Offstage, Elvis Presley was the opposite of the type conventionally associated with the music of which he is universally considered the supreme exponent. He was not remotely rebellious, delinquent, or “animalistic” (a term used in denunciations of his performance style). He was shy and deferential and devoted to his parents. “Nice” is a word often used to describe him.

Presley had had no intention of becoming a rock ’n’ roll singer and he never really considered himself one. He sang rock ’n’ roll songs, but he sang all kinds of songs. He understood that pop music was a business in which a lot of money could be made; if rock ’n’ roll could make him more, he was happy to sing rock ’n’ roll. “I have to do what I can do best,” as he said. But he didn’t sing only for the money. He sang because he was a singer, and his enormous popularity exposed people to genres of popular music they otherwise might not have paid attention to.

Presley was born in East Tupelo, Mississippi, in 1935. His father, Vernon, was a laborer who moved from job to job. The Presleys lived for a time in a Black neighborhood in Tupelo (though in a “White” house). They did not consider themselves, and there is no evidence that they were, racially intolerant. Elvis was an only child—a twin brother was stillborn—and he was especially close to his mother, Gladys. Gladys was dynamic; people liked her. But the family was somewhat insular. In school, Elvis was a bit of an outsider and sometimes got picked on. He stood out not because of any special talent, but because, as a teenager, he dressed up: bolero jackets, a scarf worn as an ascot, dress pants with stripes down the sides. His demeanor remained reserved and respectful. In 1948, the family moved to Memphis, where Presley attended Humes High. (Schools were segregated by law in Tennessee.) The summer after he graduated, in 1953, he walked into the Memphis Recording Service to cut a record.

The Memphis Recording Service was more than a recording facility. Its founder, Sam Phillips, had a vision. Like Presley, Phillips came to Memphis from the deeper South. He was born in 1923 in a small town in Alabama called Lovelace Community, near Florence. His father was a flagman on a railroad bridge over the Tennessee River. Phillips got his start in radio, working in Decatur and Nashville and finally, in 1945, making it to Memphis—in his mind what Paris was for Gertrude Stein and Ernest Hemingway. In 1950, he opened the Memphis Recording Service in a tiny space on Union Avenue a block away from Beale Street, the heart of the Memphis music scene.

“We record anything—anywhere—anytime” was the studio’s slogan. This meant a lot of church services, weddings, and funerals. But Phillips’s dream, the reason he set the studio up, was to have a place any aspiring musician could walk into and try out, no questions asked. Phillips would listen and offer suggestions and encouragement. If he liked what he heard, he would record it. For a fee, the performer could cut his or her own record.

Phillips was patient with the musicians; he was adept with the technology; he was supportive. He thought that music is about self-expression. He liked blues songs especially, but he liked any song that sounded different. The pop sound in 1950 was smooth and harmonic; Phillips preferred imperfection. It made the music seem spontaneous and authentic, qualities that would become key attributes of rock ’n’ roll. Word got around, and musicians no one else would record, many of them Black, turned up at the Memphis Recording Service. Phillips was the first to record Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner, and B.B. King. A musical genre boils down to a certain kind of sound, which is why songs can be covered in different genres. As much as anyone, Phillips helped create the sound of rock ’n’ roll.

To have his recordings pressed and distributed, Phillips relied on independent labels such as Modern Records and Chess. But he found the men who ran those outfits untrustworthy—he felt that they tried to poach his artists or cheated him on royalties—and so in 1952, he started up his own label, Sun Records. That was relatively late in the history of independent labels.

Presley came in to make a record for his mother. At least, that’s the legend; according to a friend, the Presleys did not own a phonograph. He paid $3.99 plus tax to record two songs, “My Happiness,” which had been a hit for several artists, including Ella Fitzgerald, and “That’s When Your Heartaches Begin,” an Ink Spots song. Whether Phillips was in the booth that day or not later became a matter of dispute (he insisted that he was), but someone wrote next to Presley’s name, “Good ballad singer. Hold.” A year later, Phillips invited Presley back to try out a ballad he’d come across. The song didn’t seem to work, and, per his standard operating procedure, Phillips had Presley run through all the material he knew, any song he could remember. After three hours, they gave up. Phillips decided to pursue the experiment, though, and he put Presley together with a couple of country musicians, Scotty Moore, an electric guitarist, and Bill Black, who played stand-up bass, and invited them to come into the studio, which, on July 5, 1954, they did.

They began the session with a Bing Crosby song, “Harbor Lights,” then tried a ballad, then a country song. They did multiple takes; nothing seemed to click. Everyone was ready to quit for the night when, as Elvis told the story later, “this song popped into my mind that I had heard years ago and I started kidding around.” The song was “That’s All Right, Mama,” an R&B number written and recorded by Arthur (Big Boy) Crudup. “Elvis just started singing this song, jumping around and acting the fool, and then Bill picked up his bass, and he started acting the fool, too, and I started playing with them,” Moore said. Phillips stuck his head out of the booth and told them to start again from the beginning. After multiple takes, they had a record. Phillips was friendly with a White disk jockey, Dewey Phillips (not related), who played some R&B on his show on WHBQ in Memphis. Sam gave the acetate to Dewey and Dewey played it repeatedly on his broadcast. It was an overnight sensation.

To have a record that people could buy, they needed a B-side. So Presley, Moore, and Black recorded an up-tempo cover of a bluegrass song, “Blue Moon of Kentucky,” and in July 1954, Elvis Presley’s first single came on the market. In his promotional campaign, Phillips emphasized the record’s appeal to all listeners, pop, country, and rhythm and blues. “Operators have placed [“That’s All Right”] on nearly all locations (White and Colored) and are reporting plays seldom encountered on a record in recent years,” he wrote in the press release. “According to local sales analysis, the apparent reason for its tremendous sales is because of its appeal to all classes of record buyers.” [author’s emphasis]

The trade press picked this up, for, three months after a Billboard article about R&B and White teenagers, it was exactly what the industry was primed to hear. “Presley is the potent new chanter who can sock a tune for either the country or the r. & b. markets,” Billboard noted. “…A strong new talent.”

(Crudup never got a dime from Presley or Sun, but as it happened, Crudup had borrowed much of the lyrics and music for “That’s All Right, Mama” from a Big Joe Turner boogie-woogie number called “That’s All Right, Baby,” recorded in 1939 with Pete Johnson on piano.)

Phillips was reported to have said, “If I could find a White man who had the Negro sound and the Negro feel, I could make a billion dollars.” He denied it. But it is clear that if he was looking for such a person, he would not have picked Elvis Presley to be the one. Phillips called Presley in as a ballad singer, and that is what Presley believed he essentially was. Presley’s favorite among his own songs was “It’s Now or Never,” which is neither bluesy nor rock ’n’ roll, but Neapolitan. Musically, “It’s Now or Never” is a cover of “O Sole Mio.”

“That’s All Right, Mama” started as a joke. Moore and Black thought it was a joke, too. It worked, but it was completely unpremeditated. Presley later admitted that he had never sung like that before in his life.

It is interesting, though, that he remembered the song and that Moore and Black knew how to play it. They just never assumed it was a song that White artists performed. Rock ’n’ roll was not “manufactured” by Phillips, Moore, Black, and Presley in Memphis any more (or any less) than the drip paintings were “manufactured” by the artists Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner and art critic Clement Greenberg on Long Island. They tried something out, and then they tried to figure out why it worked.

“That’s All Right, Mama” was only a regional hit, and not even No. 1 in Memphis. “Blue Moon of Kentucky” was equally popular. Presley didn’t make it onto the national charts for another year; by then, many White performers had stopped refurbishing R&B songs in a pop style and had started imitating them. In 1954, WDIA became a 50,000-watt station reaching the entire mid-South, and by 1955, more than six hundred stations in 39 states were programming for Black listeners—which suggested that not only Black people were listening. Producers could see where the sound was headed.

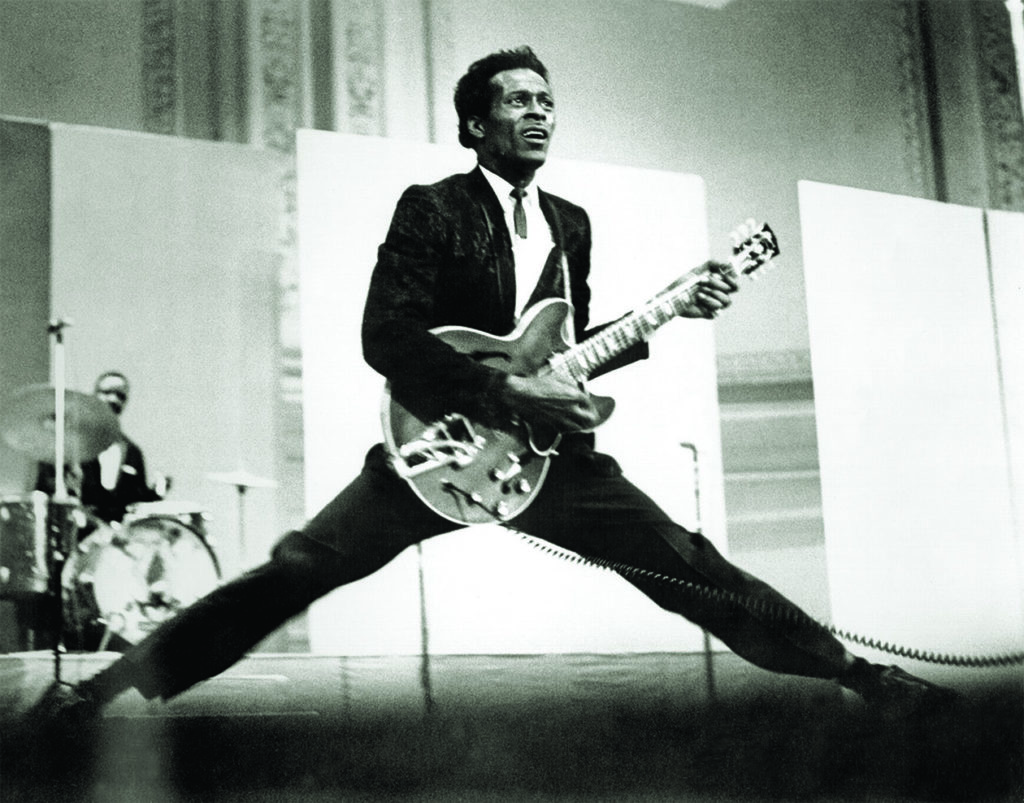

So when, for example, Pat Boone walked into Dot Records, in Gallatin, Tennessee, in the summer of 1955—before Presley had had a national hit—he was shocked to be asked to sing a rhythm and blues song. Like Presley, Boone saw himself as a ballad singer. But he recorded Fats Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” and it went to No. 1 on the pop chart. The same summer, Bill Haley’s “Rock Around the Clock” went to No. 1 after it was heard in the movie Blackboard Jungle. Black performers began to benefit from the popularity of the new sound, too. In May 1955, Chuck Berry recorded “Maybellene” for Chess Records; Chess rushed the record to top New York disc jockey Alan Freed, and it went to No. 1 on the R&B chart and No. 5 on the pop chart. Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” was released a few months later. By January, it had reached No. 17 on the pop chart. Boone and Presley both covered it. Boone’s went to No. 12, Presley’s to No. 20 as the B-side to “Blue Suede Shoes.”

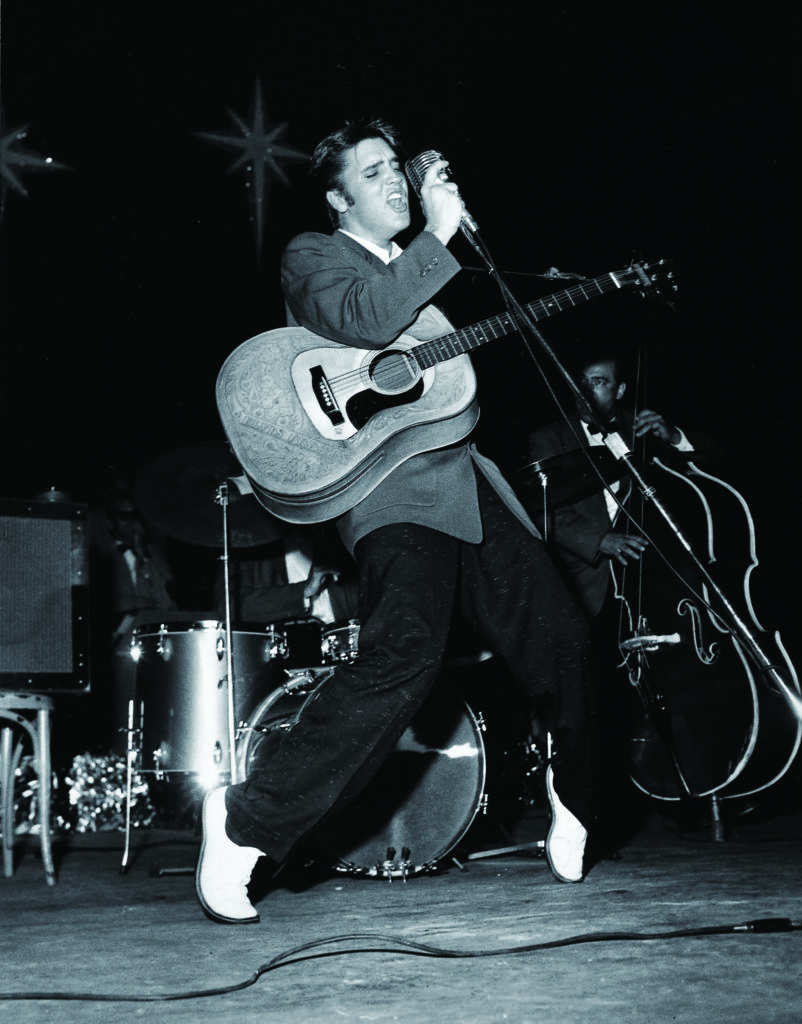

Presley was therefore just one of a number of singers, Black and White, trying to meet the demand for songs with an R&B sound. And among those artists, Presley was originally identified not with rock ’n’ roll, but with country, or “rockabilly,” music. The first article about him in a national publication—in Life in April 1956—referred to him as a hillbilly singer. What transformed him into a breakthrough figure in the evolution of pop music?

A big part of the answer is television. In 1948, 2 percent of American households had television sets. In 1952, it was about a third. But by 1955, 65 percent of households had television sets, and 86 percent had them by 1959. Primetime in those years was dominated by variety shows, hosted by people like Ed Sullivan, Steve Allen, Milton Berle, and Perry Como, that booked musical acts. Since most viewers received only three or four channels, the audience for each show was often enormous, in the tens of millions. Television exposure became the best way to sell a record.

On television, the performer’s race is apparent. Many sponsors avoided mixed-race television shows, since they were advertising on national networks and did not want to alienate White viewers in certain regions of the country. This was true to some extent for advertisers on broadcast radio as well, but there were hundreds more stations. Listeners need not feel trapped. In the first years after it went national, American Bandstand did not book any Black acts. There were few local television stations, and they did little programming. Television desegmented the media audience all over again. Radio had opened the door to music for different audiences; television closed it.

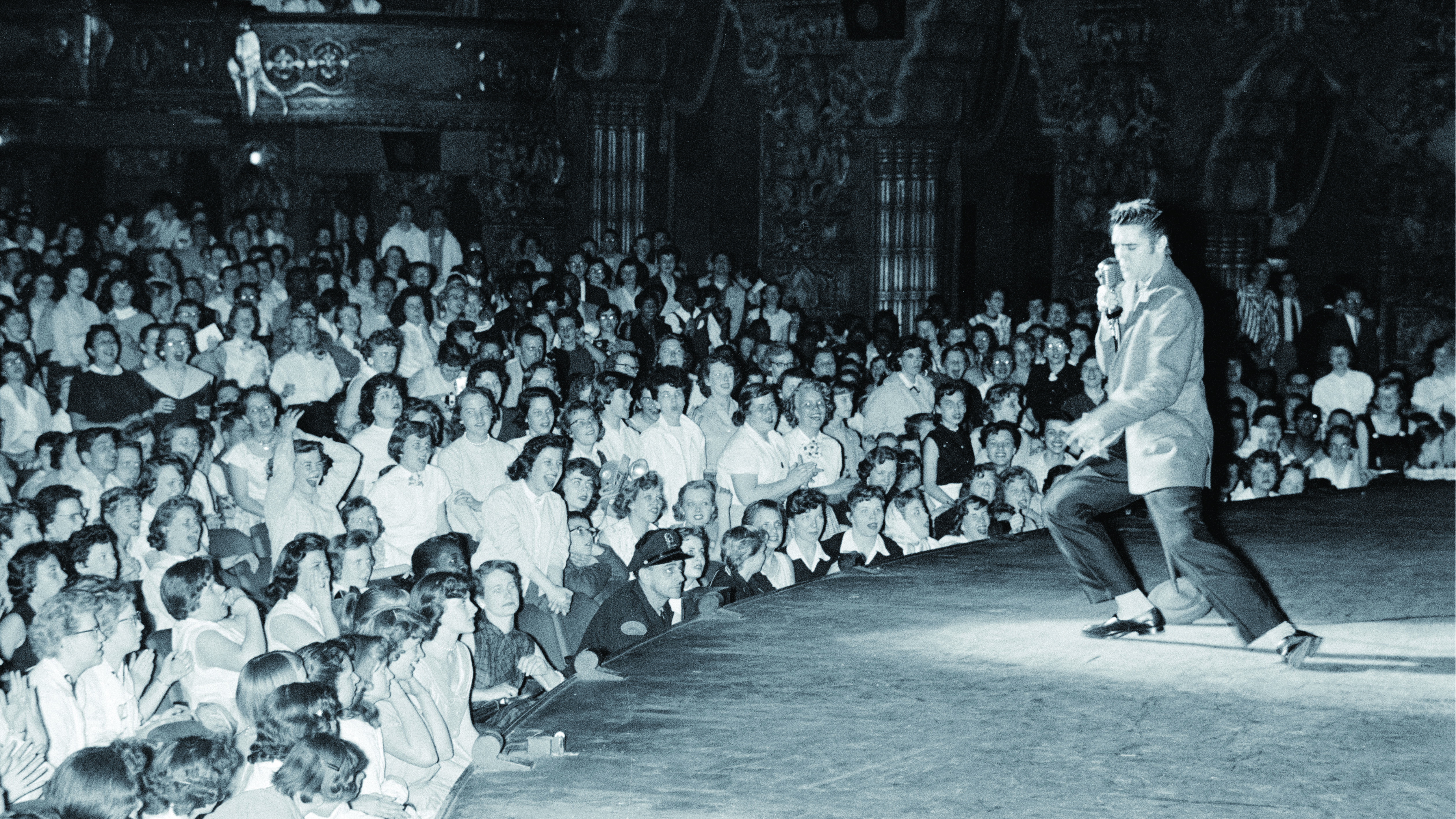

Presley was made for television, and not only because of his race. With a microphone and in front of an audience, he was transformed from a shy young man who tended to mumble into a gyrating fireball with an unbelievably sexy sneer. He made his first television appearance on Jimmy and Tommy Dorsey’s Stage Show on CBS in January 1956, but his big break came in June, when he sang back-to-back versions of “Hound Dog,” the second time as a slow-motion bump-and-grind routine, on The Milton Berle Show. Forty million people watched. Berle later claimed he received 500,000 negative letters from viewers—and that was when he knew that Presley was a star. Presley sang “Hound Dog” the same way in September in his first appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show. Sixty million people watched that show—83 percent of all television viewers. By then, “Hound Dog,” with its B-side, “Don’t Be Cruel,” had become the first single to top all three Billboard charts.

The same month, Presley’s first LP, Elvis Presley, was released by RCA Victor; it went to No. 1 on the pop albums chart and stayed there for ten weeks. The song that introduced Europeans to Presley, “Heartbreak Hotel,” entered the British pop charts in May 1956.

In October, Presley’s album was released in Britain on the HMV (His Master’s Voice) label and went to No. 1 there as well. The revolution was accomplished.

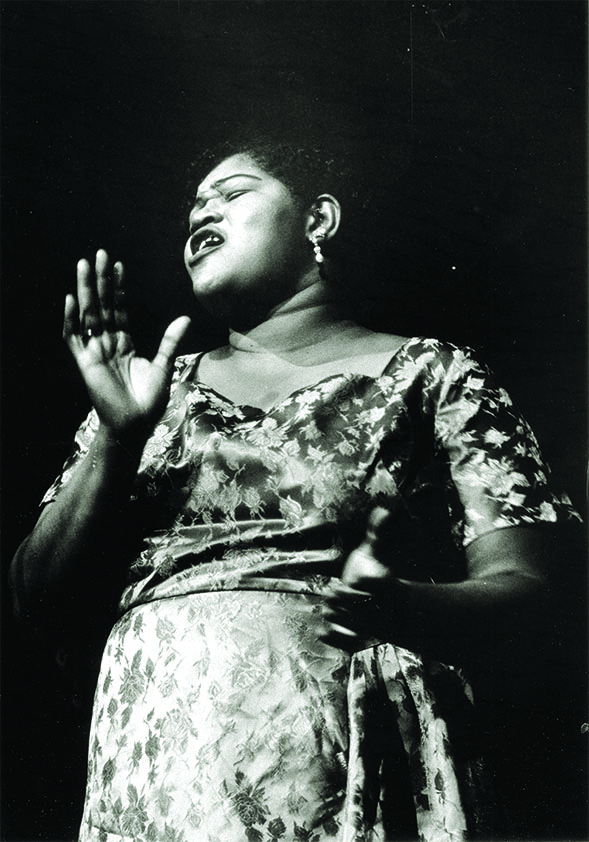

On the level of reception, White performers were adopting a “Black sound.” That is how the charts made things appear. On the level of production, it was a different story. For there is no such thing as a “Black sound” or a “White sound.” “Hound Dog,” which turned out to be one of Presley’s biggest hits, was originally released on the Peacock label by a Black singer named Willie Mae (Big Mama) Thornton in 1953, when it went to No. 3 on the national R&B charts. Thornton didn’t write the song, however. It was written by two Jewish 20-year-olds living in Los Angeles, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, on commission from Thornton’s producer at Peacock Records, Johnny Otis. Peacock was based in Houston, as was Thornton, but the song was recorded in L.A. (Everyone believed that Johnny Otis was Black. In fact, he was Greek-American; his given name was Ioannis Veliotes. He used to say he considered himself “Black by persuasion.”)

As Leiber and Stoller tell the story, they wrote “Hound Dog” “in a matter of minutes.” They thought they had written a raunchy blues number, but when they brought it into the studio, Thornton insisted on crooning the lyrics. Leiber had to sing it for her so she could hear how it was supposed to sound. Otis sat in on the session and played the drums—he was also a musician—and took co-writing credit.

If Thornton’s singing on that record comes across as a parodic imitation of the blues style, that is why. She was copying a sound.

Leiber and Stoller would go on to write many standards of the rock ’n’ roll era, including “Kansas City,” “Jailhouse Rock,” “Yakety Yak,” and “Stand By Me.” “Hound Dog” would be covered well over 200 times, including in French, German, Spanish, and Portuguese, and by four country and western artists. It inspired a parody version, known as an “answer” record, called “Bear Cat,” sung by Rufus Thomas, a Black R&B singer, and recorded on the Sun label by Sam Phillips.

But Presley didn’t cover Big Mama Thornton’s version. He decided to add the song to his repertoire when, during his unsuccessful first Las Vegas gig, he saw it performed at the Sands by an all-White Philadelphia act called Freddie Bell and the Bellboys, who recorded on the Teen label. The group had rewritten Leiber and Stoller’s lyrics to change it from a song about a lover who won’t go away to a song about, actually, a dog. It was a gag number, in other words, and that’s how Elvis performed it—in the goofing-around spirit in which he first sang “That’s All Right, Mama.” When he sang “Hound Dog” on The Steve Allen Show, a basset hound was brought onstage, and Presley sang to the dog.

Presley’s bump-and-grind performances of the song on Berle’s and Sullivan’s shows were therefore tongue-in-cheek, a joke—because Freddie and the Bellboys’ version of the song had erased any sexual content. At that point, the song’s chain of custody extended from the Jewish 20-year-olds who wrote it for a fee, to the African American singer who had to be instructed how to sing it, to the White lounge act that spoofed it, to the hillbilly singer who performed it as a burlesque number. Presley’s version of “Hound Dog” isn’t inauthentic, because nothing about the song was ever authentic. Presley recorded “Hound Dog” in July 1956, in a session—which he directed—requiring 31 takes. The B-side, “Don’t Be Cruel,” has a completely different, doo-woppy, country sound. “Don’t Be Cruel” was written for Presley by Otis Blackwell, who would give him two more songs with the same sound, “Return to Sender” and “All Shook Up.” Blackwell was Black.

Most musicians’ tastes are much more eclectic than their fans’. If he had nothing else to do, Presley sang gospel, as did Jerry Lee Lewis, Carl Perkins, and Johnny Cash, three other Sam Phillips discoveries. (A recording of the four of them jamming in the studio in 1956 was discovered and released several years after Presley’s death.) Muddy Waters sang “Red Sails in the Sunset.” Robert Johnson sang “Yes, Sir, That’s My Baby.” James Brown liked Sinatra and disliked the blues. Leadbelly was a Gene Autry fan. Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” was a cover of a country and western song called “Ida Red,” recorded in 1938 by a White band, Bob Wills and His Texas Playboys. Race had a lot to do with the music business in the United States. It had much less to do with the music.

This article was originally published in the October 2021 issue of American History Magazine. To subscribe, click here.