Alexander Hamilton’s grandson was born to be a great general, but illness intervened

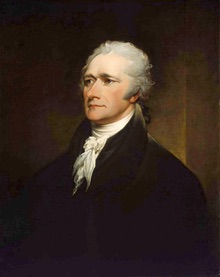

Schuyler Hamilton could not have been born into a family draped with a grander political and military legacy. Both of his grandfathers—Generals Alexander Hamilton and Philip Schuyler—are closely associated with the battle for American independence and the building of the new nation.

Being born into the “Hamilton clan,” Schuyler undoubtedly regarded it as his generation’s duty to emulate the heroes of the Revolutionary War, most importantly through heroism on the battlefield. Schuyler Hamilton did just that with his gallant service during the Mexican War. But this “brilliant officer, who gave great promise,” had an unremarkable career in the Civil War, beset by disease and resigning from the Union Army in 1863.

Born on July 22, 1822, Schuyler was one of the seven children of soldier/lawyer John Church Hamilton. John, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton’s fifth child, served as General William Henry Harrison’s aide-de-camp during the War of 1812. A military career seemed most appropriate for John Hamilton’s second son, and Schuyler entered the U.S. Military Academy in 1837 at the age of 15. He would graduate 24th in West Point’s Class of 1841, two spots ahead of future Gettysburg hero John F. Reynolds. (Other notables to graduate alongside Schuyler were Nathaniel Lyon, Israel “Fighting Dick” Richardson, and cousins Richard and Robert Garnett.)

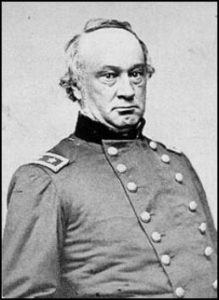

The Rev. George Deshon, a classmate and roommate of Ulysses S. Grant (Class of 1843), remembered that Cadet Hamilton “was always pleasant and cheerful—a good companion and a great favorite.” Hamilton shared a room for two years with future General-in-Chief Henry Halleck, a reclusive New Yorker. Halleck went on to graduate third in his class, and would remain lifelong friends with Schuyler, eventually marrying one of his sisters, Elizabeth, in 1855.

Commissioned a second lieutenant in the 1st U.S. Infantry upon graduation, Schuyler Hamilton served in Iowa and Wisconsin from 1841 to 1844. He returned to West Point in November 1844 and served as the assistant instructor of infantry tactics until June 1845. When Schuyler left the position in 1845, “his friends at the U.S. Military Academy” presented him with a decorated Springfield M-1822 musket.

When war broke out with Mexico in May 1846, expectations were certainly high for Lieutenant Hamilton. An observer noted that the young officer’s “elegance and modesty in the drawing room” complimented his “his gallantry in the field of battle.” He carried some of the same physical features as his famed grandfather, Alexander: deep-set eyes, long nose, strong chin, and a firm jaw and mouth.

Philip Hone, mayor of New York 1826-27 and a noted diarist of the day, was convinced Schuyler Hamilton would live up to his grandfather’s heroic reputation, stating, “With such blood in his veins, and such a name, he could not fail to acquit himself with honor.” Hamilton did not disappoint, returning home a national sensation after risking life and limb helping to secure the body of Lt. Col. William H. Watson, commander of the Battalion of Baltimore and District of Columbia Volunteers, after Watson fell during the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846. He was brevetted a first lieutenant “for gallant and meritorious conduct in several conflicts at Monterrey.”

In the days after the battle, Hamilton’s leg was fractured when he was kicked by Brig. Gen. Thomas Marshall’s horse. After recovering, Hamilton returned to Mexico for Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott’s 1847 amphibious landing at Vera Cruz. Hamilton was Scott’s aide-de-camp, initiating nearly a decade of service under “Old Fuss and Feathers.”

During a meeting of officers at Brevet Brig. Gen. William Worth’s headquarters at Chalco, east of Mexico City, Scott exhibited interest in exploring a foundry in the mountains nearby that was rumored to be manufacturing ammunition for the Mexican army. Hamilton volunteered to lead 15 dragoons to “ascertain its capacity for casting bullets in case they should be required.” Scott favored the idea, but ordered Worth to supply Hamilton with a larger detachment including 50 cavalrymen from the Third Dragoons and 100 men from the Sixth Infantry Regiment.

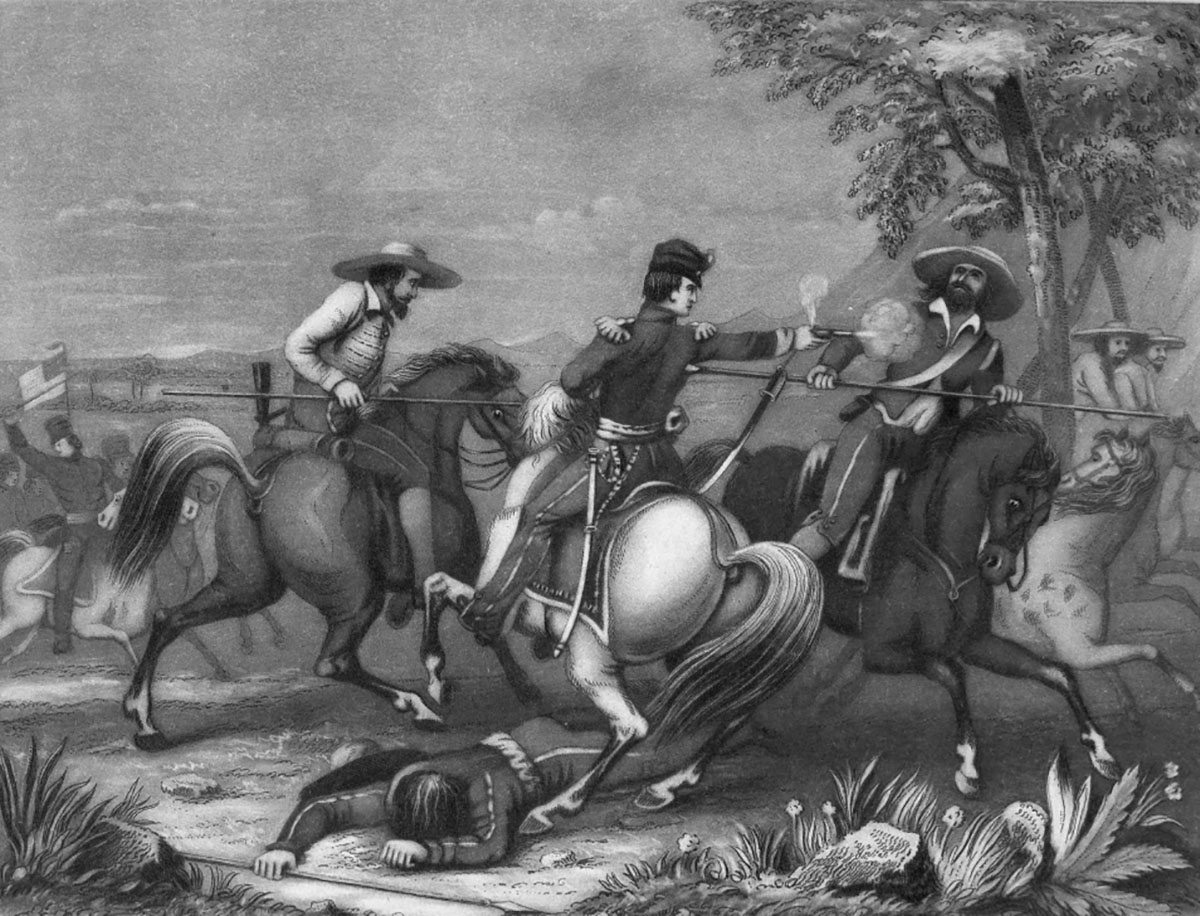

The party reconnoitered the foundry unmolested. On August 13, 1847, Hamilton and the dragoons were riding back to headquarters ahead of the infantry column when a force of 250 Mexican lancers carrying a skull-and-crossbones flag emblazoned with the words “I give no quarter” attacked the outnumbered dragoons. While Hamilton was fighting face-to-face with a Mexican lancer, a second Mexican cavalryman rode past and skewered the American through the back.

The lance point entered Hamilton’s body under the shoulder blade, punctured his right lung and exited near his collarbone. The sheer force of the rider’s thrust and the motion of the horse going in the opposite direction caused the lance head to snap off in Hamilton’s body. Miraculously, the young lieutenant remained upright in his saddle despite this fearful wound. When Captain William Hoffman of the Sixth Infantry arrived on the scene, he ordered his men to assist the wounded officer who “could with difficulty sustain himself on his horse.” Hamilton told Hoffman, “Don’t mind me, sir, but go to the assistance of my party.”

Hoffman’s infantrymen transported the desperately wounded lieutenant on a litter to a hacienda, where a French doctor temporarily cared for him. American surgeons arriving on the scene discovered that the two-and-a-half-inch wide spear point had been embedded six and a half inches into Hamilton’s body. It had to be pried out by breaking two of Hamilton’s ribs. After the surgery was completed, a horse-litter made of tent-cloth and two long canal-boat setting poles allowed the wounded officer to travel “comfortably” on Scott’s march toward Mexico City. Hamilton returned to duty eventually, but this desperate wound caused him misery “which he never ceased to suffer for more than half a century.”

Hamilton’s exploits made him an overnight sensation. Scott reported afterward that the affair was of “great daring and brilliancy” and it won the lieutenant “the esteem and admiration of the whole army.” Hoffman declared that his “conduct is spoken of in the highest terms.” Hamilton even had a poem dedicated to him and a romantic engraving was printed depicting him receiving the lance wound.

Hamilton was brevetted to the rank of captain in August 1847 for “gallant and meritorious conduct” and in November 1848 was presented a Tiffany & Co. sword “as a slight Testimony of the admiration and respect of his fellow citizens and friends of New York for his distinguished gallantry and conduct throughout the Mexican War.”

After the war, Captain Hamilton stayed on Scott’s staff. In 1852, he authored a history of the American flag, which he dedicated to Scott. He also served as secretary to the Board of Commissioners of the Military Asylum (Scott was the president). Described as a “most worthy selection,” he handled all of the pension claims submitted by disabled soldiers.

Hamilton resigned from the army in May 1855, hoping to turn to a future in business. He applied for a position at the bank of Lucas, Turner and Co. in San Francisco, California. Possessing no previous experience as a banker, Hamilton offered to work for the bank’s manager, William T. Sherman, for three months without pay to learn the trade. Sherman accepted this offer, and within a week Hamilton was “diligently and cheerfully performing a variety of tasks.” Sherman and Hamilton appeared to have worked well together, Sherman telling Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing Jr. in 1861 that Hamilton was “a particular friend of mine.”

Hamilton left the banking business the next year and joined his old friend, Henry Halleck, in the mining business. Halleck at the time served as director general of the New Almaden Quicksilver (Mercury) Mine in California. He appointed Hamilton to serve as his assistant chief.

For reasons that are unclear, Hamilton returned east to Branford, Conn., in 1858 and worked as a farmer until the outbreak of the American Civil War. He was one of the first eager applicants arriving at the doorstep of newly appointed Colonel Marshall Lefferts of the 7th New York National Guard seeking a spot in his organization. Hamilton entered the regiment as a lowly private and marched to Washington in April 1861. When Scott discovered that his old acquaintance was in Washington, he had Hamilton appointed to his staff as a military secretary with the rank of lieutenant colonel, followed by a promotion to full colonel.

Hamilton regularly acted as a liaison between President Abraham Lincoln and Scott, who was by this time elderly and in ill health. He remembered one humorous incident in July 1861. About 4 a.m., Hamilton hurried to the White House with a telegraph reporting Brig. Gen. George McClellan’s victory at Rich Mountain in what is now West Virginia. Upon Hamilton’s thump at his door, Lincoln “exhibiting some little vexation” at having been awakened for the sixth time that night, came outside wearing only a red flannel shirt too short for his body, visibly trying to pull it down to cover his bare legs. He had to leave his dressing gown behind with Mrs. Lincoln, who was tangled up in it and in a deep sleep.

Hamilton handed Lincoln the telegraph reassuring him it would bring him “the greatest pleasure.” It had the desired effect, and Lincoln exclaimed, “Colonel, if you will come to me every night with just such telegrams as that I will come out not only in my red shirt but without any shirt at all. Tell General Scott so.”

The newly appointed Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, managing the Department of Missouri, called on his friend once more. He summoned Hamilton to St. Louis in November to serve as his assistant chief of staff. Commissioned a brigadier general of volunteers that same month, Hamilton remained with Halleck until January. Shortly after, he took command of the Second Division in the Army of the Mississippi under Brig. Gen. John Pope, a fellow veteran of Zachary Taylor’s army.

Hamilton got on well with Pope and the other senior officers of the Army of the Mississippi. One of his colleagues was then-Colonel Joseph Plummer, a West Point classmate and fellow officer of the 1st Infantry during the Mexican War. Brigadier General David S. Stanley recalled the regular and relaxed dialogue that existed between these officers, “General Pope, General Gordon Granger, Schuyler Hamilton, Louis Marshall, Edward Kirby Smith, Joe Plummer, George A. Williams, my classmate, were in this army and we had a very pleasant and social set who sat around the campfires in the evening and talked about things old and new. Pope was very agreeable and a very witty man and often turned the laugh on his staff and others.”

Hamilton’s division saw action in the operations leading up to the capture of New Madrid, Mo., and the Confederate river fortress Island No. 10 in February–April 1862. During these maneuvers, Hamilton advised Pope to cut a canal in the bayous east of New Madrid to bypass the Gibraltar-like defenses of Island No. 10. Pope took this advice, and upon completion of the canal, transport ships conveyed his 25,000 soldiers to the rear of the island leading to its fall and the capture of between 4,000–6,000 Confederates. Pope stated in a letter to Halleck that he was “indebted” to Hamilton for the recommendation, and in his official report on May 2, 1862, specified the idea “was suggested to me by General Schuyler Hamilton.”

Hamilton’s notable recommendation generated controversy that lasted for over three decades. Colonel Josiah W. Bissell, the engineer officer who actually built the canal, claimed it was he who suggested it. Colonel George A. Williams insisted the idea came from a saw-mill worker only known as Morrison. Until the end of his life, Hamilton was adamant that others tried to rob him of this credit and that he was the “sole inventor of the project.”

After the fall of New Madrid and Island No. 10, Hamilton commanded the 3rd Division of the Army of the Mississippi and then the Right Wing of the army during the campaign to besiege the Confederate suppy depot at Corinth, Miss., in the spring of 1862. That May, the hardships of field service and poor weather led to Hamilton contracting typhoid fever. He remained in the field even though he was nearly incapacitated, finally going on sick leave in July, still suffering from a combination of chronic diarrhea and severe cramps. He was appointed major general of volunteers in September 1862, though the promotion was never confirmed by the Senate. Hamilton returned to the field in November 1862 at the request of Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, who sought his services in his Army of the Cumberland, but was ordered back to New York in December for treatment.

Never able to overcome his debilitating illness, Hamilton resigned from the army in February 1863, depriving the Union of a resourceful general. One account soberly noted that he “had great experience and ability, but no physical power left.” Brigadier General Manning F. Force remembered Hamilton as, “an officer whose gentle refinement veiled his absolute resolution and endurance till they were called into practice by danger and privation.” President Lincoln reluctantly accepted his resignation, “with much regret,” attributed to the “ill health and disability he incurred in the service of his country, wherein he was highly distinguished for ability and good conduct.” Hamilton returned to his farm and sat out for the remainder of the war, an uneventful end for a soldier with so much promise.

He sought to be named minister to Denmark in 1869 during Grant’s administration, with the blessings of his old friends, William T. Sherman and John Pope. He boasted to Sherman to have been the leading factor in Grant taking command of the army operating against Forts Henry and Donelson. He claimed that he knew “Grant was the man” before he gained his notoriety, urging Halleck to select him over the other two candidates, Samuel R. Curtis and John Pope: “I served Genl Grant once—He does not know it….Without my suggestion it might have been Pope or Curtis instead of Grant.” Even with this reasoning, Hamilton was passed over and instead Christopher Columbus Andrews, another former Civil War general, received the ministerial post.

In 1871 the former soldier petitioned Secretary of War William W. Belknap to be placed on the retired list of the Regular Army with the rank of lieutenant colonel or colonel for his service on Winfield Scott’s staff back in 1861. This request was denied. Hamilton afterward declared that “Some wiseacres in Washington have declared it was not a commission, though I was in the most intimate confidence of President Lincoln, his Cabinet and General Scott, and gave orders in the name of both the President and General Scott to Generals and other high functionaries.”

He served as the hydrographic engineer in the New York City Department of Docks from 1871 until 1875. He returned to the spotlight in 1890 when his son, Robert Ray Hamilton, was found drowned in the Snake River in Yellowstone Park. At a dinner celebrating the 140th anniversary of the birth of Alexander Hamilton, General Hamilton gave an eyewitness account of an accidental meeting between Aaron Burr and Hamilton’s daughter to the pleasure of the dinner’s guests.

The wealthy general was restricted to his New York home in the last years of his life. Brevet Brig. Gen. James Grant Wilson recalled with pleasure “but to the last the General enjoyed his cigar and book, living over again his army experiences with a friend. He was certainly the most cheerful man for one suffering so much from painful bodily infirmities that I have ever met.” His former classmate George Deshon, now a priest of the Catholic Paulist order, wrote in 1903 that, “I have met him several times since the Civil War and always found him the same unaffected pleasant gentleman as before.” Before his death, he was said to have made the modest remark to Wilson, “Well, before you return, I shall be across the river with Scott and Grant and Sherman.” He died of a combination of syncope, colitis, senescence, and asthenia on March 18, 1903, at the age of 83.

The New York Tribune reported his frugal last wishes. “It is my desire that my funeral be the simplest kind, my casket not to exceed in cost $100, and but three or four carriages to follow it to Greenwood Cemetery. Bury me besides my deceased wife, Cornelia, the daughter of Robert Ray and Cornelia Prime.” He left his Tiffany sword, and the attached sword knot originally owned by Alexander Hamilton, to his only surviving son.

Hamilton came up short in achieving his grandfather’s legacy during the Civil War. One can only speculate what role he could have played later in the war had he not been forced to resign in 1863. Rosecrans could have certainly used him as a senior commander in the Army of the Cumberland, but instead Maj. Gen. Joseph J. Reynolds was sent in his place. His connections with Sherman, Halleck, Scott, and even Lincoln certainly would have helped him to find a place as a division or corps commander upon his recovery. If not a spectacular general, Schuyler Hamilton proved to be a resourceful commander for the short duration he served during the Civil War. He will remain one of those thought-provoking “what ifs” of the war.

_____

A Cleveland native, Frank Jastrzembski is the author of Valentine Baker’s Heroic Stand at Tashkessen 1877: A Tarnished British Soldier’s Glorious Victory (2017) and contributes regularly to the blog Emerging Civil War.

This story from America’s Civil War was posted on Historynet.com on May 4, 2020.