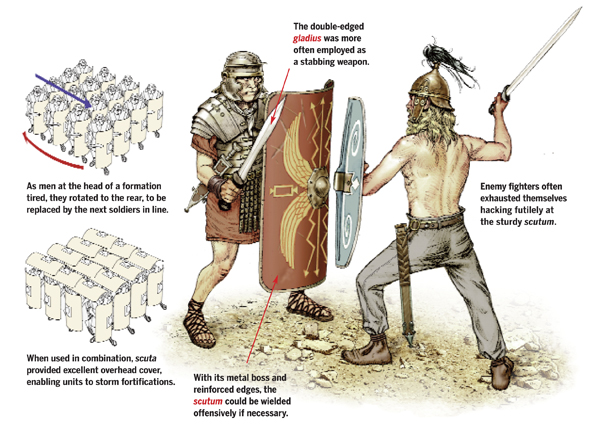

At the height of Rome’s conquests, the Roman foot soldier dominated the battlefield with disciplined coordination of the weapons in his arsenal—first by hurling his thin, iron-tipped pilum (javelin) at the enemy and then deciding the issue at close quarters using gladius (sword) and scutum (shield).

The gladius was a cut-and-thrust weapon, with a double-edged, pointed steel blade about 2 feet long. The scutum, originally elliptical, had assumed a rectangular shape by the early days of the empire. An imperial scutum comprised strips of bentwood, steamed over a form into a convex curve to deflect blows and missiles. The face was covered in hide, its edges bound in rawhide or iron, with a round central boss of bronze, brass or iron. A surviving example found in Syria was 43 inches high and 34 inches wide with a 26-inch gap behind its face.

In close combat, the Roman legionary used his scutum to batter an enemy or deflect blows while seeking an opening to stab his opponent in the torso with gladius or pugio (dagger). Confident in their combined arms, legionaries scoffed at enemy swordsmen who tried to hack their way through a Roman square, waiting until exhaustion rendered their foes ripe for a killing blow. However, scuta offered limited protection from powerful composite bows, such as those used by the Parthians and Huns.

By the early 3rd century, the Romans had replaced the gladius with the 3-foot-long spatha, a design evolution that would lead to the medieval broadsword. And by the late 3rd century, the scutum had reverted to elliptical or circular form. By that time the empire was in decline, and a new era of warfare was in the offing.