“The angel of disease and death, ascending from his oozy bed, along the marshy margins of the bottom grounds…floats in his aerial chariot, and in seasons favorable to his progress, spreads mortal desolations as he flies.” Place: Ohio. Date: 1820. Disease: intermittent fevers, the ague, the chills—19th-century terms for the parasitic infection today called malaria. No threat now in the United States, the ailment was then mysterious, widespread, and often fatal.

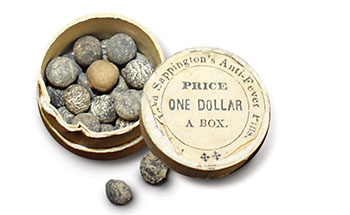

To combat the scourge, John Sappington, a country doctor in Arrow Rock, Missouri, bucked medical convention to concoct and prescribe pills containing quinine. His salesmen peddled the product far and wide, helping to prove the treatment worked by sporadically dosing themselves and never falling ill. If not for Sappington’s popular Anti-Fever Pills, settlers might never have pushed so successfully into the Midwest, validating President Thomas Jefferson’s 1803 gamble on the Louisiana Purchase.

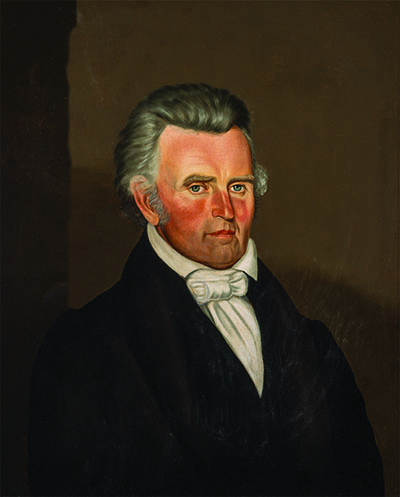

John Sappington, born in 1776, grew up in Tennessee and apprenticed with his physician father, becoming a doctor himself. He headed to Philadelphia for more training but did not complete the course, turned off by bloodletting and other common methods. In 1819, having heard his friend Thomas Hart Benton, an attorney and aspiring politician, talk up opportunities in the Missouri Territory, Sappington, 43, settled in Arrow Rock, a stop on the fur-trade route between St. Louis and Santa Fe. Among his many successful enterprises was a medical practice that would become a platform for challenging healthcare orthodoxy.

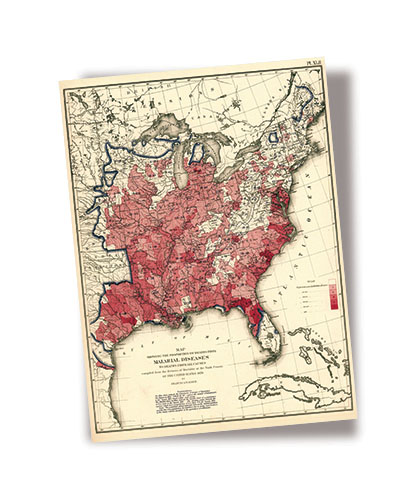

Prolonged chills and fevers often signal the onset of malaria. At the time nobody knew a parasite caused the ague or that mosquito bites transmitted the blood-borne infection. Now we know that malaria is an Old World disease carried to the New World by European colonists and African slaves. In North America, the parasite thrived among mosquitoes in swampy waters like those in the coastal Carolinas, the Mississippi River Valley bottomlands, and the valleys of the Ohio and Missouri Rivers. In the South, malaria was so widespread that its effects may have fostered the image of the lazybones Southerner, but cases also occurred as far north as Michigan, where doggerel warned: “Don’t go to Michigan, the land of ills/the word means ague, fever and chills.”

In Europe, physicians caring for aristocrats had long treated the syndrome with a remedy from the Andes, where Jesuit missionaries had seen Incas use the bark of an evergreen, the cinchona, to treat shivering. In powder form, the bark saw sparing use in America, usually only after a fever had broken.

In 1823, Sappington experimented with the controversial substance. Reading an old pamphlet touting the wonders of “Peruvian bark” prompted him to try it on himself. None of the adverse effects were major, and he started using the bark to treat fever patients at the onset of symptoms. Soon commercial production of a concentrated form of the bark—known as quinine from the Quechua quina—made possible precise dosages. By 1832, Sappington was having his slaves mass-produce in pill form a blend of one grain of quinine, ¼ grain of myrrh, and ¾ grain of licorice, with sassafras added to mask quinine’s bitter flavor; parallel tweaking by British colonials in the tropics led to the gin and tonic. Sappington did not hype his pills’ quinine content because the ingredient was thought to be costly and risky, and medical opinion viewed bloodletting and purging as the best tools against disease.

In the course of two decades, Sappington established a sales network so successful that rivals commonly counterfeited his pills. In 1844, he published The Theory and Treatment of Fevers, which revealed the formula for his famous pills as well as offering patients’ testimonials. Unmasking quinine as the main ingredient, Sappington wrote, would be the most effective way of destigmatizing the drug. His treatise was the first medical book to be published west of the Mississippi. He gave away all copies.

Sappington and his anti-malaria campaign have nearly faded from memory, but a few details flesh out the man. He carried bluegrass seeds that he scattered over bald patches of land. He so dreaded the thought of burial that he ordered a lead-clad coffin, which the physician kept under his bed and filled with apples—except when Sappington occasionally climbed in to check the fit. By the time he died in 1856, at 80, quinine was accepted as a powerful anti-malarial weapon. His coffin still stands aboveground in Arrow Rock at the family cemetery, having withstood damage done by Confederate soldiers scavenging lead for bullets.

Civil war was pivotal to malaria’s spread in North America. Troop movements involving parasite-riddled regions of the Chesapeake Bay and the Mississippi Valley dispersed the organism. During 1861-65, about a million cases of malaria were tallied, and quinine became a fixture in the American military’s drug armamentarium. The disease again threatened American soldiers in World War II due to shortages of quinine, hastening development of substitutes. A DDT spray campaign curbed exposure to mosquitoes among soldiers training in the southern United States and its tropical possessions. By 1946, deaths from the disease had dropped from 60 per 1,000 in 1920 to 2 per 1,000. In 1965, only two deaths were reported in the entire country. Malaria in the United States was no more. Virtually all domestic cases today involve infections acquired abroad. ✯

This story was originally published in the November/December 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.