Among the densely wooded paths of Nuremberg’s Südfriedhof cemetery lies a silent meadow where 5,085 forgotten men rest in mass graves, overlooked in the foreign land where they were brought to die. Victims of forced labor and slavery, they number among millions of forsaken dead scattered throughout 3,500 known burial sites in Germany.

Once they were soldiers of the Red Army. Yet, unlike their surviving comrades celebrated in Russian victory parades and feted with heroic sculptures, these captives were disregarded both in Germany and in the former Soviet Union.

Due to discriminatory treatment—which resulted in the deaths of over 60 percent of Red Army soldiers captured by the Germans during the war—Soviet POWs “had to fight for survival under catastrophic conditions,” wrote Hanne Lessau of the Museen der Stadt Nürnberg. Hoping one day be reunited with their families, these men showed courage in their struggle to survive. Some prisoners, like the pilot Mikhail Devyatayev, rose to extraordinary feats of bravery to sabotage German plans and escape. Yet Joseph Stalin and his regime condemned these survivors as traitors and cowards upon their repatriation. Ostracized by society, many were sentenced to die in gulags or ended their days in abject poverty.

“The Soviet prisoners of war are to this day hardly recognized as victims of National Socialism: the general public does not know that 3.3 million soldiers died in German captivity,” according to Dr. Ruth Preusse of the Haus der Wannsee Konferenz.

Preusse is the curator of an online exhibit, “An Unrecht Erinnern” (Reflect on Injustice), created in partnership with Memorial International Moscow and other human rights organizations. The exhibit makes use of videos, photos, documents, maps and interviews to educate members of the public about the abuse of Soviet prisoners of war.

Unlike many Western European POWs, Soviet prisoners were treated brutally by their German captors. Their mistreatment was largely due to racism, according to Preusse.

“Under international law at that time, prisoners of war had the right to be treated in the same way as German soldiers with regard to food, accommodation and medical care. They had the right to correspond with their families and engage in cultural activities. Western prisoners of war were allowed to do all of this—only Soviet and, later also the Italian military internees, were denied,” said Preusse.

An Invisible Majority

Captured Soviet soldiers were treated as slaves. Penned together in open fields and without food, drink or shelter, they were forced to work in armaments factories to create weapons for their enemies. They were tortured in medical experiments. In Nuremberg they toiled at the Nazi Party Rally grounds to build Adolf Hitler’s Congress Hall, intended to be twice the size of Rome’s Colosseum. They were forced to clean rubble from streets. Abuse of Soviet prisoners was an open secret.

“The Soviet prisoners of war forced to work in Germany were visible everywhere in everyday life,” said Preusse. “They worked in agriculture, in industry, at large locations and, although segregated from the rest of the population, even in small villages. People saw how they were treated. Many enriched themselves from their labor.”

After a bombing raid in Nuremberg, a group of Russian slave laborers saved an injured nine-year-old German boy from the ruins of a hospital—frightened and buried under rubble, the young Otto Mehl was pulled from certain death by the hands of men who were supposed to be his enemies. “I was happy that it [the bomb] didn’t get me,” he remembered many years later, “and I had the impression that the Russians were also glad to have found us alive.”

Yet, like many Soviet POWs, the identities of Mehl’s rescuers remain lost to history as the soldiers were not treated with individual dignity. It is “rare to find so much as a single personal photo” of any of the 10,000 Soviet prisoners detained in Nuremberg, according to Lessau. They had been characterized by Nazi propaganda as “monsters.”

“Nazi propaganda staged this war as a ‘battle between two worldviews.’ Additionally, Soviet citizens were deliberately portrayed as ‘subhuman’ and racist patterns of thought were established,” said Preusse. “Hatred for different reasons combined into a literally fatal mix.”

“The Wehrmacht systematically let them starve to death or die of disease; political commissars and Jews were shot after being captured. Those who survived the first provisional camps were intended to die by forced labor—all of that was and is in violation of international law and also against their own regulations. I wanted to clarify this in Germany,” said Preusse, speaking of her reasons for creating the exhibit.

“In Russian-speaking countries, the exhibition is intended to help people searching for information about the imprisonment of their relatives in the German Reich, for example in specific locations.”

Despite information available in Germany about the fates of prisoners, many surviving relatives and descendants of POWs across Russia and Eastern Europe do not know where to look for lost loved ones. To those they left behind, sons, husbands, fathers, brothers, and uncles simply disappeared off the face of the earth after Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941.

Scattered across German cemeteries, many Soviet soldiers remain stranded even in death.

Finding Kyrill Kasyanov

His family assumed he had died fighting on the frontlines. His wife imagined sometimes that she could have saved him, and never forgave herself for not being able to. It took 60 years after he bid his family a solemn last goodbye, warning them he did not expect to return from war, for the memory of Kyrill Vasilyevich Kasyanov to be laid to rest with his surviving family.

“From the time Kyrill was conscripted into the Red Army in the summer of 1941 until I found his file in the German archives in 2001, his family had absolutely no idea whatsoever what had become of him or of his fate,” said historian and retired U.S. Army colonel Jerry Morelock, Kyrill’s grandson-in-law.

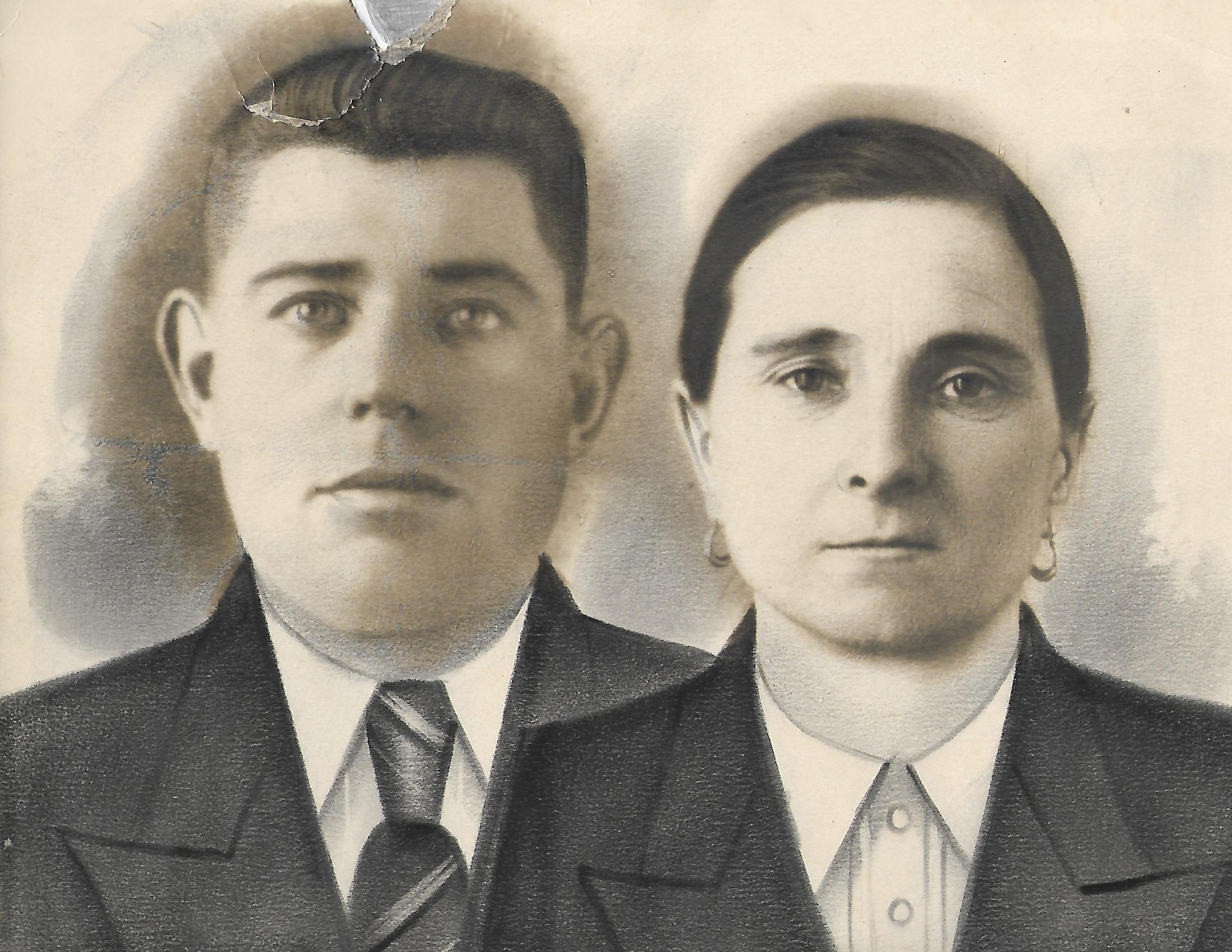

An ethnic Cossack, Kyrill was born in 1910 in the small village of Yefremovka during the reign of Russian Czar Nicholas II. The village, consisting of a few hundred peasants, was established during the reign of Catherine the Great as an outpost to defend the area against incursions by Crimean Tatars. One of five brothers, Kyrill was entitled to inherit his family’s farm, but lost his rights to his inheritance during Lenin’s Bolshevist Revolution. His wife also suffered personal loss due to political upheaval—Varvara Pavlovna Bozkho was left legally widowed after her first husband was denounced as a “kulak” due to his property holdings, arrested by the secret police and deported into exile.

Kyrill and Varvara married in 1935. Their daughter, Galina, was born on May 3, 1936. The couple lived in Kyrill’s hometown of Yefremovka, where he continued to work on his family’s former farmland until 1941 when he was suddenly drafted into the Red Army. Kyrill had no military experience. When he left home, he expressed foreboding to friends and family that he did not expect to return.

Sadly his premonition proved true. Kyrill found himself “thrown into the cauldron of battle in a futile effort to try to stop, or at least slow somewhat, the seemingly irresistible German advance,” according to Morelock. He was captured in August or September 1941, one of 2,300,000 Red Army soldiers taken prisoner by invading German troops. According to Morelock, possible locations for his capture include the Kiev Pocket, Poltava area or the First Battle of Kharkov in October 1941 as a three-pronged German attack zeroed in on Leningrad, Moscow and Kiev.

Like other Soviet POWs, Kyrill was dragged miles from his homeland and shifted through a series of camps across Northern Germany. He spent time imprisoned at Sennelager, near Paderborn. Used as a slave laborer, he was forced to work in the Ruhr mines.

Kyrill had been a prisoner for 18 months when disaster struck at home. In his native village, his wife and daughter found themselves helplessly trapped when the 1st SS Panzer Division “Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler” (LSSAH) descended upon their community for the purpose of extermination. Responsible for the Malmedy and Wormhoudt massacres, the LSSAH became infamous as the “Blowtorch Battalion” due to its atrocities against civilians and POWs on the Eastern Front. Arriving in the village, the invading Waffen-SS immediately set about murdering the inhabitants.

Varvara and her six-year-old daughter Galina would have met the same fate—had it not been for a sympathetic German truck driver in Wehrmacht uniform, who managed to warn them and helped them to hide in the cellar of one of the village cottages.

“They went inside and the German soldier drove his truck over the cellar opening and parked it there, concealing where they were hidden,” said Morelock.

Mother and daughter remained concealed as their friends, neighbors and community were murdered in what would become known as the Yefremovka massacre, during which 250 people were crowded into the village church and burned alive. This atrocity was later accurately depicted in the 1985 Soviet war film, “Come and See,” although the location was different in the film, according to Morelock. A total of 900 men, women and children in the area were shot or burned to death.

Varvara hoped to be reunited with Kyrill, and at one point wished to travel to Kharkov to attempt to obtain his release from the Germans based on rumors she heard. However, she was unable to make the journey, as Kharkov was more than 300 miles away and her daughter Galina was then bedridden with illness. Mourning the loss of her husband—and not knowing that Kyrill had already been transported to labor camps in Germany by then—Varvara struggled with guilt for the rest of her life.

Enduring forced labor, starvation and abuse, Kyrill survived years in captivity. He managed to cling to life until 1944, when he was finally overcome by illness. Because he was a Soviet prisoner, the Germans had denied Kyrill his legal right to correspond with his family. He perished at Dalum concentration camp in Emsland—a holding camp where the Nazis sent ill Russian prisoners. His cause of death was likely typhus. Nobody at home knew his whereabouts—nor did they dare hope to find out.

“Kyrill’s family were, ultimately, at the mercy of the USSR government which made no concerted effort to find out the fates of Red Army soldiers who were captured,” said Morelock. “Of course, they were devastated that their loved one was not coming back, and grieved over him and suffered for his loss as any human beings would do. Yet, unlike Americans who expect their government to account for every service member who went off to war, Soviet citizens merely accepted that their missing loved ones were irretrievably lost and were never coming back, regardless of each one’s individual fate.”

After marrying Kyrill’s granddaughter Inessa, Morelock made use of contacts and knowledge he gained while serving in the U.S. military as he embarked on a mission to find the truth. “My first efforts produced a dead end, but eventually I was able to make contact with officials in Berlin who were able to produce Kyrill’s ‘official’ German POW file,“ he said.

After decades of doubts and darkness, Kyrill’s family finally learned his whereabouts—he was one of the few named Soviet POWs buried at a site north of Dalum. Sadly, his wife Varvara had passed away by that time. However, Kyrill’s surviving relatives were “amazed and thrilled” to learn the truth, according to Morelock—especially Kyrill’s daughter Galina, the resilient child who survived the Yefremovka massacre, who had last seen her father in 1941.

“Galina was, understandably, in tears, and couldn’t stop thanking me—her ‘Golden Son-in-Law’ as she called me!—for finding out what happened to her father,” recalled Morelock. “There was a lot of crying and hugging one another, and it was like a long-lost relative had been ‘found.’”

“As a historian, I think one of the most rewarding things for me personally was successfully solving the historical mystery of what happened to Kyrill Vasilyevich Kasyanov,” said Morelock. “But, for my new family’s perspective, it was so satisfying and rewarding to me to provide a very appreciated and wonderful ‘gift’ to Galina and Inessa and Kyrill’s descendants by telling them exactly what had happened to Kyrill after he marched off to war in the fateful summer of 1941. I am very proud to have been able to tell them what happened to him.”

‘Hidden Holocaust’

Sadly there are many former Red Army POWs lying buried in Germany whose fates remain unknown to their families and whose suffering continues to go largely unrecognized.

“I am convinced that crimes that were committed must be examined at some point in history,” said Preusse, speaking of the importance of the new exhibit. “But politics has also suppressed this topic for a long time, and thus perhaps that is why there is no general awareness of this to this day.”

At Südfriedhof cemetery, citizens of Nuremberg shuffle past on quiet afternoons and place wreaths at family plots. Not far off, in a silent corner of the graveyard, thousands of Soviet soldiers lie in silence beside cold stone monoliths—masses of men, buried in hundreds per each small plot. Names are inscribed on bronze plaques beside these monoliths. Yet no wreaths or family tributes fill this lonely spot—it is likely their relatives, at a loss to find information, still consider them missing.

In Russia today, heroes of World War II continue to be commemorated with victory parades, statues and tales of fights on the frontlines. But the story of these men—who fought so hard for survival in the hope of one day returning home—remains largely untold, and their courage passed over without recognition. The meadow stays quiet. If the POWs are lucky, they might be remembered by a compassionate passerby with a tiny flower or small token.

“The German mistreatment and abuse—really murder, through shooting, starving, exposure and associated diseases—of Red Army POWs in World War II is, essentially, a ‘hidden Holocaust’ of the war,” said Morelock. MH