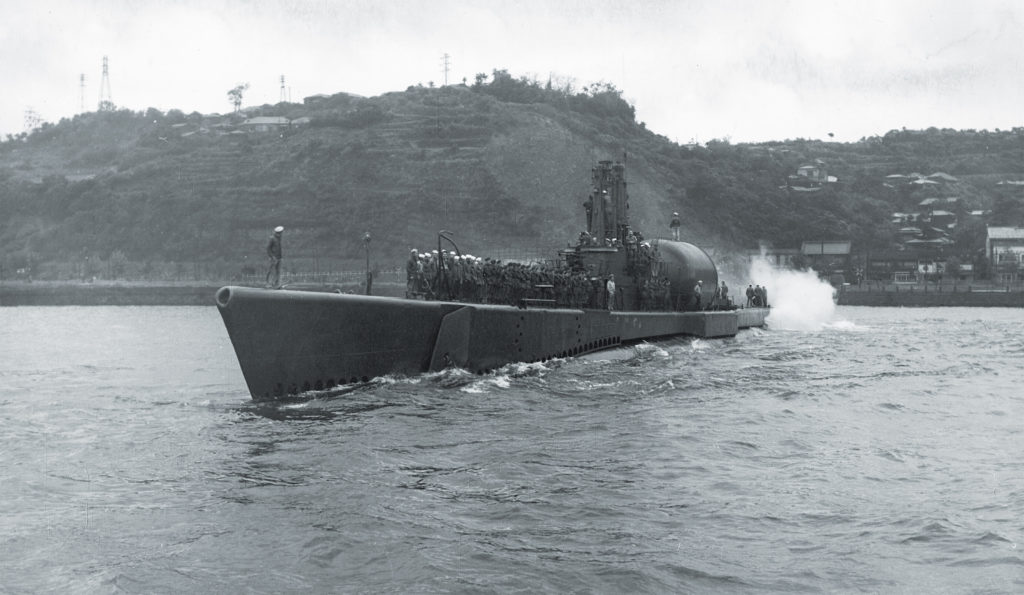

On the evening of Oct. 1, 1950, the submarine USS Perch surfaced 4 miles off the east coast of North Korea. A veteran of World War II combat against Japan, the warship had been converted into a troop transport and in place of torpedo tubes carried troops—67 members of Britain’s 41 (Independent) Commando, Royal Marines. Led by Lt. Col. Douglas B. Drysdale, the men were among the first members of their service to go into action behind enemy lines in the Korean War. Their target that night was a rail line used by the North Koreans to transport supplies and personnel south.

The commandos busied themselves retrieving a 24-foot motorboat, dubbed the “skimmer,” and inflatable rafts from an airtight 36-foot-long cylindrical cargo hangar welded to the submarine’s aft deck—a feature that led the marines to dub the vessel the “Pregnant Perch.” With the boats in the water, the skimmer towed the rafts toward the beach while Perch waited on the surface. Once ashore the raiders planted explosives along the tracks in tunnels and an adjoining culvert, though the latter presented an unexpected challenge. “The plan was to crawl to the center [of the culvert], then pack in as much explosives as possible,” commando Fred Hayhurst recalled. “The culvert, however, housed years and years of rotting, smelly rubbish. The first task was to clear some of the obstacles, then crawl through the slimy mess with packs of explosives.”

Detonated as planned, the explosives destroyed a long section of railway, and the raiders made it back to Perch in the predawn darkness. They returned with the body of Peter R. Jones, the first Royal Marine casualty of the war, who’d been killed during a firefight with North Korean troops. Despite that loss—and others to come—the successful raid marked the beginning of a highly effective covert war carried out by Britain’s famed “green berets.”

Assembling the Team

The Royal Marines’ participation in the Korean War officially began just two months before the rail line attack with the Aug. 16, 1950, formation of 41 (Independent) Commando at Bickleigh Barracks, on the outskirts of Plymouth in southwest England. The unit’s hasty creation stemmed from a request by Vice Adm. C. Turner Joy, commander of U.S. Naval Forces, Far East, for a raiding force to disrupt enemy supply lines on North Korea’s east coast. Amphibious raiding was exactly the type of operation at which the British commandos excelled, and Royal Navy Vice Adm. Sir Patrick Brind offered such a force to the United Nations Command.

The only problem was that 3 Commando Brigade—the Royal Marines’ primary field formation—was already battling communist guerrillas in Malaya. The marines were thus forced to recruit volunteers (though few former members of 41 Commando recall “volunteering”) from three different groups. The first were marines under Drysdale from the commando school at Bickleigh Barracks. The second comprised sailors and marines of the British Pacific Fleet, who became known as the “Fleet Volunteers.” The final volunteers were marines en route to Malaya aboard the troopship Devonshire who were diverted to Japan.

Assembling the Fleet Volunteers and Devonshire men in Japan was easy enough. Deploying those at Bickleigh Barracks was more complicated. The British-based marines ultimately flew to Japan via a chartered civilian flight. So as not to attract attention during fueling stops in neutral countries, they traveled in civilian clothes. Their weak disguise likely fooled few onlookers, however, given that most of the men wore their combat boots.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

All three marine groups eventually gathered in Japan at Camp McGill, a U.S. Army training facility near the sprawling American naval base at Yokosuka. As 41 Commando would be under U.S. naval operational command, the British troops were issued American uniforms, weapons and equipment, though they retained their boots and distinctive green berets. Accents aside, there was little to distinguish them from their American counterparts. After familiarizing themselves with the weapons, the marines underwent rigorous training on raiding techniques. By late September elements of 41 Commando were ready for operations.

The Train Wreckers

The first members of 41 Commando to see action belonged to Poundforce, a 14-man team under the command of Lt. Edgar Pounds. Attached to a U.S. Army Ranger battalion, Poundforce supported the Inchon landings by conducting a diversionary raid along the Korean west coast on the night of September 12/13. Following the raid, Poundforce was attached to the U.S. 1st Marine Division (1st MARDIV), which by month’s end helped liberate Seoul.

Following the October 1/2 raid from Perch, Drysdale’s second-in-command, Maj. Dennis Aldridge, led two separate raids on October 5 and 6 by 125 men of the commandos’ C and D Troops. Put ashore by landing craft from the U.S. high-speed transports Bass and Wantuck, the raiders detonated 4 tons of explosives beneath bridges and culverts and in tunnels along the same key rail line. Another commando was killed, but that operation was also successful. It and further raids on the North Korean rail system led 41 Commando to be widely referred to as the “Train Wreckers.”

As U.N. forces rapidly advanced northward up the Korean Peninsula, opportunities for coastal raiding tapered off, and 41 Commando was put under the command of 1st MARDIV, the latter having transferred east following the liberation of Seoul. Numbering just 235 men, 41 Commando was to serve as a reconnaissance company on the division’s left flank as it advanced north from Yudam-ni.

After enjoying Thanksgiving with their American brothers-in-arms at Hungnam, the men of 41 Commando boarded twenty-two 2½-ton trucks and, accompanied by a weapons carrier and Drysdale’s jeep, traveled north through Funchilin Pass to Koto-ri. On their arrival famed World War II U.S. Marine combat leader Col. Lewis Burwell “Chesty” Puller, commander of the 1st Marine Regiment, informed Drysdale that upward of 120,000 Chinese troops had attacked the U.S. X Corps along a broad front west and south of the Chosin Reservoir, blocking the road to the north.

As part of a plan for the 1st MARDIV to fight its way through to Hagaru-ri, at the southern tip of the reservoir, the Royal Marines formed the nucleus of Task Force Drysdale, which included Company G, 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines; Company B, 3rd Battalion, 31st U.S. Infantry; and 1st MARDIV support elements. The task force—922 men and 141 vehicles under Drysdale’s command—began its advance at 9:30 a.m. November 29, with 41 Commando and Company G leading the way.

Task Force Drysdale had advanced not 2 miles before its lead elements contacted the Chinese. Enemy resistance was heavy, but 17 tanks pushed up the line drove back the Chinese. The task force resumed its advance at 1:50 p.m. and continued until Drysdale called a halt at 4:15 to confer with 1st MARDIV headquarters. Increasingly concerned the Chinese might capture Hagaru-ri, division commander Maj. Gen. Oliver P. Smith ordered Drysdale to press on. As soon as the tanks had refueled, the task force resumed its advance. When Drysdale asked the commander of the armored element to disperse his vehicles throughout the convoy, the latter refused, fearing individual tanks would be easier for the Chinese to pick off. His decision proved disastrous. Halfway to Hagaru-ri the convoy entered a defile and came under ambush by the Chinese, who hit a truck with a mortar round, splitting the column.

“The trucks jerked to a halt,” Royal Marine Dave Brady recalled, “and as they did so, there was some fairly intensive firing from the hills alongside.” Tumbling over the side of his truck, Brady heard someone shout, “Get off the road and up the hill!” He did as told and sought cover. “I rolled onto my side and drew my bayonet and, with trembling fingers, after many attempts attached it to my stupidly small carbine. Alongside me was [an American] soldier. His face was cradled in his hands.…I pushed him, and he rolled onto his side, face toward mine, or rather, what was left of his face.”

The latter half of the split column comprised one of 41 Commando’s heavy weapons sections, the assault engineers, most of Company B and elements of Drysdale’s command group. Strung out along the road in several defensive positions, they managed to hold off Chinese assaults throughout the night. Most of the heavy weapons section, led by Cpl. Ernest Cruse, managed to reach Hagaru-ri the next day, albeit reporting many cases of frostbite. Those from the command group, led by Capt. Patrick Ovens, narrowly avoided capture by withdrawing to Koto-ri. Meanwhile, the lead half of the column pressed on under intense Chinese fire until halted by mortar fire less than a mile from Hagaru-ri. Three Royal Marines were killed and several others, including Drysdale, wounded during that stage of the advance. Rallying, the men fought through into town.

The advance had cost Task Force Drysdale 321 casualties and 75 vehicles. Scarcely 100 members of 41 Commando made it to Hagaru-ri, while 60 fell as casualties. Those in the column managing to reach town were given food and welcome shelter from temperatures that plunged to -24°F. Placed under the command of the U.S. 5th Marines’ Regimental Combat Team (RCT), the surviving Royal Marines were designated as “garrison reserve.” Yet before long they were in action again, launching a counterattack to retake Company G’s left flank on East Hill, a crucial feature in Hagaru-ri’s defenses.

A Freezing Ordeal

Unknown to the defenders of Hagaru-ri, the Chinese had suffered some 5,000 casualties. Such horrific losses didn’t prevent the enemy from pressing their offensive and rolling back U.N. forces. Farther west Eighth Army had been compelled to withdraw, and three U.S. Army battalions east of the Chosin Reservoir had suffered up to 75 percent casualties. The situation for U.N. forces looked bleak.

During a high-level briefing at Hagaru-ri the commander of X Corps authorized 1st MARDIV commander Smith to destroy his heavy equipment before retiring to Hungnam. But Smith said the division would fight its way out and take its equipment with it. The general also made it clear “withdrawal” was not a word in the Marine Corps vocabulary. The coming move would represent an “advance” to the south.

The U.S. 5th and 7th Marine RCTs at Yudam-ni were first withdrawn south to Hagaru-ri, arriving on December 4 in subzero temperatures to a warm welcome by members of 41 Commando. The next day the Royal Marines tried to recover nine 155 mm howitzers that had earlier been abandoned. The attempt failed, though they later destroyed the guns. On the positive side, U.N. aircraft managed to fly in 537 reinforcements to Hagaru-ri and evacuate a number of casualties—including 25 Royal Marines.

Smith’s plan to “advance” south called for the besieged garrison at Hagaru-ri to break through to Koto-ri. The 7th Marine RCT was to lead the way with the 5th RCT and 41 Commando acting as a rear guard. The move would be dangerous, though U.S. and British troops would receive air support from carrier-based U.S. Navy and Marine Corps aircraft. The withdrawal began on December 6, with 10,000 men and 1,000 vehicles setting out under constant threat of Chinese attack. “The whole column moved at a very slow pace,” one Royal Marine recalled. “All except the drivers were walking. This was to prevent the enemy getting close enough to toss grenades at the vehicles. It was also to prevent people freezing to death in the backs of trucks.”

The move toward Hungnam ran into a delay, as the Chinese had destroyed a section of bridge at a hydroelectric plant spillway in Funchilin Pass. U.S. engineers rushed to span the gap using steel trackway parachuted into the pass. With repairs completed, 41 Commando moved out of Koto-ri amid a snowstorm on the evening of December 8, tasked with holding high ground along the road ahead to guard against Chinese attack. The next morning the marines turned back to Koto-ri to relieve 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, in defense of the perimeter. Finally, 41 Commando left Koto-ri with the 5th RCT, marching the 23 miles to Hungnam in awful weather conditions. On arrival Drysdale’s men were loaded onto trucks and taken to a tented assembly area. Their ordeal of the Battle of Chosin Reservoir was over.

On December 11 the remaining elements of 1st MARDIV arrived at Koto-ri. As promised, Smith and his Marines had fought their way out and managed to bring most of their equipment with them. After greeting the battered but unbowed Americans, the men of 41 Commando embarked on transports waiting off the coast at Hungnam, bound first for Pusan and then Masan. All told during the Chosin Reservoir campaign 41 Commando suffered 93 casualties, including most of the assault engineers, signalmen and NCOs of the heavy weapons sections. Thus the unit was withdrawn to Japan. After a period of R&R at Ebisu Camp in suburban Tokyo 41 Commando were sent to HMAS Commonwealth, the Australian naval base at Kure, where they received replacement personnel and equipment. The commando also undertook additional training, for their combat role in Korea was only just beginning.

More Raiding

On April 2, 1951, the reconstituted 41 Commando embarked on the dock landing ship USS Fort Marion and high-speed transport USS Begor to mount another demolition raid. Their target was the coastal rail line near Sorye-dong, North Korea, which the enemy was using to transport men and materiel from Manchuria to Hungnam. The U.S. Navy provided both air and naval gunfire support.

Delayed by thick fog, the raid began just after dawn on April 7. After a two-hour naval bombardment D Troop landed at 8:05 a.m., followed an hour later by the engineers. After blasting out 16 boreholes along a load-bearing railway embankment, the raiders packed each cavity with 80-pound TNT charges. After detonating the initial charges, the team repeated the process, the subsequent explosions opening a gap in the embankment some 100 feet wide and 16 feet deep. Finally, the commandos salted the craters with dozens of anti-personnel mines to hinder North Korean repair efforts. Eight hours after landing the Royal Marines boarded landing craft and returned to the waiting ships. The raid had been a smashing success, and no casualties were incurred, despite a brief firefight between members of C Troop and the enemy.

The next target for 41 Commando was Yo-do, an island in Wonsan Harbor, some 60 miles behind enemy lines. Secured in early July and established as a forward base from which to mount further raids, the island was initially garrisoned by South Korean marines. Through that autumn the commandos established forward bases on the neighboring islands of Mo-do, Tae-do and Hwangto-do, from which several raids were mounted. During one August 30 raid against enemy artillery batteries on Ho-do Pan-do island B Troop lost two marines in a clash with enemy soldiers, and five other members of the commando were captured when their landing craft ran aground on nearby Kalma-gak.

On September 27 Drysdale and B Troop embarked on the high-speed transport Wantuck for a raid on Songjin (present-day Kimchaek), a port city on North Korea’s northeast coast. The intention was to ambush enemy reinforcements in the area. Two parties landed, one tasked with creating a diversion while the second carried out the ambush. Though one of their own was wounded during the raid, the marines managed to place mines on the main road and heard several detonate as they withdrew.

On October 3/4 the commando targeted the railway south of Chongjin, though they withdrew on finding it heavily guarded. Two days later the marines attempted another landing near Sorye-dong, but their canoes came under fire as they reached shore, forcing another withdrawal.

On October 15 Drysdale was appointed the Royal Marine representative at the U.S. Marine Corps Schools in Quantico, Va. Succeeding him as commander of 41 Commando was Lt. Col. Ferris N. Grant. Meanwhile, the raids against North Korean targets continued, with B Troop landing midway between Songjin and Hungnam on December 2. The commandos returned the following evening, landing a half mile farther north, but again were compelled to withdraw.

The Royal Marines intended to keep raiding that winter, hoping to tie down enemy troops that otherwise would be deployed against U.N. forces elsewhere. But by year’s end 41 Commando received an order to withdraw. Before leaving they mounted a final raid, dubbed Operation Swansong, during which D Troop destroyed enemy vessels at Changguok-hang, on the west coast of Ho-do Pan-do. Finally, on December 22/23 they returned by ship to Sasebo, Japan. Those who’d served a year in Korea returned home to England, while those with time remaining in service joined 3 Commando Brigade in Malaya.

In its 18 months of existence 41 Commando had conducted 18 amphibious landings, most targeting enemy rail and road supply routes. Their actions forced the North Koreans and Chinese to divert considerable resources to the coast to guard against attack. During its raiding operations and participation in the Chosin campaign, 41 Commando lost 21 killed and 28 captured, 10 of whom died in captivity, bringing the total number of fatalities to 31. Several unit members received medals from both the British and U.S. governments, and the commando itself received a U.S. Presidential Unit Citation. Perhaps more important are the lasting bonds formed between the Royal Marines and U.S. Marine Corps.

On Feb. 2, 1952, 41 (Independent) Commando, Royal Marines, formally disbanded. Re-formed in 1960, the unit saw action in East Africa, Northern Ireland and other trouble spots until again disbanded in 1981.

British military historian Mark Simner is a regular contributor to several international history magazines. For further reading he recommends Scorched Earth, Black Snow: Britain and Australia in the Korean War, 1950, by Andrew Salmon; Green Berets in Korea: The Story of 41 Independent Commando, Royal Marines, by Fred Hayhurst; and One of the Chosin Few: A Royal Marine Commando’s Fight for Survival Behind Enemy Lines in Korea, by Dave Brady.