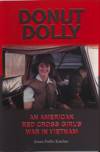

Donut Dolly: An American Red Cross Girl’s War in Vietnam, by Joann Puffer Kotcher, University of North Texas Press, 2011

Donut Dolly: An American Red Cross Girl’s War in Vietnam, by Joann Puffer Kotcher, University of North Texas Press, 2011

There were 627 young women who served in the American Red Cross Supplemental Recreation Activities Overseas program during the Vietnam War. Joann Puffer, a University of Michigan grad with a mathematics degree, became number 45 in May 1966. She was part of the vanguard of women, dubbed Donut Dollies, formally allowed to venture into combat zones.

Forty years after her Vietnam adventures, Joann Puffer Kotcher has written Donut Dolly, An American Red Cross Girl’s War in Vietnam, based largely on her personal journal and subsequent interviews.

While Kotcher dishes up an entertaining, honest and insightful view into the day-to-day life of a Donut Dolly, she makes a strong case for the impact that the small cadre of women in Vietnam had on the arc of women’s equality in the armed forces. The Dollies demonstrated the ability of women to go into dangerous situations in the field. As Kotcher notes, during World War II, women played an important role in a wide range of military and civilian jobs, but in the military their contributions did not develop into advancement of opportunity. That was not the case after Vietnam, and Kotcher claims, “The Red Cross girls’ success opened up opportunities for military women.”

Beyond recognizing the Dollies’ societal impacts, the strength of Kotcher’s memoir lies in its rare and detailed account of the life of one of these young women in Vietnam. During her tour, Kotcher went into combat zones in the Central Highlands, the Mekong Delta and even along the Cambodian border—and has a number of harrowing tales to prove it. The lessons she learned in these experiences are largely the same that soldiers encounter: “One of the first things I had to learn, as I sat in a bunker while artillery shells flew over my head, was how to fight fear and worry, how not to feel. Otherwise I couldn’t function. I might as well pack it up and go home.”

The fear and uncertainty that Kotcher describes are among the many experiences these women shared with the soldiers they were there to serve—a fact that is often lost in the Donut Dollies’ stories. Just like the GIs, Kotcher admits that “the closer I came to leaving Vietnam, the more impatient I became. I wanted to go home. I counted down the last 30 days, because everyone else did. It was the worst thing I could have done. The days dragged. They felt longer than they should have. Thirty days were forever.”

Kotcher’s Donut Dolly is a welcome and worthy addition to our understanding of the Vietnam War experience.

R.V. Lee