A Georgia showdown between former West Pointers adds drama to the March to the Sea

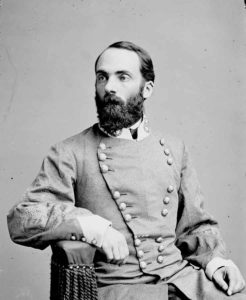

Joe Wheeler is considered by many Civil War historians, somewhat unfairly it seems, the Confederate Army’s most overrated general. In their opinion, as Edward G. Longacre writes in his 2006 book A Soldier to the Last, Wheeler was an inept tactician—a commander who “failed to inspire or discipline his troops…and whose ambition-driven support of equally inept superiors [e.g., Braxton Bragg] retarded rather than advanced Confederate fortunes” in the Western Theater. The criticisms have some merit, Longacre concedes, but are also overblown. What cannot be disregarded in any assessment of Wheeler is the part he played defending against Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 1864 March to the Sea and the 1865 Carolinas Campaign. Sherman, for one, was not about to underestimate Wheeler and his small, yet seasoned, Cavalry Corps, and he wanted to make sure his own cavalry commander, Brig. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick, did not either. An earnest duel between Kilpatrick and Wheeler, which actually had begun a few years earlier when the two were cadets at West Point, would play out over several months and provide a fascinating sideshow as Sherman rolled through Georgia in late 1864 and the Carolinas in early 1865.

[dropcap]A[/dropcap]fter the capture of Atlanta on September 2, 1864, Sherman spent the next 10 weeks destroying Confederate supplies and infrastructure, consolidating his own resources, and contemplating his next move. Confederate General John Bell Hood’s Army of Tennessee, meanwhile, did whatever it could to disrupt Sherman’s supply lines. But in late October, Hood had his army retire into Alabama. Sherman, presuming from comments made by Confederate President Jefferson Davis that Hood intended to invade Tennessee, saw this as an opportunity. Instead of chasing Hood, he would lead his Military Division of the Mississippi on a devastating march through Georgia. Sherman dispatched the Army of the Cumberland (minus two corps), under Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, to defend Tennessee and kept four corps, comprising the Army of the Tennessee and the Army of Georgia, back in Atlanta. On November 15, he began moving toward Savannah.

As expected, Hood invaded Tennessee. The two wings of Thomas’ Army of the Cumberland at that point were separated by about 75 miles, and Hood hoped to strike before they could come together. The invasion led to disaster, however—first with a severe Confederate defeat at the Battle of Franklin on November 30, 1864, then a second at Nashville on December 15-16.

The back-to-back defeats left the Army of Tennessee with more than 10,000 casualties and roughly only 20,000 demoralized men in the ranks. At his own request, Hood was relieved of command, and the remnants of his army were mostly scattered back east.

The decision to invade Tennessee left only about a third of Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s 45,000-man Department of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida as well as Wheeler’s 3,000-man Cavalry Corps available to resist Sherman’s 62,000-man force. It didn’t help that most of the Rebel defenders were militia and not veteran or reliable troops.

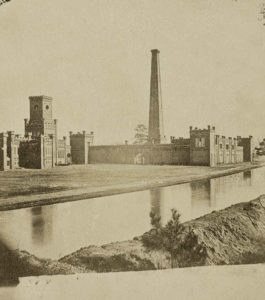

When Maj. Gen. O.O. Howard’s Army of the Tennessee and Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum’s Army of Georgia moved out of Atlanta on November 15, it wasn’t clear to the Confederates where Sherman was headed. Sherman hoped Hardee would consider Augusta a feasible destination. It was a major industrial center, home of the South’s largest powder works and several important textile mills, and also the terminus of the Georgia Railroad. This line linked up with the Tennessee River at Chattanooga, Tenn., and until cut by Sherman’s capture of Atlanta, provided access from the Georgia interior to the Mississippi River.

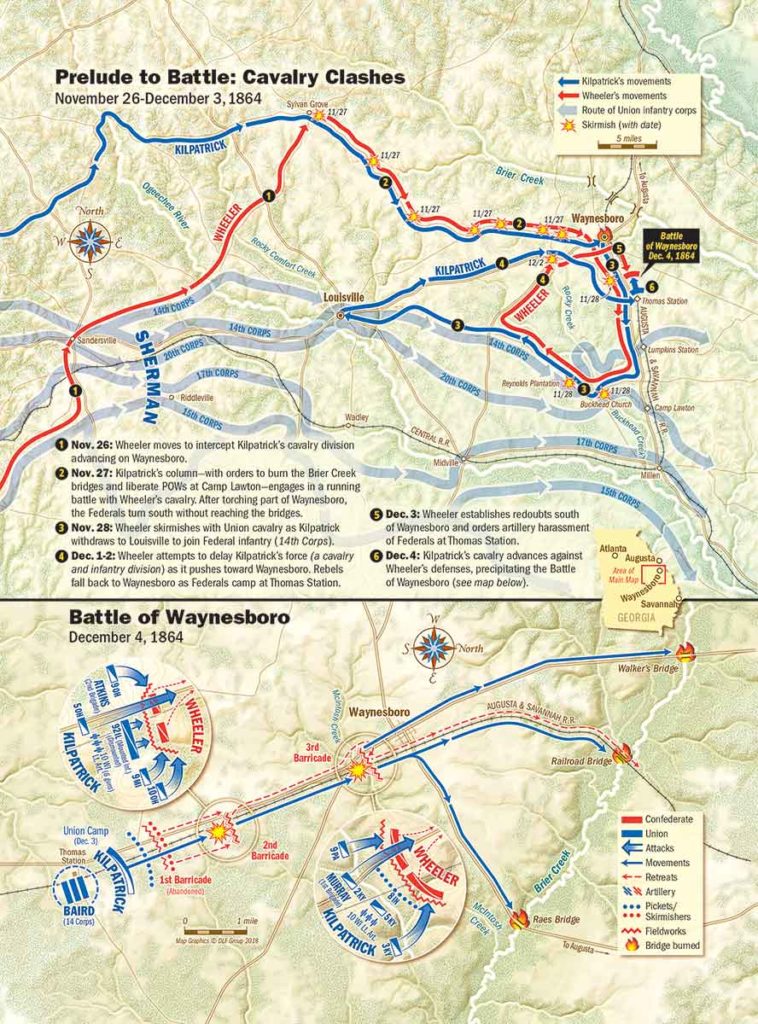

It took Howard’s and Slocum’s armies—marching as the right and left wings on parallel routes, respectively, and facing only slight opposition—eight days to reach the Georgia capital of Milledgeville, about 100 miles to the southeast. On November 24—in an effort to divert attention from his army’s true destination, Savannah—Sherman sent Kilpatrick’s 5,000-man cavalry division, along with a single infantry division under Brig. Gen. Absalom Baird, from Brig. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’ 14th Corps, on a feint toward Augusta. Kilpatrick was to ride into Waynesboro, 30 or so miles from Augusta, and destroy the rail lines there, before heading to the south to liberate Union prisoners being held at Camp Lawton. From there, he was to rejoin the main army as it proceeded to Savannah.

Hardee instructed Wheeler’s cavalry, and a small contingent of Georgia state troopers, to track down and stop Kilpatrick. Wheeler learned late in the day November 26 that Kilpatrick’s force had crossed the Ogeechee River, undoubtedly heading, in Fighting Joe’s mind, to Augusta. That was particularly vexing to Wheeler. Augusta was his hometown, and he felt he had a personal incentive to defend it.

Wheeler, much more of a by-the-book soldier, also would be pleased if he could get the better of the rogue warrior Kilpatrick—known now even by his own men as “Kilcavalry” for his tendency to order reckless cavalry charges. The two had been together at West Point in 1859, when both were eligible for conduct honors. Two years behind and a better student, Kilpatrick had no demerits that year, compared to Wheeler’s (still-noteworthy) six.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Kilpatrick led a brash saber charge and managed to escape capture, though he lost his hat in the process[/quote]

While at West Point, Kilpatrick was also aggressively outspoken in his anti-Southern views, often prompting fights with Southern cadets. Though there is no record he ever fought with Wheeler, the Georgian no doubt would have been angered by such smears.

Over eight days, beginning on November 27, Wheeler and Kilpatrick engaged in a series of cavalry clashes in the vicinity of Waynesboro. That first day, the Federal troopers had had some success tearing up and destroying sections of railroad track and burning some buildings in Waynesboro. When Kilpatrick learned the Union prisoners at Camp Lawton had been moved elsewhere, he prepared to leave the town and head south to rejoin Sherman.

At dawn on November 28, with his men already on the move, Kilpatrick was nearly captured, along with members of the 9th Michigan Cavalry and the 8th Indiana Cavalry, when they became isolated during an attack by Wheeler’s troopers. Kilpatrick led a brash saber charge and managed to escape, though he lost his hat in the process.

Kilpatrick established a solid defensive position three miles west of the Buckhead Church and fended off another attack by the Rebels as night approached. For the next two days, a stalemate ensued. Still convinced the Federals were headed for Augusta, Wheeler had his troopers occupy roads leading in that direction.

On December 1, Kilpatrick renewed the offensive, making sure he would do so this time with the aid of infantry. Baird’s 3rd Division accompanied Kilpatrick as it moved out of Louisville in the morning. Although Wheeler’s main body remained in position behind Rocky Creek, several of his detachments contested the advance. “During the day,” Baird wrote, “[there was] considerable skirmishing with the enemy’s cavalry, with a loss on our side of 3 men killed and 10 wounded.”

Baird and Kilpatrick, on the far left of the advance, continued their combined effort to deal with the Rebel cavalry. They crossed Buckhead Creek and pushed back the Confederate pickets. A saber charge by a battalion from the 5th Ohio Cavalry cleared the way. Reaching Rocky Creek, Kilpatrick’s cavalry stopped to permit an infantry attack. Baird extended his lines and found a crossing point. After the 74th Indiana crossed the creek, Wheeler withdrew toward Waynesboro. Once across the creek, Baird turned the column southeast toward Thomas Station.

On December 3, Wheeler moved back through Waynesboro and engaged Federal pickets. Kilpatrick and Baird had orders to turn north toward Wheeler’s position. The flanking column was to “destroy the bridge over Brier Creek” on December 4. That ended up setting the stage for the second cavalry clash around Waynesboro.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]A shout went up all along the line, and the glitter of sabers following the fire of carbines showed the mettle of the men[/quote]

During a restless night, Baird sent a report to his corps commander, Davis, and expressed his disdain for the cavalry, which he believed leaned too much on the infantry for support. Baird alerted his commander to Wheeler’s increased activity, the presence of Confederate artillery, and signs of entrenching. “Kilpatrick thinks that the fight of the campaign will take place here today,” he wrote. “I do not see it in that light, but will support him.” There were severe limitations on how much Baird could do, however, as his ammunition supplies were desperately low.

Later in the day on December 3, Wheeler again attacked Kilpatrick near Buckhead Creek, driving off the Federals and halting their destruction of the railroad there. Kilpatrick had finally had enough of Wheeler’s incessant agitation. The following morning, he ordered his full command to advance on Waynesboro, warning his men “to prepare for a fight; that he was going out to whip Wheeler.”

The 10th Ohio Cavalry led the assault, but almost immediately encountered a line of three barricades manned by dismounted Confederate cavalry. Wheeler looked to lure the Federals into a close fight the next morning, where he could negate any numerical advantage they enjoyed. The Confederates’ initial volley forced the Ohio men to fall back.

The Union cavalry deployed and advanced again, finding the first barricade abandoned. About three hundred yards farther, they came upon Wheeler’s main position, described as “a splendid defensive position with heavy rail barricade, with a swamp on one flank and the railway embankment on the other.” In short, Wheeler used the small detachment of men at the first barricade to draw Kilpatrick into a bottleneck from which the Federals could not easily escape once they were engaged there.

Kilpatrick ordered Colonel Smith D. Atkins’ 2nd Brigade to take the barricade. Atkins decided to pin down the enemy with severe fire while his mounted elements turned the flanks. He assigned Lt. Col. Matthew Van Buskirk’s 92nd Illinois Mounted Infantry to pin down Wheeler’s men at the barricade with the massed firepower of their Spencer repeating rifles, while the 9th Ohio Cavalry swept around Wheeler’s right flank and the 9th Michigan Cavalry and 10th Ohio Cavalry tried the left. While his men deployed, Kilpatrick decided to taunt his old West Point acquaintance, Wheeler. He grabbed his battle flag, stepped in front of the skirmish line, and called out, “Come on now, you cowardly scoundrel! Your [news] organs claim you have thrashed Kilpatrick every time. Here’s ‘Kil’ himself. Come out, and I’ll not leave enough of you to thrash a corporal’s guard!”

The 92nd Illinois laid down a heavy suppressing fire while the men of the 9th Ohio put spurs to their horses and dashed around Wheeler’s right flank. Colonel William D. Hamilton led the way. “I ordered my bugler to sound the charge,” Hamilton recalled. “The companies began to move in an awkward irregular line, looking back for me.” Hamilton waved his hat and cried, “‘Come on, boys.’ A shout went up all along the line, and the glitter of their sabers following the fire of the carbines showed the mettle of the men, when the charge was on.” One of Hamilton’s troopers said, “Away we went on the gallop, carbines firing, sabers flashing.”

While the 9th Ohio attacked the right, the 10th Ohio pounced on the other flank. Just before charging, 22-year-old Captain Samuel E. Norton, commanding the 10th’s Company D, called out, “Now for a name for our regiment.” The 10th Ohio dashed forward. “At the word of command 200 bright blades leaped from their scabbards, and with a yell away we flew like the sweeping cyclone, until the intervening space had been passed,” wrote one 10th Ohio trooper. “Moments seemed like hours.” Recalled another trooper of the 10th Ohio: “Suddenly a sheet of flames shot out from the…barricade…and as suddenly horses and riders were in the last agonies of death, blocking the way.” Another Buckeye watched a Confederate officer dashing up and down the enemy line of battle with his saber raised, calling on his brave men to defend against the enemy invaders. The Ohioans later learned that the officer was Fighting Joe himself. The 9th Michigan Cavalry joined the attack on the Confederate left.

While the flank attacks proceeded, the men of the 92nd Illinois charged the barricade, overrunning it as they “pumped their Spencers at the backs of the retreating rebel soldiers.” The color-bearer of the 92nd Illinois was shot down during the melee at the barricade, and a Confederate officer seized the flag. An Illinoisan grabbed the flagstaff and the two men wrestled for possession of the banner until the Illinoisan freed his revolver, aimed at the Confederate, and compelled him to surrender.

Wheeler “made several counter-charges to save his dismounted men and check our rapid advance,” Kilpatrick noted. At that moment, Kilpatrick committed his reserve, the 5th Ohio Cavalry, calling out, “Col. [Thomas T.] Heath, take your regiment; charge by column of fours down that road and give those fellows a start.” Kilpatrick apparently joined the Buckeye charge. “They rode over the rebel barricade, hewed men down and used their pistols in a close engagement.” Some 14th Corps infantrymen arrived just in time to witness this charge. “The charge by our cavalry across the open field was a most sublimely grand, never-to-be-forgotten scene,” recounted an Ohio soldier, “no words of the writer can describe or paint the picture.” An Indiana soldier watched as some of the Rebels “had to retreat across a large swamp about a mile ahead and the road was graded high and about wide enough for three or four men to ride abreast. They was in such a hurry they crowded each other off.”

Kilpatrick wasn’t aware that Wheeler had erected a third, stronger barricade just outside Waynesboro, on the banks of McIntosh Creek, and his men fell back and took position behind it. “Between us and Waynesboro was a valley, through which ran a small creek,” recalled an 8th Indiana Cavalry trooper. “On the north or opposite side of this creek the rebels had taken their stand, having their artillery well posted.” Kilpatrick moved his 1st Brigade into position to assault this artillery-supported barricade, only to realize that he could not flank Wheeler out of it, as the Southern commander’s “flanks [were] so far extended that it was useless to attempt to turn them. I therefore determined to break his center.”

From an Old ‘Friend’

Captain Samuel E. Norton of Company D, 10th Ohio Cavalry, was wounded while leading a charge during the December 4 fighting, hurt too badly to move. Kilpatrick sent Wheeler this note: General: For the memory of old associations, please let Corpl. M.D. Lacey, Tenth Ohio Cavalry, to remain to attend a wounded soldier, one for whom you should have every respect, for he is a very brave and true gentleman. Captain Norton was wounded today charging your barricades. Please show him such attention as is in your power, and at some future day you shall have the thanks of your old friend, J. Kilpatrick, U.S. Army.

Wheeler assured the Federal commander that Norton, a particular favorite of Kilpatrick’s, was being well cared for and resting comfortably. He then asked his fellow West Pointer to show the same mercy to the civilians of Georgia. But Norton’s wound proved mortal. He died a few days later.–E.J.W.

The 1st Brigade, commanded by the 3rd Kentucky Cavalry’s Colonel Eli H. Murray, advanced mounted. The 3rd assaulted the Confederate left, the 9th Pennsylvania Cavalry headed for the right flank, and the 8th Indiana Cavalry attacked the center dismounted, with the 2nd and 5th Kentucky Cavalry held in reserve, all supported by the 10th Wisconsin Battery. Because the 3rd Kentucky attacked first, it drew the full attention of Wheeler’s troopers, whose muzzles blazed. “No body of men ever stood fire more resolutely, not a man faltered,” noted the commander of the 3rd Kentucky. “At length, the enemy’s fire becoming fierce and many of their comrades falling around them, they disregarded the restraints of discipline and rushed, with wild shouts, upon the enemy in their front.” The 9th Pennsylvania then made a mounted charge on the Confederate right flank.

As the dismounted troopers of the 8th Indiana fired volley after volley at the center of Wheeler’s line, the Union horse artillery shelled it. At that moment, Murray committed the 2nd Kentucky, which drew sabers and charged the center of the barricade. They smashed through the Rebel line, and Wheeler’s position collapsed, his beaten troopers driven back into and then through Waynesboro. Wheeler admitted that his troopers “were so warmly pressed that it was with difficulty we succeeded in withdrawing.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]A victorious Kilpatrick relished the moment. He rushed “around like a child with a new toy,” saying: “I knew I could lick Wheeler!”[/quote]

Backed by at least one battery of horse artillery, Wheeler smartly and professionally re-formed his command on the north side of Brier Creek to defend the three bridges that crossed it. Atkins’ 2nd Brigade pursued the retreating Confederates right up to the creek, and the 5th Ohio Cavalry destroyed the railroad bridge before turning their attention to the two wagon overpasses on either side (Walker’s Bridge and Rae’s Bridge), which they proceeded to destroy while covered by the 5th Kentucky Cavalry. In town, meanwhile, 9th Pennsylvania troopers “amused themselves by examining the contents of the fine houses in town and making several bon fires of buildings, &c.”

A victorious Kilpatrick relished the moment. He rushed “around like a child with a new toy, saying: ‘I knew I could lick Wheeler! I can do it again!’” Kilpatrick and Baird then withdrew and bivouacked for the night. They continued their march south the next day.

Major James A. Connolly, serving on Sherman’s staff, held little regard for Kilpatrick and his troopers. He wrote in his diary: “So many cavalry in line in an open plain make a beautiful sight. But it is all show; there’s not much fight in them, though Kilpatrick’s men have behaved very handsomely today. They did all the fighting and whipped Wheeler soundly….But then Kilpatrick’s men had the moral support of two of our brigades that were formed in line right behind them and kept moving forward as they moved, so that our cavalry all the time knew that there was no chance of their being whipped.”

“This has been a regular field day,and we have had ‘lots of fun’ chasing Wheeler and his cavalry,” Connolly added. “Kilpatrick is full of fun and frolic and he was in excellent spirits all day….A cavalry fight is just about as much fun as a fox hunt; but, of course, in the midst of the fun somebody is getting hurt all the time. But it is by no means the serious work that infantry fighting is.”

The Confederates retreated after taking approximately 250 casualties in the vicious fight. Though Wheeler claimed he had inflicted 197 Federal casualties, Kilpatrick had in fact delivered him a thrashing. At the time, Wheeler also continued to believe he had prevented Kilpatrick from moving on Augusta, and that he had saved his beloved hometown, not realizing he had been fooled by the Federal commander’s adroit feint, which had also allowed Sherman’s main force to proceed to Savannah mostly unhindered.

In the engagements around Waynesboro, Wheeler was counting on his knowledge and understanding of Kilpatrick’s aggressive nature to entice his opponent into battle, figuring “Kilcavalry” would commit his entire force to the fight and could get trapped. Wheeler prepared three formidable defensive positions and executed his game plan—a delaying action—well. Kilpatrick triumphed with simultaneous attacks on the center and on both flanks on two separate occasions during the battle.

A little more than two months’ later, during the Carolinas Campaign, Wheeler and Kilpatrick dueled again in similar fashion at the February 11 Battle of Aiken, S.C. Wheeler got the upper hand on the field this time, forcing Atkins’ 2nd Brigade to withdraw and nearly capturing Kilpatrick in the process. But for Wheeler, it was ultimately a setback, as he had fallen victim to another feint by the Federal cavalry. Kilpatrick had again compelled Wheeler into thinking he was threatening Augusta, as Sherman’s army advanced on the South Carolina capital of Columbia.

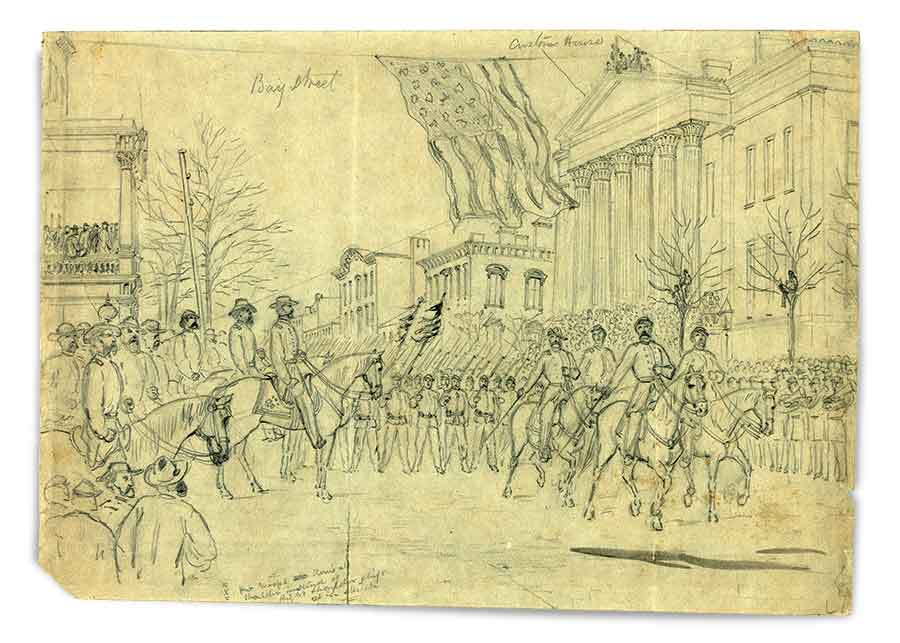

By working to steer Kilpatrick away from Augusta, Wheeler had allowed Sherman to reach Savannah nearly unhindered and capture the city on December 21, 1864. A week after the Battle of Aiken, Sherman captured Columbia without interference from Rebel cavalry.

Joe Wheeler’s obsession with defeating Judson Kilpatrick had far-reaching consequences for the Confederacy, undoubtedly hastening the South’s inevitable defeat.

Eric J. Wittenberg is an award-winning historian, speaker, and tour guide, and the author of several Civil War titles, including Out Flew the Sabres: The Battle of Brandy Station. A native of southeastern Pennsylvania, he has been hooked on the Civil War from the time of a third grade visit to Gettysburg.