Accused of drunkenness at Second Bull Run even though evidence showed he suffered multiple epileptic seizures

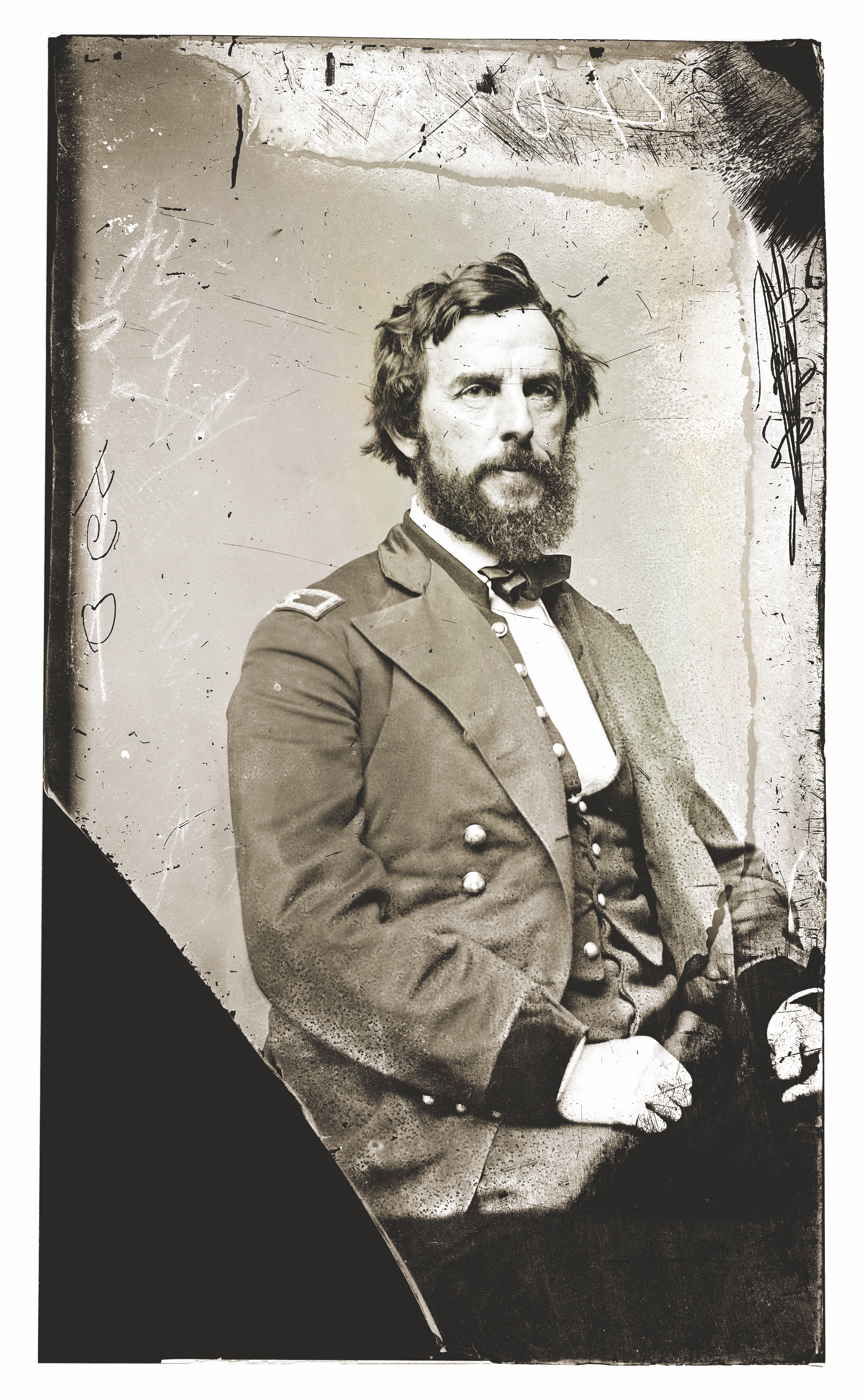

Rufus King’s place as the renowned Iron Brigade’s first commander is, unfortunately, often relegated to mere footnote mention. Rather, the Union brigadier general’s once-proud name and reputation were irrevocably scarred by other Civil War events, specifically several epileptic seizures he suffered while in action and accusations that he made an unauthorized withdrawal from the field after the Battle of Brawner Farm in August 1862 and was then drunk and incapacitated during the subsequent Second Battle of Bull Run. An 1833 graduate of the U.S. Military Academy whose grandfather signed the Constitution in 1787, King had enjoyed success before the war both in the Army and in private life. But he would be haunted by those allegations of wrongdoing for the remainder of his life. Recalled King’s son, Charles— a West Point graduate himself, brigadier general during the Philippine Insurrection of 1899-1902, and later the author of 60 books—his father “for long years…had to bear the stigma, and it ruined his health and broke his heart.” None of King’s antebellum acquaintances, including the likes of Robert E. Lee, William H. Seward, and Thurlow Weed, would have anticipated this fate for this esteemed descendant of a founding father.

Born on January 26, 1814, in New York City, Rufus King shared the name of his famed grandfather. He attended Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School in New York, and entered West Point as a 15-year-old in July 1829, graduating fourth in his class four years later.

Commissioned a brevet second lieutenant in the U.S. Corps of Engineers, King served as an assistant to Captain Robert E. Lee and aided in the construction of Fort Monroe in Hampton Roads, Va. King greatly admired the Virginia officer, even after Lee chose to serve the Confederacy. “Father had a high opinion of General Lee,” Charles King remembered, “regarding him as the peer of any man in either army, whether from the viewpoint of a soldier or a gentleman, but deplored his taking up arms against the union of states.”

King demonstrated that reverence the winter of 1861-62 while stationed in Washington, D.C., near Lee’s estate at Arlington, Va. “My mother, who joined him there,” Charles wrote, “took it upon herself to sort out the more valuable items of clothing and other personal property belonging to the Lees and have them boxed and labeled with a view to restoring them to their at the close of the War.” Charles was not sure whether the personal items were ever returned to the Lees.

By 1836, Rufus King had grown tired of an army officer’s poor pay and the slow course of promotion and decided his talents were better suited for a civilian occupation. He resigned his commission and accepted an appointment as a civilian assistant engineer in the survey of the New York & Erie Rail Road. His recent marriage to Ellen Eliot in Albany might also have been a factor in his decision to resign. Tragically, Ellen died a year later, and in 1843 King married her younger sister, Susan.

King turned his energies to the publishing industry in New York, first with the Albany Daily Advertiser, a leading Whig newspaper, and then with the Albany Evening Journal as an associate editor. Political power broker Thurlow Weed owned the Albany Evening Journal and served as its senior editor. King took up the part-time study of law while working as Weed’s assistant editor. Through Weed, King befriended William H. Seward, governor of New York and later a member of President Abraham Lincoln’s Cabinet. In January 1839, Seward appointed King New York’s adjutant-general.

Soon, King became active in New York’s state militia. He commanded the Albany Burgess Corps, an organization composed of the city’s young businessmen and mechanics, described as “one of the finest and most renowned volunteer militia organizations of that day.” He was placed in command of New York’s militia during the so-called Anti-Rent War of 1839, a revolt by tenant farmers in the upper part of the state. Due to King’s “prompt and energetic measures,” the ringleaders were captured and the revolt suppressed.

In 1845, King relocated to the Wisconsin Territory, settling in Milwaukee and becoming the senior editor and part-owner of the Milwaukee Sentinel and Gazette. (The paper’s name was later changed to the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel.) He became engrossed in civic duties, playing a prominent role in the 1848 constitutional convention that led to the admission of Wisconsin to the Union. He also served as a superintendent of schools in Milwaukee, and gained a reputation in the community for his “charitable and benevolent enterprises”—said to donate often “beyond his pecuniary means” to help his fellow residents.

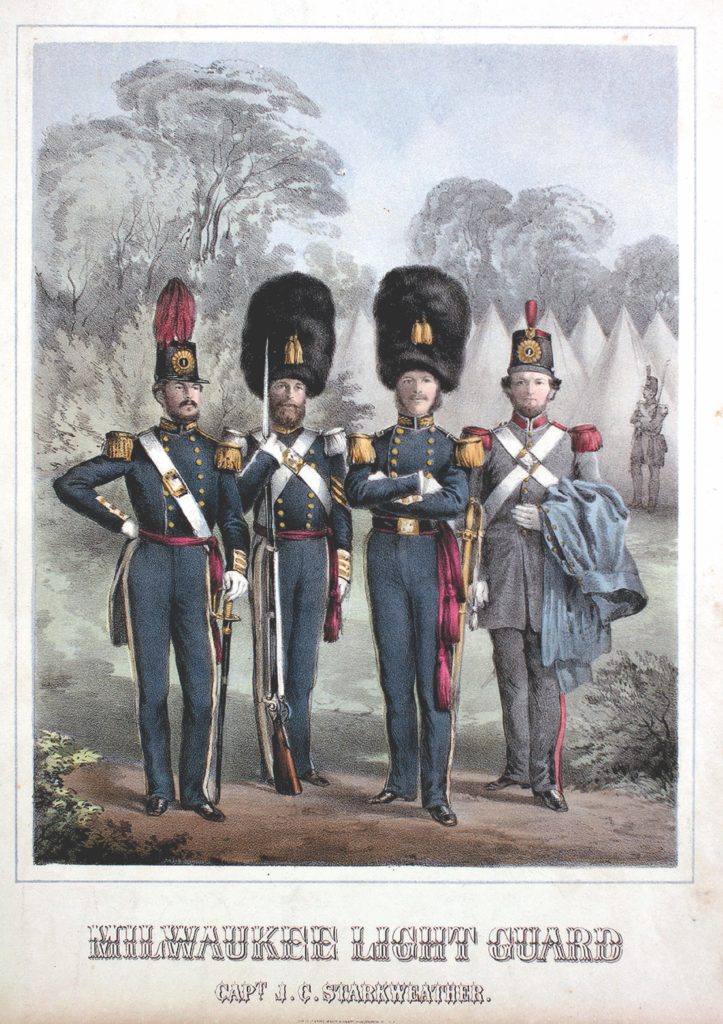

After moving to Milwaukee, King again made the state militia a priority. He was elected captain of the red- and gray-clad Milwaukee Light Guard, serving from 1855 to 1857. Reportedly, King was joyfully received by the company of 60 men, all humbled to have obtained the services of “so competent a military man” and a gentleman who “promised great good to the organization.” They praised him for his “faithful, gentlemanly and courteous manner” while serving as their captain.

King’s longtime association with militias in New York and Wisconsin would serve him well at the start of the Civil War.

Despite his formal military training and extensive experience in arms, King was, in 1846, firmly against the war with Mexico and decided not to volunteer when the conflict opened. His political allegiance was with the Whigs, who, with Henry Clay at their helm, disapproved of the war. Although King spoke out against the war, some of his West Point classmates did venture to Mexico to fight. Three of them—Jacob E. Blake, James W. Anderson, and Erastus A. Capron—were killed there.

In 1861, through the influence of Seward, now President Lincoln’s secretary of state, King was appointed to serve as minister to the Papal States. After traveling to New York, King was preparing to board a steamer destined for Rome when he heard the news of the firing on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor. He had his baggage unpacked and immediately headed back to Washington to enlist. Upon meeting Lincoln, he asked to be commissioned into the Army. The president granted his wish.

On May 17, King was appointed brigadier general of volunteers and returned to Milwaukee to take command of the 5th and 6th Wisconsin Infantry. Those two regiments, plus the 2nd Wisconsin and 19th Indiana, would form the core of what became the Western Brigade and then, more famously, the Iron Brigade. (The 5th Wisconsin was eventually replaced by the 7th Wisconsin, and the 2nd Wisconsin didn’t join King until August 27, 1861, after fighting in Colonel William T. Sherman’s 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, at First Bull Run.) King’s brigade spent the winter of 1861-62 quietly stationed in the defenses of Washington, D.C.

When Maj. Gen. James A. Garfield, the future president, first met King in December 1862, he opined: “He has a weather-beaten, powder-blackened look which reminds us [of] the rugged fighting he has done and the sturdy blows he has struck. Three deep, permanent, vertical wrinkles in the forehead where brow and nose join set off the expression and complete the picture of the man who has evidently got him a large fund of hard sense and hard work.” Behind King’s rough-hewn appearance was a man who came alive in front of an audience. Captain Rufus Dawes of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry recalled King’s elegant speech during the celebration of George Washington’s birthday on February 5, 1862: “Our brigade formed in a semi-circle in close column before the broad portico of the Arlington House, and listened to the reading of Washington’s farewell address, and to an excellent oration from our Brigadier General, Rufus King.”

King’s informal manner and forceful personality endeared him to the brigade’s rough Midwesterners. One account described him as “a plain, common man [who] will listen to the complaint of a private soldier as soon as he will to a colonel.” On March 4, 1862, the appreciative soldiers of the 19th Indiana presented King an elegant jeweled sword made of gold, with “as a token of respect for him as a Soldier & a Gentleman” inscribed on its scabbard.

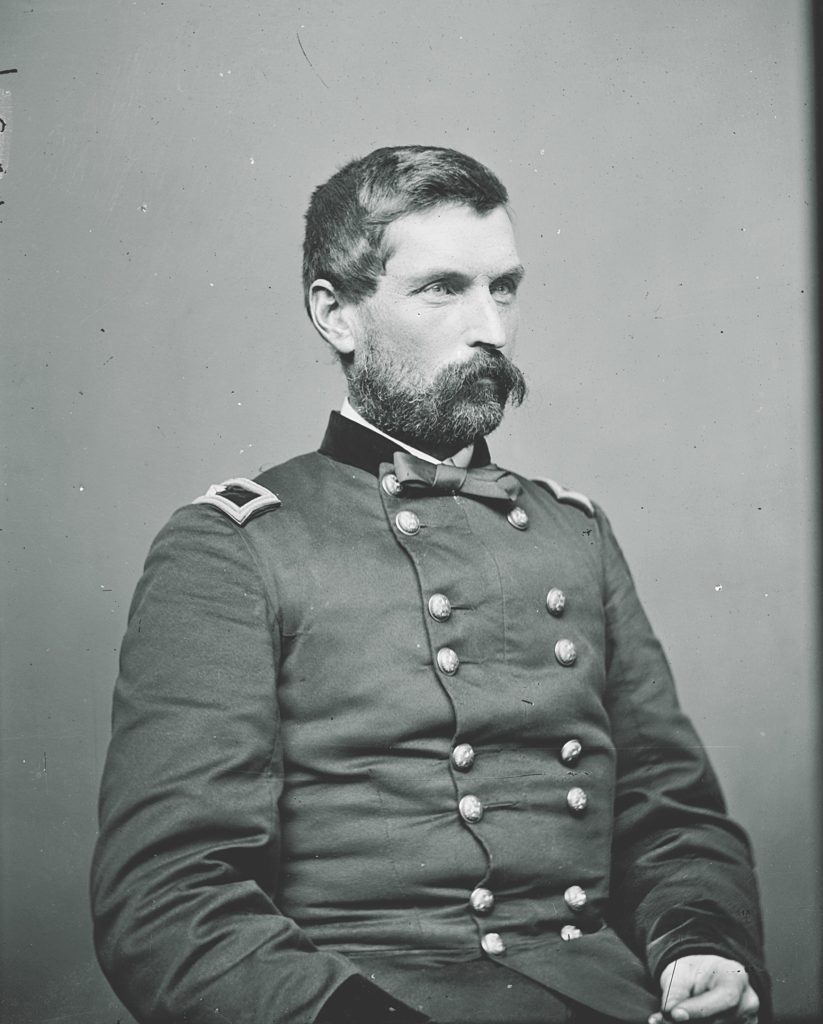

But as King was getting to know his men, he was given command on March 17 of the 3rd Division in the Army of the Potomac’s 1st Corps, under Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell, which became the Department of the Rappahannock on April 4. King named newly promoted Brig. Gen. John Gibbon the brigade’s commander on May 7. Gibbon was the one who required his men to begin wearing the black, tall-crowned Model 1858 Hardee hats in place of forage caps.

King’s promotion came shortly before Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s celebrated invasion of Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. On June 26, Lincoln created the Army of Virginia under Maj. Gen. John Pope, a Western Theater hero who vowed to isolate and then destroy Jackson’s divisions before the arrival of Confederate reinforcements. The Department of the Rappahannock became the 3rd Corps in Pope’s army.

On August 23, 1862, just days before the Federals’ clash with Jackson at Brawner Farm, King suffered an epileptic seizure so severe he was incapacitated and relegated to an ambulance under the care of Peter Pineo, the 1st Division’s chief medical officer. Exhaustion, severe headaches, slurred speech, and abnormal behavior are common after-effects of epileptic seizures. It is undocumented how long King had suffered from this condition, how regularly the seizures occurred, and whether at the time he was being treated for them or how, but King was certainly in no physical condition to command his division after this incident.

Gibbon recalled that on August 26 he could tell King was “still suffering” from its effects. One of McDowell’s aides called King “fatigued out and very weak and sickly,” and, according to Alan Gaff in his book Brave Men’s Tears, King complained about his condition more than once as the division advanced toward Manassas from Warrenton. Despite the horrible timing, King retained command of the 1st Division.

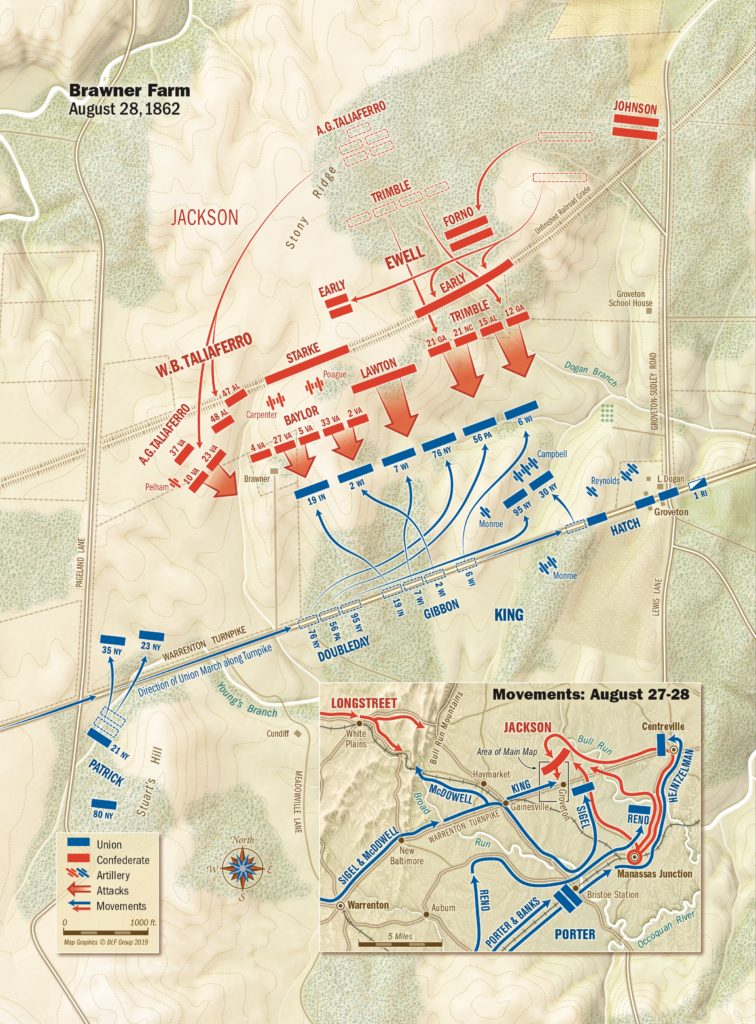

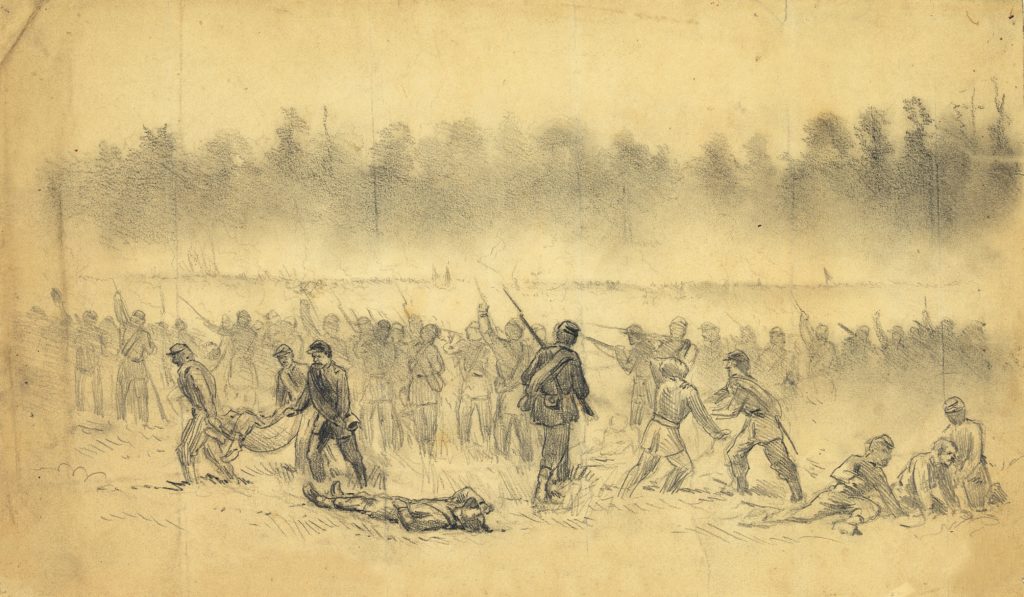

On August 28, five miles from Manassas Junction, Va., the four brigades of King’s division unexpectedly ran into Jackson’s veterans while heading along the Warrenton Turnpike. Leading the advance was the 1st Brigade under Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch, who had first served as a cavalry commander under Pope before being reassigned to the infantry in July 1862. Following Hatch’s men along the pike, in order, were Gibbon’s 4th Brigade, Brig. Gen. Abner Doubleday’s 2nd Brigade, and Brig. Gen. Marsena R. Patrick’s 3rd Brigade. As they marched, Gibbon spotted a battery of Confederate artillery in the distance, indicating that enemy troops were nearby. The Union general had no idea that he was facing the core of Jackson’s army, concealed in the woods and hills of Stony Ridge waiting to spring a trap.

Major General Richard S. Ewell’s and Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro’s divisions attacked Gibbon’s single brigade of 2,100 men. A great deal of the fighting between the blue and gray lines positioned across the Brawner Farm occurred at roughly 70–100 yards. Outnumbered and taking heavy casualties, Gibbon tried to reach out to King located somewhere west of the field. But King apparently was suffering from another seizure. “I looked around and was greatly astonished to see Gen. King prostrate on the ground,” wrote one artilleryman. “I at first thought that he had been struck by a shell, or a bullet, but soon saw that he was in a severe epileptic fit.”

Without its commander for the duration of the battle that evening, the Union defense lacked coordination. Patrick’s green brigade had been thrown into disarray by the fire of a Confederate battery and fell back to the south. Hatch, already beyond the crossroads of Groveton a few miles up the pike, provided Gibbon no support. Doubleday was the only brigade commander to lend a hand, sending two regiments to assist Gibbon’s beleaguered men. Luckily for the Federals, the brigade held steady against the onslaught and maintained its position.

Considered the first day of Second Bull Run rather than a separate engagement in some accounts, the Battle of Brawner Farm (also known as Groveton) ended in a draw, with both sides suffering heavy casualties: 1,200 for the Confederates, including both Ewell and Taliaferro, and 751 for Gibbon—33 percent of his brigade’s strength. But the Federals’ stubbornness and unwillingness to yield to Jackson’s two divisions, which included 800 men of the Stonewall Brigade, quickly helped earn the Westerners the soon-to-be-legendary moniker “Iron Brigade.”

King recovered long enough from his epileptic attack that evening to resume control of his division and assess the tactical situation. He realized that his division was outnumbered (some reports inflated Jackson’s strength to 70,000 men); one of his best brigades had been badly damaged; and no supporting troops were in the vicinity. An hour after the fighting ended, he sent Captain Franklin Haven to give McDowell a message pledging that he would hold his ground against Jackson unless he received contrary orders. The 3rd Corps commander, however, had spent most of the day “lost in the woods” trying to find Pope’s headquarters and could not be found.

Receiving no reply from McDowell, King relied on his own initiative. After 10 p.m., he consulted with his brigade commanders to decide whether to stay or withdraw. Insisted Hatch: “We simply cannot stay. We are utterly without supports. We have got to fall back or be overwhelmed.” Gibbon, who was the most vocal during the conference, later declared that the retreat was “a necessary military measure” and was “the proper one.” The commanders concluded that their current position was untenable and that it would be in their best interest to proceed to Manassas Junction so that they could reunite with the main body of Pope’s army.

In a letter to King dated March 7, 1863, Gibbon offered to shoulder part of the responsibility when King was attacked for ordering the withdrawal. “[H]aving first suggested the movement and urged it on military grounds,” Gibbon wrote, “I am perfectly willing to bear my full share of the responsibility, and you are at liberty to make any use of this communication you may deem proper.”

The division began to pull out in the early hours of August 29. At 9:30 p.m., King sent a letter to Brig. Gen. James B. Ricketts of the 2nd Division, who had been at Thoroughfare Gap but was now falling back through Haymarket and Gainesville: “General: We have been engaged with the enemy, for some hours, but hold our own, and will stay till we hear from you. I think you had better join us here, tho’ that depends, of course, on your orders.” King sent another message to Ricketts about 11:15 p.m., informing him of the council with his generals and his plan to withdraw from the division’s position near Groveton. At some point that night, Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds arrived and conferred with King, promising the support of his Pennsylvania Reserves. King, however, began the march to Manassas Junction.

King had a third seizure when his men reached Manassas Junction. This time, he relinquished command to Hatch, who led the division on August 29-30 during Pope’s embarrassing defeat at Second Bull Run. Major General Fitz John Porter, whose 5th Corps, Army of the Potomac, fought alongside the Army of Virginia at the battle, was among those blamed by Pope for the defeat and was court-martialed in a trial that ran from November 1862 to January 1863. During the trial, Porter claimed that King “was drunk on the 29th and 30th and unable to attend to any duty”—the cause of King’s absence from the battlefield.

What Porter obviously failed to appreciate was that King had suffered from multiple seizures over a period of seven days leading up to the battle. Assuming viable evidence was available that King was showing symptoms of drunkenness (which is doubtful), there is probably a more rational explanation for King appearing intoxicated. Potassium bromide, an iconic salt, was first used to treat epilepsy beginning in the late 1850s and, when digested, it acted as a sedative that caused individuals to appear sluggish and disoriented. Perhaps King had been under the influence of potassium bromide during the battle. Regardless, the general was suffering either from the after-effects of his epileptic attacks or the medication used to treat it, not from alcohol, as Porter was insinuating.

For a man in command of a division made up of thousands of Union soldiers on the eve of a major battle, King’s malady made him unpredictable, maybe even a liability. He should have turned over command to Hatch after he suffered his first seizure on August 23. It is not improbable that he had other episodes before this incident. And if King had a preexisting condition, he should not have been on the front line in the first place. The stress, summer heat, fatigue, and sleep deprivation likely contributed to his seizures. But King was a proud man and, as noted earlier, the grandson of a founding father. He felt it was his duty to remain in the field alongside his men. Besides, his reputation was at stake: What would his fellow Milwaukeeans think if he had left the front on the eve of a major battle? He would have been branded a coward.

In addition to Porter’s contention that he was drunk on duty, King was criticized for disobeying Pope’s orders. After the debacle at Second Manassas, Pope declared in his official report: “I sent orders to McDowell supposing him to be with his command, and also direct to General King, several times during the night and once by his own staff officer, to hold his ground at all hazards, to prevent the retreat of Jackson toward Lee, and that at daylight our whole force from Centreville and Manassas would assail him from the east, and he would be crushed between us.” No order is known to have reached King that night. Pope felt that the unauthorized withdrawal by McDowell from the Groveton vicinity—most notably, by King—allowed Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s divisions to unite with Jackson’s force, culminating in the Federal army’s defeat on August 30.

In addition to Porter’s contention that he was drunk on duty, King was criticized for disobeying Pope’s orders. After the debacle at Second Manassas, Pope declared in his official report: “I sent orders to McDowell supposing him to be with his command, and also direct to General King, several times during the night and once by his own staff officer, to hold his ground at all hazards, to prevent the retreat of Jackson toward Lee, and that at daylight our whole force from Centreville and Manassas would assail him from the east, and he would be crushed between us.” No order is known to have reached King that night. Pope felt that the unauthorized withdrawal by McDowell from the Groveton vicinity—most notably, by King—allowed Maj. Gen. James Longstreet’s divisions to unite with Jackson’s force, culminating in the Federal army’s defeat on August 30.

Despite his damning report, it seems Pope had no ill will toward King. On March 23, 1863, King wrote to Pope challenging his superior’s claim that he hadn’t followed Pope’s “lost order.” In a reply, a much cooler Pope apologized for singling out King. “I am sure you know how highly I esteem your services during that campaign and will readily acquit me of any sort of intention to do you an injustice,” Pope conceded. “I was disappointed, of course, but did not for a moment attach any sort of blame to you. I never knew whether the aide-de-camp reached you that night or not, but I felt always perfectly satisfied that whether he did or not you had done the very best you could have done under the circumstances.”

Writing to his father from Fort Riley, Kan., on April 4, 1876, Charles King recalled meeting Pope for the first time. Charles was understandably sensitive about the subject of his father’s conduct during the campaign, and was surprised by what transpired. “[Pope] talked of you in the most warm hearted way for nearly one hour, and said so many handsome things of the old Division,” Charles explained in the letter. “He was most kind in his inquiries about you…” Charles declared that his father should have pursued an inquiry and “had the matter threshed out,” but Rufus King never did.

Failing in health, and urged by Seward to take over the recently vacated post of minister to the Papal States in Rome, King resigned his brigadier general’s commission in October 1863. He later had a hand in the arrest of an alleged Lincoln assassination conspirator, John Surratt Jr. (the son of Mary Surratt, who was one of four convicted and hanged in July 1865). Surratt had joined the Papal Zouaves under a false identity before being caught.

King continued to act as minister until the mission to the Papal States was closed in 1867. He briefly served as the deputy comptroller of customs for the Port of New York before retiring from public life in 1870. He died from pneumonia on October 13, 1876, at the age of 63.

Charles King persevered in trying to vindicate his father’s reputation, even urging Pope in the early 1880s to “correct the evil done” by his ambiguous Second Bull Run report. Supposedly Pope promised Charles, “I will the first chance I get.” The general, however, died unexpectedly in his sleep while visiting the Soldiers’ and Sailors’ Home in Sandusky, Ohio, in September 1892, taking any chance to exonerate Rufus King’s name with him to his grave.

Frank Jastrzembski, a frequent contributor to America’s Civil War and the blog “Emerging Civil War,” is the author of Admiral Albert Hastings Markham: A Victorian Tale of Triumph, Tragedy and Exploration and Valentine Baker’s Heroic Stand at Tashkessen, 1877. He runs “Shrouded Veterans,” a nonprofit mission to identify and repair the graves of Mexican War and Civil War veterans. [For more information, see https://m.facebook.com/shroudedvetgraves/].