“What are you guys doing in Greenland?” asked a radio operator at Ladd Field near Fairbanks, Alaska. “We came down to shoot a few polar bears,” replied radio operator Tech. Sgt. Robert Leader, whose Boeing B-29 Superfortress had just belly-landed on a frozen lake about 700 miles from the North Pole.

It was shortly after midnight local time on Sunday, February 23, 1947, and Leader and the rest of the crew were in the middle of what turned out to be a rather long weekend.

The Cold War had begun in earnest less than a year after the end of World War II. Operating from Ladd Field, the 46th Reconnaissance Squadron was tasked with investigating Soviet offensive and defensive capabilities in northern Siberia. The United States was also racing to map the Arctic and perfect methods of navigating in polar regions.

The 46th flew its first mission from Ladd Field in August 1946, and on October 16, a B-29 took off from Ladd and flew over the North Pole for the first time. By the following year, polar overflights had become almost routine. The 46th had its fair share of more exciting routes, such as those that ran along the Arctic coast of Siberia, where crews were instructed to keep their planes just within international airspace and monitor Soviet radar to see how well they could detect U.S. aircraft. On more than one occasion, the Soviets scrambled fighters in response.

On February 20, 1947, at 2:20 in the afternoon, one of those more or less routine flights took off from Ladd Field. The B-29 making the flight (an F-13 variant modified for photoreconnaissance), serial No. 45-21768, had been dubbed the Kee Bird. A kee bird is—at least according to soldiers stationed in Canada and Alaska—an ugly and unintelligent bird that spends its winters in the Arctic calling out “Kee-kee-kee-rist, it’s cold!”

The crew of 11 were part of Project 8, the most highly classified section of the 46th. Their mission was to fly due north, circle the pole and return to Ladd Field. They were to maintain radio silence once they crossed Point Barrow, Alaska’s northernmost point. Kee Bird was carrying enough fuel for about 26 hours of flight, having been retrofitted with additional fuel tanks in its otherwise empty bomb bay.

The assigned photo-gunner, Staff Sgt. Robert Zwiesler, had a cold, and Staff Sgt. Ernest Stewart was tagged that morning to replace him. Stewart was glad to join the mission as it was getting on toward the end of the month and he needed some time in the air to draw flight pay for February.

Lieutenant Vernon Arnett was assigned as Kee Bird’s pilot. Arnett and flight engineer 2nd Lt. Robert Luedke had already had one adventure together. They had both been onboard We’ve Had It, a B-29 that crashed shortly after takeoff just over two months earlier. Walking away from that crash had earned Luedke the nickname “Lucky.”

After ground crewmen tightened one of the engines’ propeller blades and navigator Lieutenant Burl Cowan grabbed the standard-issue map kit, Kee Bird took off. The flight out was relatively uneventful. The weather was clear when the B-29 flew over Point Barrow at 6 that evening on a direct heading for the North Pole.

They crossed the pole at midnight and turned back toward Alaska. About 250 miles south of the pole, the weather closed in around them. Up to that point they had been able to take periodic observations to correct the gyroscopic compass, reportedly part of an experimental navigation system.

In theory, once set in motion, a gyroscope in a gimbal assembly will always point in the same direction, regardless of either its position on the Earth or the motion of the Earth itself. This makes it an ideal navigational tool, especially in areas where magnetic compasses are ineffective. In practice, friction within the gyroscope and gimbals causes the axis of the gyroscope to precess, or move in a circle, over time. If the rate of precession of the gyroscope is known with some certainty, the navigator can correct the heading without taking visual bearings.

Cowan didn’t trust the gyroscopic compass, and after about 45 minutes in the cloudbank, he suggested that they climb out of the overcast and take new bearings. Arnett agreed, and Kee Bird broke out of the clouds at about 24,000 feet. It took them about half an hour to get free of the weather because Arnett was trying to conserve fuel—Kee Bird had been performing sluggishly throughout the mission.

Kee Bird drifts off course

By the time the B-29 was in a position to take bearings, it had drifted far enough east and had been in the air long enough that darkness was giving way to twilight, and Cowan could not get a fix on any of the navigational stars on his charts. At his suggestion, they remained above the cloud cover hoping to establish their location using the sun after it rose. However, the sun barely cleared the horizon before it began to set again, and at such a low angle, atmospheric distortion made reliable sighting impossible. With Kee Bird again in twilight, Cowan told Arnett and copilot Lieutenant Russell Jordan that he couldn’t give them a fix on their location or recommend a heading.

The crew’s best hope at this point was to make landfall and then identify their location based on the radar returns. If they were on course, or close to it, they’d reach land at about 6:30 in the morning. Instead, at 5 a.m., radar observer Lieutenant Howard Adams told Leader that there was land about 100 miles distant, 165 degrees off the plane’s current heading. Leader had to pass the message on to navigator Cowan, and according to the radio operator, “He was not a happy camper.”

Cowan and the assistant navigator, Lieutenant John Lesman, went aft to the radar station and confirmed what Leader had reported. They saw returns indicating a rugged and mountainous coast. This was enough to convince them that they were well and truly off course. The Alaskan coast in the vicinity of Point Barrow is fairly flat, with the Brooks Range some distance inland.

There was no point in referring to Cowan’s map kit, which charted only the Alaskan coast. An emergency kit, prepared by Project 5, included maps of the Canadian archipelago as well as what was known of the Siberian coast, but that kit was not standard issue. Furthermore, radar operators were kept within individual project assignments, so Adams was looking at terrain he had never seen before, since none of the Project 8 missions deviated from the course covered by their charts.

With neither charts nor experience to guide them, at a little before 8 a.m. Arnett authorized Leader to break radio silence and contact Ladd Field to request assistance.

At first, Leader couldn’t reach Ladd directly, and had to interrupt the voice traffic of the civilian air controller in Barrow. According to Leader, “He broke off his own traffic to listen to my tale of woe” and relayed the message to Ladd Field.

When Leader got in touch with Ladd, he requested that they turn on their directional finder. They asked him if it was just for practice, and when he informed them it wasn’t, they told him the directional finder was offline for maintenance.

While this was going on, copilot Jordan was trying to use the radio compass. He’d picked up a strong, steady beam that did not broadcast any identifying information. Arnett suggested that they follow the beam and then bail out when they hit the “cone of silence” directly over the station broadcasting the beam. As they were currently flying above an undercast with no idea of the terrain below it, Jordan told Arnett he’d rather stay with the plane.

It was later discovered that the Soviets had been sending radio signals over the Arctic to lure U.S. planes into Russian airspace.

Hope from kfar

Giving up on the unidentified station, Jordan started searching for another station that they could use to set their course. Eventually, he picked up KFAR, a radio station in Fairbanks that many pilots used for navigational purposes. The KFAR signal would lead them right back to Ladd Field.

About half an hour after locking onto KFAR, the signal started to wander and then it disappeared entirely. It turned out the crew had not been following the signal from the KFAR antenna; they had been locked onto a “skip wave” reflection of the signal off the ionosphere.

At this point, the crew had no better option than to look for a place to set Kee Bird down. They had been flying a variety of headings in response to the radio compass and the terrain below and were running out of fuel.

Jordan was still trying to pick up the KFAR signal at about 10 a.m., Alaska time, when he spotted a saucer-shaped depression ahead, just off his side of the B-29. He pointed it out to Arnett, who decided to descend and have a closer look. They soon realized this was their only shot at a soft landing when Arnett banked the bomber about 100 feet above the ground and the engines started to cough from a lack of fuel.

Leader was on the radio with Ladd all this time and as they came in for their first pass at the landing site, he told Ladd, “We’re heading into the sun and we’re going to set her down.” He then locked down the radio’s Morse code transmission key to transmit a steady signal that Ladd could hopefully get a directional fix on.

In what turned out to be the first positive development for the Kee Bird crew, Ladd Field was able to pinpoint the direction of the Morse signal at 46 degrees off true north.

With sufficient time to prepare for an emergency landing, the crewmen took several measures to raise their odds of survival. Emergency gear was moved to the exit hatches, so that in the event of a fire it could be grabbed on the way out. All of the hatches were opened to prevent a crash from deforming the doors and trapping the crew inside. Arnett decided on a wheels-up landing because they had no idea how deep the snow was or what exactly they were landing on. As a final precaution, engineer Luedke threw the master bar, cutting off the plane’s electricity—a safeguard against a spark-induced fire—as soon as Arnett and Jordan no longer needed it to land the plane.

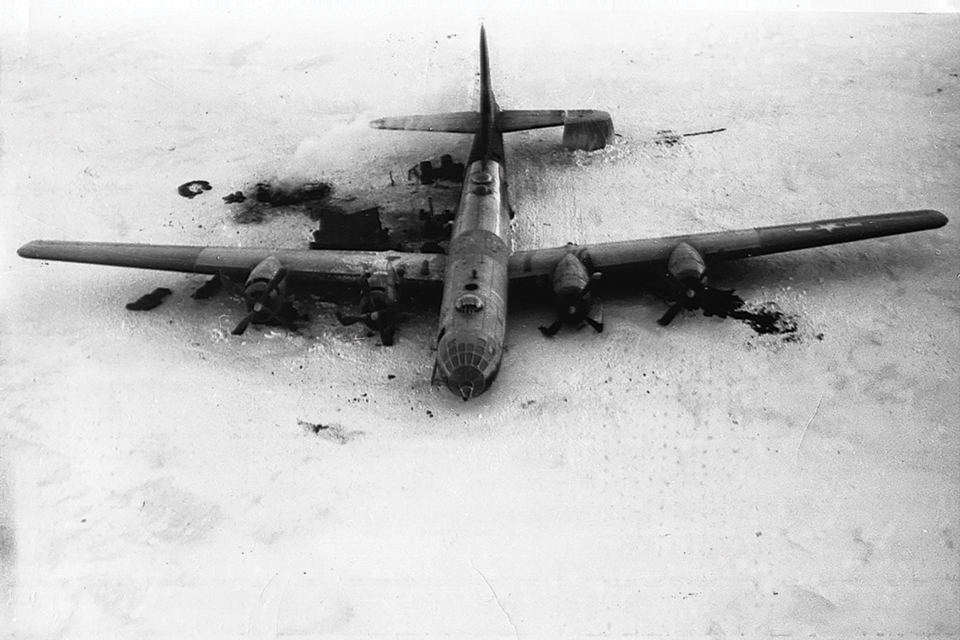

A little after 2 p.m. local time, not quite 21 hours after takeoff, Kee Bird touched down on an unnamed frozen lake, sliding a good distance on the ice before coming to a jarring halt. None of the crewmen were injured, although photo-gunner Stewart was so nervous when the plane came to rest that he couldn’t unfasten his safety harness. Fellow gunner Master Sgt. Lawrence “Yardbird” Yarbrough told him to calm down, but that seems to have been the extent of the drama associated with the landing.

50 below zero on the ground

The first man out of the B-29, another photo-gunner, Staff Sgt. Paul McNamara, got down on his knees and made the sign of the cross. When he stood up, he was heard to say, in defiance of obvious evidence to the contrary, that this was something that only happened to other people.

It was at least 50 below zero on the ground in Greenland, and the crewmen quickly availed themselves of Kee Bird’s mukluks and other cold weather gear. They took several practical steps after landing. Luedke and Yarbrough immediately drained the oil from two of the B-29’s engines before it froze inside them. The oil froze solid on the ground, and the crew cut it up into blocks to use to fuel fires. They assembled a makeshift stove to thaw out the bomber’s auxiliary generator, without which they wouldn’t have been able to use the radio. When it finally fired up, Jordan described it as the sweetest sound he’d ever heard.

The first plane to participate in the search and rescue effort took off at 1:40 p.m. Alaska time, just a few hours after Ladd had gotten a directional fix on Kee Bird’s location. When that B-29, piloted by Captain Richmond McIntyre, reached its designated search area over MacKenzie Bay, just across the Canadian border, Ladd radioed that Kee Bird was on Borden Island, 600 miles farther out on the same heading.

Meanwhile, back at the landing site, Cowan and Lesman were finally able to determine their approximate position based on the stars. They were in Greenland about 250 miles northeast of Thule, a Danish weather station. This information was radioed to Captain McIntyre’s B-29, which made three passes over northern Greenland, but the crew didn’t sight Kee Bird before they had to head back to Ladd.

While McIntyre’s B-29 was over Greenland, a second Superfortress piloted by Captain Donald Allenby took off from Ladd just before midnight Alaska time on February 21. Meanwhile Leader was in constant contact with the Thule weather station and the B-29 search planes. When Allenby’s B-29 got to Greenland at about noon local time on the 22nd, Kee Bird’s crew reported that they were under a high thin overcast. Allenby noticed that the only local cloud cover was over about a 40-square-mile area. Shortly afterward, he sighted Kee Bird and made several passes to drop supplies and photograph the vicinity for rescue planning purposes.

Back at Ladd, a variety of rescue options were considered before they decided to send a Douglas C-54 to pick up the crew and fly to Thule, as the transport couldn’t carry enough fuel to make a round trip. The rescue plane touched down on the lake next to Kee Bird at about 8 a.m. local time on the 24th.

Landing the C-54 on the frozen lake next to the B-29 wasn’t a problem. Taking off was. They would have to use JATO (jet-assisted takeoff) and leave behind their own emergency equipment to get airborne. While they were on the ground, another B-29 circled nearby, ready to assist if they encountered any difficulties during takeoff or on the flight to Thule.

After a short, uneventful flight to Thule, the Kee Bird and C-54 crews were treated to a steak dinner by the Danish staff at the station. The next day Kee Bird’s crew was put on a plane to Westover, Mass., for medical attention, provided with sleeping pills and told not to talk to the press until they’d been given a cover story.

Arnett and his crew had spent three days on the ice in Greenland and never once saw the sun.

efforts to recover kee bird

Kee Bird would lie on that Greenland lake for 48 years.

All told, Boeing built almost 4,000 B-29s, but by the late 1980s only 22 were left. Well, 22 and Kee Bird. In 1989, a retired pilot in Florida, William Schnase, tracked down Luedke and pitched the idea of salvaging Kee Bird. After all, it hadn’t been damaged during the landing beyond bent props and should have been well preserved in the Arctic cold. But midway through the project. Luedke had back surgery, and he subsequently lost touch with Schnase.

In July 1994, a salvage operation led by famed racing pilot Darryl Greenamyer and funded by a group of California businessmen set up camp in Greenland seeking to repair Kee Bird, fit the B-29 with four new engines and props and fly it off the lake. The team’s efforts, documented by a film crew, were not without a human cost. Late in the year, chief engineer Rick Kriege developed a blood disease, and he couldn’t be evacuated because the 1962 de Havilland Caribou the salvage crew was using to access the site had engine problems and wasn’t flightworthy. By the time it was repaired and Kriege was evacuated to a hospital in Canada, he was bleeding internally. He died two weeks later.

In the spring of 1995, the salvage team reunited the surviving Kee Bird veterans, brought their documentary film crew back to Greenland and attempted to fly Kee Bird off the lake. However, someone left the auxiliary generator running, the same one the crew had thawed out back in 1947. A can that reportedly had been left hanging over the generator to provide fuel came loose during their bumpy taxi across the lake’s surface, spilling gas onto the hot generator. The resulting fire rapidly destroyed the airframe, and when efforts to extinguish the flames failed, the team was forced to watch their hard-fought dream go up in smoke.

What’s left of Kee Bird is now embedded in the ice. Its last known visitors were a crew from a Danish mineral exploration company that took a detour to visit the site by helicopter in September 2014. On a beautiful fall day, Michael Hjorth, his crew and a couple of Air Greenland pilots landed at the far end of the lake and walked over to Kee Bird. As might be expected, Hjorth reported that the wreck was in bad condition. The cockpit had sunk into the lake and the tail section was in front of the plane, upside down, likely blown there in a storm.

And there Kee Bird will undoubtedly remain—a Cold War relic in a very cold place.

Richard Jensen is a writer and historical preservation consultant based in Sioux Falls, S.D. Further reading: Hunting Warbirds, by Carl Hoffman.

This feature originally appeared in the January 2020 issue of Aviation History.