The Battle of Second Bull Run, or Manassas, is too often overlooked. The fight that took place on the plains of Manassas Aug. 28-30, 1862, literally on ground sprinkled with the washed-out graves of the fallen from the war’s first major battle (fought on July 21, 1861), is frequently cast as something only that led to the ensuing Antietam Campaign.

It was much more than that, though. The Second Battle of Manassas and the campaign that led to it are high drama of the first rate. They show, among other things, the Army of Northern Virginia shift from being a home protection force to one that was capable of undertaking a complex campaign and taking the war north.

No one has done a better job, and no one may ever do a better job, of laying out that campaign and its significance that John J. Hennessy did in his wonderful 1993 release, “Return to Bull Run: The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas.” Hennessy skillfully explains how Gen. Robert E. Lee shifted his army off the peninsula east of Richmond, swung it in an arc to the northwest, then cut east to imperil Washington, D.C., and precipitate the Battle of Second Manassas.

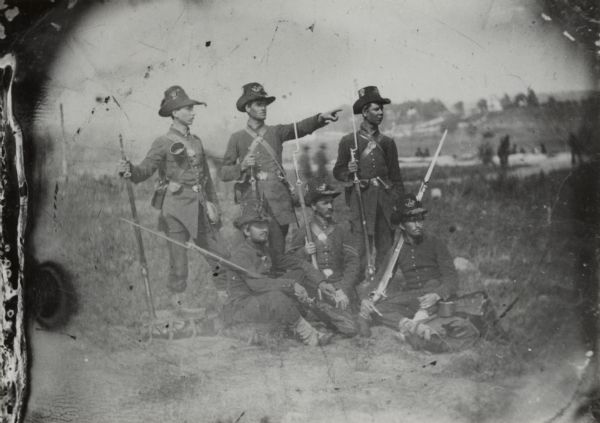

This is a different story of the Eastern Theater, pitting the Army of Northern Virginia not primarily against the Army of the Potomac but against Maj. Gen. John Pope’s Army of Virginia. While that Union army went down to defeat at Second Manassas, the blame didn’t lie with the mettle of its troops. Familiar names like those of Gettysburg hero John Buford came into the limelight, and the 4th Brigade of Pope’s 3rd Corps acquitted itself well during the battle. That brigade consisted of the 19th Indiana and the 2nd, 6th and 7th Wisconsin. You might know it better as the Iron Brigade.

Return to Bull Run

The Campaign and Battle of Second Manassas

by John J. Hennessy, Simon and Schuster, 1993

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.

On the Confederate side, Hennessy describes how Lee took tighter control of his army, winnowing out some less-competent commanders and trusting in two of his ablest generals, James Longstreet and Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, to lead the complex offensive movement. Jackson, in particular, shone and redeemed himself after comparative lethargy during some of the Peninsula fights.

Stonewall struck west with authority, defeating a portion of Pope’s army at the preliminary Battle of Cedar Mountain on Aug. 10, and then continuing to befuddle his opponents and capture the bounty at Manassas Junction on Aug. 27. That capture forced Pope to fall back from the Rappahannock River and precipitated Second Manassas. Lee would again use that successful recipe, split his forces and hit on the flank to cook up a victory at Chancellorsville.

Hennessy lays out the fight itself in clear, exciting prose. The standoff at Brawner’s Farm, the desperate fighting at the Deep Cut of an unfinished railroad, and Longstreet’s hammer blow on Chinn Ridge on the battle’s final day are told as gripping stories.

And when the battle was over and defeated U.S. troops once again made for the safety of D.C.’s forts, a gloom settled over Abraham Lincoln’s administration, while gleeful Confederates exulted and prepared for their next move.

Hennessy, who recently retired after years of working at Civil War Battlefields for the National Park Service, masterfully tells this tale, weaving in the voices of common soldiers as well as those of commanders, and deftly explaining complicated strategy and political machinations that took place in the late summer of 1862. Clear, copious maps convey the pitch and sway of battle. This, frankly, is one of the best campaign-and-battle narratives I have ever read.

And you know what? When you’re done reading this book, you just might think, as I do, that Second Manassas, not Chancellorsville, was Lee’s greatest victory.