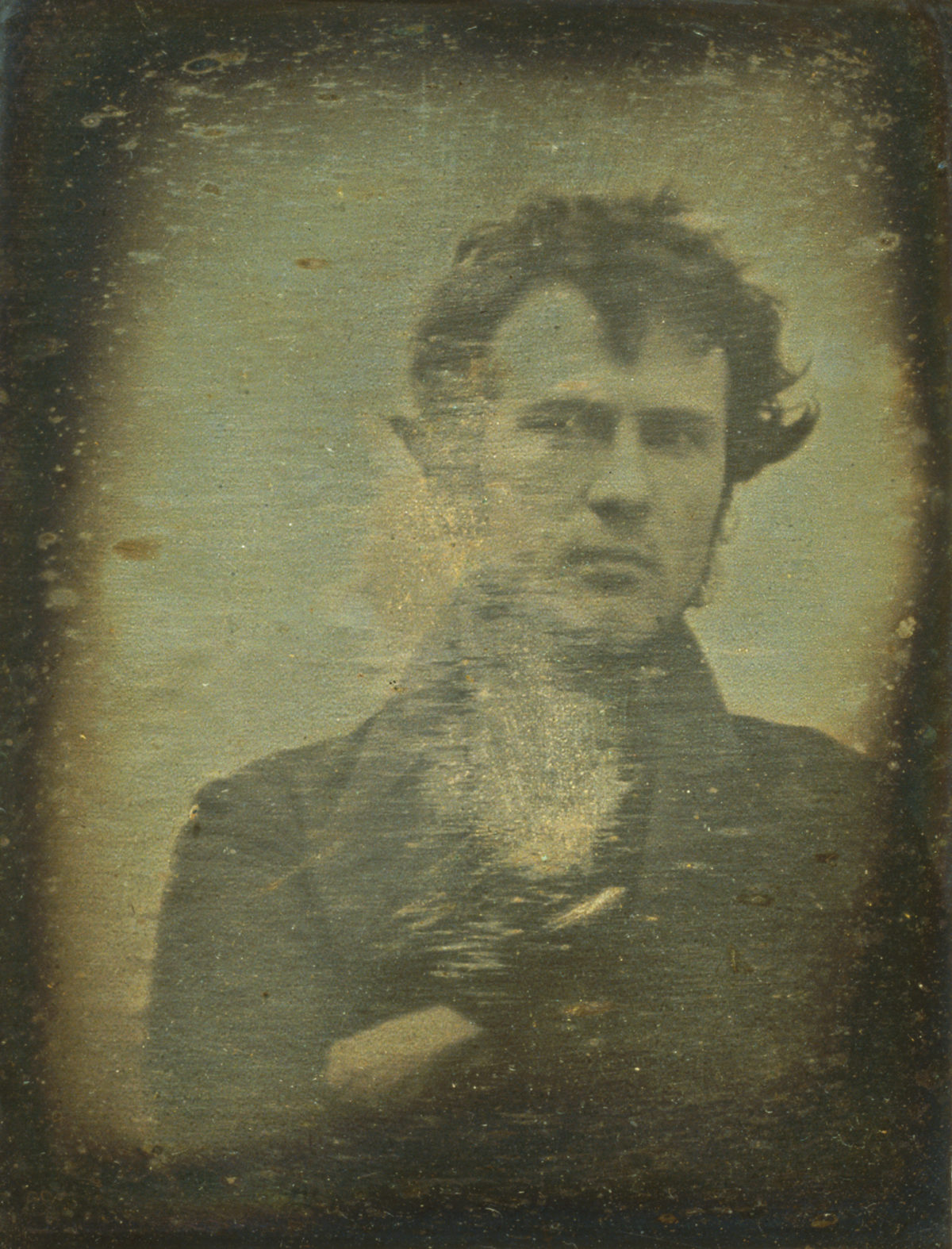

In 1839, Robert Cornelius took the first photographic self-portrait. What in the Philadelphian’s era was an enforced moment of somber motionless reflection, lest blink or breath blur the image being exposed on a chemically treated silver-coated plate, today is casually snapped in a fraction of a second by billions in the form of “selfies.” An innovator in photographic method, Cornelius established a successful portrait studio in Philadelphia at 8th and Market Streets. He soon returned to work at his father’s lighting and lamp firm, but his brief stint as a photographer opened doors, technical and aesthetic, to a revolution in the new medium. Cornelius also had a career as a metallurgist that traces the rise and fall of innovations in another product involving light: lamps.

Cornelius, born in 1809, was son of Christian Cornelius, a watchmaker’s son turned expert in silver plating who at 13 had emigrated from the Netherlands to Lancaster, Pennsylvania. He is said to have started out in Philadelphia in 1827 by melting down the family silver dishes. The company would create brass lamps, chandeliers, and candlesticks, including a spring-driven candlestick that cleverly kept a wick and its flame at a constant level. The elder Cornelius later moved into more elaborate lighting apparatus. His business enabled him to send son Robert to private schools that trained the youth in chemistry, geology, and drawing. In 1831, Robert, 22, started working for his father.

The young man developed a sideline in 1839 upon learning how French inventor Louis Daguerre had developed a technique for capturing images on pieces of silver-plated metal.

The earliest photographic images necessarily were Parisian cityscapes because the plate needed many minutes to register a sharp exposure on its treated surface; animals and passersby moving across the frame appeared as ghostly smudges. Samuel Morse, seeing an early Daguerre image, wrote in April 1839, “…the exquisite minuteness of the delineation cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it.” Details of the spectacular process soon reached the United States, where the younger Cornelius may have read about it in the August 1839 issue of the journal of the Philadelphia-based Franklin Institute. He and kindred spirits immediately began experimenting.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Working in his home with a tin box and lenses meant for opera glasses, in October or November 1839 Cornelius exposed and chemically stabilized, or fixed, an image of himself on a silver-coated plate of his own devising. Recognized as the first photographic portrait, this artifact is remarkable not only for its technical excellence—due to its creator’s expertise at fashioning and polishing a fine silver plate—but for the way in which the 30-year-old Cornelius, young and vibrant, seems to be catching himself in the moment, tousled hair, popped shirt collar, and all. Casually positioned in front of the camera, he has used one hand to uncover the lens and then kept still to immortalize himself.

Others were tinkering as well, and newly minted photographers were soon producing what became known as daguerreotypes—images on metal plates about 5”x7” in size set in wood or gilt metal frames. But for an image to be its sharpest, a subject had to be inanimate or able to sit utterly still for five, even ten minutes, producing a stiff and unnatural look. Some photographers had subjects sit with eyes closed or head gripped by an armature; others dusted subjects’ faces with flour to heighten contrast.

While fellow experimenters were working on contrast, Cornelius was tackling the chemistry of recording light.

His circle included Dr. Paul Goddard, who aided Cornelius in figuring how to dramatically cut exposure time. Photographic plates produced images on a thin layer of silver coated with iodine crystals that reacted to light. Goddard suggested adding bromine, which reduced exposure time to as little as 30 seconds.

The men shared the discovery with the local scientific society—once they had cornered the local bromine market—and opened a studio in Philadelphia in May 1840. Two large mirrors positioned outside the studio were angled to direct light within, filtered through purple glass to reduce glare.

Customers needn’t be rich. A daguerreotype could be had for $5, a fraction of what a painted portrait cost. Yet photographs seemed not to reduce demand for painted portraits, and painters often took daguerreotypes of subjects for reference instead of putting customers through hours-long sittings. Rival studios opened.

Perhaps tired of the medium and dismayed by competition, Cornelius closed his studio in 1842. His output is unknown, but a recent survey identified 54 Cornelius daguerreotypes in museums and private collections.

A recent survey of Cornelius images found there to be 54 of them in the collections of private individuals and museums.

Philadelphia became a bastion of studio photography, by 1849 counting more than 40 studios in the city center, where photographers converted lofts to studios with reflective white walls and large windows to direct light.

Cornelius returned to the family business, which was thriving by manufacturing large lamps renowned for their brightness, sturdiness, and beauty and often were fueled by whale oil in a reservoir surrounded by prisms to intensify the glow. The 1840s saw the beginning of whaling’s heyday. Spermaceti, a dense slippery substance from a sperm whale’s head, burned bright and long and was one of the prime products of the hunt. Spermaceti eclipsed a succession of other substances—beeswax, beef tallow, pork lard, colza oil (from rapeseed), oil from whale blubber, and camphene, a derivative of turpentine—during 1840-1870 becoming the preferred lamp fuel.

Cornelius patented a type of solar lamp, said to rival the sun for brightness, that burned lard and salvaged kitchen grease. He was granted more than 20 patents. As gas light gained popularity, the Cornelius company adapted, manufacturing large gas-powered lamps, chandeliers, and ostentatious assemblages known as girandoles, from the Italian for “to turn.”

Christian Cornelius retired in 1851, and Robert Cornelius and relatives carried on. By 1855, the Cornelius company was employing 500 workers in two large factories in Philadelphia. The enterprise is most remembered as the premier manufacturer for grand girandoles marketed worldwide.

Cornelius lamps, installed in state capitols and in the U.S. Senate and three rooms at the White House, were a million-dollar business.

With the discovery in 1859 of petroleum in Titusville, Pennsylvania, much of the market for table lamp fuel shifted to kerosene made from petroleum. According to historical lighting expert Dan Mattausch, one Robert Cornelius patent was for a kerosene table lamp, but a competitor brought out a far cheaper version that won consumers’ favor. In 1877, Cornelius retired, and with him, perhaps, the spark of innovation. The company continued to make showy gas fixtures, sometimes depicting American icons such as George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and Andrew Jackson, or a generic hunter.

Robert Cornelius left his mark nonetheless. As he put it in 1839, “I made a likeness of myself, and another one of some of my children in the open yard of my dwelling, sunlight bright upon us, and I am fully of the impression that I was the first to obtain a likeness of the human face.”

This article appeared in the Winter 2023 issue of American History magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.