In 1841 English author Charles Dickens, at work on a book about the United States of America, came for a research tour. He spent a month in New York City acquainting himself with theaters, restaurants, prisons, asylums, neighborhoods, and streets. Having documented London’s Augean slums, Dickens nonetheless goggled at the sight of lower Manhattan’s Five Points. Originally the Collect, a deep freshwater pond that was fouled by chemicals and offal from abattoirs and tanneries, then inexpertly reclaimed with landfill, the Five Points existed in a fog of stench. Named for the five-way intersection at its miasmic heart, the neighborhood barely was keeping itself atop its swampy setting, its ramshackle housing literally sinking below ground. In American Notes Dickens describes a place “reeking, everywhere with dirt and filth…. all that that is loathsome, drooping and decayed is here.” The Five Points personified a city so neglected by its government that garbage blanketed its streets. In the decades following Dickens’s visit, New York grew in a swirl of trash and worse, until citizen-reformers, a mustachioed engineer, and a very special uniform intervened with solutions that eventually reverberated worldwide.

Long before its funk repelled Dickens, the city was struggling with trash. When the Dutch West India Company established a trading post on Manhattan’s southern tip in 1624, New Amsterdam counted 270 residents. Forty years later a city of over 9,000, rough and lawless, perched on the edge of the known world. Early records portray a burg beslimed. House fronts featured privies. Horse manure, garbage, animal carcasses, and rubbish clogged the streets. In 1657, iron-fisted Governor Peter Stuyvesant imposed trash removal ordinances: “[H]enceforth no one shall be allowed to throw into the streets or into the graft [canal, running in the middle of the present Broad Street] any rubbish, filth, ashes, oyster-shells, dead animal or anything like it…Furthermore everybody is ordered, to keep the streets clean before his house or lot….” In 1664 England seized New Amsterdam, renaming the former Dutch holding for a venerable city at home. New York in the 18th century endured epidemics and high mortality. In the 1740s city government passed laws banning certain industries from locating near public water sources and more sharply regulating waste disposal. However, before administrators could implement many of these strictures, the city was swept up in the American Revolution, the arrival of national independence, and the rise of industry.

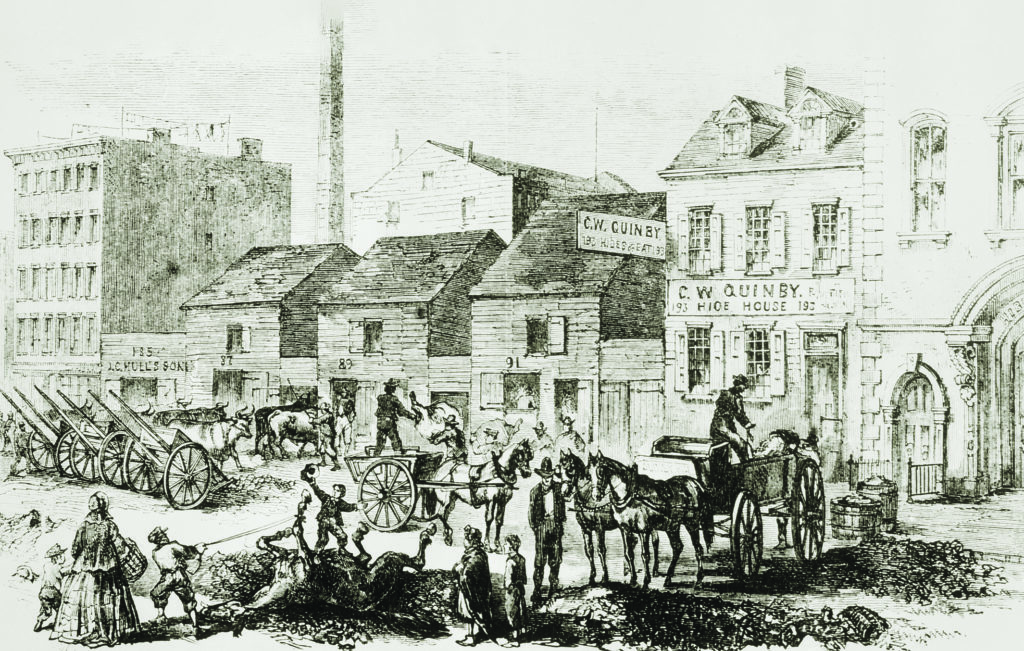

By 1860 the population exceeded 800,000, mostly living cheek by jowl along lower Manhattan’s 300-some miles of streets. Street sanitation was assigned to the Police Department, which was so inefficient at the job that builders of elegant brownstones installed stoops leading to second-floor entries to hoist occupants and visitors above the creeping decay. New Yorkers wore top hats and toted parasols less as fashion statements than as shields against whatever was being flung onto them from overhead. Street gutters carried offal into the rivers; wooden garbage boxes teemed. In a city dependent on the labor of horses, no rules applied to equine care. Riddled with disease, starved, and abused, animals that could weigh more than half a ton collapsed and died, often amid traffic, and were left to rot.

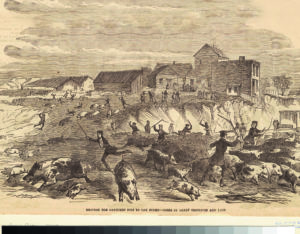

Alarmed by disease outbreaks and government ineffectiveness, wealthy reform-minded residents formed an independent civic action group. Working with

result was a slapstick roundup. (New York Public Library)

local physicians, the Citizens Association established the Metropolitan Board of Health, in 1866 declaring war on garbage. Dividing neighborhoods into districts, the board appointed physician-investigators to monitor and field thousands of sanitation complaints. Within four years groundbreaking sanitation laws were in place. The city banned the throwing of garbage and excrement into the streets. Ordinances stipulated that residents, landlords, and business owners had the responsibility to remove manure and refuse from streets and privy yards in front of their buildings. Building owners were to provide “suitable and sufficient” boxes, barrels, and tubs for garbage and metal receptacles for ashes. Butchers and tanneries no longer could use the streets as disposal sluices. In 1869 New York banned livestock from roaming loose inside the city limits.

In 1871, the sachems of the Democratic Tammany Hall machine, led by soon-to-be-jailed William M. “Boss” Tweed, outflanked the Citizens Association by redrafting the city’s charter, returning jurisdiction over health and sanitation to the Police Department. Service stayed slack through the decade. No new street cleaning inspectors were hired; the bureau’s clerical staff withered. Sanitation managers appointed by Tammany under the spoils system ignored their jobs. To keep their positions, department workers had to kick back a portion of their salaries to those no-show bosses. The city budget shortchanged street cleaning. Irate at Tammany, residents blamed sanitation workers, often heckling, throwing garbage, and even attacking them.

The 1894 mayoral election occurred amid popular ire fired by Tammany corruption and the previous year’s nationwide recession. Republicans and independent Democrats allied with reformers, women’s organizations, and the Citizens Association to run Ohio-born banker William Lafayette Strong. A novice chosen for his business acumen and spotless record, Strong embodied anti-Tammany fervor. The machine backed Macy’s owner Nathan Straus, who within weeks quit the race, hurriedly replaced by former mayor Hugh Grant, a pillar of scandal who lost to Strong by more than 40,000 votes. Once in office Strong moved to name as street cleaning commissioner prominent up-and-comer Theodore Roosevelt. When Roosevelt held out for the police commissionership, Strong recruited army veteran George E. Waring—a sanitation engineer who insisted on being addressed as “Colonel.”

William Strong came into office aiming to make the city cleaner and more honest. (New York Public Library)

Born in Pound Ridge, New York, in 1833, Waring came from a family that had made its fortune making stoves and farm tools; George grew up steeped in agricultural science. By age 20 he had written a manual aimed at young farmers and was working the lecture circuit, speaking at Grange halls across New England. In 1853 New York Tribune Editor-in-Chief Horace Greeley hired Waring to manage his farm at Chappaqua, New York. Greeley encouraged his new man to experiment with the latest drainage methods. Waring’s work soon caught the attention of civil engineer Egbert L. Viele, chief engineer on the construction of a huge new park at the heart of New York. Viele hired Waring to supervise drainage on the undertaking; he held that position until Central Park was finished. Park Superintendent Frederick Law Olmsted praised Waring’s hand in helping to create a sanitary urban park.

Waring enlisted in the Union Army in 1861. Under Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont, he rode as a major with the Frémont Hussars, assigned to contain Confederate guerrillas in Missouri, Tennessee, and Arkansas. The army promoted him to colonel. After Appomattox he returned to agriculture, in 1867 hiring on as a manager at the experimental Ogden Farm near Newport, Rhode Island. At Ogden Farm Waring continued his studies of agriculture, animal husbandry, and sewage engineering. He wrote treatises on waste and water management and public health, including the critically acclaimed Draining for Profit, Draining for Health.

His reputation in managing waste brought Waring opportunity in the form of disaster—a yellow fever epidemic ravaging Memphis, Tennessee. In 1878, fever was afloat on the Mississippi. An infected boatman evaded quarantine and entered the city, resulting in over 5,000 deaths and devastating the local economy. Declaring a national emergency, President Rutherford B. Hayes enlisted Waring. Applying his familiarity with the city from his wartime tenure, Waring persuaded city leaders to let him build an innovative wastewater removal system that separated tainted water from ordinary runoff. By October mortality among Memphians was down, public well-being had improved, and other towns were interested in Waring’s approach to sewerage. His Memphis achievements made him a leading expert in drainage and sanitation and launched him into a career as an international wastewater consultant. He had clients in London, Santiago, Cuba, and cities across the United States.

In a further gesture to morale, he outfitted the department’s rank-and-file in white trousers, jackets, and occasionally pith helmets, conveying an air of hygiene and authority but also approachability and accountability. The moniker “White Wings,” initially a catcall, quickly became a term of endearment. Under Waring the sanitation department rose to a standard unmatched by any government department in the nation.

Waring’s first test as sanitation commissioner came on the heels of his hiring. Within weeks of his starting work snowstorms pelted New York City. In the first five weeks of 1895 Waring’s street cleaners removed more snow, and at less cost, than the total of the previous five years. In March, Waring went after the Five Points. More than 50 years after Charles Dickens characterized the slum, it remained “as filthy a district as there was in the city.” The challenge of cleaning the grim neighborhood, whose inhabitants had manhandled street cleaners, went beyond garbage and refuse removal to scrap for the soul of New York. Waring strategized carefully, appointing as foremen for the task graduates of MIT and Harvard and requesting police escorts. Accompanied by two officers, Waring’s men descended into the Five Points and went to work. Within days the police were no longer needed and for the first time in Five Points history street surfaces there were visible.

The public and the press marveled at the changes Waring was wreaking. “Before” and “after” photos showed filthy thoroughfares and lanes made fresh. The commissioner made good copy, and reporters tagged along as he made his rounds, checking on everyday matters and inquiring about special projects. He used the press as a pulpit to preach the Progressive theory that residents had a duty to keep their city clean. Realizing that cleanliness began in the home, the department circulated guidance on sorting waste into four main categories: ashes, rubbish (dry waste), garbage, and street sweepings. City workers sorted these materials for conversion into grease, fertilizer, compost, and landfill. Unsalvageable waste was incinerated. To educate immigrants, the commission enlisted schools, settlement houses, and sanitation workers and with funding by philanthropists formed juvenile street-cleaning leagues whose motto was “Cleanliness is Catching.” The leagues encouraged thousands of children to adopt and circulate the slogan. League members participated in street cleaning competitions and enjoyed earning merit badges and participating in award assemblies and parades. Taking home what the program taught, children showed parents how to sort and dispose of waste.

In May 1896, Waring organized a showcase. Stretching from 59th Street to Madison Square, the parade down Fifth Avenue drew thousands for an afternoon of marching bands and 1,400 crisply uniformed White Wings moving in step with brooms behind Waring, in military uniform and white helmet, astride a fine brown horse. The following year a similar spectacle down Eighth Avenue to Madison Square drew more than 100,000 onlookers and rhapsodic coverage. The Daily News noted that Waring’s “mustache was more carefully waxed than ever….” And in a column of verse dedicated to the street cleaners, the New York Press published “The March of the White Brigade,” the last stanza proclaiming “Because you made the first crusade, for cleanliness and beauty,/Which are the next, says holy text,/To godliness and duty.”

In 1897, Waring told McClure’s Magazine his teams were sweeping 924 miles of street a day. Prior to his arrival as sanitation chief “the streets were almost universally in a filthy state,” he said. “Rubbish of all kinds, garbage, and ashes lay neglected in the streets and in the hot weather the city stank with the emanations of putrefying organic matter.”

The department was spending 17 percent more under his leadership, but that rise was less than increases in years past, he maintained. And his budget was not lining city

officials’ pockets but underwriting the department’s work, which improved public health and civic morale, he said.

Cleaner streets and luminous press coverage could not keep Tammany from elbowing its way back into power. The sachems had fought Waring at every turn, accusing him of overspending and mocking his ideals, which the bosses said amounted to having schoolchildren give horses fruit skins rather than toss them onto the sidewalk. Tammany criticized Waring for overreach, citing examples of juvenile street-cleaning leaguers issuing citations and tenants threatening to report their landlords for not cleaning buildings. In November 1897, Tammany candidate Robert van Wyck was elected mayor, ousting Strong and his reformist platform. The Tammany bosses understood that to hold onto power they had to change the way they did business. Within months, Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx, and Staten Island consolidated into the modern municipality of New York City. This new New York needed more infrastructure and services than ever before and if Tammany could not deliver, voters would boot the sachems in favor of reform candidates.

Waring was out of work, but civil service still called. In spring 1898 the United States and Spain went to war. By summer’s end thousands of American troops were in Cuba. Tropical diseases, including yellow fever, whose mode of transmission—mosquito bites—was unknown at the time, were striking down more American soldiers than the Spanish (“Rough Ride,” February 2018).

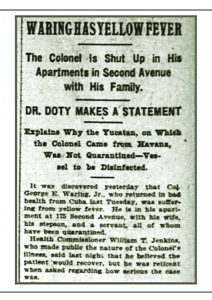

Alerted to Waring’s work in Cuba, President William McKinley named him to chair a commission assigned to study public health on the island. In October Waring spent two weeks touring Cuba’s capital, Havana, and outlying army camps, drafting recommendations for a program of sewage and street cleaning. He returned to New York on Tuesday, October 18. The next day he began feeling yellow fever symptoms.

On Saturday, October 29, Waring died—“an irony of fate,” The New York Times said. He was 68. In New York, thousands paid tribute to the man who had made their city a better place to live. Although the White Wings eventually passed into history and Waring did not solve New York City’s trash problems, the colonel’s systems and structures helped drive municipal reforms worldwide, eventually leading to the construction of countless miles of sewers. Praising “Colonel Waring’s broom that first let light into the slum,” muckraking photographer Jacob Riis said, “His broom saved more lives in the crowded tenements than a squad of doctors.”

This story appeared in the August 2020 issue of American History