U.S. Naval Academy history professor Mary A. DeCredico specializes in the Civil War era and the Confederacy. Her first book, Patriotism for Profit: Georgia’s Urban Entrepreneurs and the Confederate War Effort (University of North Carolina Press) received the Museum of the Confederacy’s Jefferson Davis Award for outstanding scholarship on the Confederacy. She has also written Mary Boykin Chesnut: A Confederate Woman’s Life (Rowman-Littlefield). In Confederate Citadel: Richmond and Its People at War (University Press of Kentucky, 2020, $50) she explores the surprising disaffection of Richmonders for Jefferson Davis and the national government even though the city was the capital of the Confederacy.

Richmond changed during the war from a quiet bastion of the aristocracy to a “sin city” full of moneygrubbers on the make. How did that happen?

There was a sense that if Richmond was the capital, it would not be given up and would be a safe haven. That attracted refugees. It’s not possible to say how much the population of Richmond grew during the war because no wartime census was taken. However, historians estimate that Richmond had a population of 37,000 in 1860 and by the end of the war it was close to 130,000. The city’s infrastructure, especially the police, could not accommodate such an influx. There were acute housing shortages, currency speculation, prostitution, and an increase in crime.

Upper- and middle-class women took jobs outside the home, correct? Why?

A lot of women had to go to work because their husbands were in the Army. What they did depended on their social class. The plum jobs, which often required political connections, were working for Confederate government agencies, such as the Treasury Department. For illiterate women or even children who had to work to support their families, the only option was taking a low-paying, dangerous job in the war industries. On March 13, 1863, there was a massive explosion on Brown’s Island, where a Confederate munitions laboratory employed girls even as young as 7 or 8. More than 60 girls died and many more were disfigured. Still, the day after the explosion, women and girls lined up to take the jobs of the dead and injured.

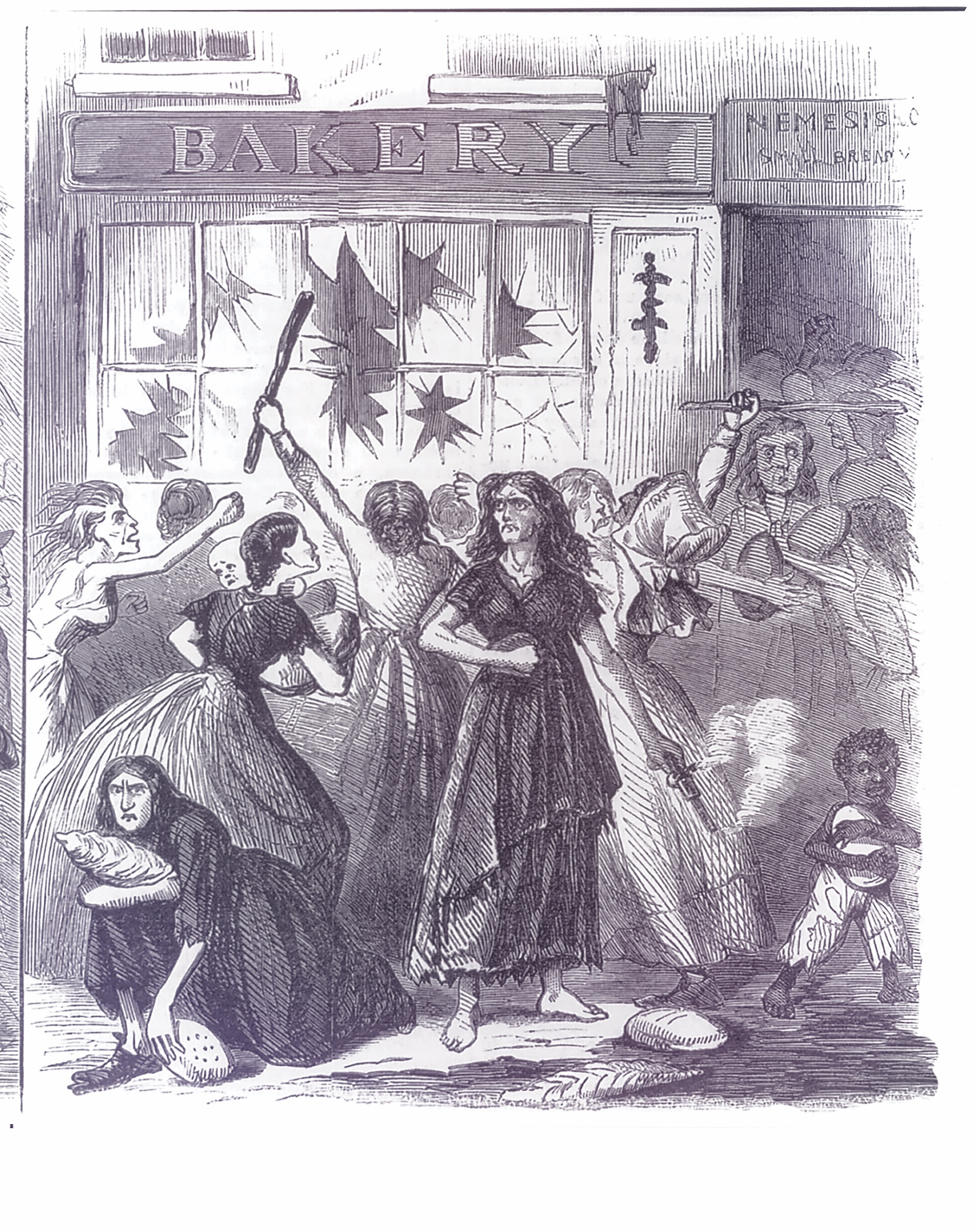

What caused the Bread Riot of April 2, 1863?

First of all, there were 22 measurable snowfalls in Richmond in the winter of 1862-63, which discouraged farmers from bringing their produce into the city markets. Although wages were going up, they did not keep pace with inflation. Then there was the Brown’s Island explosion. On April 2, women from the Oregon Hill neighborhood, which was home to most of the workers at the Tredegar Iron Works, marched on the governor’s mansion and then the business district. War Department clerk J.B. Jones asked one emaciated woman what was going on, and she replied, “We celebrate our right to live! We are starving!” What began as an orderly procession degenerated into a mob. Mayor Joseph Mayo, Governor John Letcher, and Jefferson Davis called on the women to disperse, arguing they were just helping the Yankees. A charity called Overseers of the Poor organized relief efforts. Those found “worthy”—in other words those who didn’t participate in the riot—were given tickets to a government store where they could buy food at below-market government rates. The “unworthy” poor, who were thought to have been in the mob, were out of luck. This was a dramatic departure from Richmond’s tradition of poor relief for all.

Discuss the situation in Richmond during the nine-month siege of Petersburg between June 1864 and April 1865.

The women of Richmond decided during November 1864 that the brave defenders of Richmond deserved a Christmas feast. But December rolled around and the organizers realized that they did not have enough food to feed the troops at Christmas. So they resolved to feed them New Year’s Day. The grand feast became two very small pieces of bread with a thin slice of ham. By this time, Lee’s army was hemorrhaging, with 100 men a day deserting the ranks. What I found fascinating was that the city, and the governor, tried to address this very thorny issue, but the Confederate government did nothing.

What occurred in Richmond when Robert E. Lee was forced to evacuate the lines around Petersburg after the Confederate loss at Five Forks on April 1, 1865?

The Confederate government ordered that Richmond be set on fire. My Southern midshipmen are always shocked when they learn that it was Jefferson Davis’ government that destroyed Richmond, not the Yankees. General Lee gave Lt. Gen. Richard Ewell, commander of the Department of Richmond, a very controversial order: If the Army of Northern Virginia was forced to evacuate Petersburg, you will torch the tobacco stored in Richmond’s warehouses. City officials begged Ewell not to do it. On April 2, after Grant broke Lee’s lines, the last elements of the Confederate Army marched out of Richmond and the tobacco warehouses were set alight. A wind suddenly picked up and the city descended into chaos and looting. The mob broke into government storehouses and found them packed to the roof with food. The City Council broke open the whiskey barrels and poured the liquor into the gutters. This is the scene playing out as the initial Union Army elements marched into the city. The first thing they had to do was put out the fires, which were engulfing huge swathes of the city and would burn for weeks. The Yankees were dumbstruck that the Confederates had set fire to their own capital.