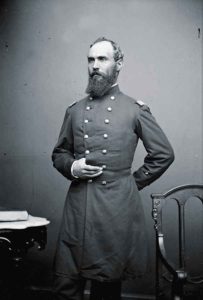

The Daniel E. Sickles scorecard has two particularly unforgettable entries. The first is February 27, 1859, the day Sickles, a New York Democratic politician, murdered his young wife’s lover, Philip Barton Key II, in broad daylight near the White House. The second is July 2, 1863, when Sickles—now a Union major general—lost a leg to a cannonball at Gettysburg while nearly costing the Army of the Potomac victory with an ill-advised decision to reposition his 3rd Corps on Cemetery Ridge. By pleading temporary insanity—the first defendant to do so successfully in this country—Sickles got away with the murder of Key, son of the famed Francis Scott Key. As for the grievous wound at Gettysburg, it fortunately ended Sickles’ military career, which had been trouble-plagued from the beginning of the war. That he was in uniform in the first place shows just how desperate President Abraham Lincoln was to forge the type of political alliance he knew was necessary to save the Union—even if it meant embracing a rascal like Dan Sickles.

The prewar notoriety associated with Sickles’ name was further exacerbated by a dreadful incident on October 21, 1861. Soldiers in the Excelsior Brigade, a unit Sickles had created and now commanded, were joking and laughing around their campfire on a mild evening in southern Maryland. They had been in the region only a few days, and excitement for their new assignment ran high. It wasn’t long before a soldier produced a Confederate cannon ball, one of many that had been fired from the Virginia side of the Potomac River, intended to sink Union shipping heading for Washington, D.C. Someone had brought the ball into camp earlier in the day, and while it was being examined, a substantial amount of powder had been poured out and placed aside. For the bored young men from western New York, the projectile inevitably became a plaything.

Before long, the idea of shoving some sort of ember into the ball’s fuse hole took hold—a challenge quickly taken up by one of the soldiers, Private John Rouse of Company E, 3rd Excelsior. Within an instant the ball exploded, sending fragments of iron as well as men flying in every direction. Rouse died almost instantly, Sergeant Michael Daly a few days later. Many others were left to suffer from various wounds.

For Sickles, the exploding ball incident wouldn’t be the last in a run of serious setbacks. A few days earlier, on October 11, Sickles’ Excelsior Brigade, which he had raised with New York state volunteers, was combined with another brigade to form a new division under Brig. Gen. Joseph Hooker. The 10,000 men or so in Hooker’s new division were tasked with suppressing Rebel activity in southern Maryland and in keeping the Potomac open for Union shipping.

The path from New York early in the war would not be easy for Sickles. He first had to fight hard to keep his command together and overcome a hostile governor, then disgruntled subordinates, a contemptuous commander, and discontented regiments—not to mention getting fired twice.

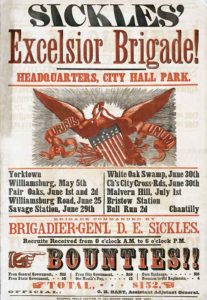

Sickles received approval to form a regiment in the spring of 1861, but soon had permission to create an entire brigade, which he christened Excelsior (Latin for “Ever Upward”—the New York state motto). Sickles promised the brigade would represent the entire state, proposing five regiments to be designated 1st Excelsior, 2nd Excelsior, etc. Recruiting was good at first, as men flocked to join the charismatic Sickles. When the process slowed, he followed the lead of other commanders and struck bargains with men facing prison time, offering them a choice of enlistment or incarceration.

Organizing the brigade proved a messy affair. When men complained that their enlistment agreements had been breached and they wished to go home, Sickles either ignored their claims or threatened arrest. Amid accusations of corruption and double-dealing, Sickles was eventually able to cobble together his five regiments, collected from 12 New York counties and five other states. Some companies were formed from local militia units, with competent company officers and hometown backing. Others, however, had been scraped together from the lowest rungs of New York City society, prompting the Rev. Joseph O’Hagan, the Excelsior Brigade’s chaplain, to assert: “Such a collection of men was never before united in one body since the flood.”

Sickles’ first adversary, even before the brigade left New York, was Republican Governor Edwin Morgan. Citing dissatisfaction from upstate counties over Sickles’ recruiting methods, Morgan ordered disbanding of all but 10 of the Excelsior Brigade’s 50 companies. Undeterred and smelling the foul air of party politics, the Democrat Sickles appealed directly to President Lincoln and eventually kept his brigade intact, though it now had a “United States Volunteers” designation.

The next problem involved one of his regimental colonels, James Fairman. There had been many delays in completing the ranks of Fairman’s 4th Excelsior, which was filled mostly with New York City firemen. Many officers questioned Fairman’s abilities and resented his overbearing style, although the rank and file seemed to like him. With some members of the brigade in Washington, D.C., and 4th Excelsior still waiting at Staten Island, Fairman’s simmering feud with Sickles finally boiled over. Fairman had become convinced that Sickles intended to deprive the regiment of its prized “Second Fire Zouave” designation. Furthermore, Fairman was certain Sickles was unfit for command, saying openly he and his regiment were trapped under a “second-rate general.”

Hearing that, Sickles moved to get rid of Fairman by ordering that the troublesome colonel be barred from boarding the ship that was to carry the regiment from New York. The men of 4th Excelsior were initially outraged, but came to appreciate Sickles’ bold action. Fairman was later court-martialed for conduct prejudicial to good order while leading the 96th New York during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign. The Excelsior Brigade became part of the force protecting Washington during the widespread anguish in the North that followed the Union defeat at First Bull Run on July 21. Men from the different regiments built forts and other defenses on the capital’s southeast side. Battalions drawn from across the brigade would occasionally set off for several days of adventure in adjacent Charles County, Md., with orders to root out secessionist sympathizers, arrest anti-government provocateurs, and clamp down on rebellious activity. With a seceded Virginia on Washington’s southern doorstep, the last thing Lincoln needed was another Rebel nest to his east.

Despite the expeditions, secessionist men and materiel were making it down from Baltimore, through Charles County, Md., and across the Potomac to Virginia. A large permanent presence in southern Maryland was needed to block this flow and support the Navy’s Potomac Flotilla as it worked to suppress Rebel artillery batteries on the Virginia shore. The Excelsior Brigade, half of Hooker’s newly formed division, would be part of this force.

Starting October 18, Hooker moved his division into southern Maryland. Serving as a large-scale infantry exercise, soldiers were expected to carry gear as they would during combat. Personal belongings were to be kept to a minimum, and no regimental wagons or ambulances were to be used. Hooker’s 1st Brigade, mostly New Englanders, performed flawlessly, but for Sickles things went wrong almost at once.

The general had either ignored Hooker’s directive regarding the wagons or had not passed it along to his commanders. His New Yorkers scrounged wagons and ambulances and filled them with all manner of impedimenta. These wagons, Hooker reported, were used for “lazy soldiers, officers’ and women’s trunks and knapsacks to such an extent as to lead one to fear that if they reached camp at all, it would be with crippled horses and broken down ambulances…”

Already scornful of the political general, Hooker was outraged. Worse still, commanders of 2nd Excelsior had failed to provide food for their men. As the march extended and hunger set in, “the result,” as one regimental officer reported, “could be expected.” Men fell out to chase game, forage, and cook whatever was caught. The line unraveled and eventually Sickles’ unit was stretched out for miles, a hopeless rabble.

Hooker reported Sickles’ poor performance to the commanding general, George B. McClellan. Sickles protested vociferously, and was able to keep his command while 2nd Excelsior commander Colonel George B. Hall was arrested for negligence, with Lt. Col. Henry Potter taking over. Hall eventually returned to command, but not before the regiment had splintered into factions over who was best suited for command, with officers leveling charges at one another. The hard feelings came to an ugly head one winter evening, when after a regimental parade in front of Hooker, the officers took to drinking. Soon the regiment was embroiled in a fight between “Hall Sympathizers” and “Potter Men.” The brawl was almost serious enough to warrant disbanding of the regiment. Hooker and Sickles eventually allowed Hall and Potter to remain at their posts, which only made service in the regiment tense and miserable.

Sickles’ brigade settled into a soldierly routine of patrolling the lower part of the state, from the southern reaches of Baltimore all the way to Point Lookout in St. Mary’s County. The men chased down suspected Confederate sympathizers and administered loyalty oaths, although the sincerity of these oaths was no doubt questionable. “The people here are all secessionist, and it is only the presence of an overpowering Union force which cause them to feign loyalty,” confided one local Unionist. “They are all ready to take the oath of allegiance; that doesn’t hurt them a bit; but just so soon as they think they can help Jeff Davis, so soon their dispatches will be sent.”

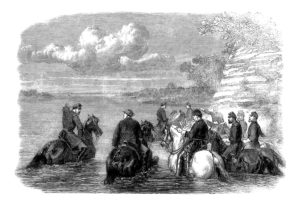

After a few weeks of accepting put-on loyalty oaths and watching the Rebel batteries duel with the Federal flotilla, many men and most officers began to wonder, where was the glorious war they had signed up for? Hooker even appealed to McClellan to allow him to conduct operations across the river into Virginia. McClellan demurred, leaving Hooker and his division frustrated. Undeterred, one enterprising colonel under Sickles in early November gathered up 400 hand-picked men, commandeered some tugs from the flotilla, and conducted a midnight raid into Virginia.

The material results of the raid were meager, but the effect on morale was spectacular—finally the men were doing something war-like. Sickles was pleased by the initiative his commander had shown. Hooker was less thrilled, but since the foray had come off without incident, he forgave the breach in discipline. McClellan on the other hand was livid over collapse of command and control, making his feelings known to both Hooker and Sickles. His reprimand served only to reinforce the popular notion that when it came to fighting Confederates, “Little Mac” was all bluster and no action.

That fall, the federal government called upon loyal states to meet their manpower quotas. This added pressure forced Governor Morgan to reconsider incorporating Sickles and his Excelsior Brigade into the state’s manpower quota. With its new status as a New York unit, the brigade now had fresh numerical designations for the five regiments: the 70th through 74th New York State Volunteers.

Sickles had originally been given the rank of colonel. To lead a brigade, he needed confirmation by the Senate as a brigadier general. Given Sickles’ political past, many senators were ambivalent about his confirmation while others were downright opposed. Republican firebrands questioned the wisdom of giving such high command to this “otherwise minded” man, fearing the Democrat could march the entire brigade over to the enemy.

But Sickles would not sit idly by while the fickle winds of politics played upon his nomination. While his brigade chased secessionists around Maryland, Sickles was frequently absent, back in Washington counting votes and handing out necessary blandishments to secure his nomination. In his absence, Nelson Taylor, colonel of 3rd Excelsior (72nd New York), commanded the brigade. Taylor was a veteran of the Mexican War, had served in the California legislature, and was a Harvard-educated lawyer. Hooker liked Taylor, and many throughout the brigade, especially in the 72nd New York, thought Taylor’s handling of the brigade far superior to Sickles’.

Dissatisfaction was growing within the brigade and especially in 3rd Excelsior, where a number of former militia officers served. Many felt they had been relegated to a backwater region to “police a Maryland highway” while the real action happened elsewhere. Wrote Private Arthur McKinstry of Fredonia, N.Y.:

[T]he Excelsior Brigade has never been so well managed as when…Col. Taylor has been acting brigadier. Sickles displayed great energy and patriotism in the raising and equipment of the brigade. He has governed it however in a civilian manner, and whatever talent and administrative ability he may have, he is evidently incompetent to personally maneuver the brigade….I think that we might have played some other role than that of special policemen, and labored up on a Maryland highway, if we had been headed by an experienced soldier.

Others believed that being commanded by a general like Dan Sickles would ensure they remained disappointedly far from the fighting. Transfer to another brigade, especially one commanded by a competent officer who would be allowed to take his men into battle, seemed the only clear path for the men of the 72nd. In this climate, a petition was signed “by nearly every officer” asking the regiment be transferred to another brigade. Sickles’ bravery, energy in forming the brigade, or his deserving of command was beyond question—they just wanted to fight.

The Senate began debating Sickles’ confirmation in the spring of 1862. Whether 3rd Excelsior’s petition was even considered or if Sickles’ own poor reputation was enough, the Senate on March 17 rejected his brigadier general nomination. Radical Republicans and Morgan had had the last laugh. Hooker immediately issued orders to relieve the troublesome Sickles and place Taylor in temporary command of the Excelsior Brigade. Sickles argued that an appeal was in order since he technically was senior colonel within the brigade. Hooker reluctantly conceded to Sickles’ argument, leaving the bigger issue of brigade command still undecided.

Despite the vote, Sickles was soon back in Maryland leading the brigade. Private McKinstry wrote in a letter home:

We have had more brigade drills lately, and Gen. Sickles has done much better than his former management would have justified our expecting. I cannot but admire his indomitable resolution and have no mean opinion of his talent. If the time spent at Washington in intriguing for the confirmation of the Generalship had been employed as at present, I believe his nomination would have been more favorably received….If Sickles is to be our General why not confirm him and let him apply himself to his business? If he is not to be, why not at once appoint his successor and let him assume his harness as promptly as possible. It should be…a source of humiliation that military experience and signal ability have weighted so lightly when opposed to political trickery and partisan prejudices.

Neither Sickles nor his political guardian angel, Lincoln, took the Senate’s vote lying down. As Republican newspapers howled in protest, Lincoln renominated Sickles. An editorial in the western New York Fredonia Censor charged Lincoln with taking the soldiers’ welfare lightly:

The President has re-nominated Gen. Sickles as a Brigadier General. By what maneuvering he was induced to do this in the face of the unanimous rejection of Sickles’ nomination by the Senate, is a mystery the people would like to have unraveled. Sickles’ friends pretend that this rejection was brought by the misapprehension of facts, which has been explained away. But no explanation can do away with the damaging fact that Sickles has not the confidence of his men, and that his best officers signed a petition to be transferred from his command. In time of war no one ought to be appointed to a military position unless fully competent for the discharge of its duties…

The pace of events in Maryland picked up in March and early April. With the strategic situation changing, Sickles’ men had become more active, launching larger raids against suspected Rebel installations in the Old Dominion. By April 1, orders had come to remove the sick and prepare to move out. When Sickles returned from a successful raid a few days later, two letters containing orders awaited him. The first, which all had expected: Leave Camp Wool and begin packing onto transport steamers waiting to take them to the seat of war and the upcoming campaign season. The second, a crushing surprise—Dan Sickles no longer commanded the Excelsior Brigade.

Like many of the men, divisional commander Hooker had long agreed Sickles was unfit for command. And with all of Sickles’ appeals exhausted and the division’s move to the Peninsula imminent, Hooker issued orders to sack Sickles. He was to stay behind while Taylor took the Excelsior Brigade to Virginia. On board the steamer Elm City, in a cabin Sickles had used as his office, the now-deposed commander penned his farewell address to the brigade he had created. “My last act of duty is to bid you farewell,” Sickles’ General Orders No. 6 read. And after restating what he saw as unjust circumstances surrounding his dismissal, Sickles impressed upon the men that, “Whether we are separated for a day or forever, the fervent wishes of my heart will follow your fortunes on every field.”

Despite the heartfelt nature of the address, during the commotion of loading, it is likely few actually heard the farewell. The Excelsior Brigade arrived on the Peninsula on April 11, in time to join McClellan’s push toward Richmond. Within a month, these New Yorkers under Taylor would fight their bloodiest battle of the war at Williamsburg, Va., losing fully one-fourth of their number. But the paths of Sickles and the Excelsior Brigade would come together again and would remain intertwined until Dan’s most controversial day of his generalship—Day 2 at Gettysburg.

Rick Barram, a history teacher in northern California, is author of The 72nd New York Infantry in the Civil War: A History and Roster (McFarland, 2014).