Although the Confederates had won the first major battle in the state of Virginia in July 1861, Union forces still controlled large areas of the Old Dominion in the summer of 1862 and were threatening the Confederacy’s capital at Richmond on two fronts Major General George B. McClellan had completed his drive up the Peninsula and was poised to strike the city by June, causing plenty of anxious moments for the Rebel high command. It also didn’t help that two of the three Confederate field officers holding the full rank of general—Joseph E. Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard—were at odds with President Jefferson Davis, who, as a West Pointer and former secretary of war, never hesitated to offer opinions on military affairs. Johnston believed he should be the South’s top general, and Beauregard constantly complained that Davis was stifling his initiative. The result was a lack of confidence and communication between the president and these two proud officers.

Davis’ alternatives were limited. His favorite general, Albert Sidney Johnston, had been killed a few months earlier at the Battle of Shiloh. Adjutant General Samuel Cooper was already serving in the role he was best suited for. Braxton Bragg, a friend of the president, was in the midst of conducting a difficult campaign in the West. Then there was Robert E. Lee, a respected Regular Army veteran who had been offered command of Union forces following Fort Sumter. He declined the post when his native Virginia seceded. After some unimpressive field commands in western Virginia in early 1861 and a brief tour of duty supervising southeastern coastal fortifications, Lee was recalled to Richmond to advise Davis on strategy. It was due to fortuitous timing, and more than a little luck, that Davis subsequently placed Lee in command of the Confederacy’s largest and most important army in June 1862.

By the end of May, McClellan had backed Joseph Johnston’s army to the outskirts of the capital, forcing him to launch a poorly executed attack on the Federals at Seven Pines (Fair Oaks) on May 31. When Johnston was seriously wounded riding the lines that night, it opened the door for Lee and his date with destiny. On June 1, Lee managed to disentangle the Rebel army from the mess at Seven Pines and then set about preparing for an offensive that would drive McClellan from the gates of Richmond. The series of clashes that would become known as the Seven Days’ battles had enough Confederate missteps that another Federal officer might have been able to turn the tide to the North’s advantage. But McClellan played right into Lee’s hands and helped ensure that “Marse” Robert would gain a lasting reputation as a brilliant commander.

In keeping with the spirit of this column, which encourages readers to visit and revisit theaters of war like central Virginia, we will not discuss the many actions in the area relevant to other Civil War campaigns. “In their Footsteps” will revisit this hallowed ground many more times in the future, just as every Civil War traveler should.

Beginning in Richmond, this tour will cover the Battles of Oak Grove, Beaver Dam Creek, Gaines’ Mill, Savage’s Station, White Oak Swamp, Glendale, Malvern Hill and related actions and sites. Although visitors can easily cover the ground in a single day, spreading this tour over two or more days will provide a much better experience. Outdoor activities on land and water can also enhance any trip. And if the heat and humidity become too much when visiting in the summer, great museums, shops and other indoor activities are plentiful in the culturally rich capital.

The Visitor Center for Richmond National Battlefield Park, on the grounds of the former Tredegar Iron Works at 470 Tredegar Street, is a good place to start. The center has exhibits, audiovisual programs, a schedule of living history and other events, and park interpreters to answer questions about the Seven Days’ battles and the defense of Richmond. From the Visitor Center proceed north to Broad Street, then east to 3215 E. Broad Street, site of the Chimborazo Medical Museum.

Named by a Richmond traveler after a volcano in Ecuador, Chimborazo Hill was home to one of the largest Confederate military hospitals. Construction of the facility started after Richmond was flooded with wounded soldiers from the First Battle of Manassas, and the hospital’s 75-plus wards opened in October 1861. The location of Chimborazo, near transportation and a good water supply, and its exemplary chief surgeon and administrator, Dr. James McCaw, made it a model hospital for much of the war, though like other facilities it was plagued by supply shortages common in the wartime South. McCaw and his staff, including many women caregivers, made the most of available resources and even raised vegetables and had dairy cows on site. The museum has exhibits on the hospital and Civil War medicine in general. There is also a Confederate cemetery nearby.

From Chimborazo, take U.S. 360 (Mechanicsville Turnpike) north to the Richmond NBP’s Chickahominy Bluff Unit. Before Lee could launch an offensive with his newly named Army of Northern Virginia, he needed Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley army to reinforce the troops defending Richmond. Jackson was just getting out of the Valley after throwing a scare into Washington so great that McClellan had been denied the second prong of his campaign, a large force under Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell that President Abraham Lincoln and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton ordered to remain in the vicinity of Fredericksburg to help protect the Union capital. Lee used the lull to send out a cavalry reconnaissance under a dashing young commander he had known before the war, Brig. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart.

Stuart’s first Civil War assignment under Lee was a huge success. Beginning on June 12, he led 1,200 troopers, including little-known Lieutenant John S. Mosby, north on a ride around McClellan’s 100,000-man Army of the Potomac, returning to Richmond on June 15 with valuable intelligence. Foremost, he discovered that the V Corps under Brig. Gen. Fitz-John Porter had not refused and fortified its right flank north of Totopotmoy Creek.

The return of the Confederate horsemen to the capital provided a morale boost for Southerners even as Lee’s first order to his men—to dig in and strengthen fortifications—was eliciting grumblings and derogatory nicknames for the general (e.g., the “King of Spades”) from some pundits.

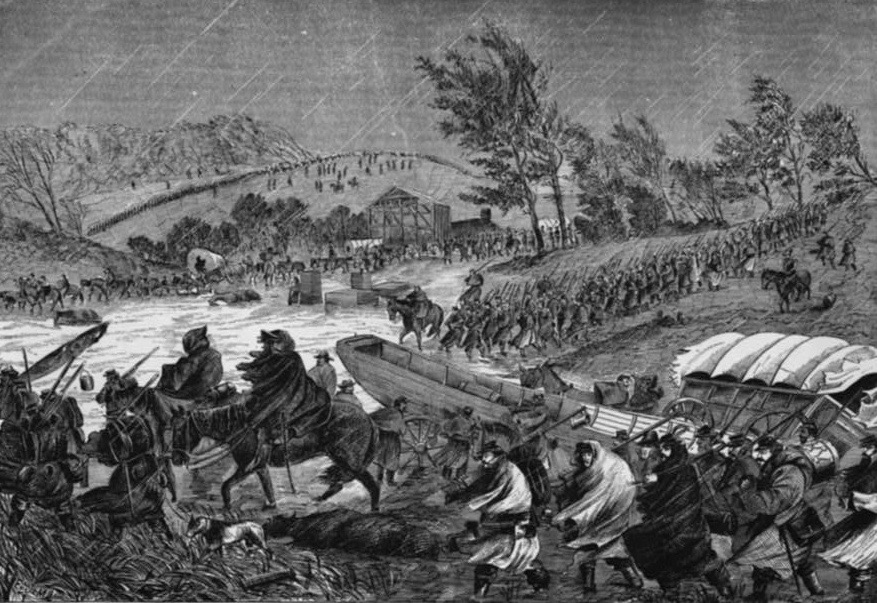

Jackson arrived in Richmond ahead of his army, which was still in the process of marching the 120 miles from the Valley, and assured Lee that his men would arrive on June 26. Lee formed seven corps of unequal strength—much smaller than those that would later form his army—under Jackson and Maj. Gens. Ambrose Powell Hill, Daniel Harvey Hill, James Longstreet, John B. Magruder, Benjamin Huger and Theophilus H. Holmes. Lee’s plan called for D.H. Hill, Longstreet and A.P. Hill to cross the Chickahominy River, which bisects the Peninsula east of Richmond, and attack Porter’s V Corps. Meanwhile, Jackson would cross Totopotmoy Creek and flank the Union force in an effort to cut its supply line at White House Landing. Before that could happen, however, McClellan on June 25 advanced his skirmish lines north and south of the Williamsburg Road to Oak Grove so he could bring his siege guns close enough to strike Richmond. In the ensuing attack, McClellan’s only tactical offensive during the Seven Days’ campaign, the Federals were slowed down by swampy terrain and gained only limited ground before darkness halted the fighting. Lee seized the initiative the following day.

Chickahominy Bluff, along Richmond’s intermediate defense line, served as the vantage point from which Lee observed the opening of his offensive on June 26. Still visible here are traces of earthworks that were constructed after the Seven Days’ battles and manned whenever Richmond was threatened. Continue a short distance northeast on U.S. 360, then turn right on Va. 156 (now called Battlefield Park Route) to the marker for the Beaver Dam Creek Unit. This is the route the Confederates took in their advance on June 26.

Things went wrong for the Rebels from the outset. Jackson failed to appear as pledged by midafternoon. Modern analysis of the campaign has attributed the strange lethargy that seemed to envelop Jackson to stress fatigue—certainly he and his men were still exhausted by their strenuous Shenandoah Valley campaign. Further, the impulsive A.P. Hill started the attack independently against a well-entrenched Federal position. Rebel casualties were high, yet McClellan, believing he was outnumbered 2-to-1, had Porter withdraw his corps to Gaines’ Mill during the night.

The Confederates had been driving Federal pickets from Mechanicsville until the middle of the afternoon, only to be abruptly slowed by the difficult landscape surrounding Beaver Dam Creek near Ellerson’s Mill. The Park Service erected a footbridge across the creek in the past decade to show the perspective the two foes faced at this point, particularly the sloping ground the Rebels needed to traverse. Viewing the stream, millpond and eastern slope, and imagining abatis, earthworks and withering musket and cannon fire, it is easy to understand what Hill’s men were up against. The traces of Ellerson’s Mill can be seen on the eastern side of the creek.

At this point, return to Battlefield Park Route (Va. 156), turn right and proceed east to Va. 718, the turnoff for the Watt House– Gaines’ Mill Unit. Historical markers along the route indicate troop positions and movements prior to the battle, as well as the site of Gaines’ Mill, just north of where the road crosses Powhite Creek. A marker at Walnut Grove Church indicates the site where Lee and Jackson met before this battle.

At Gaines’ Mill on June 27, in what would be their only tactical victory of the Seven Days’ battles, the Confederates attacked the V Corps across Boatswain Creek. Though isolated, Porter’s force had been reinforced to 36,000 men and was in a good defensive position, able to keep the Rebels at bay for five hours of vicious fighting. A breakthrough finally came on the Union left at 7 p.m., spearheaded by Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Brigade with support from Colonel Evander M. Law’s Brigade and other units from Longstreet’s corps. The coordinated assault eventually forced Porter to retreat across the Chickahominy under cover of darkness.

The next day, McClellan ordered what he called a “change of base,” from White House on the Pamunkey River, the inland extension of the York River, to Harrison’s Landing on the James. Many of McClellan’s subordinates, particularly Brig. Gens. Philip Kearny and Joseph Hooker, objected to the movement—which they saw as a retreat.

The Watt House, which Porter used as his headquarters at Gaines’ Mill, is a restored 1835 farmhouse. The interior of the house is not open for public viewing. The mill itself was burned by Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s cavalry in 1864. A trail leads to Breakthrough Point, where Hood’s men began the successful Confederate assault in the evening. A spur trail leads to the position of the Union left during the battle and to a new monument to Brig. Gen. Cadmus M. Wilcox’s Alabama Brigade.

Return to Va. 156 and continue east and south across the Chickahominy near the site of Grapevine Bridge to U.S. 60 (Williamsburg Road). After crossing the tracks of the former Richmond & York River Railroad, the Fair Oaks station is located less than a mile to the left. Take Williamsburg Road a short distance toward Richmond. A historical marker indicates the site of the previously mentioned Battle of Oak Grove. Turn back to the west on Williamsburg Road. Just west of the intersection of U.S. 60 and Va. 33, a Virginia Civil War Trails (CWT) marker offers information on the Seven Pines battle, and nearby is Seven Pines National Cemetery. Continue west on U.S. 60 to where Va. 156 intersects it on the right. Take Meadow Road opposite Va. 156 to the north and around a curve to the left. You will soon come upon a Virginia CWT marker for Savage’s Station, the battle that occurred on June 29th.

On June 28, Magruder opposed the main Federal position south of the Chickahominy, aided by Huger’s force. After conducting a reconnaissance of the Union position on the 28th, Lee was convinced that McClellan’s move to the James River was real. The next day he ordered Magruder to advance eastward along the Williamsburg Stage Road and attack what he anticipated would be the Union supply train guard. Instead Magruder ran into the Federal corps commanded by Maj. Gens. Edwin V. Sumner and William B. Franklin. It quickly became apparent that Magruder did not have an adequate battle plan.

Furthermore, Jackson’s army was busy rebuilding the Grapevine Bridge and failed to get behind the Yankee position as Lee had hoped. The clash on June 29 caused more Confederate casualties and resulted in another tactical defeat, and the Federal march to the James continued. Meanwhile, Colonel Henry Hunt, in charge of McClellan’s Artillery Reserve Corps, had begun to post guns on Malvern Hill.

Lee continued to be aggressive on June 30, using all seven corps for the first time. At White Oak Swamp, Jackson’s and D.H. Hill’s men were held back by the well-placed artillery of Franklin’s reinforced VI Corps. The Federals destroyed White Oak Bridge, one of two major river crossing points in the area, and Jackson, apparently still not sensing the urgency of the campaign, failed to get his men across a nearby ford. The fight at White Oak Swamp, however, was a sideshow to a larger battle taking place farther south: Glendale, also known as the Battle of Frayser’s Farm.

The Battle of Savage’s Station on the 29th had begun at Allen’s Farm near Seven Pines and moved east to this area, where the Federal line ran perpendicular to the road and railroad. From Savage’s Station, return to the intersection with U.S. 60, cross it as the roadway becomes Va. 156 (Elko Road) and continue across the railroad tracks to the Virginia CWT marker for White Oak Swamp. Then continue south to the intersection with Charles City Road, and turn right as Va. 156 runs a short distance west until it turns left onto Willis Church Road—the point where you enter the Richmond NBP’s Glendale Unit.

While Jackson was bogged down at White Oak Swamp, Magruder failed to effectively commit his force to the fight taking place at Glendale. Huger’s men had to clear trees that had been felled on the Charles City Road along which they were advancing, contributing to one of Glendale’s nicknames—the “Battle of the Axes.” The small corps commanded by Maj. Gen. Holmes was checked by Brig. Gen. George Sykes’ division as Holmes attempted to get between the Federals and the river. That left the heavy fighting at Glendale to A.P. Hill and Longstreet, who assaulted four Federal divisions at 4 p.m. The Rebels were temporarily successful against Brig. Gen. George A. McCall’s division until soldiers under Hooker, Kearny and Brig. Gen. John Sedgwick launched counterattacks that stabilized the Union line and protected the last of the withdrawing wagons. As the fighting raged into the night on June 30, McClellan withdrew his forces to Malvern Hill, where they were protected by the reserve artillery and the Union gunboats on the James River.

Glendale Visitor Center at the Glendale National Cemetery is a seasonally manned facility. At Darbytown Road and Va. 156, historical markers describe the Battle of Glendale. The left portion of the Union line extended south to the Willis Church, which burned down in the 1890s but has been rebuilt. The Battle of the Axes occurred along the portion of Charles City Road northwest of its intersection with Va. 156 at the Glendale Unit entrance. Holmes’ advance was stalled along Va. 5 (New Market Road), west of Malvern Hill. Continue south a short distance on Va. 156 to Malvern Hill.

The Federal defensive position on Malvern Hill was strong. Set up on a plateau in a 11⁄2-mile arc were three corps of infantry and a line of 100 guns. They were backed by the Federal gunboats and 150 cannons that had been placed in reserve. Even a coordinated assault by Lee’s entire force would have struggled against this daunting alignment. But Lee apparently did not provide definitive orders this time, and once again corps commanders did not have their forces prepared for an early strike. A plan by Longstreet to amass 140 guns so they could enfilade the Union position went awry when only 20 guns were manhandled into position. Those cannons were quickly silenced.

Lee directed his commanders to follow the lead of Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, who began to advance once the enfilading cannon fire did its work on the Federal defenses. When the artillery barrage failed, Lee searched for another plan of attack but did not inform his corps commanders. Armistead managed to advance and counter the deadly fire of Northern skirmishers, and Magruder, anxious to make amends after letting Lee down once already, brought two of Huger’s brigades forward. Other disjointed and bloody assaults across the wheat fields at the base of Malvern Hill resulted in 5,355 casualties for the South—more than a quarter of the total casualties suffered by Confederates during the campaign. Federal casualties were about 3,000 men (many of them missing and presumed captured), just less than 20 percent of what they would lose in the campaign. Despite the victory, the Federals continued their withdrawal toward Harrison’s Landing.

Malvern Hill has interpretative markers, artillery pieces and walking trails. The Richmond NBP includes the area of a Federal salient held by the men under Brig. Gen. George W. Morell and adjacent land where the Confederates came close to breaking through before falling back. Other areas of Malvern Hill are being acquired by conservation groups to help preserve the battlefield. Two historic plantations southeast of Malvern Hill are open for touring. Berkeley Plantation, on Va. 5, served as McClellan’s headquarters. Shirley Plantation on Va. 608 was the birthplace of Robert E. Lee’s mother.

From Malvern Hill, take Va. 156 a short distance to the intersection with Va. 5 and return to Richmond via Va. 5 North. Or you can continue to the final stop on this tour, Drewry’s Bluff, by entering I-295 south to Exit 15, taking Hundred Road a short distance west and turning right on U.S. 1/301 (Jefferson Davis Highway), then proceeding north to Va. 656 (Bellwood Road). A shorter route is to cross the river on the new Pocahontas Parkway, I-895, and follow U.S. 1/301 south to Va. 656, but be prepared to pay a toll. Head east and turn left on Fort Darling Road, the entrance to the Richmond NBP’s Drewry’s Bluff Unit.

The Confederate artillery position at Drewry’s Bluff on the James River exchanged fire with U.S. Navy gunboats, including the ironclad USS Monitor, preventing them from reaching a position where they could shell Richmond. The earthen Fort Darling and its 8-inch Columbiad guns still stand guard over the James. Interpretive signs describe the duel with Union gunboats and the training of Confederate sailors and marines here. From Drewry’s Bluff, return to Richmond via U.S. 1/301 or I-95.

In preparing for the Seven Days’ battles, Lee devised a plan that was ultimately successful in driving the Northern invaders from the gates of Richmond. Yet he was not particularly well served by his corps commanders, especially Jackson, and the Confederates suffered casualties that proved extremely costly given their limited troop resources.

By contrast, the subordinate officers in the Army of the Potomac showed great skill and valor in carrying out their assignments, but it was the army’s leader who ultimately failed the North. By consistently overestimating Confederate troop strengths, despite—or perhaps because of—having access to several forms of intelligence, McClellan retreated to “save his army” just when he had the South in a precarious position.

Originally published in the June 2007 issue of Civil War Times. To subscribe, click here.