The wreckage site of a World War II U.S. Navy escort carrier was identified Monday by the Naval History and Heritage Command’s Underwater Archaeology branch, bringing a semblance of closure to the crew of a ship that dipped beneath the waves 78 years ago.

The USS Ommaney Bay (CVE 79) was transiting the Sulu Sea near the Philippines on the evening of Jan. 4, 1945, when it came under attack by a twin-engine aircraft flown by a Japanese kamikaze pilot.

The ship’s skipper, Capt. Howard L. Young, had just opted to install extra guards on deck as an extra precautionary measure against such attacks — but the effort proved futile.

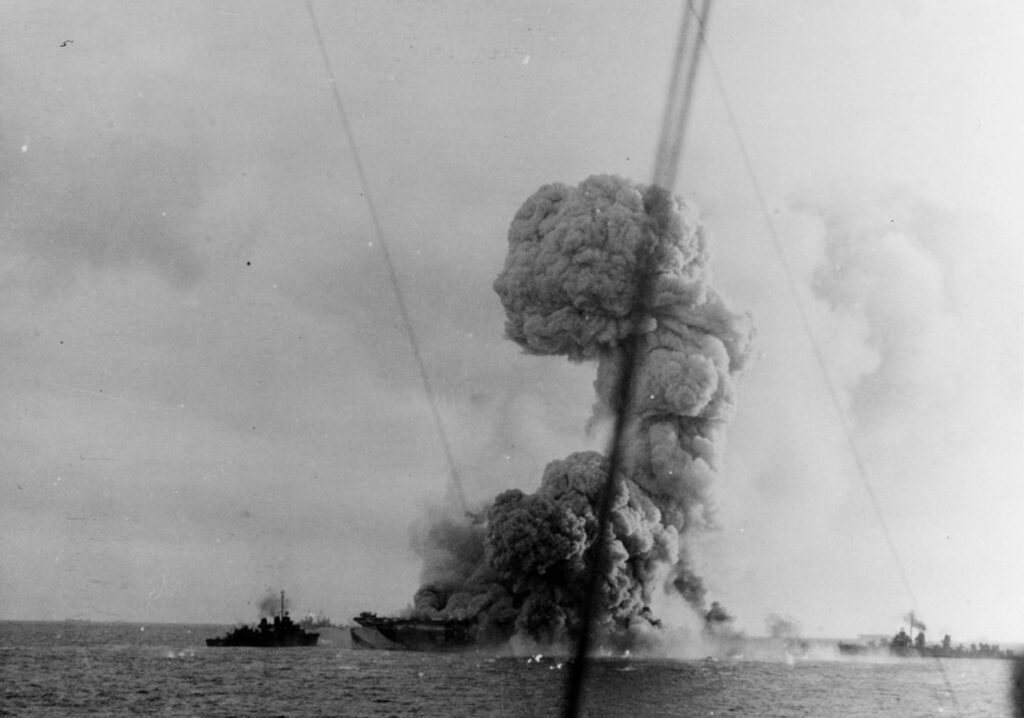

The incoming aircraft, which no sailors spotted until it was too late, slammed into the Casablanca-class escort carrier’s starboard side, erupting its two attached bombs and igniting a conflagration on the ship’s flight deck, where a slew of aircraft that had not yet been degassed were assembled.

“The second bomb exploded close to the starboard side after rupturing the fire main on the second deck and passing through the hanger deck,” the NHHC release stated.

Other ships rushed to pull alongside the “Big O” and assist with the fires but were quickly beaten back by the searing heat. As the gasoline- and bomb-fueled inferno spread, an even more dire issue arose — the ship’s torpedo warheads could explode.

At 5:45 p.m., 45 minutes after the plane tore into the carrier, the abandon ship order was issued by Adm. Jesse B. Oldendorft, the top officer aboard the adjacent Fletcher-class destroyer USS Burns.

Joe Cooper, a sailor aboard the Ommaney Bay, recalled desperately awaiting rescue in the water after abandoning ship.

“There was sharks. Looked like men were climbing on each other’s shoulders to get out of the water,” Cooper told the Veterans History Museum of the Carolinas. “I remembered from Guadalcanal, we saw a submarine’s periscope. We fired a torpedo. I run back there and saw oil slicks. It was a cargo ship and sunk it. It was our first submarine. I’d seen men get pulled under by sharks and ate up at Guadalcanal. After Guadalcanal, they told us, ‘If you ever hit the water, don’t kick or nothing, because the sharks will come after you.’

“In the water, I stayed still and a few sharks just went by me. No ships came to support us because the light carrier Princeton had been damaged when it went alongside the Birmingham when it was bombed, so they stayed away from us. So they let us burn.”

Around 8 p.m. the USS Burns fired a single torpedo at the unsalvageable escort carrier, sending the hulking, broiling ship below the surface for good. Of her 800-strong crew, 95 were lost.

A crew working alongside NHHC personnel located the ship Monday using “a combination of survey information provided by the Sea Scan Survey team and video footage provided by the DPT Scuba dive team,” according to the release. “This information was correlated with location data for the wreck site” gathered in 2019.

“Ommaney Bay is the final resting place of American Sailors who made the ultimate sacrifice in defense of their country,” retired admiral and NHHC Director Samuel J. Cox said in a release announcing the location of the wreckage. “This discovery allows the families of those lost some amount of closure and gives us all another chance to remember and honor their service to our nation.”