It was called the Snowball Route—officially the North Atlantic Ferry Route—from Goose Bay, Labrador, to the one-way runway at Bluie West One on Greenland; then across to Keflavik, Iceland, to refuel again; on to Prestwick, Scotland; and finally to England: the UK’s World War II aerial lifeline, flown by freighters as well as ETO-bound bombers and fighters. Route briefings sometimes consisted of showing 200-hour pilots photos of the Greenland coast and fjords. There weren’t many Arctic experts available, other than those aboard the U.S. Coast Guard’s Greenland Patrol cutters and some under the command of Colonel Bernt Balchen, the famous polar explorer stationed on Greenland to establish air bases and oversee search-and-rescue and weather station resupply missions.

On November 5, 1942, a Douglas C-53, a paratroop-outfitted version of the C-47, was Snowballing westbound, empty except for its crew of two plus three military passengers returning to the U.S. from Scotland. The Skytrooper never made it, the crew radioing that they’d made a forced landing on the Greenland ice cap and giving an approximate position. The airplane was intact, and apparently there were no injuries.

ONE AIRPLANE DOWN

The next two nights, flares fired by the C-53 crew were seen at a weather station on the Greenland coast, and rescuers set out toward them on motorized sleds. They’d be back in three or four days if the weather held, the rescuers guessed. But their sleds broke down, and they never found the C-53. The flares were the last that would ever be seen or heard of that airplane and its crew.

Recommended for you

Meanwhile, a variety of eastbound B-17s, B-25s and C-47s that were either already over Greenland or gassing up at Narsarsuaq—the famous Bluie West One base—were detoured for search duty. One of them was a B-17F originally bound for England. On November 9 it took off from BW-1, assigned to search the area where the C-53’s flares had last been seen. Aboard the Flying Fortress were its original six-man ferrying crew, an Army enlisted man they’d picked up at Goose Bay and two volunteer observers who had jumped aboard at BW-1. They would live to regret their Samaritan offer.

The B-17 reached its search area and ran into a bank of low clouds. The pilot, Lieutenant Armand Monteverde, did a 180 around the weather and headed back into the search grid, only to fly into a sudden whiteout. Sky, cloud and ice were the shadowless same. There was no horizon. Monteverde did the only thing he could and banked away to fly back to clearer air. But the B-17’s left wingtip caught the ground, and the airplane skidded onto the ice cap. It was a hard crash, with the bomber traveling only about 200 yards before splitting apart just aft of the wings.

The Fortress had come down atop an active glacier, spider-webbed with crevasses, like landing in the middle of a minefield. The entire broken-off tail section hung over a large open chasm, with another maw yawning just in front of the bomber. One crewman suffered a broken arm, and others had bad cuts and bruises. Just four were unhurt.

NOW THERE WERE TWO AIRPLANES ON THE ICE

Meanwhile, an RAF Douglas Havoc out of Gander, being ferried through a snowstorm by a Canadian crew, flew past its refueling stop at Narsarsuaq and put down on the ice before it tanks ran totally dry.

THREE AIRPLANES

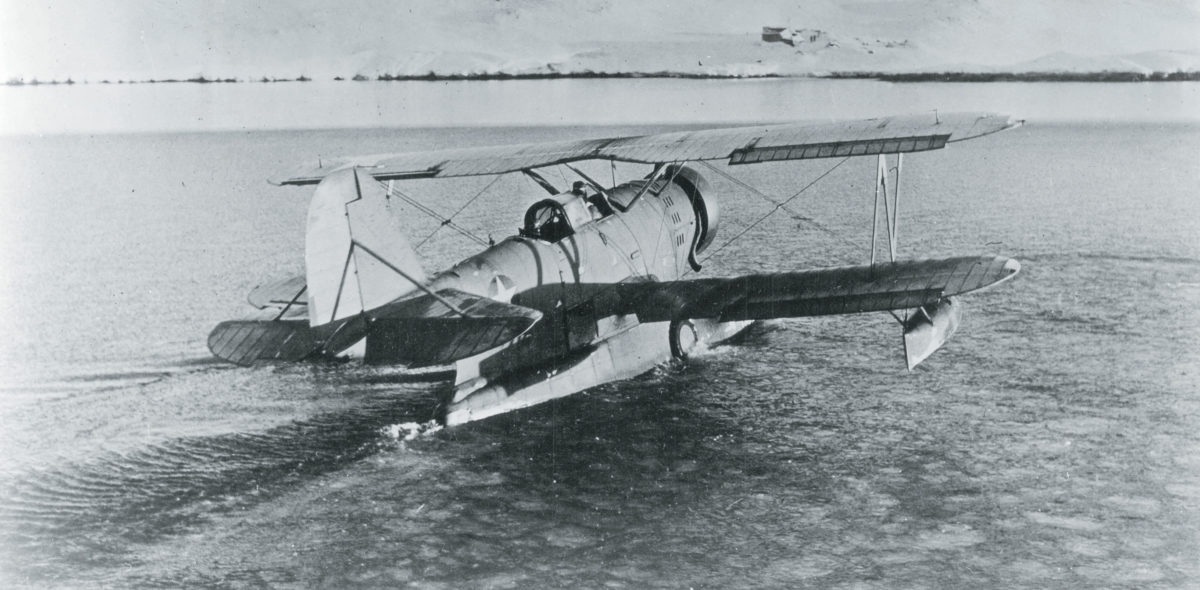

The Canadians set out on foot for the coast. On November 18, a search plane out of BW-1 spotted the Havoc, but its crew was gone. Five days later, a Grumman J2F-4 Duck from the Coast Guard cutter Northland, hove to in a bay on the southeast coast of Greenland, found the crew’s trail, trod by snowshoes they’d fabricated from pieces stripped from the Havoc. That night, Northland fired off flares, and the Havoc crew spotted them. One of the pilots responded by setting fire to his coat, which in Greenland in late November is a good approximation of burning your bridges. Fortunately, the blazing parka was spotted by crewman aboard Northland, which put a rescue party ashore and found the Havoc crew.

The downed B-17’s radioman, Corporal Loren Howarth, had gotten the airplane’s radios working and was in touch with a nearby weather-rescue station. Sixteen airplanes were sent out to search for it—15 military ships from Bluie West One and a TWA Douglas DC-4 from Bluie West Eight at Sondre Strom Fjord. BW-8 was Bernt Balchen’s base. Just north of the Arctic Circle, it was already pretty much wintered in, and the civilian Doug was the only airplane on the ramp.

After five days of unflyable weather, Balchen himself finally discovered the B-17 while flying the TWA airliner. The same motorsled rescuers who had broken down while trying to find the original rescue target, the C-53, now headed for the B-17, accompanied by an experienced Norwegian dogsledder and his team.

Balchen ordered the cutter Northland’s J2F-4 into the hunt as well. On the morning of November 28, the Duck was hoisted over the side, and Coast Guard pilot Lieutenant John Pritchard Jr. and his radioman, Petty Officer 1st Class Benjamin Bottoms, took off for the B-17 crash site.

Pritchard overflew the B-17 and radioed its crew for landing advice. “Don’t try it,” Corporal Howarth replied, “crevasses everywhere.” Colonel Balchen, coincidentally, was overhead at that moment in the DC-4, making a supply drop.

Pritchard found a smooth, sloped, apparently crevasse-free area a mile north of the B-17 and carefully touched down with his landing gear extended. He landed uphill, and the Duck quickly came to a stop—the very first successful landing of an airplane on the surface of Greenland’s ice cap. (A PBY copiloted by Balchen had landed on a temporary ice cap lake on an earlier occasion, so the distinction is a fine one.)

Pritchard and Bottoms hiked to the B-17, whose commander assigned two walking wounded to return to the Duck and fly out. Pritchard decided to make the takeoff gear up, using the central pontoon as a big ski. That required shoveling the snow from under the main-gear tires until the Duck was resting on its keel, to release the weight on the downlocks so the gear could be cranked up manually. The takeoff was made downhill, and the Duck headed back to Northland. It was nearly dark when the amphibian arrived, so it was hoisted back aboard.

By this time the motorsled rescuers were also approaching the B-17. (The Norwegian dogsled team had been forced to quit the search.) The sledders camped for the night outside the area of crevasses, and it looked like a plan was coming together, with Pritchard due back the next morning. Balchen returned to BW-8 confident that the rescue of the seven remaining B-17 crewmen was imminent.

On the morning of November 29, Pritchard lightened the Duck as much as he could, tossing off all extraneous gear. He and Bottoms planned to make two trips that day, snatching to safety more B-17 crewmen. Soon after they took off, however, the weather rapidly worsened. The cutter radioed to its Duck, ordering it back to the ship. Pritchard and Bottoms never heard the recall—or perhaps ignored it.

This time Pritchard landed on the ice cap intentionally gear up, sliding to a stop on the airplane’s pontoon. As he was touching down, the Army sledders were approaching the B-17. Only one made it. The other plunged into a crevasse, its driver never to be seen again. To make matters worse, fog was rolling in. Lieutenant Monteverde sent radioman Howarth to the Duck’s landing site to tell Pritchard to get the hell out while he had a chance. Howarth joined the Duck’s crew for the trip back to Northland.

Howarth’s decision proved fatal. The Grumman crashed in a snowstorm en route back to the cutter, killing all three aboard.

FOUR AIRPLANES DOWN

The B-17 crew had been on the ice for 20 days by that time. The men were sheltering in the broken-off tail section, occasionally resupplied by air when weather permitted, but they were cold, hungry and increasingly frostbitten. Now the tail was in danger of sliding into the chasm over which it was perched, so they cut it loose and moved to a snow shelter they’d built under the right wing. Little did they know that their discomfort would continue for another five months, though they were just 29 miles from a U.S. Army Air Forces weather-rescue facility called Beach Head Station.

An attempt was made to carry the most seriously frostbitten crewman to the station on the surviving motorsled. A mile from the B-17, an ice bridge collapsed and one of the four sledders disappeared into the void. The three survivors continued on another six miles before the sled engine died and they were forced to make camp. Those men would be rescued, but not until two months later, despite the fact that numerous motor-and dogsled expeditions tried to reach them.

In mid-December, the Army Air Forces hired an unusual Canada-based ski-plane, a Barkley-Grow T8P-1, for another attempt to reach the B-17. Built by a short-lived Detroit company that eventually became part of Vultee, the T8P-1 looked like a large fixed-gear Twin Beech. The down-and-welded wheels made transitions to either floats or skis simple. Eastbound from BW-1 to the Bluie East Two base three days before Christmas, the Barkley’s Canadian bush pilot encountered a stiff headwind and ran out of gas. He put the twin down on the ice of a fjord in whiteout conditions, landing heavily and wrecking the airplane. He and his navigator, both old Arctic hands, hiked out and found their way to an Inuit hunter village.

FIVE DOWN

Balchen decided he needed PBYs, the go-to bird when everything else has failed. He figured he’d belly-land a Cat near the B-17, just as Pritchard had with the Duck. But there were only four PBYs on Greenland, and they were desperately needed for convoy patrol duty, since German U-boats were then sinking Britain-bound freighters and troop transports pretty much at will. On January 4, 1943, the Navy finally agreed to provide two Catalinas as long as Balchen “directly supervised the landings.”

One day later, an AAF C-45 Twin Beech on skis that had been assigned to the rescue mission disappeared somewhere between BW-1 and BE-2.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

SIX

A second C-45 arrived at BE-2 on January 20 and was fitted with skis. It made one test flight and chopped off its ski tips with its props but managed to land safely.

Weather and other delays kept Balchen’s two PBYs grounded, though on January 27 a Coast Guard PBY not being “supervised” by Balchen cruised straight onto the ice cap in a whiteout about 50 miles from BW-1. The damage was slight, but the Cat had plugged itself into an area of ice ridges and hillocks where takeoff was impossible.

SEVEN AIRPLANES DOWN

On February 5, Balchen and his pilot made a successful PBY belly landing on the ice near the camp where survivors of the ice-bridge collapse had holed up. Balchen rescued the three men, but it wasn’t easy. One of them had already lost his feet to frostbite. Some reports say they had fallen off, others that they were later amputated. The Cat’s hull had frozen to the ice while the survivors were being loaded, and the crew had to rock the airplane by its wingtip floats until, engines wailing, it broke free. Then, as the PBY taxied in circles to keep from getting stuck again, one after another the crewmen jumped in through a waist blister.

Just three men remained in the B-17 wreck, barely sustained by airdrops. Balchen again landed in a PBY at the motorsled camp and dropped off a three-man rescue party with a dogsled and nine huskies. The sledders retrieved those last three survivors from the Fortress, though it took them three days to make the 12-mile round trip. Balchen returned on April 5, but the load was too much for his Catalina, which blew an engine while trying to get airborne. Temporary repairs were made, and the next day the PBY took off with only its crew aboard. Even Balchen remained behind, for he would lead the dogsled party off the ice cap to safety. They arrived at Beach Head Station on April 16.

The ordeal was finally over for the last members of the B-17 crew. Some of them had spent almost 5½ frigid months awaiting rescue, frequently battered by storms and screaming winter winds. The entire epic cost five rescue planes plus the C-53 and B-17 that were the original objects of the mission. Five men had died—three aboard the Coast Guard Duck and two in glacial crevasses. The Army Air Forces, Navy, Coast Guard, Air Transport Command, Royal Canadian Air Force and Norwegian Sledge Patrol had at one time or another been involved in the operation, and dozens of land rescue attempts were also made, most of them unsuccessful. It was one of the most extensive search-and-rescue operations ever attempted.

Was it worth it? We’d have to ask the B-17 crew, but we know what their answer would have been.

For further reading, Stephan Wilkinson suggests Frozen in Time, by Mitchell Zuckoff. Also see the article by Captain Donald M. Taub here.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Facebook @AviationHistory | Twitter @AviationHistMag