Hanoi, but the enemy refused to engage in decisive action. General Vo Nguyen Giap, Ho’s military commander, set the tempo of combat as he continued to build and train his army. When the time was right, he attacked and withdrew before the CEFEO could bring in reinforcements.

Preoccupation with luring Giap into a major engagement consumed the French army, whose brass didn’t think to employ disaffected segments of the population against the Vietminh, even though colonial administrators had cultivated good relations with the country’s minorities. Some of the Tai and Nung tribes in the northern mountains believed France would support their pursuit of a semiautonomous federation, while the Montagnards of the Central Highlands sought protection from the Vietnamese, their traditional lowland enemies.

The French approach in Indochina changed in 1950 when General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, an experienced veteran of both world wars, took charge. The general questioned why no attempt had been made to organize partisans among the friendly minorities, insisting they represented a potentially valuable intelligence source, able to harass the enemy and counter communist influence in the hinterlands. De Lattre wanted guerrillas to threaten Vietminh rear areas and then evolve into mobile strike forces, complementing the army’s offensives. His vision came to fruition in April 1951 when the GCMA was created as a joint effort between the French civil and military intelligence services. Tragically, just as the initiative was taking root, 62-year-old de Lattre was medically evacuated to France, where he died of cancer on Jan. 11, 1952.

GCMA success was dependent on recruiting officers and NCOs who could speak tribal languages, understood local customs and had the psychological endurance necessary to withstand long periods of isolation. The first volunteers were “old Indochina hands,” unconcerned about being out of the army’s mainstream. Their bosses were glad to release them, as they were natural loners, more comfortable in a solitary environment than in colonial parachute battalions. Some of their colleagues said the men had “gone native,” a pejorative assessment.

Organizing the Tai and Nungs was the first priority, as they would make an immediate contribution up north, where the Vietminh were the strongest. Once a potential guerrilla group was identified, a two-man GCMA team parachuted into the area to parlay with the elders. If they were receptive, additional supplies and personnel were sent to equip and instruct new recruits, a process typically taking six months. The objective was to form a battalion of 300–400 men commanded by a French officer and assisted by a few NCOs. As soon as the first units were operational, Montagnard clans near Pleiku and Kontum began training.

Almost immediately intelligence on enemy activity improved. As the guerrillas became more competent, missions changed to direct combat, at first focused on low-risk tactics such as mining roads and destroying unguarded caches. Some of the fighters reached a level of proficiency that allowed them to gnaw at the Vietminh with ambushes and raids. Their impact was evident in an intercepted 1953 message:

We need to exterminate at all cost the pirates [GCMA]. Their work can be considered as the biggest machination destined to undermine the Vietminh movement. Their work will necessitate our re-education of affected populations and the reconstruction of our bases.

Military exigencies occasionally necessitated use of the GCMA in conventional roles. In one October 1953 operation two battalions of Tai tribesmen attacked the communist stronghold in the twin cities of Coc Leu and Lao Cai, along the Chinese border, part of a raid synchronized with a French airborne assault on the base. After overrunning the objective and killing 150 enemy troops, the guerrillas led their airborne counterparts into the jungle, handing off the paratroopers to other friendlies who took them to an evacuation airfield.

In May 1953 Major Roger Trinquier, who related his experiences in Indochina and Algeria in the widely acclaimed treatise Modern Warfare: A French View of Counterinsurgency, was appointed to lead the GCMA. Trinquier’s relatively junior rank belied the scope of his responsibilities as he set about reorganizing his new command. An experienced GCMA leader, he believed groups of 1,000 partisans assisted by collaborating locals were more effective than smaller bands. He reinforced the northern region with such 1,000-man units, confronting the communists with correspondingly greater firepower.

Trinquier sought to limit the role of volunteers to organizing and training, placing less emphasis on leading in the field. Regardless of how well French soldiers identified with their charges, life among the tribes in primitive conditions was difficult, and the specter of being seriously wounded was a death warrant. The presence of Europeans also put the population at grave risk, subjecting villagers to severe retaliation when the Vietminh made sweeps through the region. Absent the Europeans, the guerrillas were able to blend in with the local people scratching an existence out of the hill country. Still, some tribesmen lacked the expertise to operate independently, requiring seasoned French officers to remain in the bush with their troops. One lone corporal using the pseudonym René Riesen spent several years in the Central Highlands, commanding 1,000 Montagnards and even intermarrying into the tribe. He was awarded the Croix de guerre for his actions and wrote a 1955 memoir of his experiences. The following year Riesen was killed in action in Algeria.

When General Henri Navarre arrived in the spring of 1953 to take command in Indochina, he allocated more resources to the GCMA but was upset that multiple agencies were running covert operations. French intelligence had formed its own militias, organizing religious sects along the Cambodian border and even the notorious Saigon gangsters Binh Xuyen. Freelancing intelligence operatives were only one of Navarre’s problems. Some of his subordinates had an inherent distaste for what they perceived as cloak-and-dagger work and tried to undermine the GCMA by shifting its supplies to the regular army. He soon replaced the naysayers and put all unconventional units under a single headquarters, renaming it the GMI. Roger Trinquier was promoted to lieutenant colonel and given command.

But the war was changing, the tempo escalating. Giap now commanded a proficient army organized into regiments and divisions, equipped with heavy weapons supplied by the Peoples’ Republic of China and supported by a legion of porters. Giap’s army was about to give the war a new face, as it was finally ready to fight on French terms. Trinquier recognized this evolution and directed attacks on the enemy’s sustainment capability, not main force units. GMI fighters were ordered to interdict the enemy’s logistical lines but faced fierce opposition from the Vietminh infantry assigned to protect them. High casualties incurred by the partisans were omens of things to come.

The pitched battle the French had long sought was about to break out in the northeast corner of Vietnam. Yet the place, Dien Bien Phu, was in an isolated valley near the Laotian border, too far from Hanoi and Haiphong to be adequately supported by an air bridge subjected to heavy enemy fire. Although the French air force was augmented with U.S. transport aircraft—Fairchild C-119 Flying Boxcars flown by American civilian pilots—aviation assets were too meager to resupply the garrison, which never exceeded 15,000. Planners grossly miscalculated Giap’s ability to mass superior numbers of ground troops, sustain large formations, organize lethal anti-aircraft defenses and assemble enough artillery to outgun his opponent. Once the Vietminh initiated their major offensive on March 13, 1954, the outcome was preordained. Capitulation on May 7, after 56 days of intense fighting, sounded the death knell for French rule in Indochina.

Switzerland had convened a multilateral conference in Geneva on April 26 to resolve various Cold War issues, but the fall of Dien Bien Phu focused deliberations on Indochina and factored largely in an agreement signed on July 20. With hostilities ended, Laos and Cambodia were recognized as independent countries, and Vietnam was partitioned along the 17th parallel. Believing the military balance was in his favor, Ho Chi Minh was infuriated by the creation of two Vietnams—the DRV in the north and an independent state in the south—but he was pressured to accept it by his Soviet and PRC allies, who feared U.S. intervention were the war to continue.

The ink on the Geneva Accords was hardly dry when Giap’s army launched major attacks against northern anti-communist guerrillas. Trinquier wrote a report decrying the situation:

The total suppression of logistical support…will bring in its wake the progressive liquidation of our elements. There is little hope of seeing the leaders of our maquis [a French term for guerrilla fighters] escape the “clemency” of President Ho Chi Minh. As of Aug. 15, 1954, 15 enemy regular battalions, 15 regional battalions and 17 regional companies are now committed against them. Ceasing operations as per orders [Article 11 of the Geneva Accords]…our maquis, undeafeated on the field of battle, have been offered up for sacrifice.

France turned its back on its GMI fighters, refusing to evacuate personnel who faced execution if captured by the Vietminh, as Navarre believed such action would violate the accords’ cease-fire provision. Trinquier, dumbfounded by Navarre’s disregard for his subordinates, appealed to his American colleagues to airdrop supplies to hard-pressed units. Since the United States was not a signatory to the Geneva Accords, he hoped the C-119 pilots who had flown missions over Dien Bien Phu would step into the vacuum created by French timidity. Notwithstanding their willingness, the U.S. government denied permission and ordered the aviators to leave Indochina.

Two years after the official end of the war a communist newspaper reported the killing of 183 and capture of 300 “enemy soldiers.” Guerrillas who had escaped the Vietminh pogroms hid their weapons and melted back into the population. A few hardcore French officers and NCOs stayed with their comrades and suffered the fate of those who continued to fight. From time to time their transmitted appeals for support crackled over the radio waves, but such traffic gradually faded into silence as the communists annihilated the last remnants of the GMI. Only one Frenchman managed to evade Giap’s hunters and make the long march south to freedom.

Military analysts acknowledged some of the GCMA/GMI’s tactical successes but rebuked the guerrillas for having failed to cut the 500-mile communist supply line running from China to Dien Bien Phu. Such analysts either discounted or were unaware General Giap had been forced to detach two more infantry regiments, part of his assault force, to provide increased protection for his logistical network. In a postwar report Giap stated, “In mid-March our army’s General Staff had to transfer its 9th Regiment…and detach our 176th Regiment from the campaign forces and send them to Lai Cau to sweep away the phi [a Vietminh term for “bandits”].” The general admitted Dien Bien Phu would have fallen sooner had those infantry units fought in the final offensive.

Bernard Fall, the author of Hell in a Very Small Place, a detailed account of Dien Bien Phu, was the most strident critic of the GMI’s failure to affect the outcome of the battle. But Fall, long touted as one of the keen observers of that war, overestimated the fighting capacity of the GMI and discounted the Vietminh’s commitment to their lifeline. Large-scale interdictions were far beyond the capability of lightly armed paramilitary troops, who were no match for veteran soldiers tasked with protecting their porters. In 1969 U.S.-led covert actions on the Ho Chi Minh Trail further proved that hit-and-run raids did not hinder the enemy’s supply route for any appreciable period.

Time has not changed the paradigm that guerrillas cannot fight toe-to-toe against determined, well-trained army units. They must be used in supplementary roles—e.g., harassing, attacking sparsely defended targets and shoring up support among the people. Realistic missions are the sine qua non of successful unconventional operations. Roger Trinquier recognized as much, even if his detractors, though beneficiaries of 20/20 hindsight, did not.

John Howard served in the U.S. Army for 28-plus years, retiring as a brigadier general. He spent two tours in Vietnam (1965–66 and 1972–73) as a combat infantryman. For further reading he recommends Street Without Joy, by Bernard B. Fall, and A War of Logistics, by Charles R. Shrader.