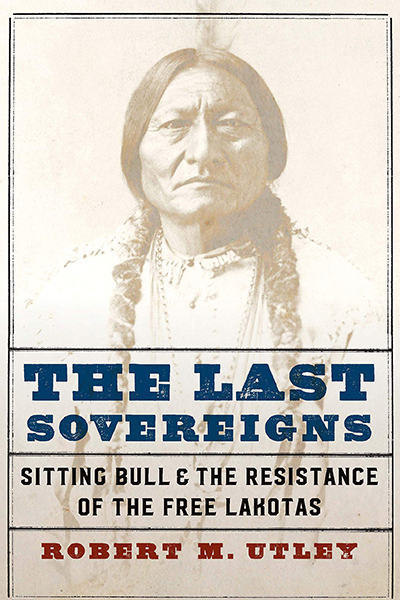

Robert M. Utley turned 91 last Halloween, but the man many consider the dean of Western historians has no plans to retire. His latest book, The Last Sovereigns: Sitting Bull and the Resistance of the Free Lakotas, was published to rave reviews in 2020 by the University of Nebraska Press, which has reissued five of Utley’s books—Billy the Kid: A Short and Violent Life; Frontiersmen in Blue: The United States Army and the Indian, 1848–1865; Frontier Regulars: The United States Army and the Indian, 1866–1891; After Lewis & Clark: Mountain Men and the Paths to the Pacific; and Custer and the Great Controversy: The Origin and Development of a Legend. Utley, who lives with wife Melody Webb in Scottsdale, Ariz., is already at work on his next book. He took time to speak with Wild West about writing and his long career.

Which is the favorite of the books you’ve written?

Which is the favorite of the books you’ve written?

By all odds my biography of Sitting Bull, The Lance and the Shield: The Life and Times of Sitting Bull [1993]. It is my favorite because I think it is a very good book, both for the scholar and the general reader. Other factors: It made a great deal of money and still does; it was my first handled by a literary agent, Carl Brandt, who died in 2013; and it spawned The Last Sovereigns: Sitting Bull and the Resistance of the Free Lakotas.

What more have you learned about Sitting Bull?

I did not examine many new sources because of my inability to travel to libraries and archives. But I retained all my notes in my computer. Calling them up and printing them chronologically, I gave them fresh study based on 30 years of professional maturity.

What draws you to Sitting Bull and his people?

I believe Sitting Bull resonates with the reading public now more than ever before. A host of excellent studies of the Little Bighorn have been published in the past 30 years, giving Sitting Bull’s stature even greater public recognition. This is inherent throughout Pekka Hämäläinen’s groundbreaking Lakota America. Moreover, I have always been enamored by the North-West Mounted Police, and their relationship with Sitting Bull was crucial. After 24 books, searching for what to work on next, I settled on Sitting Bull, as truly, of all the great chiefs, he was indeed “The Last Sovereign.”

Will you continue writing books?

Yes, I am going to continue. Like The Last Sovereigns, however, they have to flow out of work I have done in the past, since I am confined at home in a wheelchair. The next one, in progress, is about selected Indian battles and how the Army performed. Emphasis will be on controversy they inspired, especially the women and children killed and whether that could have been prevented.

When did you know you wanted to be a historian?

I didn’t think of it as being a historian, but when I was a seasonal ranger-historian at Custer Battlefield National Monument, during my college summers (1947–52), I wanted to write history and did, although it was completely amateurish. A visitor to the battlefield loaned me $500. I wrote a pamphlet about Custer’s Last Stand, designed it myself and had it printed. In a brazen conflict of interest the woman who ran the souvenir shop near the battlefield sold it for 75 cents a copy and informed all customers it was written by the “battlefield boy” at the top of the hill. All 600 copies sold out, and the loan paid. Find one now and it will cost you several hundred dollars.

‘My research and recommendations played a crucial role in bringing into the [National Park Service] system Fort Bowie, Fort Davis, Hubbell Trading Post, Golden Spike and Chamizal. As chief historian in Washington, D.C., of course, I was concerned with all units of the system’

How did your work with the National Park Service affect your career path?

I became wedded to the Park Service at Custer Battlefield. After four years in the Army I returned in permanent status as historian of the Southwest Region, Santa Fe. During my six years there I did historical work on proposed units of the [National Park Service] system. My research and recommendations played a crucial role in bringing into the system Fort Bowie, Fort Davis, Hubbell Trading Post, Golden Spike and Chamizal. As chief historian in Washington, D.C., of course, I was concerned with all units of the system.

To backtrack, my master’s thesis at Indiana University was what is now Custer and the Great Controversy. After the Army I intended to return to Indiana University for a doctorate, and the dissertation topic was what later became Yale’s Last Days of the Sioux Nation. Most of the research for that was done while I was a historian for the Joint Chiefs of Staff in the Pentagon; in the evenings, still in uniform, I worked in the National Archives. I chose to return to the Park Service rather than get a doctorate. As my work broadened out into the whole West, I worked on books in the evenings and on weekends, but never on taxpayers’ time.

How did you choose the topics for your books?

Some of the topics picked me. The frontier Army was part of Macmillan’s Wars of the United States series. Lou Morton was general editor. He picked me to do the frontier Army, which turned into two volumes. After those, Ray Billington asked me to do The Indian Frontier for his Histories of the American Frontier series. After retirement in 1980 I sought something to make money. After a visit to Lincoln I thought the Lincoln County War would make money. It didn’t, but the outgrowth, Billy the Kid, did. [The University of Oklahoma Press] was launching a series of brief biographies and asked me to do Custer as a guide for the series. The most successful book, the biography of Sitting Bull, was my own idea, and its success was partly because literary agent, Brandt, called me and suggested we get together; he sold Sitting Bull to Henry Holt. When Melody became superintendent of the LBJ National Historical Park in Texas, the proximity of sources for the Texas Rangers prompted that subject. The mountain men blended nicely with Melody’s assignment to Grand Teton National Park. Sitting Bull suggested Geronimo. And so it went.

How does your writing approach vary between scholarly and commercial projects?

Scholarly projects are usually done by doctoral students hoping to become a university professor. Therefore, the doctoral dissertation requires deep and wide research and learned interpretation along with extensive documentation. At meetings of professional associations authors mingle with publishers, usually university presses, and seek to have their dissertation accepted.

For a commercial press, an author may write on nearly any subject, so long as it is well researched and written for a wide, nonprofessional audience. Such projects are almost always handled by a literary agent, who polls a number of publishers to ascertain which is interested and will offer the best royalty arrangement.

What is the future of Western nonfiction publishing?

It is excellent, so long as the book deals with a topic of general interest, is well grounded in research and is well written. Good examples are the works of Jerome Greene, especially American Carnage, about Wounded Knee. WW

This interview was published in the February 2021 issue of Wild West.