Benedict Arnold had the makings of yet another Revolutionary War hero. Famed for having helped to capture Fort Ticonderoga in 1775 and twice wounded leading both Battles of Saratoga in 1777, he was a living legend by the time he participated in the first American “Oath of Allegiance” at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, the following year. Yet Arnold, prompted by jealousy, greed and the influence of Loyalist friends, plotted to surrender West Point to the British (for a price) and by war’s end would serve as a British brigadier, leading attacks against his former soldiers. At war’s end he moved to Canada and then London.

Arnold’s postwar biographers had little interest in creating a nuanced portrait of a flawed man. Instead, they sought to create a perfect villain, an example to children of how an American ought never to act. Just as biographer Parson Weems fabricated George Washington’s cherry tree story to create a positive role model, so author George Canning Hill exaggerated Arnold’s villainy to render an antihero. “All accounts agree that Benedict was a perverse young fellow from the very beginning,” Hill wrote in his 1865 biography of the turncoat. “His heart was bad at the outset.”

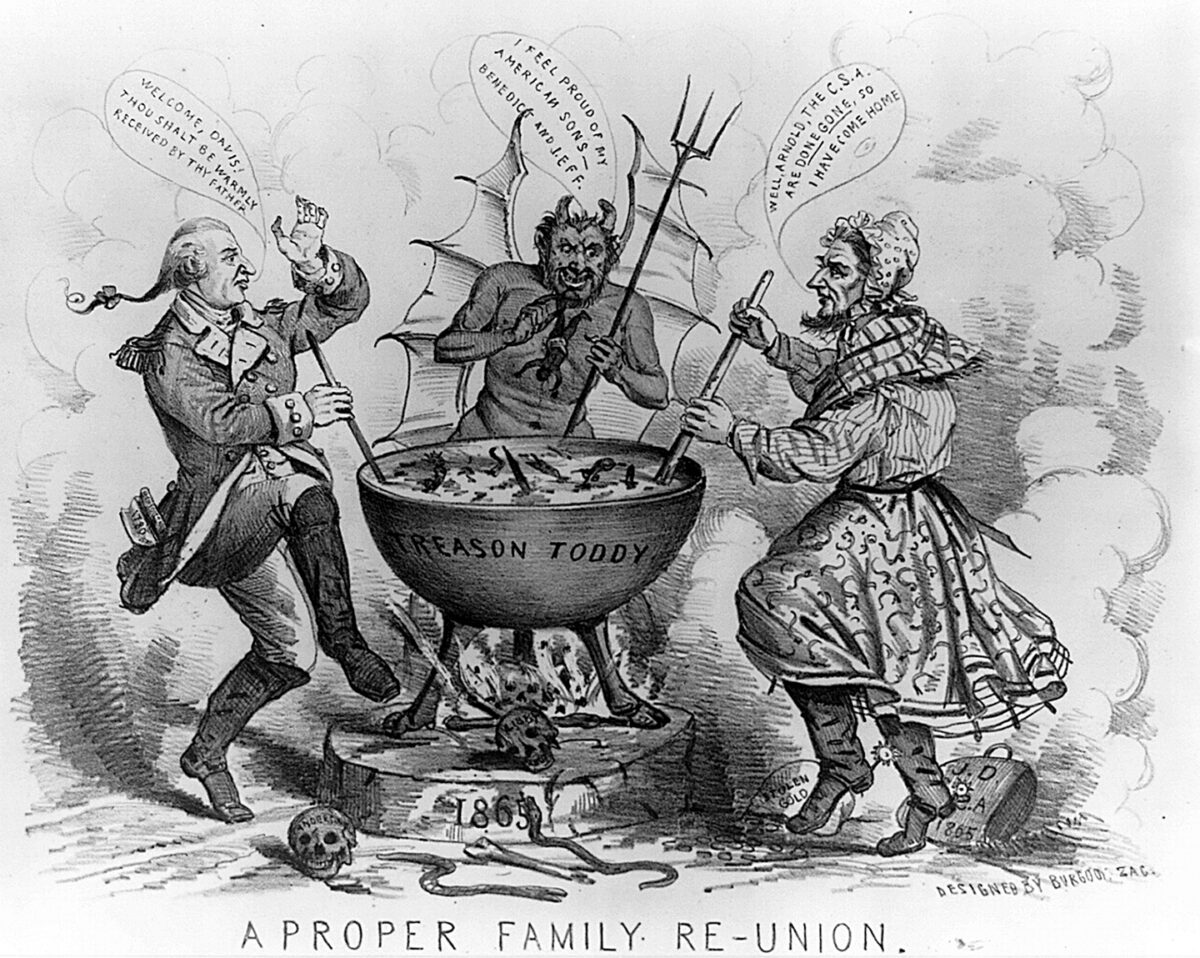

In this 1865 cartoon Arnold is depicted as the Devil’s own son, stirring a “treason toddy” opposite Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, his recently arrived younger brother — who is dressed in women’s clothing based on false rumors surrounding his capture. Intended as more than just an insult to Davis’ character, this caricature was a thinly veiled attempt to add Davis to the roster of American villains, for he too was an American military officer who had betrayed his oath and risen against his own nation. Given that Confederate commanders such as Robert E. Lee and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, were memorialized as misguided heroes (at least for a time), why was Davis so singularly demonized?

In order to heal the divisions caused by the Civil War, federal leaders though it appropriate to highlight the martial courage or honor of Southern fighting men. At the same time, in order to move forward and reinforce an American identity, the nation also needed a villain. Thus, the traits that had been laden on Arnold, namely cowardice and duplicity, were the same ones foisted on Davis.

Both took the fall for a simplified American history, one in which the nation’s triumphs are a direct result of its heroes, and its failings entirely the fault of a few select villains.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.