After serving as a junior officer, ‘Rob’ Lee wrote a renowned chronicle of his father’s life

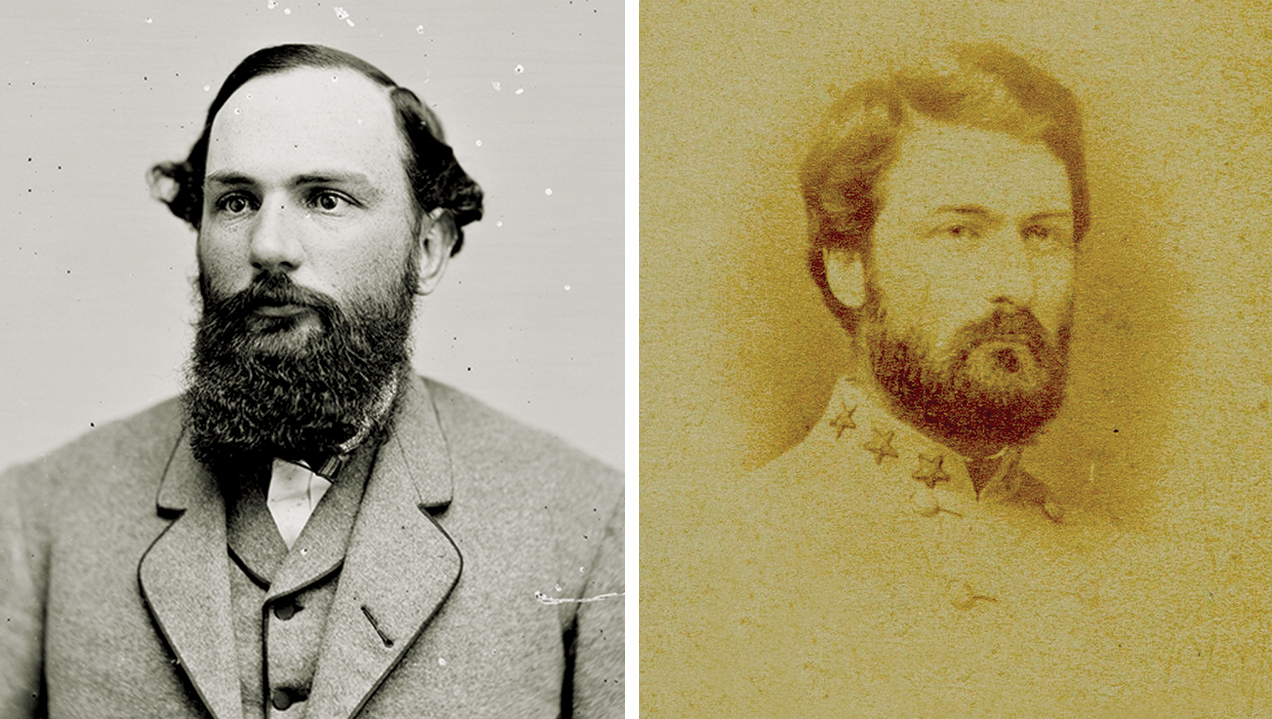

IT WASN’T EASY LIVING in the shadow of the Confederacy’s greatest general, but Robert E. Lee Jr. had an interesting and accomplished Civil War career. He fought in the artillery and cavalry and rose to the rank of lieutenant. He later became one of his father’s greatest chroniclers through the publication of Recollections and Letters of Robert E. Lee in 1904.

Robert Edward Lee Jr. was the sixth of his parents’ seven children. The youngest of three boys, he was born October 27, 1843, atArlington Plantation, the home of his mother, Mary Anna Randolph Custis Lee, daughter of George Washington Parke Custis, the adopted grandson of George Washington. Rob’s other grandfather was Revolutionary War cavalryman “Light Horse” Harry Lee.

The family’s military tradition had its challenges. As a Regular Army officer, the elder Lee was gone for long periods conducting engineering work on military defenses in Virginia, New York, Maryland, and Georgia. When the Mexican War broke out, Captain Lee served as an engineer in Winfield Scott’s forces. In Recollections and Letters, Rob said his earliest memory of his father was of him returning home from Mexico after an absence of nearly two years. According to Rob, his father didn’t recognize him and kissed Rob’s playmate by accident. It would not be the last time Rob’s father failed to recognize his son.

As was true of the other Lee children, Rob received an excellent education. He first attended school in Baltimore, while his father was serving at Fort Carroll. When Robert E. Lee moved to West Point, N.Y., in 1852 to serve as superintendent of the U.S. Military Academy, Rob followed. Rob remembered his father helping him with Latin and teaching him how to ride a horse. But Rob wrote, “I saw but little of my father after we left West Point” in 1855, when the senior Lee was ordered to St. Louis in preparation for his next assignment out West, chasing Comanche warriors across the hot and arid Texas plains.

Despite his father’s absences, “it was impossible to disobey him,” Rob recalled. “My mother I could sometimes circumvent and at times took liberties with her orders…but exact obedience to every mandate of my father was a part of my life and being.” From November 1857 to February 1860, Robert E. Lee returned to Arlington to settle the estate of George Washington Parke Custis. Young Rob had another couple of years to enjoy with his father.

In contrast to his father and brothers, Rob was not interested in pursuing a military education. He attended the University of Virginia, which in the prewar period was a raucous, all-male institution where students drank, shot pistols, and broke things. Rob might have been full of youthful energy, but like his father, he was also religious. In May 1860, he underwent a spiritual conversion. “How are you getting along with your God,” he wrote his sister Mildred in January 1861. “O! my sister,” he said, “neglect not him. I have suffered much from neglecting him.”

When the Civil War broke out, Rob—not yet 18 years old—was an eager volunteer. In the spring of 1861, young men from the University of Virginia organized military companies, and Rob became a commissioned officer in the “Southern Guard.” He marched with this unit all the way to Winchester before Governor John Wise ordered the students back to Charlottesville. In December 1861, Rob wrote there were only 50 students left at the university—down from 650 the previous year—because so many had enlisted in the Confederate Army.

Rob grew up in a thriving slaveholding society, and his racial views reflected that reality. In January 1862, a few months before he reenlisted, Rob visited White House plantation, the home of his brother William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, better known as “Rooney.” Rob wrote to Mildred that “the most delightful thing about the place is the set of negroes. They are the real old Virginny kind, as polite as possible devoted to their master & mistress, who are devoted to them & who do every thing for them.”

On March 28, 1862, Rob joined the Rockbridge Artillery as a private, and with that unit experienced his first fighting in the Shenandoah Valley. During the first few weeks of his service, the Confederate Army was in a difficult moment of transition. In April, the Confederate Congress passed a controversial conscription act, the first in American history. The act drafted men from the ages of 18 to 35 and kept them for three years or until the end of the war. The act led to the reorganization and consolidation of regiments. “The whole army seems very much dissatisfied,” Rob wrote to his father on April 23. He noted there were “a good many desertions among the militia & the valley men who refuse to leave their homes behind them.” Rob himself was not discouraged, and he looked down on those men of wavering patriotism.

In May at Front Royal, Va., Confederates routed a much smaller force of Federals under Colonel John Reese Kenly. Rob wrote of overrunning Federal camps and the men helping themselves to bacon, sugar, coffee, and other luxuries. We “got all kinds of sweetmeats,” Rob wrote his father, “the most delicious canned fruit of all Kinds ginger cakes by the barrels sugar candy & all Kinds of ‘nick nacks.’” Rob said he made a “hearty meal” of “bread & butter ginger cakes & sugar wh[ich] helped me out, for I was nearly starved.” The young artilleryman said the Confederate damage amounted to $100,000.

Victory did not erase the harsh realities of war. Rob saw one of his friends badly wounded in the face at Front Royal. As for himself, he was exhausted. “I think I have been through as hard a time as I ever will see in this war,” he told his father. “For twenty four days we have been marching & this is the fourth day we have rested Through rain mud water woods up & down mountains & for two weeks half starved.” The hard fighting, though, energized him. “I am now as hearty as a buck feeling better than I ever did in my life,” he reassured his father.

Rob did not see General Lee again until the Seven Days Battles. By then, his father had been put in command of the Army of Northern Virginia and was fighting to drive Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac from the outskirts of Richmond. Rob remembered that by then, “short rations, the bad water, and the great heat, had begun to tell on us, and I was pretty well worn out.”

At the Second Battle of Manassas, Rob, serving as the “No. 1” man in charge of ramming artillery rounds down his cannon’s barrel, was again in the thick of combat. “My face and hands were blackened with powder-sweat,” he recalled, “and the few garments I had on were ragged and stained with the red soil of that section.” Rob encountered his father on the battlefield and managed to get his attention. “Well, my man, what can I do for you?” he remembered his father saying. “Why, General don’t you know me?” Rob replied. Once his father realized who he was talking to, he was “much amused at my appearance and most glad to see that I was safe and well.”

Shortly after Second Manassas, the Army of Northern Virginia headed north toward the Potomac River and Maryland. During the busy days of marching, Rob recalled he “occasionally saw the commander-in-chief, on the march, or passed the headquarters close enough to recognise him and members of his staff, but as a private soldier in Jackson’s corps did not have much time…for visiting….”

His next opportunity to talk to his father came on September 17, the day of the notorious Battle of Sharpsburg. During that bloody fight, when 23,000 men became casualties, Rob remembered that “our battery had been severely handled, losing many men and horses. Having three guns disabled, we were ordered to withdraw, and while moving back we passed General Lee and several of his staff, grouped on a little knoll near the road….Captain Poague, commanding our battery, the Rockbridge Artillery, saluted, reported our condition, and asked for instructions.”

The general listened to Poague’s report and told him to take his damaged guns to the rear, but to prepare his remaining cannon for more action. As he talked to Poague, Lee’s eyes drifted over the battle-worn men on the battery, once again apparently not recognizing his youngest son. Rob recalled that he approached his father, said hello, then asked, “General, are you going to send us in again?” Replied the commander, “Yes, my son, you all must do what you can to help drive these people back.”

By the fall of 1862, Rob, his father, and his brother and cavalry officer Rooney had survived several bloody campaigns, but the family suffered loss all the same. In October, his sister Annie died of disease in North Carolina, where she had fled to escape the ravages of war in Virginia. “I shall never see her any more in this world,” Rob wrote of Annie.

As much as possible, the family tried to stay together. Rooney was promoted from colonel of the 9th Virginia Cavalry to brigadier general and leadership of North Carolina and Virginia troopers. Rob became a lieutenant and one of Rooney’s staff officers and remained optimistic about the Confederacy’s future. “I think we’ll whip old Burnside badly when we meet him,” he wrote in late November 1862. Events proved him correct. Lee’s forces soundly defeated Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside in December at the Battle of Fredericksburg.

Months of relative inactivity followed. Rob fought at Chancellorsville on May 1-3, 1863, but he did not march north with the Army of Northern Virginia into Pennsylvania during the Gettysburg Campaign. That might have been because Rooney was wounded at Brandy Station on June 9 and captured soon thereafter and sent to a Northern prison, where he languished for months. With his brother out of the army, Rob worked for a while with the Ordnance Department in Richmond.

Rob was not depressed by the news of his father’s July defeat at Gettysburg. Later that month, he told his mother that “the men & officers are in very good spirits & very desirous of establishing their fame firmly, which they think has been a little shaken at Gettysburg.” By then, Rob had rejoined the cavalry, serving in Colonel John R. Chambliss’ 13th Virginia Cavalry, and he defended his fellow horsemen against accusations that the cavalry “never does anything.” “Truth is we do all the hard work of the Army,” he said, noting there was “freedom in this branch which is delightful.”

Rob remembered that at the time of the 1864 Overland Campaign, morale was still high in the Army of Northern Virginia. He wrote, “it never occurred to me, and to thousands and thousands like me, that there was any occasion for uneasiness.” The men of the Army of Northern Virginia “firmly believed that ‘Marse Robert’…would bring us out of this trouble all right.” Rob was wounded at the May fighting near Spotsylvania, but he recovered and rejoined his command. In a July 1864 letter to his sister Agnes, he wrote of soldiers getting plenty to eat, and he was impatient to “turn our horses out on the fine grass in Maryland & Pennsylvania.”

During the Petersburg siege, on August 15, 1864, he was wounded slightly in the arm at the Second Battle of Deep Bottom. The wound took Rob out of action for three weeks.

By 1865, Rob’s outlook had grown darker and he was pessimistic about his future. “I don’t know whether I shall ever see you again,” he told his sister, Mildred. But he could still be funny, warning Agnes in March: “Don’t let Sheridan get my trunk,” referring to Union Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan.

In the final days of the war, Rob had a horse shot from under him, an event he remembered happening on April 2 or 3. Thankfully for him, he was cut off from the rest of the army. He said he was “surprised” when he heard of the news of the surrender. He rejoined his command and accompanied the remnants of the Jefferson Davis government to Greensboro, N.C. That was as far as he made it. He eventually returned to Richmond and was paroled in May 1865.

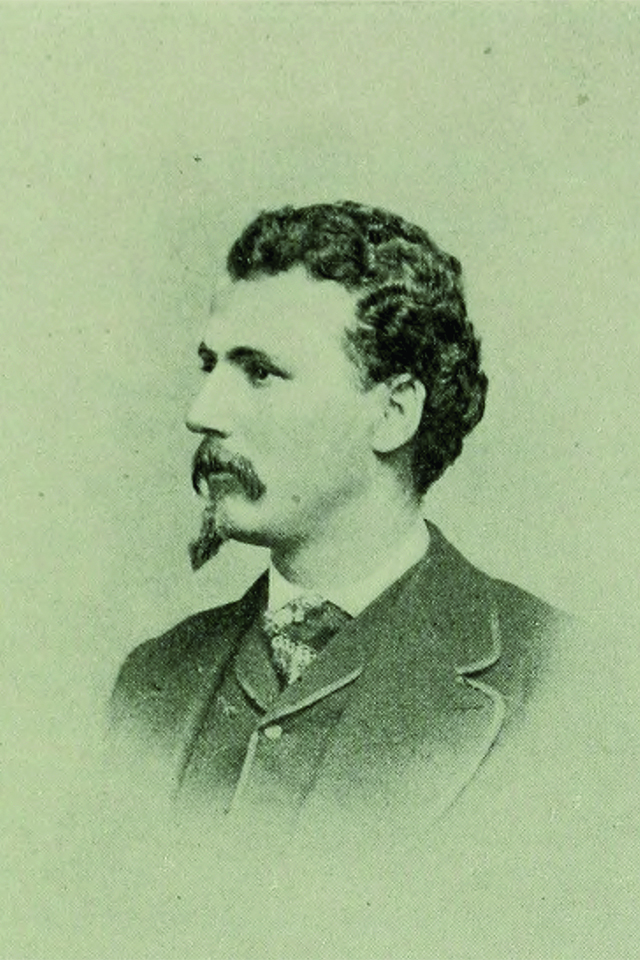

With the South devastated, Rob tried his hand at farming. He settled in King William County, Va., roughly 40 miles east of Richmond. As the owner of “Romancoke,” he ran a small plantation on the Pamunkey River. The estate was left to Rob in 1857 by his grandfather, George Washington Parke Custis. At Romancoke, Rob—far from his family in Lexington—found himself a lonely bachelor and struggling farmer.

Unlike his oldest brother Custis, who became president of Washington and Lee University, and Rooney, who later became a U.S. congressman, Rob kept a low profile after the war and his racial views had not progressed beyond condescending references to African Americans. In February 1866, he told a sister about “Old Coon,” a black woman helping him keep house. A year later, he dismissed the plight of the freed people of the South, saying, they were “stirred up by baptizing & politics,” but added “that theory would never be demonstrated by Cuffee.”

He still received advice from his father. “You must have a nice wife,” the elder Lee told him in August 1867. “I do not like you being so

lonely. I fear you will fall in love with celibacy.” General Lee traveled to Romancoke several times to see his bachelor son. Rob apparently cared little about entertaining, and after one trip General Lee decided his son needed a proper set of silverware. The general last visited Rob in the spring of 1870.

The news of his father’s death on October 12, 1870, hit Rob hard. After the general’s death, he lamented his own “selfishness & weakness” and praised his father for the “example of true manliness he set me all through his life.” In contrast, he felt he had “done so little for him.”

Rob’s uncertain finances, the shabbiness of his estate, and the fact that he was far from family and city life slowed his prospects of finding a wife. After a long courtship, in November 1871 he married 23-year-old Charlotte Taylor Haxall, but the marriage to “Lottie,” as she was known, proved brief. She died of tuberculosis on September 22, 1872. “I try to believe that all is for the best,” he wrote after her death, “but it is very hard—hard to believe, harder still to feel so.” A year later, Rob lost his mother, who had suffered from debilitating ill health. A few weeks before her death, Rob’s sister, Agnes, had also died.

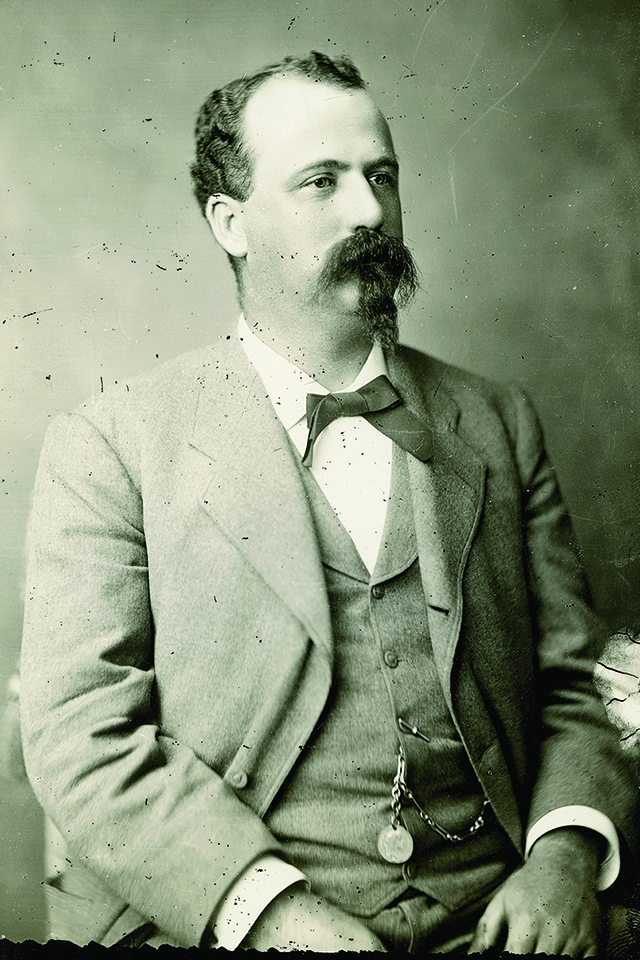

In 1875, Rob departed for England with his sister Mildred. He stayed there for a year. Rob eventually moved from Romancoke to Washington, D.C., where he worked in the insurance business. In March 1894, Rob married Juliet Carter, the daughter of Colonel Thomas H. Carter, a Virginian who had served in the Army of Northern Virginia’s artillery.

Rob and Juliet had two daughters, Anne Carter (1897-1978) and Mary Custis (1900-1994). In 1904, Rob published Recollections and Letters of General Robert E. Lee. The book included transcriptions of his father’s letters, recollections of his spoken words, and anecdotes drawn from Rob’s memories of those of his older siblings. The book was well received and remains essential reading for Lee scholars.

Rob died on October 14, 1914, and he is buried with his family in the Lee crypt in Lexington. Robert E. Lee biographer J. William Jones wrote of him, “No braver or more chivalric man ever lived, and his death is lamented by his surviving comrades of the war, and by a host of friends.”

In many ways, Robert E. Lee Jr. was a typical Confederate soldier. He was an unmarried enlisted man in his 20s who fought in the ranks and a defender of the racial status quo. He survived the war, though he saw many of his friends and comrades killed.

In other ways, his life was atypical in that he was the son of the Confederacy’s greatest warrior and a member of one of the South’s most celebrated and elite families. An unsuccessful farmer after the war, the ex-Rebel moved, ironically, to the federal capital of Washington, D.C., to seek better financial opportunities.

Rob’s career may have been humble compared with others of his generation, but his letters provide an important link between the pre- and postwar South, and he was the liveliest and funniest writer of any member of his family. His Recollections and Letters of Robert E. Lee remains an important source on his famous father.

Colin Woodward is the author of Marching Masters: Slavery, Race, and the Confederate Army During the Civil War. He lives in Richmond, where he is host of the history and pop culture podcast “American Rambler.” He is revising a book on country singer Johnny Cash.