Charles Campbell believed in the winged mammals’ voracious appetite for mosquitoes

During the nation’s formative years, malaria—from the Italian mal’aria for “bad air,” reflecting medieval assumptions about the disease’s origins—scourged a vast swath of the United States stretching north from Texas and Florida to Virginia and Illinois, and as far west as Montana. Malaria, with its fevers, chills, sweats, headaches, and nausea, sapped millions of vitality. Left untreated, malaria could and did kill.

In 1800s America, malaria exacted a cruel tax: $100 to $250 million yearly in treatment, lost wages, and diminished productivity. Into the 20th century, as much as 80 million fertile acres lay fallow because malaria rendered farmland uncultivatable. Quinine, from the bark of a Peruvian tree, was known to suppress the disease. Nobel Prize-winning discoveries in 1880 that a parasite caused malaria and in 1897 that mosquitoes transmitted that disease clarified malaria’s what and how, but did not show a way to prevent the disease until, for a brief period, a Texas physician seemed to have the cure—bats.

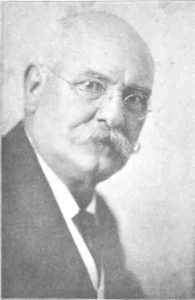

In 1902, San Antonio, Texas, was rebounding from a typhoid epidemic. Among those who helped quell the outbreak was bacteriologist Charles A. R. Campbell, 37, who insisted San Antonio’s water supply be “purified” by lining its reservoir in cement, reducing the incidence of typhus. Besides being San Antonio’s chief bacteriologist, Campbell, an infectious disease specialist, had a private medical practice. With the epidemic over, he turned his attention to his town’s perennial medical problem: malaria.

San Antonio, home to 150,000, stood less than 150 miles from the Gulf of Mexico, offering a steamy environment perfect for breeding insects. By 1902, it was widely understood that malaria was transmitted by the female mosquito of the Anopheles genus. Unfortunately, 30 to 40 species in the genus carry the disease. Females lay eggs in stagnant water. A two-week incubation period follows during which the eggs hatch, become larvae, then pupae and finally adults, which live for a destructive week or two.

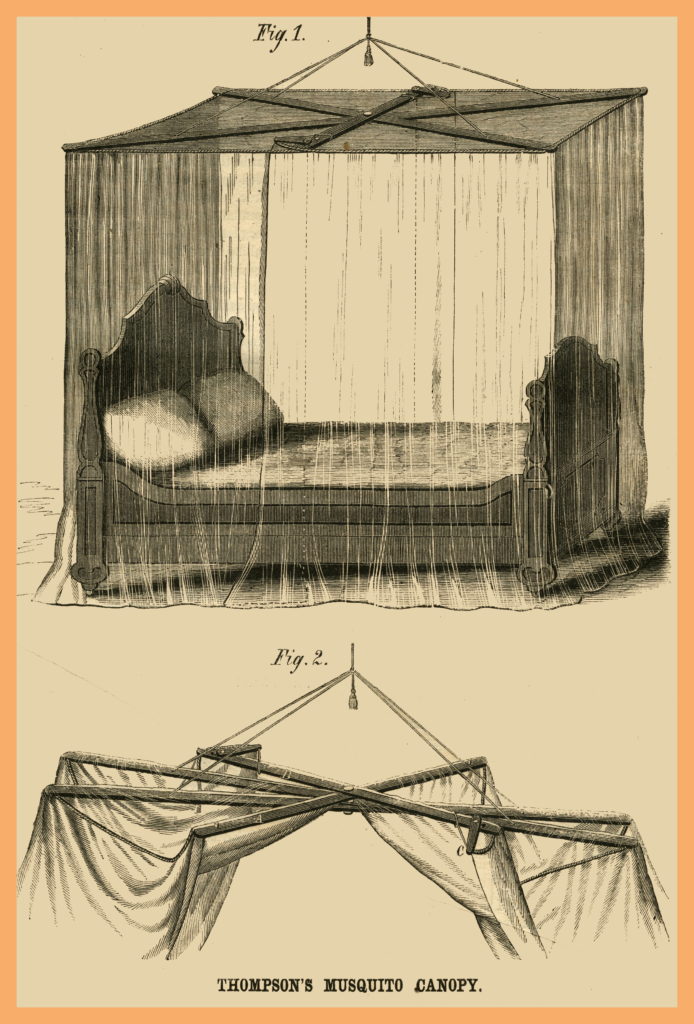

The challenge was keeping mosquitos at bay. Preventive steps included insecticides, wiping out breeding grounds by draining swamps and marshes, killing larvae by pouring oil onto stagnant water, and screening windows and enveloping beds with netting that kept insects away. But mosquito control was hard on the city budget; screens and nets often cost more than poor residents could afford.

Besides mosquitos and other biting insects by the billions, San Antonio had another species in profusion. The vicinity was home to an unusually large bat population. Bracken Cave, just northeast of town, harbored millions of bats, drawn by the area’s assortment of flying insects. Besides Bracken Cave there were eight other major caverns conducive to roosting (even today, San Antonio is home to an estimated 100 million bats, the world’s largest census of the species. The most common, the little brown bat and the Mexican free-tailed bat, live 40 years. These hearty predators can consume 1,000 mosquitoes an hour, ideal for testing Campbell’s hypothesis, inspired in part by a trip he took to the Arctic where he found “the mosquitoes more numerous and fierce than in any other country,” coincidentally realizing “it might be a greater boon to mankind to extirpate the mosquito than to stamp out tuberculosis.”

Where the public saw dirty, disease-bearing harbingers of evil, Campbell saw a mosquito control tool. Enough bats in the right location could turn back the mosquito hordes. “Can bats like bees be colonized and made to multiply where we want them?” he wrote. “This would be no feat at all! Don’t they live in any ramshackle building? They would be only too glad to have a little home such as we provide for our birds.”

So avid a bat advocate that he recommended the animals as pets, Campbell wondered how best to breed and house them for mosquito-control purposes. First, he experimented at home designing and constructing birdhouse-like roosts that he lined with guano-laden cheesecloth he thought would-be tenants would find homey. To test his theories, he placed roosts in likely settings like caves and under bridges, as well as his backyard. When not one bat took up residence, Campbell concluded that he was thinking too small; perhaps bats preferred larger enclosures. In 1907, he spent $500 building a “Malaria-Eradicating Guano-Producing Bat Roost” at a U.S. Department of Agriculture experimental farm near his home.

The dimensions of Campbell’s first wooden roosts are lost, but the design slowly evolved into something that suggested a decapitated church steeple fitted with a lantern to draw bats and their prey. Inside were shelves intended for several hundred roosting bats. For “the delectation of the intended guests,” Campbell hung three hams. Sparrows flocked to the roost, but no bats—until Campbell trapped 500 of the furry little creatures and moved them in. The press-ganged predators fluttered off, never to return. Campbell scrapped the failed roost, and took off for West Texas, where he observed bats in the wild, deciding that artificial bat roosts would do best by water because that’s where the most mosquitoes were.

In 1911, Campbell found his ideal test bed: 900-acre Mitchell Lake, less than ten miles south of San Antonio. Originally a naturally occurring body of water, the lake now received 10 million gallons a day in raw city sewage. The lake, 25 feet at its deepest, was home to clouds of rapacious mosquitos that drove local livestock mad enough to break through barbed wire to escape, and tenant farmers to coat themselves in mud before dressing for work. Upon examining 87 members of Mitchell Lake farm families, Campbell found that 78 had malaria—an infection rate of 89 percent.

Two abandoned buildings nearby hosted bat colonies, suggesting the winged mammals found the vicinity hospitable. Nearby, Campbell had work crews install four concrete pillars, each ten feet high. Atop this foundation, he built a roost modeled on the one he’d built at the experimental farm. This $2,500 wood structure, its sides louvered to let dwellers in and out, was 12 feet square at its base, tapering to 6 feet at the top with a hinged floor that allowed harvesting of accumulated guano. Once in place, the 30-foot tall contraption put some observers in mind of a blade-less windmill or, considering its clapboard siding, louvers, and decorative cross, a chapel.

Campbell unveiled the Mitchell Lake roost on April 2, 1911. On Independence Day, he was on site at dusk hoping to see bats swarm out of his invention. They did, but the colony was small, and the resident bats only needed five minutes to disappear. To boost his roost’s population, Campbell decided to empty those abandoned, bat-rich buildings across the way. He sent a boy into the old houses at 4 a.m. one morning with a hand-cranked Victrola and a recording of Mexico City’s Police Band performing the “Cascade of Roses” waltz on trombone, piccolo, trumpet, clarinet, and drums. Within two nights the bat colony had taken up residence in the new roost. The relocated bats, eventually 250,000 strong, soon needed two hours to depart the roost, often with tourists on hand for the show. Assuming each bat consumed 3,000 mosquitoes a night, Campbell claimed his flying friends were reducing Mitchell Lake’s mosquito population by 750 million per evening. In 1913, when Campbell examined his tenant farm study subjects, he didn’t find a single new case of malarial infection.

To further his program, Campbell pressed San Antonio officials to outlaw the killing of bats in town. A 1914 city ordinance prescribed a fine for chiroptericide of $5 to $300 depending on the number of dead bats. The same year, Campbell obtained U.S. Patent No. 1,083,318 for bat roost shelving. In 1916, San Antonio allocated $3,000 to build a municipal bat roost in the city’s Mexican quarter. A sign on the rig in English read, “This structure is a Bat Roost. A home for bats, and belongs to the City of San Antonio. Bats are one of man’s best friends because they eat mosquitoes and mosquitoes cause chills, fevers and other disease. By protecting bats, you protect your fellow man. All persons are warned not to in any manner disturb this roost under the penalty of the law.”

However, many San Antonians hated the notion of neighborhood bat towers. To win converts, Campbell undertook a program of education, conservation, and colonization. He became the species’ ambassador, calling bats “man’s best friend.” He even lobbied to extend San Antonio’s bat-killing ban to all of Texas.

If Campbell was anything he was a master at promoting himself and his work. Passionate and charming, with a fringe of white hair that matched his fluffy mustache, the chunky Campbell perched wire-rimmed spectacles on an oversize nose—Santa Claus as Bat Man. His stature at the height of San Antonio society was a major asset. “Dr. and Mrs. Campbell are prominent socially, the hospitality of the best homes …being cordially extended to them,” a 1907 History of Southwest Texas noted. “He practices along modern scientific lines, keeping in touch with the most advanced thought of (his) profession…(and) has done important public work…which entitles him to the gratitude of every resident of San Antonio.”

Campbell’s ideas were unconventional for the time. In Scientific American, he wrote, “The bat will attack only such insects as emit certain tones in their flight…tones emitted by mosquitoes range from staff D, to F, G, and higher (which bats find attractive) …insects emitting a tone lower than C natural are avoided by bats.” Researchers did not identify echolocation, the bat’s navigating and hunting tool, until 1938, but much earlier Campbell was noting with a degree of prescience that “a mosquito must stop its flight to protect itself for the vibration of its wings…attract the bat’s attention.” Campbell also perceived the role of mass transportation in spreading malaria. As roads penetrated once inaccessible land, the parasite found new vectors, he pointed out.

In March 1917, Texas Governor William P. Hobby signed a state law that made it a crime to kill or hurt a bat. A year later, San Antonio Mayor and Campbell ally Albert Steves Sr., built a bat roost at his home in Comfort, Texas. The state also built a Campbell-style roost at the Southwestern Insane Asylum outside San Antonio, whose wealthy new suburb, Alamo Heights, raised $2,000 through public subscription for a Campbell bat tower. Located on the grounds of a school, it was indication of Campbell’s success in rewiring Texans’ attitude toward bats. And one of Campbell’s innovations was paying off literally; the 1918 guano yield at Mitchell Lake exceeded two tons, bringing $300 he put toward maintenance and more roosts.

In 1919, the Texas legislature nominated Campbell for the Nobel Prize in medicine. The honor eluded him—coincidentally, no one won a Nobel in medicine in 1919—but his bat roosts continued to gain popularity. When the Illustrated London News carried an image of the San Antonio Municipal Bat-Roost, Europeans took notice. In 1924, two Campbell roosts went up in Rome’s notorious marshes. Another was constructed in Austria. Back in the United States, a developer outside Tampa, Florida, built a roost near the Hillsborough River using plans from Campbell. In 1925, Campbell published Bats, Mosquitoes and Dollars, a manifesto longer on pluck than science. In 1929, the largest landowner in the Florida Keys erected a Campbell roost on Sugarloaf Key. And in 1930, another wealthy individual built a Campbell in Orange, Texas.

Leaving a theater in 1931, Campbell, 66, tripped and injured his leg. Blood poisoning set in and, despite two surgeries, he died. All through the years, the Campbell family had been harvesting and selling guano from the Mitchell Lake roost. Son Mitchell carried on this business until this death in the 1940s, whereupon his wife took over.

Without Campbell’s ebullient ballyhoo, his roosts’ mystique faded. Many, like the Sugarloaf Tower, failed to attract bats. And even when a roost did fill with fluttering inhabitants, as at Mitchell Lake, there’s no conclusive proof that its presence meant less malaria risk.

The equation is simple, said bat expert Gary F. McCracken, a professor at the University of Tennessee specializing in the dietary habits of the Brown and Mexican free-tailed bat. “The dietary habit of these bats has been studied extensively,” McCracken said. “They eat very few mosquitoes.”

No one ever replicated Campbell’s Mitchell Lake data, and even when he was alive his claims engendered skepticism. L.O. Howard, chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture Bureau of Entomology, said in 1926, “I have been unable to substantiate the claims made by Doctor Campbell as to the value of bat roosts in the great reduction of the mosquito population of a given locality.”

Campbell never advocated bats as a sole means of malaria control, but argued that bats accomplished at least as much as human-led control efforts, albeit with less expense and effort. And he did not profit on his roosts—though he did charge $175.00 for his bat bait recipe. Though Campbell kept his recipe secret, scientists speculate that it was a combination of bat guano and the ground-up sexual organs of female bats.

More promoter than scientist, Campbell drew most of his invitations to spread his bat gospel not from technocrats but fellow boosters representing civic and business in places like Houston, El Paso, Miami, and Key West. Those who did build Campbell roosts tended to be developers needing a gimmick to sell houses in mosquito-ridden areas and wealthy individuals inclined to status display. Insecticides trumped bats at mosquito control, and medical malaria-fighting methods improved dramatically.

But the good doctor is not entirely forgotten. A copper bat adorns his San Antonio gravestone. And there’s also the question a letter writer posed: “Once you’ve got rid of the mosquitoes, how do you get rid of the bats?”

John J. Geoghegan writes about unusual inventions that fail in the market despite their innovative nature.

_____

Going Batty

Ever the booster, Charles Campbell claimed to have put up more roosts than were built. News reports of the day tally 16: six in Texas, two in Florida, one in Mississippi, at least one each in Austria and Panama, and as many as six in Italy. There may be more; Belgium encouraged its colonies in the tropics to build roosts but knowing Dr. Campbell’s penchant for promotion there may well be less. In the United States, roosts still stand at Sugarloaf Key, Florida, in Comfort, Texas, and at Shangri La Botanical Gardens and Nature Center in Orange, Texas—the first two on the National Registry of Historic Places. No San Antonio bat-roost survives. Vandals destroyed the last specimen in 1969. Fundraising is under way to replicate Florida’s much-missed Hillsborough roost, which was torched in 1979. America’s most successful artificial bat roost has nothing to do with Campbell or his theories. Located at the University of Florida in Gainesville, the dual roost was built in 1991 houses up to 300,000 bats—not to fight malaria but to keep the critters away from other buildings on campus. —John J. Geoghegan