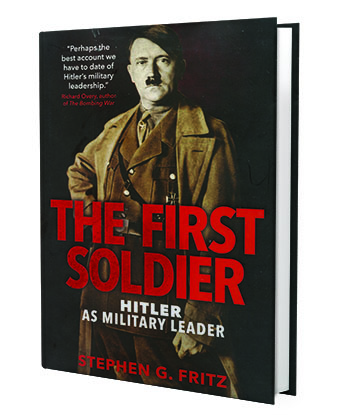

By Stephen G. Fritz. 459 pp. Yale University Press, 2018. $30.

HE ROSE FROM HUMBLE ORIGINS to supreme power, tried and failed to conquer the world, and killed millions. Yet even today some refuse to take Adolf Hitler seriously. The man called the Führer is still a caricature in many histories of World War II: a carpet-chewing madman frothing at the mouth, a jumped-up corporal issuing inane orders to his polished, professional commanders, a bumbling amateur who lost a war that Germany could have won.

Respected scholar Stephen G. Fritz is having none of it in The First Soldier. While offering zero justification for anything Hitler said, planned, or did, Fritz demolishes the “Hitler was an idiot” school of World War II history. Hitler had many strengths as a military commander, Fritz notes: openness to new ideas (especially those of mechanized warfare, as in the 1940 campaign), strength of will, and a concept of strategy that ranged well above that of his commanders.

Fritz also notes where the notion of Hitler’s bumbling came from in the first place: the German officer corps, seeking an excuse for its own complicity in the war’s aftermath. Trying to explain away their second lost war within a generation, German military leaders had a perfect fall guy, and they went after the dictator with a will in their widely read memoirs. As the most hated man of the 20th century, Hitler was unlikely to find many defenders—and he didn’t. The fact that the officers themselves had helped bring the dictator to power, supported his launch of the war, and slavishly obeyed his orders to the end were all inconvenient truths, conveniently omitted.

Like most military commanders since Napoleon, Hitler believed in going on the offensive whenever possible and in mounting a tenacious defense when necessary. He launched a war when he thought he enjoyed a strategic advantage and then hung on grimly when things turned south. He often failed, not because he was a fanatic, but because he was indecisive and could not make clean choices between clashing courses of action proposed by his officers. In all this, we read echoes of the great and not-so-great commanders of the past, present, and future.

Fritz’s most interesting insight is that the real German problem was not Hitler as military leader, but Hitler as political supremo. All the operational prowess in the world could not make up for Germany’s flawed political aims: conquest of a great empire, enslavement of subject races, and racial purification. Hitler the commander failed to prosecute the senseless war dreamed up by Hitler the Nazi Führer—but anyone would have. In the end, Fritz notes, Hitler’s vision of “absolute dominance” inevitably gave rise to “absolute resistance.”

Wise words from a wise book, one that offers us a historical portrait of the dictator, and not a caricature. —Robert M. Citino writes this magazine’s “Fire for Effect” column and is the National WWII Museum’s Samuel Zemurry Stone senior historian.

This review was originally published in the February 2019 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.