Beads of sweat streamed down the dirt-smeared face of Cpl. Tommy “Hatch” Hatcher of 1st Platoon, Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, 3rd Marine Division. The hill he had just climbed was steep, and his company had ascended 1,800 feet of its nearly 2,000-foot height. Hatch’s 10-pound armor vest didn’t help, nor did the 45-pound M60 machine gun and a belt of ammo he lugged. About 50 yards from the top, Charlie Company Marines awaited orders from battalion commander Col. John “Blackie” Cahill, walking the hillside with them.

The Marines were told a North Vietnamese Army squad, occupying a bunker complex on the ridgetop, had Alpha Company pinned down. Charlie would move to the eastern/southeastern ridge to relieve pressure on Alpha and allow it to withdraw its 10 dead and 20 wounded. Delta Company would aid from the northwest. After several excruciating minutes, the radio transmitted the orders to Charlie Company: “Move out your 1st Platoon.” It was 2:30 p.m. on April 16, 1968.

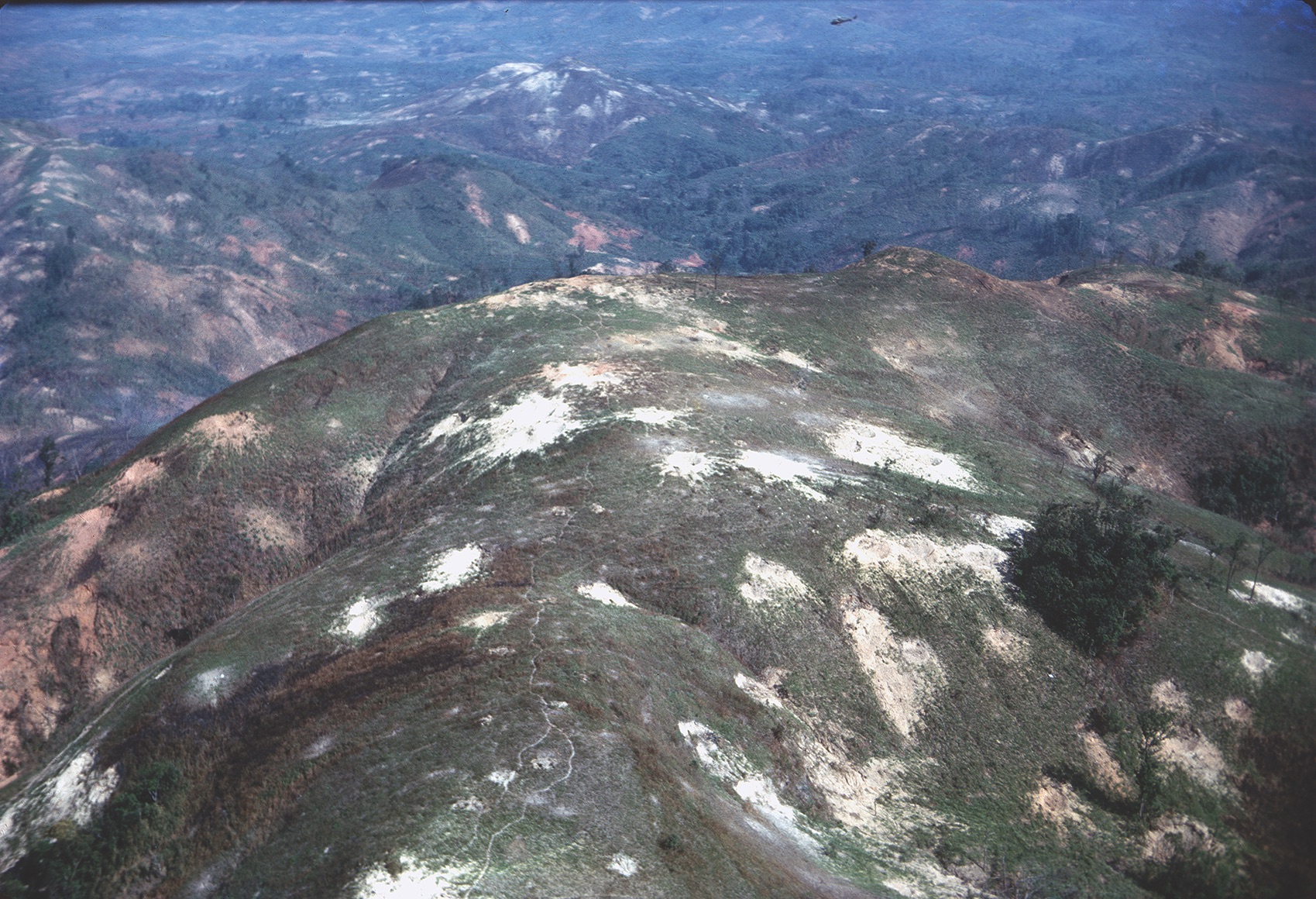

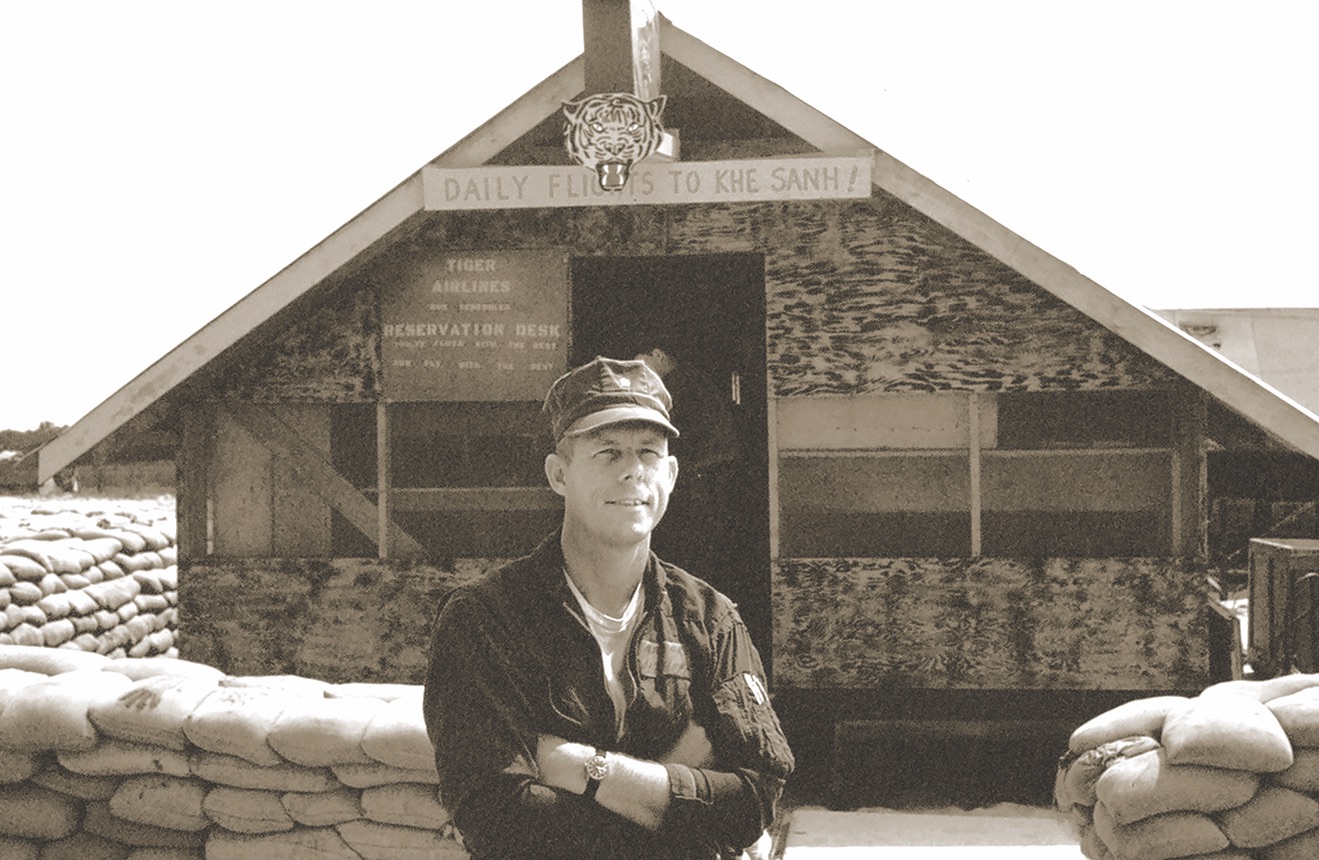

That day the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, which had adopted “The Walking Dead” as its nickname, was on Hill 600 (named for its height in meters), about 3 miles west of the Marine base at Khe Sanh in northwestern South Vietnam near the Laotian border. The battlefield around Khe Sanh was in transition in mid-April 1968. An NVA siege of the base that had begun on Jan. 21 was broken April 8 by a relief force of infantry troops from the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) during Operation Pegasus. Now Marine units from Khe Sanh were scouring the surrounding hills for NVA troops positioned in the area to direct artillery and rocket strikes launched from Laos. During the past week the Marines had largely found squad-sized units, and many assumed the NVA had largely evacuated the area.

On April 16, air cavalry scouts radioed an Army unit on a nearby hill and reported that the NVA was repopulating the hills around Khe Sanh. All elements of the NVA’s 66th Regiment, 304th Division, had moved back into an area near Highway 9 and Lang Vei. This vital intelligence, however, was not passed along to Marine commanders, and thus the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, soon found itself engaged by a strong NVA force on Hill 600, about a mile southwest of Hill 689, the battalion’s operations center at the time.

Hatcher could hear Alpha Company’s fierce battle on the hill above him, echoed in the sounds of M16 and AK-47 rifles, grenades and mortar fire. The M60-wielding corporal, with fellow Cpl. Eldon Kilpatrick at his side, moved warily toward the action. They were just several steps shy of the hilltop when a well-camouflaged NVA soldier popped out of a small, hidden “spider hole” and lobbed a wooden-handled grenade at their feet.

The explosion knocked both Marines into the air. As the dust settled, Hatcher got to his knees, ears ringing but otherwise unhurt. He grabbed his helmet, finding it peppered with holes. Kilpatrick was close by. As bullets zipped through the air, the two Marines pressed ahead, and a few feet later a mortar round dropped both of them to the ground, seriously wounded.

Meanwhile, Sgt. Bill Rider’s squad from Charlie Company’s 2nd Platoon was moving around the hill’s western flank. Along the rim, numerous North Vietnamese regulars were running up the hill toward the battle. Instantly, Rider knew the 1st Battalion was not up against some small “squad” of NVA. It was facing a heavily reinforced company (possibly even a battalion) of well-equipped enemy soldiers who slipped in from Laos. The Marines were in serious danger of being overrun.

As the sniper fire intensified, Rider and his squad bounded into a series of craters created by B-52 bombers. In a position on the edge of a huge crater 20 yards away, 18-year-old Pfc. George Panykaninec of 2nd Platoon popped up and fired an M16 burst at an advancing enemy soldier. In reckless excitement, he poked his head up again, boasting to his squad mates, “I got him!” Just then a sniper’s bullet hit the private in the head with what appeared to be a certain “kill shot.” That was the last the squad ever saw of Panykaninec.

One by one, Rider’s squad members were picked off as the day dragged on into twilight. Even before casualties began to mount for Charlie’s Company’s 2nd Platoon, Cpl. Hubert Hunnicutt, a lay minister nicknamed “Preacher,” thought, “This is madness.”

The platoon advanced into the deadly NVA crossfire. Despite the grass cover on the crest of the hill, the Marines were only able to move a few yards at a time, from crater to crater.

About 5 p.m., as Hunnicutt tried to crawl out of a crater, a bullet hit his left arm. He yelled back to his lines: “C Company. I need some help.” Lance Cpl. Ross Kasminoff, one of six in a nearby bomb crater, called back, “Hey, Preacher, can you run back here?”

Hunnicutt responded, “Negative, I’ve got two wounded up here with me.”

“We’ll lay down a base of fire,” Kasminoff replied, “and you run back here. We’ll get the wounded.

While the Marines continued their fire, NVA mortarmen making adjustments in their shelling were getting closer to Hunnicutt’s crater. Cpl. Henry Castaneda called out, “Hey, Preacher, get out of the crater!!” Two mortar rounds dropped into the crater area. After a few tense minutes, Hunnicutt announced, “I’m hit again.”

“We’ll come get you, Hunnicutt,” Castaneda said. Moments later, the enemy lobbed grenades onto Hunnicutt’s position. As the dust settled, Hunnicutt thought, “I’m walking dead, and my guys aren’t going to stop trying to get me until they all get killed.” He decided to keep quiet. Even as his comrades called out, “Preacher…Preacher!” Hunnicutt remained silent. Surely, his fellow Marines assumed, Hunnicutt was dead.

At 5:45 p.m., battalion commander Cahill, on a makeshift medevac landing zone down-slope on Hill 600, spoke with Capt. Charles Hartzell, the battalion operations officer, and Maj. Joseph Donnelly, the executive officer, at the operations center on Hill 689.

“Get everyone off the hill as fast as you can and bring the wounded with you,” Cahill said. “Don’t attempt to extract the killed and [thereby] take additional casualties. We will get them later. Get everyone back to Hill 689.”

The action to relieve the pinned-down Alpha Company soldiers resulted in 19 Marines killed, 36 wounded and 15 still unaccounted for—missing and presumed dead, but possibly alive.

About 6:30 a.m. on April 17, Hunnicutt, still trapped on Hill 600, called for help. Across the valley on Hill 689, other Marines heard and recognized his voice. A two-squad patrol with four stretcher bearers from Charlie Company’s 3rd Platoon was sent to the base of Hill 600. About 8:30 a.m. Hunnicutt shouted, “C Company!”

From a few hundred yards away came the reply: “Where are you, Preacher?”

“I’m on top of the hill… come get me,” Hunnicutt yelled. He fired off two rounds to mark his location. As the team members cautiously tried to pick their way up the hill, they shouted, “Preacher…Preacher.” Hunnicutt, who couldn’t hear the team calling from below, didn’t respond. He was again written off for dead.

Marine Capt. Peter Erenfeld piloted his Cessna L-19 Bird Dog aerial observer plane—the eyes in the sky for the infantry—over Hill 600 about midday. He was looking for potential enemy targets and signs of a Marine whose name he heard over the radio that morning—Hunnicutt. Erenfeld made a low, slow turn over the ridge as the devastation of the previous day’s battle came into view. Intermixed among hundreds of spider holes, bunkers and B-52 bomb craters were the bodies of dead Marines.

As the Bird Dog pilot continued to make his turn, he noticed movement below. Erenfeld slid open a side window and craned his neck to get a better look. In a bomb crater was a lone figure in a Marine flak jacket and helmet. The man was waving his foot in the air. Erenfeld called the 1st Battalion air officer, Capt. Don Engel. It was now 1:30 p.m.

Battalion staff officers Hartzell and Donnelly told Cahill they were strongly opposed to sending any more Marines up the hill to rescue the one seen by Erenfeld. The man in the crater, whose identity wasn’t confirmed at this point, was “alive because the gooks want him alive and is probably a stakeout for snipers,” Hartzell said. “Colonel, we’ll lose more killed and wounded if we go up there.” Donnelly suggested a plan: “We need to blow the hell out of the flanks, right side and the front and get him out by recon extract.”

Cahill agreed and requested a helicopter operation to retrieve the Marine on the hill. He wanted multiple UH-1 “Huey” gunships, two CH-46 Sea Knight transport helicopters hauling Marines, and chase copters (backups in case the lead helicopters crashed), accompanied by multiple A-4E Skyhawk and F-4 Phantom fighters flying nearby. The operation got only two Sea Knights and two Huey gunships.

Maj. David Althoff of Marine Medium Helicopter Squadron 262, running resupply missions around Khe Sanh in a Sea Knight with Col. John Hansen as co-pilot, was scanning the radio when he heard a call from Khe Sahn for assistance with a rescue operation. Althoff turned to Hansen: “Well colonel, I think things are about to get really exciting.” Althoff’s CH-46, his wingman’s helo piloted by Capt. Bill Barba, and two Huey gunships turned west toward the imperiled Marines.

Althoff landed on Hill 689. Rider boarded the Sea Knight with a rifle team of three other Marines he had quickly pulled together. He was the only one who had been up on the hill the day before and knew firsthand that they were flying into a hornet’s nest.

Soon Althoff was circling Hill 600. He had reached it so quickly that the Marine gunships did not have time to blast the NVA below before the Sea Knight circled once and then descended. Both of the helicopter’s side gunners blanketed the landscape with M60 rounds. Althoff hovered over a spot about 50 yards from the Marine being rescued—who happened to be Panykaninec, not Hunnicutt, a confusion that wouldn’t be cleared up until well after the rescue.

As the copter’s back ramp lowered—crushing an NVA soldier underneath—machine gun rounds zipped through the air. Rider stood at the base of the ramp as lance corporals Steve Haddad and Roger Rautio exited firing into space. All anyone could see was the dust kicked up by the rotor wash and the muzzle flashes popping out of that maelstrom.

The ping of rounds hitting the aircraft caused Rider to look up. He saw hydraulic fluid streaming down the side. One minute after touchdown, Althoff bellowed to his crew chief: “Get them back in here…we have to leave…NOW!” As Rider’s team piled back on, Althoff fought to get the dying helicopter airborne.

Two 60 mm mortar rounds exploded nearby. With the Sea Knight leaking aviation fuel as well as hydraulic fluid, the crew struggled to get it just high enough to drift and fall about 1,000 yards away, landing hard at the base of Hill 689. Afraid the helicopter was going to explode, everyone quickly bailed. No one was hurt, but they hadn’t picked up any stranded Marines either.

Col. Bruce Meyers, commanding officer of the 26th Marine Regiment, was at Khe Sanh monitoring the rescue mission over the radio. He conferred with 3rd Marine Division commander Maj. Gen. Rathvon Tompkins, and they suspended the air rescue attempts, deeming them too risky and opting instead to organize more deliberate recovery operations after extensive bombardment of the hill.

Army helicopter pilot Capt. Barry Brown was flying near Hill 600 when he heard the radio chatter and asked Marine air officer Engel if he could provide any assistance. Brown was the leader of 2nd Platoon, B Battery, 2nd Battalion, 20th Field Artillery Regiment (Aerial Rocket Artillery), in the 1st Cavalry Division. The battalion’s call sign was Blue Max. Each Blue Max Huey had four dozen 2.75-inch rockets with 10-pound warheads. The choppers’ crews were highly experienced in working dangerous missions with Army ground units.

Engel briefed Brown: CH-46 shot down. NVA laying in ambush. Marine possibly being used as bait. He emphasized that the Blue Max was the last hope for the dying Marine. And time was running out. Night was coming.

Brown had three Blue Max sections (six helicopters) at his disposal. The lead aircraft, Blue Max 48 with him as pilot and Warrant Officer John Miller as co-pilot, would make two preliminary runs. On the first run, Brown would fire half his rockets on the north side of the Marine’s crater, marking its location. On the next, he would fire the remaining rockets on the south side. Each salvo would be delivered within 20 yards of the Marine’s position to kill any NVA lying in wait.

Brown would then make a final run and land at the crater. After the landing his crew chief, Spc. 5 Joe Lynch, would jump out to extract the Marine. The other two Blue Max sections would provide cover. Blue Max 49 section, headed by Capt. Charlie Dorr, would expend all its rockets on the crater’s north side. Blue Max 47 section, led by 1st Lt. Jerry Bijold, would hit south. In total, 288 rockets and 20,000 machine gun rounds.

Brown made his first rocket-firing run at 6:25 p.m. On the second run, he banked sharply and came around with the other five Blue Max helicopters in file behind him. Some 200 yards from the intended landing area, Brown’s Blue Max rockets exploded on the hill. Within feet of the landing zone, Brown realized that the hillslope’s incline was too steep to land, but he would have to hover close enough to the ground for Lynch to get the Marine up into the helicopter.

As the Huey hovered, Lynch jumped off and co-pilot Miller sprang to the back to fire the already-hot machine gun. Dirt and flame combined as aerial rockets exploded all around Blue Max 48. Despite the continuous rocket fire, NVA troops scrambled around the landing zone. Miller swung the gun toward each target who showed himself.

Rotor wash enveloped Lynch in blinding dust, but he reached the crater within seconds and grabbed at Panykaninec. The Marine private, still clutching his K-Bar combat knife, instinctively swung it at Lynch, who deflected the blow and snatched the blade.

Lynch then began the exhausting task of pulling the 165-pound man out of a hole the size of a swimming pool. But with an assist from coursing adrenaline, he was able to get Panykaninec into the Huey.

Without waiting for anyone to strap in, Brown turned his helicopter 180 degrees, dove it off the hill and raced at maximum speed toward Khe Sanh. Within minutes, Panykaninec was being carried on a stretcher to waiting surgeons at the base. It wouldn’t be known for a few more hours, however, that he was not Hunnicutt.

Fifteen minutes after Panykaninec was pulled out the crater, six flights of Skyhawks and Phantoms bombed the top of hill. When the bombing ceased, Bird Dog pilot Erenfeld called battalion air officer Engel and excitingly said he saw at least 300 NVA running back to the tree line. Hunnicutt watched Erenfeld’s small Cessna pass far overhead as twilight set in. He had to spend another night on the NVA-controlled hill.

Around 7:15 a.m., on April 18, just like the day before, Hunnicutt’s voice was heard across the valley. “C Company…C Company…One nine Marines…Bearing two two five… Bearing two two five.” Despite numerous wounds, Hunnicutt had moved down off Hill 600 and gotten about 1,000 yards from Hill 689. He was down in a ravine.

A rescue team was assembled but given strict instructions to go only a few hundred yards beyond their unit’s perimeter. It didn’t take long to move that distance and establish verbal communication with Hunnicutt. The team could see him and hear him. But so could the NVA. It was a trap, and everyone knew it. Two Blue Max helos patrolling the area offered to assist. Erenfeld and Engel briefed the Army chopper pilots, and they worked up a plan.

Hunnicutt, lying on his back out in the open, saw Erenfeld’s Cessna fly over the ridge but recoiled when two red-smoke canisters came out its window and landed close by, marking his location. Hunnicutt feared that airstrikes would be called on his position.

Blue Max team leader Warrant Officer Gerald Sommers briefed co-pilot Warrant Officer Sherod Mallow on the rescue plan. Sommers would come in low over the hill and when 200 yards out, fire all 48 of his rockets to lighten the load. Then he would make a downslope approach and probably have to hover while Spc. 5 Alan Heidbreder jumped out and got Hunnicutt. Meanwhile, 2nd Lt. Larry Mobley’s Blue Max Huey would prowl nearby, looking for targets.

Circling high above around 1 p.m., Erenfeld watched as Sommers’ helo came in low from the southwest. A few hundred yards out Sommers fired his rockets. The NVA in the area were not expecting the deadly barrage of 48 rockets. Those who survived prudently kept their heads down. Sommers’ ship dipped into the ravine on the east side of the hill. A downslope approach in a steep-sided valley was extremely dangerous and well outside the safe helicopter operation that Blue Max pilots had learned at Fort Rucker, Alabama. But combat experience had shown them exactly how far they could stretch their aircraft’s capabilities.

As Sommers slowly flew down the ravine, he came alongside Hunnicutt. Heidbreder jumped off the skid, raced over to grab the Marine and got him safely aboard the helicopter. About 500 yards away, the two squads watched through binoculars as North Vietnamese soldiers predictably sprang their trap, jumping up and unleashing a volley of AK-47 rifle fire at the Huey.

Now came the difficult task of getting the helicopter out of there. The main rotor was only feet from the ravine walls, and the tail rotor was even closer. A rotor strike against one of the walls would have likely been

catastrophic, but Sommers deftly lifted the helicopter straight up. Once above the walls, he throttled to full speed and headed to the Khe Sanh base.

Within minutes, Hunnicutt was with lifesaving surgeons—and thinking of others less fortunate. “There’s still guys alive on the hill,” he said. But Hunnicutt was the last live Marine pulled off Hill 600. Four days later, three companies of the 2nd Battalion, 3rd Marines, swept the area.

Following extensive fighting, the bodies of the missing in action from the 1st Battalion, 9th Marines, were recovered but at the cost of six Marines killed and 86 wounded. Hill 600 would unofficially be known by the Marines as “Dead’s Man Hill.”

Panykaninec, like Hunnicutt, survived the nightmare on that hill west of Khe Sanh, but with serious head trauma that had erased his memory of the ordeal. Many involved in the rescue went to their graves not knowing that Panykaninec had survived.

In 2015, Hunnicutt was reunited with the Blue Max crew who picked him up. Lynch, the last surviving member of Blue Max 48, tracked down Panykaninec in 2018, and they talked on the phone. The Army veteran and Marine veteran plan to reunite soon.

John McGuire, a forester and wildlife biologist in South Alabama, has done extensive research on the 1st Cavalry Division in Vietnam.

This article appeared in Vietnam magazine’s February 2020 issue.