In the predawn darkness of Oct. 4, 1759, a detachment of British Maj. Robert Rogers’ Rangers—a mix of provincials and battle-hardened regulars—silently surrounded the sleeping Abenaki Indian village of St. Francis. They had wended their tortuous way north through nearly 100 miles of French-held wilderness and were about to rain fury on its slumbering inhabitants. Three weeks earlier Maj. Gen. Lord Jeffery Amherst, commander in chief of British forces in North America, had defined the mission in deceptively simple terms:

You are this night to set out with the detachment as ordered yesterday, viz. of 200 men…and proceed to Misisquey [sic] Bay, from whence you will march and attack the enemy’s settlements on the south side of the river St. Lawrence in such a manner as you shall judge most effectual to disgrace the enemy.…Remember the barbarities that have been committed by the enemy’s Indian scoundrels.…Take your revenge, but don’t forget that tho’ those villains have dastardly and promiscuously murdered the women and children of all ages, it is my orders that no women or children are killed or hurt.

The mission would enhance the already legendary status of Rogers’ Rangers in the colonies and abroad. It would also cement the unit’s reputation among the French and their Indian allies for unbridled ferocity.

The savagery exhibited by both sides during the 1754–63 French and Indian War reflected a style of fighting hitherto unknown to the British. The niceties of “civilized” warfare had little place in the trackless North American wilderness, occupied by indigenous peoples who had no use for interlopers’ concepts of proper combat.

The French had earlier adapted to their unforgiving surroundings, establishing provincial ranging companies and forming Indian alliances. Ultimately, Amherst saw the value of colonial rangers—homegrown guerrilla fighters among whom quarter was neither sought nor expected. Scalping was practiced by both Indians and Anglos.

New Englander Robert Rogers’ company was the most widely known of the British ranging units, and the one most feared by the enemy. A natural leader, Rogers was Amherst’s go-to field officer for both scouting and punitive missions.

By September 1759 Amherst’s forces were stalled at the southern end of Lake Champlain, in the recently built fort at Crown Point. There he sat, building ships and awaiting word of Maj. Gen. James Wolfe’s progress in capturing the French stronghold of Quebec City before moving his army north. Communication between the generals was practically impossible, given the more than 200 miles of enemy-held wilderness that lay between the two armies.

On August 8 Amherst sent young Capt. Quinton Kennedy on a dual mission: to deliver dispatches to Quebec City and return with Wolfe’s response; and to persuade the Abenakis, one of France’s most effective and feared tribal allies, to sign a peace treaty with Britain. Things did not go as planned, however, as the Abenakis took the captain and his party captive.

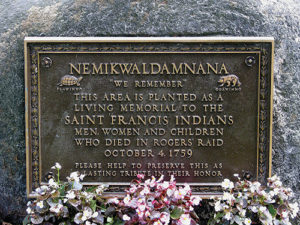

By that point both the British and the colonials had had more than enough of the Abenakis. Since the late 1600s their warriors had sallied forth from their Quebec village of St. Francis—known to the French as Saint-François-du-Lac and to the villagers themselves as Odanak (“coming home”)—and raided New England’s Anglo settlements with devastating effect, killing or capturing hundreds. The Abenakis had recently played a significant role in destroying Fort William Henry, during which they’d emptied the graves of several soldiers. “My brother Capt. Richard Rogers died with the smallpox a few days before this fort was besieged,” Rogers noted in his journal, “but such was the cruelty and rage of the enemy after their conquest that they dug him out of his grave and scalped him.”

The ranger leader thus had a personal as well as a professional score to settle with the Abenakis.

Amherst was furious on learning of Kennedy’s capture. Rogers exploited his commander’s dark mood to press his long-anticipated plan for the destruction of St. Francis. Amherst had his own agenda. Sending Rogers deep into hostile territory on a punitive expedition would strike fear into the hearts of the enemy and divert French attention from the activities of Brig. Gen. Thomas Gage, whom Amherst expected to attack Montreal.

The village lay deep in the heart of enemy territory. Simply getting there and back was a daunting proposition. Rogers would have to be highly selective in his choice of manpower.

He assembled the toughest men available. Not all were Rangers; attrition from battle losses and desertion had taken a steep toll. Rogers amended the roster with provincial soldiers and seasoned British regulars. He also enlisted some 25 members of the Stockbridge tribe, Mohicans from western Massachusetts.

Rogers conducted a rigid inspection to ensure each individual had sufficient rations and, as autumn was approaching, warm clothing. He allotted each man two pairs of moccasins and a pair of leggings. Then the major checked their weapons. Each ranger was equipped with a flintlock musket, a powder horn, 60 rounds of ammunition and a hatchet. Many also carried hunting knives and bayonets.

Amherst handed Rogers his orders on September 13, just two days after having received word of Kennedy’s capture. They kept the objective to themselves. Bitter experience had shown that deserters often carried sensitive intelligence to the enemy. Amherst also spread misinformation. “It was put into public orders that I was to march a different way,” Rogers recalled, “at the same time I had private instructions to proceed directly to St. Francis.”

That very night Rogers and some 200 men boarded 17 whaleboats and rowed north on Lake Champlain in the darkness. Rogers had earlier composed a manual he titled 28 Rules of Ranging, and Rule 24 specified that in just such a nocturnal operation each vessel should remain in strict visual contact with the ones before and behind it.

Getting separated was least among Rogers’ challenges. A French fleet patrolled the lake, each ship capable of demolishing his vulnerable whaleboat flotilla. They first had to negotiate a series of narrows. To ensure they weren’t spotted, Rogers beached his vessels to await nights of fog or total darkness.

Almost immediately the company suffered a string of disasters. First, a keg of black powder exploded, badly injuring several men. Then a number of the party fell ill, including more than half of the Indian contingent, likely due to an epidemic that had recently swept Crown Point. Rogers tasked a contingent of their healthier comrades with escorting the injured and sick back to the fort. Only days into his mission he had lost 41 men, including one of his captains.

Continuing to row at night and hide by day, the rangers managed to thread the narrows undetected. “We happily escaped their snares,” Rogers wrote. No sooner had they reached the main body of the lake, however, when fierce autumn storms struck, roiling the waters and soaking the unprotected party. Days ashore were little better. Telltale fires were forbidden, affording the company no opportunity to warm or dry themselves. Finally, in a drenching rain 10 days after setting out, the men beached their boats at Missisquoi Bay. Rogers ordered the vessels and a month’s cache of provisions hidden in the brush, to await their return.

Leaving two Stockbridge warriors to guard the cache, Rogers’ company then struck north afoot. They faced a perilous journey. Unknown to Amherst, Wolfe had captured Quebec on September 13—the very day the rangers had set out from Crown Point. But the bulk of the French army had escaped, moving south to prepare for Amherst’s inevitable advance. Thus the woods and shore around Lake Champlain teemed with French patrols seeking signs of a British incursion. They soon discovered Rogers’ whaleboats, destroying most and hauling away the rest.

Informed that a large British raiding party was in the vicinity, French Gen. François-Charles de Bourlamaque reasoned it was moving toward either St. Francis or the neighboring village of Yamaska. He dispatched 300 partisans and Indians after the interlopers and stationed another 400 near the lakeside cache. They were not yet aware the quarry was their longtime nemesis Rogers.

To evade French patrols, Rogers led his men on a circuitous route, which added considerable distance to their trek and took them through miles of foot-deep, mosquito-infested spruce bog. Progress was painfully slow. At night they cut saplings and laid them branch to branch to provide sleeping palettes above the water. Within days the two Indian scouts Rogers had left at the lake caught up to the party with the news their boats had been discovered and half of the French detachment was on their trail. “This unlucky circumstance (it may well be supposed) put us into some consternation,” Rogers wrote with understatement in his journal.

The major considered his options. Their boats gone, a waterborne retreat down Lake Champlain was out. Well behind enemy lines without hope of support, the rangers would stand little chance fighting their French pursuers. After conferring with his officers, Rogers resolved to push on, fulfill his mission and then withdraw as best he could to a stockaded garrison on the Connecticut River known simply as Fort No. 4. He ordered an officer and six men to return to Crown Point, update Amherst and request provisions be left for them in a glen at the mouth of the Wells River, some 70 miles up the Connecticut from the stockade.

The messengers made it to Crown Point without incident, whereupon Amherst sent a dispatch to No. 4, ordering men and supplies upriver to the rendezvous point. Meanwhile, Rogers’ party pushed farther into enemy territory.

Their boats gone, a waterborne retreat down Lake Champlain was out. Well behind enemy lines without hope of support, the rangers would stand little chance fighting their French and Indian pursuers

Rogers’ route through the spruce bog had discouraged pursuit, thus throwing the French off the scent. Further, Bourlamaque wrongly guessed the raiders were targeting Yamaska, 10 miles southwest of St. Francis, and sent pursuers there. After slogging through the mire for nine miserable days, Rogers’ party emerged on dry land along the St. Francis River. Finally, on the evening of October 3, 22 days after having left Crown Point, the rangers caught sight of the Indian village. By then illness, exposure and exhaustion had whittled down the party to 142 men.

St. Francis comprised a dozen or so board-and-timber houses centered around a church (French missionaries had converted the Abenakis to Catholicism). Granaries and barns dotted the outskirts. It sat atop a 60-foot bluff along the river, with well-worn paths leading down to put-in points for canoes. On reconnoitering, Rogers’ Stockbridge scouts discovered the villagers were holding a dance. According to Abenaki oral tradition, one of the scouts surreptitiously entered St. Francis to warn residents of the present danger. While some heeded the warning and hid in the woods, others remained in the village, refusing to believe any British force could have penetrated so far north into their territory.

Some chroniclers claim all the Abenaki warriors were out pursuing Rogers’ raiding party. Others insist that no able-bodied man, knowing a force of British raiders was in the vicinity, would have left his home and family unprotected. It is logical to assume at least some warriors remained in the village.

Rogers divided his men into three groups, covering the right, left and center of the village. Men were assigned to each house, with Rogers’ best marksmen positioned to shoot any would-be escapees. According to one of the British regulars, “We were to fire the town at once and kill everyone without mercy.”

“At half an hour before sunrise,” Rogers recorded, “I surprised the town when they were all fast asleep.” At the report of a rifle the slaughter began. Rogers’ men shot or tomahawked residents still in their beds or struggling to rise. Tribal tradition has it some villagers held out in the large council house that had hosted the previous night’s dance; if so, they were quickly subdued. Several Abenakis ran down the path toward the canoes. “About 40 of my people pursued them,” Rogers recorded, “who destroyed such as attempted to make their escape that way and sunk both them and their boats.”

The attack ended soon after it began, the surprise complete. Of Rogers’ party, one Stockbridge scout had been killed, Capt. Amos Ogden was badly wounded, and six others were slightly injured. The Rangers captured 20 Abenaki women and children. Retaining as hostages the chief’s wife, two boys and three girls, Rogers let the rest go free. He also liberated five captives—three rangers, a German girl and a provincial soldier.

The raiders then turned their attention to the village itself. They first desecrated the church, destroying tapestries, looting silver candlesticks and reliquaries, and making off with the bell. Rogers then ordered the village put to the torch. “The fire consumed many of the Indians who had concealed themselves in the cellars and lofts of their houses,” Rogers noted. “We found in the town hanging on poles over their doors, etc., about 600 scalps, mostly English.” He failed to mention the scalps his own frenzied men had harvested from the recently slain. For the return march the rangers stuffed their pockets and packs with dried corn, the only available provision.

His victory complete, Rogers realized he must withdraw as swiftly as possible. There would be no mercy once the attack was discovered.

Informed by a captive that some 300 French and Abenakis were only 4 miles downriver, Rogers immediately set out for Fort No. 4, his prisoners and freed captives in tow. As grueling as the northbound trek had been, it paled in comparison to the hardships and horrors that awaited Rogers and his men.

The rangers were more than 200 uncharted miles from No. 4, the weather was growing increasingly colder and stormy, and the forest proved nearly devoid of game. Eight days into the march, to facilitate hunting and foraging, Rogers split his force into small parties. He directed each to rendezvous as planned at the mouth of the Wells River. French partisans and vengeful Abenakis overtook two such parties. According to a French officer, the pursuers “massacred some 40 and carried off 10 prisoners to their village, where one of them fell a victim to the fury of the women.” By then the enemy realized it was the notorious Rogers they were pursuing.

Three weeks into the return march Lt. George Campbell’s party discovered the scalped and mutilated remains of several former comrades, on which “they fell like cannibals and devoured part of them raw, their impatience being too great to wait for the kindling of a fire”

For the survivors starvation was an immediate concern. The corn soon gave out, reducing the men to eating their belts, moccasins, bullet pouches, candle stubs, broiled powder horns and flesh from the scalps they had taken. A contemporary historian interviewed the survivors of Lt. George Campbell’s party, the more desperate of whom “attempted to eat their own excrements.” That wasn’t the worst of it. Three weeks into the march, the historian wrote, Campbell’s party discovered the scalped and mutilated remains of several former comrades, on which “they fell like cannibals and devoured part of them raw, their impatience being too great to wait for the kindling of a fire.” Having sated themselves, they carried off the remains, one Ranger stuffing three partially eaten heads into his pack. According to Campbell, the Stockbridge scouts killed the Abenaki chief’s captive wife and doled out her flesh, though Rogers claimed in an after-action report to have delivered his prisoners safely to No. 4.

Through it all, Rogers maintained order and kept his men moving. The survivors finally arrived at the rendezvous, only to find that the officer in charge of the rescue party had turned back for No. 4 just hours before the rangers’ arrival, taking the supplies with him. “Our distress,” Rogers succinctly wrote, “was truly inexpressible.”

The major directed his men to sustain themselves on acorns, lily roots and whatever small game they could kill. Meanwhile, he fashioned a raft of dry pine trunks and, using hewn saplings as paddles, embarked downriver with two rangers and a captive Indian boy. He vowed to return as soon as possible. Two days downriver a set of falls forced Rogers and crew to abandon their raft and march past the cascade. Lacking the strength to fell trees, they burned down several to lash together another raft. On October 31, at the end of their strength, they staggered into No. 4. Forty-eight days had passed since the rangers had marched out of Crown Point.

Rogers immediately dispatched a canoe laden with supplies upriver to his men. After resting two days, he accompanied a follow-on party of supply canoes. Over the next several days exhausted survivors straggled in to the fort, singly and in small clusters.

At least 49 rangers had perished in the southward flight, succumbing to starvation, exposure and nightmarish enemy retribution. But Rogers had completed his mission—St. Francis lay in smoldering ruins.

How effective was the St. Francis Raid? Chroniclers are divided regarding the butcher’s bill. While Rogers reported having slain “at least 200 Indians,” Burt G. Loescher, in his multivolume work on Rogers’ Rangers, estimates the number to be between 65 and 140. Contemporary French accounts claim a total closer to 30. (A Jesuit priest who visited the village in the aftermath found the bodies of 10 men and 22 women and children amid the smoldering ruins.)

Casualty numbers aside, it was the long-term effects of the raid that most interested Lord Jeffery Amherst, and in this he would be well satisfied. For the first time in recorded history Abenaki territory had been breached and their very homes and families destroyed by an enemy who had no hesitation in using the Indians’ own methods of fighting. The marauding days of the French-allied tribe were over. “From the time of the raid on,” concludes Rogers historian Timothy J. Todish, “the Abenakis ceased to be a threat to the New England frontier.” MH

Ron Soodalter is a frequent contributor to Military History and the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader. For further reading he recommends White Devil: A True Story of War, Savagery, and Vengeance in Colonial America, by Stephen Brumwell; War on the Run: The Epic Story of Robert Rogers and the Conquest of America’s First Frontier, by John F. Ross; and The Annotated and Illustrated Journals of Maj. Robert Rogers, edited by Timothy J. Todish.