Details of the secret CIA-sponsored war in Laos during the Vietnam War came to light beginning in the late 1980s with the publication of more than a few books on the subject. The most revealing included Jane Hamilton-Merritt’s Tragic Mountains (1993), Christopher Robbins’ The Ravens (1987), Roger Warner’s Back Fire (1995) and Kenneth Conboy’s Shadow War (1995).

One aspect of the United States’ so-called “secret war” in Laos, however, remains relatively little known in this country: the U.S. Air Force/CIA program that recruited young airmen from Laos’ Hmong mountain tribes to fly dangerous missions for the Royal Lao government in its civil war against Pathet Lao communist forces.

Chia Vang, who was born in Laos and came to the United States as a child in the early 1970s, has been trying to give those airmen the recognition they are due. A history professor at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee specializing in the Hmong diaspora, Vang interviewed several dozen Hmong pilots, their family members and their one-time American advisers for her 2019 book, Fly Until You Die: An Oral History of Hmong Pilots in the Vietnam War.

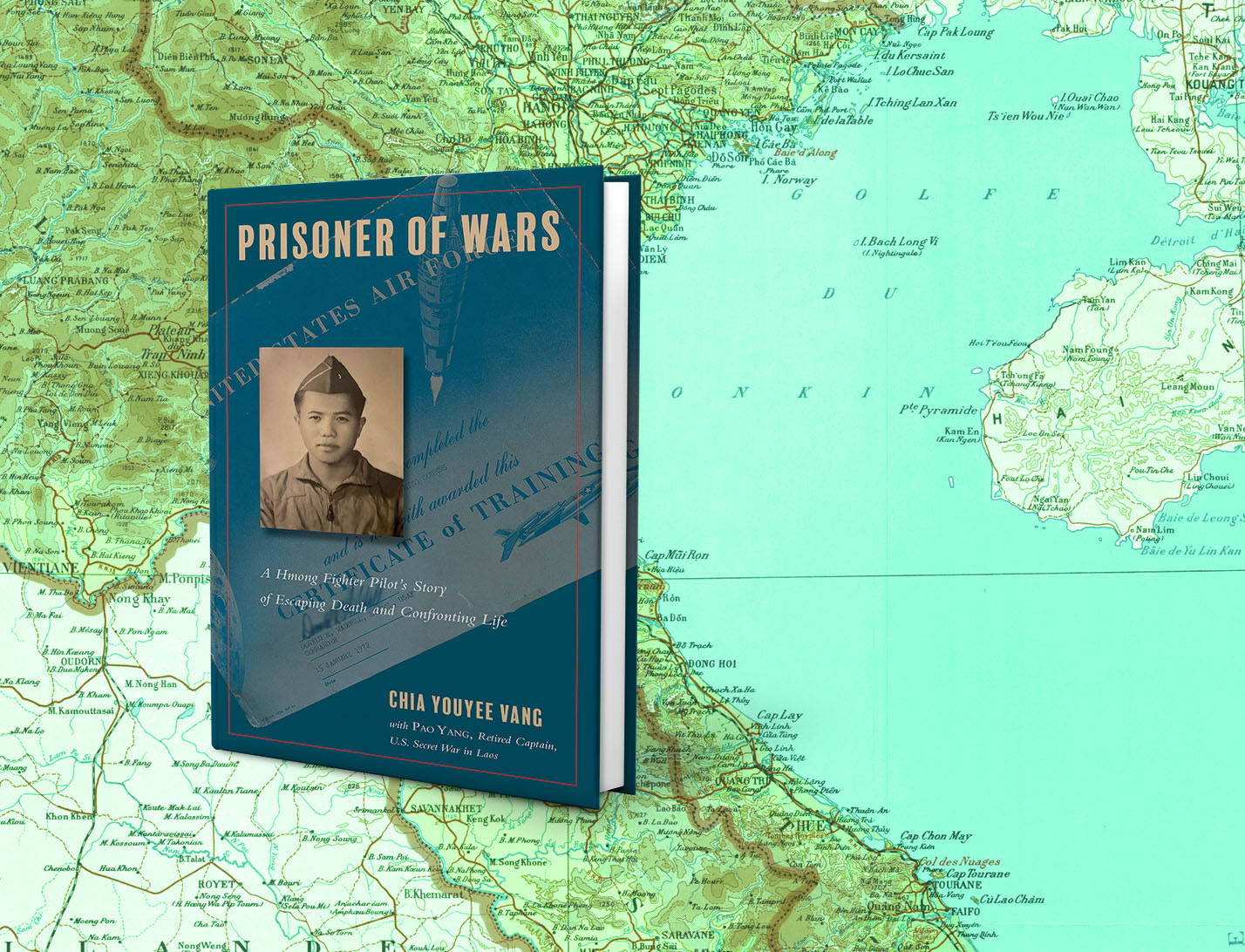

Her new book, Prisoner of Wars, is a concise biography of former Hmong pilot Pao Yang, who—as the title indicates—was shot down during a bombing mission and taken to a remote Lao prisoner of war camp in 1972. Vang interviewed Yang for her oral history.

In the new book, she tells his story, focusing on Yang’s time as a POW, his escape with family members to Thailand and their up-and-down saga after settling in the United States. Yang and his family joined some 50,000 other Hmong refugees in the U.S.—a segment of “the collateral damage that has been left out of dominant Vietnam War narratives,” Vang notes.

Yang, who was able to overcome the rural poverty of his youth and become a military pilot, is an “impactful illustration of the possibilities that existed at the time for a humble Hmong… to gain access to the U.S.-sponsored military bureaucracy,” Vang writes.

His life, she says, “provides a unique lens through which to better understand the lasting impact of the wars in Southeast Asia” over the past two centuries.

Like other Hmong pilots, Yang flew a piston-engine T-28D Trojan trainer remodeled into a rudimentary dive bomber—“poor-quality aircraft that were no longer used in Vietnam,” Vang notes, adding that the planes were moved to Laos “without regard for the safety of local pilots and the American volunteers who flew with them.”

The Pathet Lao released Yang from the POW camp in late October 1976 but did not permit him to leave the country. He was forced to perform arduous manual labor building bridges and working on farms and in sawmills. That ordeal lasted nearly three years before Yang gathered members of his family, including his second wife and child, and undertook a hazardous journey by foot to the Thai border. The family made it out of Laos, spent time in a refugee camp in Thailand and arrived in the U.S. in late December 1979.

Yang and his family came to America with little money. They could find only menial jobs and moved frequently. The family survived, but the acclimation was extremely difficult for everyone, including Yang’s American-born children.

Prisoner of Wars is a valuable book that adds to the ongoing saga of the continuing, multifaceted legacy of the American war in Vietnam.

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: