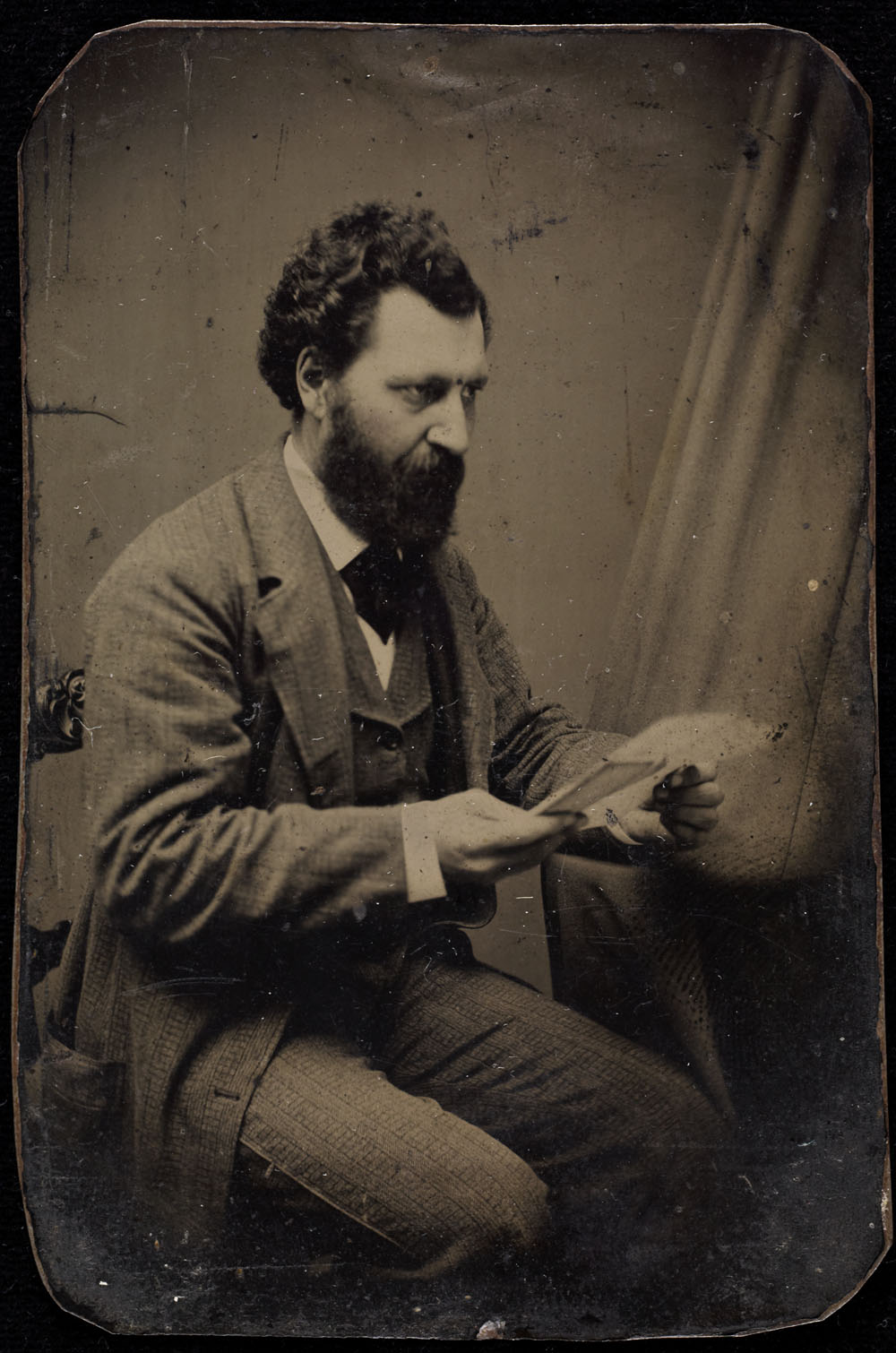

Louis Riel, President of the Comitié National des Métis, in 1875.

For the relatively young Dominion of Canada, no single year was more fraught with triumph and tragedy than 1885, a year that physically united and spiritually tested the country to the limit. The drama was played out mainly in what is now the western territory of Saskatchewan by a cast representing all the elements making up the Canadian identity: territorial and provincial governments, French, Scottish and Anglo-Canadians, Indians, soldiers, the railroad and, of course, the North West Mounted Police. At center state, however, was a unique race of Franco-Indian mixed-bloods called Métis and their charismatic leader, Louis Riel.

The Métis, common to the prairies northwest of the Great Lakes since the 1650s, are believed to have originated with members of Samuel de Champlain’s expedition, which founded Québec in 1608. As bronze differs from the copper and tin that comprise it, so the Métis seemed handsomely distinct from their white and Indian progenitors. Fiercely proud of their heritage, the Métis enjoyed a reputation for courage, honesty, hospitality and joie de vivre. Like their French fathers, they were devoutly Catholic, although they coexisted cordially with their neighbors of English or Scottish ancestry. They generally got along well with the Indians in the region, too, with the exception of the ever-aggressive Lakota.

The Lakota, however, were nowhere near as threatening to the Métis’ world as were the Anglo-Canadian settlers who began trickling into the Red River region during the 1860s. With whiskey as their main currency, they purchased tracts of land from Indians who had no concept of private ownership. The newcomers, who called themselves Canada Firsters, openly boasted of taking over the entire region from what they called the ‘indolent tribes,’ a reference as much to the Catholic Métis mixed-bloods as to the Indians.

Since 1812, the dominant political force between Lake Superior and the Rocky Mountains had been the Hudson’s Bay Company, whose trading policies largely gave the Métis what they wanted most — to be left alone. All that would change in 1867, however, with the Union of four British provinces, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario and Quebec, into the Dominion of Canada.

Feeling themselves threatened by the heavy-handed encroachment of the first wave of Canadian government surveyors, the Métis sought a spokesman to voice their concerns. They found him in the person of Louis Riel. Born in 1844, Louis David Riel was one-eighth Chippewa and the eldest of three sons and five daughters born to Louis and Julie Riel. Literacy was uncommon among the Métis, but young Louis showed such intellectual promise that he was sent to the seminary of the Gentlemen of St. Suplice in Montreal. There, Riel excelled in Latin, Greek, French, mathematics and the sciences. At age 19, he was studying the philosophers, writing poetry and considering a career in the priesthood. After the death of his father in 1864, however, Riel became moody, intolerant of criticism and somewhat disoriented as to what direction his life should take. When a love affair crumbled because the girl’s parents would not allow her to marry a Métis, an embittered Riel left the seminary without completing the term.

By October 1869, Riel had returned to the Red River territory, where he confronted government surveyors on behalf of Métis rights. As armed Canadians began arriving, Riel organized a Comitié National des Métis and a force of 400 men to block their entry into the territory, at the same time occupying Fort Garry, the Hudson’s Bay Company’s central establishment in the region, without a fight. From that position of strength, Riel and his confederates drafted a List of Rights, 18 demands that included protection of Métis land, religion and language, and a democratic voice in Canada’s new government.

While the demands were being negotiated with Ottawa, Riel called a convention to establish a provisional government. The convention, which represented whites as well as Métis, elected Riel president on February 9, 1870. At age 25, Riel did a remarkably competent job of keeping the peace in the Red River territory in spite of continued threats from the Canada Firsters. One of the latter, a roughneck Irishman from Ontario named Thomas Scott, violently challenged Riel’s authority and was shot to death by a firing squad for his trouble.

After much debate, Ottawa’s Parliament passed the Manitoba Act on July 15, 1870, creating a new province in the Red River region and acceding to all the Métis demands with the notable exception of amnesty for their leaders. An expedition of 1,200 troops, commanded by British Colonel Garnet Wolseley, embarked on a grueling 96-day march to restore Canadian authority in place of Riel’s provisional government.

When Wolseley arrived at Fort Garry on August 24, Riel was not on hand to personally relinquish his office. A white friend, James Stewart, had warned him that he would be in mortal danger at the hands of Canada Firsters who had elevated the late, loutish Thomas Scott to martyr status. As the soldiers approached, Riel fled to the United States.

Living mainly on the charity of friends and relatives, Riel became increasingly subject to mystical visions. The most significant came in December 1874, while he was visiting Mount Vernon, Va. There, Riel claimed that God had spoken to him in the form of a burning bush, commanding him to revive the Catholic Church by shifting its power base from Rome to the New World.

In 1875, the Ottawa government granted Riel a pardon for his rebellion and his part in the ‘murder’ of Scott, but only under condition that he remain in exile for five additional years. On March 9, 1882, he married an 18-year-old half-Cree women named Marguerite-Monet Bellehumeur. On March 16, 1883, they became U.S. citizens, and by 1884 Riel was teaching Indian children at St. Peter’s Jesuit Mission near Judith Basin, Montana.

Meanwhile, back north, the promises of the Manitoba Act were broken, Métis lands were stolen and the people displaced by Anglo-Canadian settlers. Most Métis moved west to the territory around the Saskatchewan River. There, they and their Indian cousins faced the next inevitable white encroachment with increased bitterness and hostility.

The years of 1883-1884 marked a winter of Indian discontent. Their land had been taken from them, the buffalo all but exterminated and they themselves were mainly confined to reservations. The government had pledged to see to their needs, but a recession in 1883 left it low on funds, and among the first budget cuts were rations for the non-voting Indians.

The Métis, meanwhile, were struggling to keep their land in Saskatchewan form the clutches of land speculators. Under the homestead law, the government regarded all Canadian land as Crown property until the individual registered his holdings and applied for a patent or deed. The process would take as long as three years, and the government was equally slow in surveying the land. Moreover, surveys were inflexibly done in square lots, rather than the long, narrow strips favored by the Métis in order to reach rivers and streams. Petitions for a prompter, more sensible approach to the matter were ignored in Ottawa, leading the Métis to a renewed resistance.

On June 4, 1884, Louis Riel was attending Sunday services at St. Peter’s Mission when he was informed that four men were waiting for him outside. Their spokesman was Gabriel Dumont, at age 47 a renowned horseman and buffalo hunter who was known as the ‘Prince of the Prairies.’ Dumont was illiterate, spoke no English and was no orator in French. He and his companions had ridden nearly 700 miles from the Saskatchewan Valley to formally enlist Riel in their cause. After much consideration, Riel agreed and, on June 27, he set out by cart with his wife and children.

Arriving in July in Batoche, a tiny village and ferry station on the east bank of the South Saskatchewan River, riel set up his headquarters and began addressing meeting sof Métis and white settlers, urging them to defend their interests. He also supervised the drafting of a new bill of rights, demanding provincial representation in Parliament, entitlement to existing riverfront lands with additional land concessions to the original settlers, reduction in tariffs, more liberal settlements of Indian claims and a new railroad to link Saskatchewan to ports on Hudson Bay.

Although Prime Minister John Macdonald acknowledged receipt of the petition on January 27, 1885, he did nothing more, maintaining that Parliament was discussing the matter. Losing patience, Riel announced on March 5, ‘We are going to take up arms for the glory of God, the honor of religion and for the salvation of our souls.’ On March 15, he told a gathering of supporters that, as a sign of approval, ‘God will draw His hand over the face of the sun.’ Soon after he spoke, the sky darkened — omen enough to convince his followers of the righteousness of their cause. What they didn’t know was that Riel had consulted an almanac and learned that there would be a partial eclipse of the gun that day.

On March 21, hoping to repeat his success of 1869, Riel formed another provisional government, to which he gave the Latin title Exovedate (‘those picked form the flock’), and appointed Gabriel Dumont commander of its army. Orgnaizing 400 cavalry, Dumont cut the telegraph line to Batoche, ransacked government stores and seized several hostages. At the same time, Riel sent an ultimatum to Major Leif Crozier at Fort Carlton, offering him and his North West Mounted Police safe conduct if they surrendered, but swearing, if they did not, to ‘commence without delay a war of extermination upon all those who have shown themselves hostile to our rights.’

On March 26, Crozier led 53 Mounted Police out of Fort Carlton and headed 13 miles east to retake the trading post at Duck Lake, which had been occupied by Métis and Indians under Dumont. Joining Crozier were 41 volunteers, a 7-pounder cannon and 20 horse-drawn sleighs. Forced by the soft spring snows to move in column along the trail, the Mounties noted with alarm that they were being encircled by snowshoe-clad Métis ad they approached Duck Lake.

Drawing one sled across the trail as a barricade, Crozier advanced with John McKay, a Scottish half-blood interpreter, to parlay under a white flag with Dumont’s brother Isodore an d an Indian named Assiyiwin. Perceiving the talk as a ploy to give the Métis more time to position themselves, McKay abruptly advised Crozier to call it off. Just then, Assiyiwin tried to grab the guide’s rifle. Drawing his revolver, McKay fired at the Indian. His bullet missed Assiyiwin, but struck Isodore Dumont fatally in the head. From then on, there was no hope for Riel’s uprising to be a bloodless affair — nor for the government in Ottawa to interpret it as anything other than an act of rebellion.

As both sides commenced shooting, Crozier’s men found themselves under fire from three sides. One volunteer reported firing at caps and Indian headdresses, only to discover that they were propped on sticks while their owners were sniping at him from somewhere else. A seemingly deserted cabin came alive with sharpshooters. After getting off three misaimed shots, Crozier’s cannon was put out of action when an excited gunner rammed home a shell ahead of its powder charge.

After half an hour, Crozier ordered a retreat. Ten police and volunteers lay dead, another 13 wounded. Five rebels had also died, and Gabriel Dumont, bloodied by a scalp wound, was among three such casualties as he ordered his men to annihilate the rest of Crozier’s retiring men. Riel countermanded the order, declaring, ‘There had been too much blood spilled already,’ and invited Crozier to recover his dead without fear of attack.

Barely an hour after Crozier’s detachment staggered back through the gates of Fort Carlton, a fresh force of 108 Mounted Police under Commissioner A.G. Irvine arrived, but Irvine prudently declared that Fort Carlton, more of a trading post than a defensive redoubt, was untenable, and on March 27 he ordered the 350 Mounties and civilians evacuated to the larger, stockaded settlement of Prince Albert. Dumont, well informed of the move, again proposed ambushing and slaughtering them, but again Riel forbade it.

While jubilation reigned at Batoche, news of the Métis victory at Duck Lake stirred anger and alarm in eastern Canada, as well as anxiety as to its effect on the Indians. Riel had, in fact, sent emissaries to several chiefs, imploring them to support his cause. Crowfoot, influential chief of the Blackfoot, saw no profit in it, and the majority of Indians concurred. Two exceptions were Big Bear, and old Cree chieftain who had refused to sign any treaties with the whites, and Crowfoot’s adopted son, Poundmaker, who had come to detest life on the reservation.

On March 28, the 500 settlers of Battleford, 100 miles west of Duck Lake, learned that 200 painted Cree warriors under Poundmaker were coming their way, and sought refuge in the Mounties’ barracks with its 43-man garrison. After demanding food, clothing and ammunition, the Indians began looting the Hudson’s Bay store and other buildings in town. The carnage spread to outlying farmhouses, which were sacked and burned. One settler who had tarried too long was murdered. Poundmaker then laid siege to the fort, but its defenders had stocked ample supplies of food and after three weeks the Indians gave up and moved on.

Meanwhile, 150 miles up the North Saskatchewan, a Cree war party led by Big Bear burst into the tiny hamlet of Frog Lake. Big Bear’s war chief, Wandering Spirit, shot the Indian agent and incited his braves to kill the others over Big Bear’s protests. Of the 13 white residents of Frog Lake, only three survived to be taken away as captives, while the Indian agent’s nephew, Henry Quinn, escaped to carry news of the massacre to Fort Pitt, 30 miles away.

Canadian armed forces rallied behind renewed patriotic fervor. Regular troops and reservists in Quebec, Ontario, Nova Scotia and Manitoba were joined by locally organized volunteers with names like Rocky Mountain Rangers and Moose Mountain Scouts. Altogether, a North West Field Force of 8,000 men, nine cannons and two newly acquired American Gatlin guns was assembled. Against that force, the Métis rebels could count on a maximum of 1,000 men, mostly armed with old shotguns and smoothbore hunting pieces. Of the 20,000 Indians in the region, no more than 400 had thrown their lot in with Riel, and the government moved to placate the still-loyal Blackfeet, Stoneys and Saulteaux with fresh provisions of flour, beef, tea and tobacco.

Still, there existed the problem of transporting all those troops to the troubled area. The transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railroad, which had been under construction since 1881, seemed to promise and answer, but a 250-mile stretch along the north shore of Lake Superior was still riddled with gaps where its builders struggled with the quaking rock ledges of the Canadian Shield. Until then, Prime Minister Macdonald and Montreal bankers had ignored the pleas of the near-bankrupt railroad for government loans. Now, seeing the North West Rebellion as a godsend, Canadian Pacific manager William Cornelius Van Horne offered to transport the troops to the prairie in 11 days, providing horse-drawn sleighs to shuttle the soldiers across the gaps, along with food and gallons of hot coffee at strategic points along the way.

Even with such accommodations, the trek along — and for a suspenseful eight-hour stretch, across — frozen Lake Superior was a harrowing ordeal, with snowblindness and at least one case of madness added to the more common occurrences of frostbite in temperatures that dropped as low as 35 degrees below zero. Nevertheless, by mid-April all units of the North West Field Force had reached their staging points along the railway beyond Winnipeg, and were ready to commence a three-pronged offensive into the heart of the Sakatchewan River territory.

On April 6, the main force under the expedition’s commander in chief, Maj. Gen. Frederick Dobson Middleton, started marching north from Qu’Appelle toward revel headquarters at Batoche. Farther west, Colonel William D. Otter was leading 543 men from Swift Current to Battleford, while a battalion under Maj. Gen. Thomas Bland Strange was to move from Calgary to the Feat Western prairies to pacify the area around Edmonton, then veer east in a pincer movement with Middleton to subdue the Cree near Fort Pitt.

A portly-white-bearded Sandhurst graduate, Middleton was a veteran of successful campaigns in India and New Zealand. Not renowned for swiftness of maneuver, he retained a faith in the massed infantry attack and the defensive power of the British square that was inappropriate for Canada, where mobility and concealment were of greater tactical advantage. Leaving most of his cavalry behind to guard supply depots and the railway, he marched his two columns of 800 troops 150 miles in three weeks.

The morning of April 24 found Middleton’s force encamped 20 miles from Batoche. A few miles away, in a small ravine at Fish Creek, 130 Métis and Indians lay in wait. Dumont had placed them in rifle pits concealed among the trees and brush, facing uphill to catch the advancing soldiers as they reached the brow of the hill, silhouetted against the sky.

In spite of the warning signs left by some young Métis horsemen who had been chasing stray cattle, Middleton marched his orderly ranks forward — right into the killing zone Dumont had prepared. As the Canadians arrived at the crest of the ravine, they were greeted by a hail of lead. Two artillery pieces were wheeled up, but could not be depressed enough to hit the Métis positions. After two bayonet rushes were thrown back, the Métis began signing ‘The Falcon’s Song,’ a traditional fighting air among the mixed-bloods, while another joined in on a flute. When Middleton called back his main force at nightfall, eight Métis were dead and 11 wounded, but the Canadians casualties came to 10 dead and 42 wounded.

Meanwhile, Otter’s relief force reached Battleford to the cheers of its populace. After a few days’ rest, he led 325 men, including 75 Mounties, along with two cannons and a Gatling gun, to the Cree camp at Cut Knife Creek to deal with Poundmaker on May 2. While the Canadian cannons fired on the teepees, however, Poundmaker’s war chief, Fineday, led his braves into the brush and within 20 minutes Indian muskets and arrows were pinning down Otters’ troops. Eventually the Canadians managed to fight their way back to Battleford, with eight men killed and 15 wounded. Fineday’s band had suffered five dead and a few wounded.

On May 5, Middleton was ready to resume his drive on Batoche, this time supported by the flat-bottomed riverboat Northcote, commandeered into service armed with a 7-pounder, a Gatling gun and 35 riflemen. The Hudson Bay supply vessel’s conversion to a gunboat had not gone unnoticed by Dumont’s scouts, however, and when it reached the narrow channel at the edge of town on May 9, gunfire erupted from both banks. As its crew poured on steam, Northcote‘s captain saw too late that the Métis had strung two heavy steel ferry cables across the river, several hundred feet apart. After Northcote passed under the first cable, both were lowered to entrap the vessel, but the Métis failed to bring them low enough to snag its hull. Instead, the second cable knocked the pilot house ajar, toppled the smokestack overboard and knocked over the mast and loading spars. While its crew put out a fire that had started in the debris, the river current carried Northcote around a bend to safety, but the farcical action had put the improvised gunboat out of the fight.

Later that morning, Middleton’s advance guard reached the outskirts of Batoche and his artillery began shelling the town. Middleton then ordered his infantry forward, only to be driven back once more by Métis firing from well concealed pits and trenches. At dusk, the Canadians withdrew behind a stockade of circled transport wagons, where they spent an uncomfortable night on cold rations under intermittent Métis fire and a large rocket improvised by Dumont to explode overhead at midnight, just to unnerve them further.

The next morning, a Sunday, saw Canadian skirmish lines re-established, but at no closer than 200 yards of the jeering Métis. While Riel visited his men, assuring them that God was on their side, the more pragmatic Dumont exhorted them to conserve their ammunition, which was running low.

On May 11, Toronto’s Royal Grenadiers advanced, bringing the Gatling gun up with them. At the ridge overlooking Batoche, two gun crews of the Winnipeg Field Battery began shelling the town, but were surprised by a number of Métis and Indians who had crept up along the ravine to within 20 yards. Captain Arthur L. Howard, operating the Gatling, ran his gun ahead of the battery and fired it into the charging rebels, mowing down some and putting the rest to flight. That marked the end of Canadian progress for the day and, for all the excitement, it left the redcoats no closer to victory as Middleton, twice bitten and thrice shy, resisted the pleas of his officers to resolve the issue with a bayonet charge.

Then, on May 12, an exasperated Ontarian took matters into his own hands. While Middleton was eating lunch, Lt. Col. Arthur Trefusis Heneage Williams led his Midland Battalion against the Métis trenches. Their cheers inspired the 90th Winnipeg Rifles and the Royal Grenadiers to join the charge. An enraged Middleton ordered his bugler to sound recall, but the troops ignored it and the general committed the rest of his men to their support.

The Métis fired at the oncoming Canadians with the last of their bullets, then reported to reloading with nails, pebbles and metal buttons. Most waited until the last minute to abandon their positions. When Dumont ordered a 93-year-old Métis named Joseph Ouellette to withdraw, the white-haired frontiersman replied, ‘Wait, I want to kill another Englishman.’ Moments later, the Canadians overran the trenches and fought their way into Batoche. One young soldier leaped into a trench to find himself sharing it with the corpse of an elderly Métis — Joseph Ouellette.

After being dislodged from the town, some Métis continued to snipe from trees along the river, but by 7 that evening it was over, as women and children emerged from the cellars and riverbank caves and the last of their men were rounded up. One souvenir-hunting redcoat discovered a shrine in a poplar grove, where Riel had conducted prayer meetings. It consisted of a cheap lithograph of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, mounted on cardboard, draped with a scrap of white muslin and nailed to a tree. The Canadian considered taking the sad little icon home, but then thought better of it and left it there.

The pivotal battle in Canada’s civil war was hardly comparable to Gettysburg in terms of casualties, but it was bad enough for the Canadians: Eight dead and 46 wounded among Middleton’s troops, 16 dead and 30 wounded among the Métis. The rebels’ wily leader, Dumont, refused to surrender and escaped the patrols sent after him to eventually reach the safety of Montana. The indomitable ‘Prince of the Prairies’ later became a star attraction at Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West show.

After hiding out in the woods for three days, Riel gave himself up to a party of mounted scouts. A week later, Riel was taken by steamer to Saskatoon, and then in a heavily guarded wagon caravan to the territorial capital of Regina, where he was placed in a Mounted Police guardhouse to await trial. With Batoche secured, Middleton marched on to relieve the town of Prince Albert, and then traveled to Battleford to receive the unconditional surrender of Poundmaker on May 26.

Pursued by the troops, Mounties and volunteers of General Strange’s column, Big Bear led a fighting withdrawal into the swampy northern wilderness, but after June 18 his starving Cree began turning themselves in at Fort Pitt. On July 2, Big Bear and his 12-year-old son surrendered at Fort Carlton.

About 80 whites and probably an equal number of Métis and Indians died in the North West Rebellion, which had cost the Canadian treasury $5 million. In Regina, 18 Métis were convicted of treason and sentenced to as much as seven years in prison. Eleven Indians were tried for murder at Battleford and sentenced to death. Three were pardoned, but the remaining eight, including Wandering Spirit, were hanged form a common scaffold. As a gesture of magnanimity, Big Bear and Poundmaker were spared the gallows and imprisoned. Both were freed after two years, but they were so physically ill and spiritually crushed by the experience of captivity that both died within six months of their release.

On July 28, 1885, the final drama was played out in a makeshift courtroom in Regina as the trial of Louis Riel began. In spite of the defense counsel’s pleas that his case be taken to a provincial court in the east, Riel came up before a part-time territorial magistrate and a jury of six white settlers. Accused of high treason, Riel responded firmly, ‘I have the honor to answer the court that I am not guilty,’ but witnesses and documents in his own handwriting alluding to a war of extermination against the whites caused his lawyers to abandon a direct defense and plead insanity. Riel, however, stated that he would prefer death on the gallows to ‘the animal life of an asylum.’

On the trial’s fifth day, the jurors deliberated for an hour and 20 minutes while Riel prayed softly in French and Latin. Then, foreman Francis Congrave solemnly announced, ‘We find the defendant guilty,’ but added, ‘Your Honor, I have been asked by my brother jurors to recommend the prisoner to the mercy of the crown.’

Unmoved, the judge sentenced Riel to hang on September 18, but his execution was repeatedly stayed as his lawyers appealed unsuccessfully to higher courts in Ottawa and London, and bitter controversy raged in editorial columns all over Canada. English Protestants branded Riel a madman and the most heinous traitor in Canadian history, while many French Canadians considered him the well-intentioned victim of lifelong injustice. Prime Minister Macdonald made no secret of his own opinion: ‘He shall hang though every dog in Quebec bark in his favor.’

At Craigellachie on November 7, 1885, a last iron spike was driven to complete the transcontinental Canadian Pacific Railroad — a watershed event made possible by government financial aid in recognition of the railroad’s role in transporting troops to suppress Riel’s revolt.

Nine days later, Riel, his last appeal having been denied, carried a small crucifix as he took his final walk to the scaffold in Regina. While a white hood was placed over his head and the noose was adjusted, he joined a priest in the Lord’s Prayer, his final words before taking the 9-foot plunge to eternity being ‘Lead us not into temptation, but deliver us…’ Canada had extracted her final sacrifice for nationhood. WW

This article was first published in the June 1991 Wild West. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!