An Israeli transport squadron commander recounts the daring air operation to liberate hijacking hostages in Uganda.

Like all Israelis, Lieutenant Colonel Joshua Shani had been closely following the hijacking drama of Air France Flight 139. Commandeered by two terrorists from the left-wing German Baader-Meinhof Gang and two from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP) on June 27, 1976, the Paris-bound flight from Tel Aviv, via Athens, was diverted to Uganda’s Entebbe Airport. The hijackers demanded the release of 53 jailed terrorists, threatening to kill the hostages if their demands were not met by July 1. While the hijacking was officially France’s responsibility, Israel was paying very close attention, since many Israelis and Jews were among the passengers.

In an exclusive interview, Shani recalled: “When we heard about the hijacking, we started to make plans in the squadron—plans that were very basic. We had no idea if anyone would even ask us, but we looked into range, navigation, fuel requirements, payloads we could carry, how we could fly beneath the radar between Saudi Arabia and Egypt, and weather patterns for the time of year—very general preparations, just in case someone would approach us.”

The commander of the Israel Air Force (IAF) soon approached Shani. “I was at a wedding when [Maj. Gen.] Benny Peled personally called me and began asking questions,” he said. “It was a strange situation—the C-130 was a new aircraft in the IAF. The IAF is a fighter aircraft air force. No one really knew the C-130. No one knows the performance. So the chief of the air force calls a lieutenant colonel, the commander of the squadron, and said: ‘Tell me, is it possible—can you fly to Entebbe? How long will it take? What can you carry?’ The very questions we had been asking ourselves. I answered all his questions, leaving him with the impression that a rescue would be feasible.”

One of the plans the military leaders originally came up with involved dropping naval commandos into Lake Victoria. The plan called for them to make their way in rubber boats to Entebbe Airport, which borders the lake, take the terminal, kill the terrorists and free the hostages before asking Ugandan President Idi Amin for safe passage home.

On the third day of the crisis, in a move all too reminiscent of the Nazi “selections” that determined who would live and who would die, the terrorists separated all Israeli and other Jewish passengers from the others, freeing and sending the non-Jews to France the following day. Interviews with freed hostages revealed that Amin’s daily visits to the hostages had been a farce; the Ugandan head of state allowed more Palestinians to join their colleagues at the airport and stationed Ugandan troops to guard the terminal where the hostages were being held. With Amin abetting the hijackers, a rescue would need to physically remove the hostages from Entebbe. Israel decided that it must act.

Ironically, the smaller number of hostages made rescue planning easier. Based on the new intelligence, the plan to drop commandos into Lake Victoria was canceled after much valuable time had been lost. Plans for an airborne hostage rescue operation were accelerated.

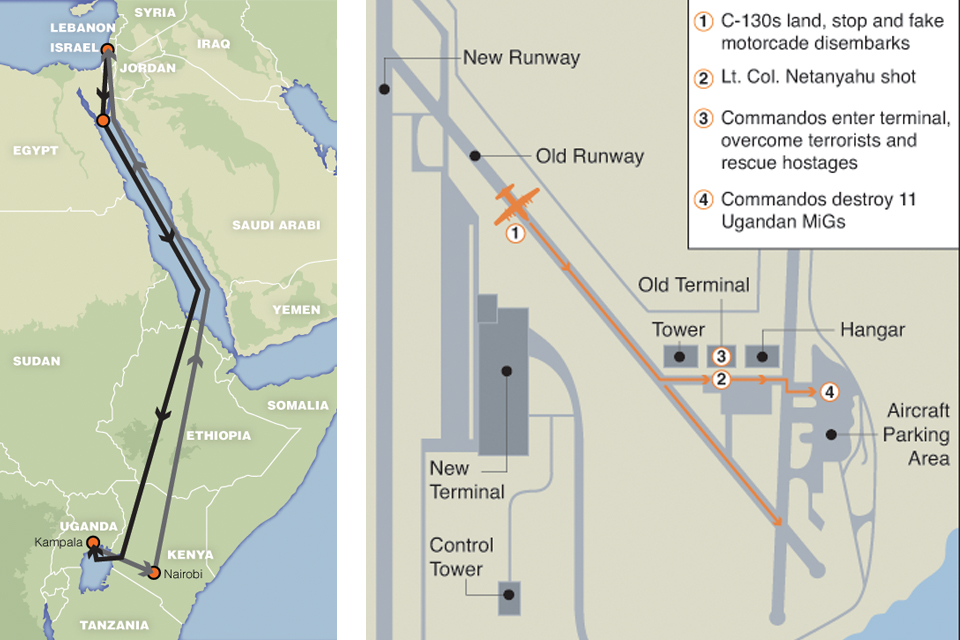

Colonel Shani was tasked with serving as lead pilot for the hostage rescue mission to Entebbe, code-named “Operation Thunderball” (“after the James Bond movie,” according to Shani). It was no easy assignment: The air force was to avoid detection while flying 2,361 miles, land at a hostile airport and deliver a cargo of Israel Defense Forces (IDF) soldiers to Entebbe’s old terminal building to surprise the terrorists, then fly the freed hostages home to Israel.

“We had examined our options,” Shani recounted. “Israel had [Boeing 377] Stratocruisers and Boeing 707s, but the only option to fly low and penetrate, to offload equipment, was the Lockheed C-130 Hercules. Maybe we would encounter a short runway, or require a short takeoff, or no runway at all. Maybe there would be obstructions. There were too many questions. Only the Hercules could carry all the equipment the ground forces needed for the job.”

Shani busied himself with selecting aircrews, which proved to be a challenge. “Everyone was a veteran of transport or even fighter aircraft, and all were of a high level,” he recalled. “I had to close and lock the door to my office and write on the board the names of the crews that would participate. All were veteran pilots who had either flown to Entebbe before or been instructors to the Ugandan air force and knew the airport well.”

Shani explained that Israel had helped Uganda build and train its air force. IAF aircraft had flown frequently to Entebbe in support of these activities, until Libyan influence led Idi Amin to expel his Israeli advisers and adopt an anti-Israel posture.

Next came coordination with the ground forces on how the operation would be carried out. Shani met with Lt. Col. Yonatan “Yoni” Netanyahu, commander of the Sayeret Matkal, an elite commando brigade whose job would be to storm the old terminal, kill the terrorists and free the hostages. Time was critically short: The hijackers’ deadline had already been extended by three days to July 4, when they threatened they would kill the 105 remaining hostages. With the terrorists’ ultimatum fast approaching, there were only two days to plan the operation. “We simply did not have time to plan the thousands of elements that go into such an operation,” Shani said. “The entire operation was planned over 48 hours. Planning an operation like this might take another military a month, two months, six months or more, but we had two days, so we probably covered only 2 percent of the plan, leaving 98 percent to improvisation.”

Shani gave an example: “In case the runway at Entebbe was not illuminated and we couldn’t make out the runway on radar, one of the crew prepared a text: ‘We are East African Airways flight number such and such. We have wounded on board. Please illuminate runway lighting.’ Show me the air traffic controller who wouldn’t have turned on the runway lights.”

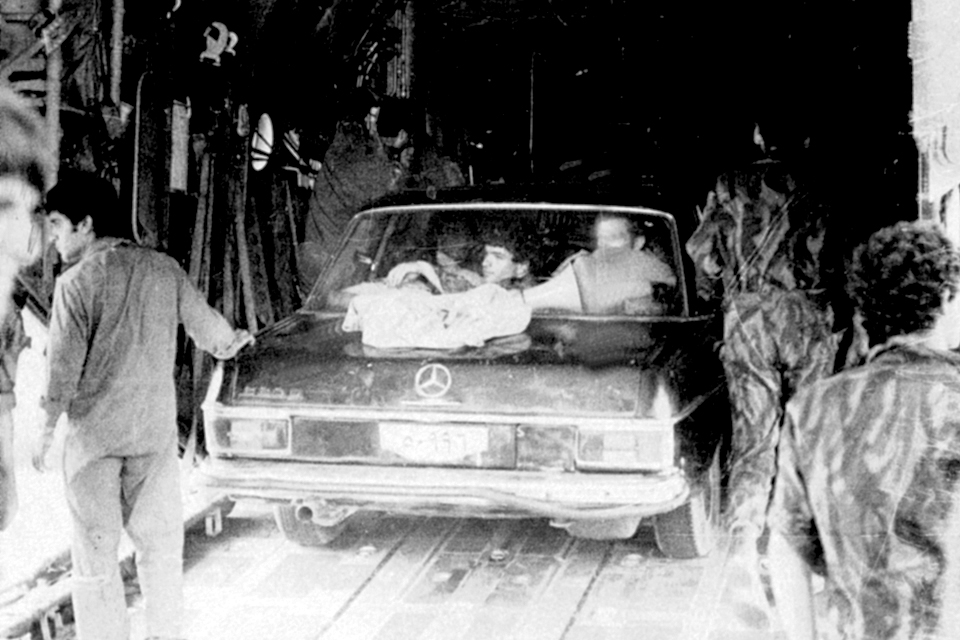

Once on the ground at Entebbe, Shani would have to get the commandos as close to the old terminal building as possible, yet taxiing too close to the terminal would alert the terrorists, who might then open fire on the hostages. The Ugandan president provided the solution to this challenge.

“We watched the CBS news each evening and saw Idi Amin coming to visit the hostages, where he mockingly welcomed them to Uganda,” Shani explained. “He enjoyed the exposure from the world media. He came with a black Mercedes from the runway to visit the hostages in the terminal, escorted by two Land Rover jeeps. So when we made the plan, we thought it would be smart if we used the same thing, and the Ugandan soldiers guarding the building might hesitate, at least for a few seconds. And that’s what was done, and exactly what happened, so they could penetrate into the terminal building. The only problem was that we didn’t have any Mercedes in the IDF, so they rented one. There wasn’t a black one—only a white one, so we painted it. Not a bad deal—we didn’t put much mileage on it!”

There were still many unknowns, so a senior officer would be required in case critical decisions had to be made on the scene. “Decisions such as in the event they needed to destroy an airplane,” Shani explained, “or whether to take Idi Amin’s C-130 if we didn’t have transportation to go back home.” Operation Thunderball commander Brig. Gen. Dan Shomron would fly with Shani in the lead aircraft, followed by three other C-130s.

Two Boeing 707s were added to the mission: one for command and control, and a second to serve as a flying hospital, since many casualties were expected. The command-and-control aircraft was supposed to fly at standoff range from Entebbe when the C-130s landed there, while the ambulance was sent to Nairobi, Kenya. Deputy chief of general staff Maj. Gen. Kuti Adam and IAF commander Peled flew in the command-and-control plane.

Concerned that the Ugandans would cut the runway lights, the military leadership sought assurances from Shani that he could land on an unlit runway—something in which his squadron was not experienced. “We had to practice at Sharm [el Sheik, at the southern point of the Sinai Desert] on landing without runway lights,” he said. “We had to demonstrate, so I did a little trick: I took the airplane out a few hours before just to practice myself to make sure that I can do it, and understand the topography around the runway. Later I demonstrated to the big chiefs.”

With chief of general staff Lt. Gen. Moredechai “Motta” Gur, Maj. Gen. Peled and head of air force operations Avihu Bin-Nun in the cockpit “breathing down my neck,” Shani said he flew two nighttime landing practice runs. “We were using first-generation night vision goggles, which were lousy—really primitive. We demonstrated a radar-assisted landing for the military leadership. I can’t say the practice run went particularly well, but we explained that the difference was a landing at Sharm, which is inland, versus the runway at Entebbe…on the lake edge, which is easy to identify on radar. I told them it would not be a problem. They were happy. I knew that everybody wanted to do the mission, so my job was to help them make the right decision, which I think I did. And they approved the mission.”

Late Friday night, there was a full dress rehearsal using a hastily built replica of Entebbe’s old terminal building. The following day the commandos and infantry completed their preparations, loaded their equipment on the C-130s and flew to Ophir Air Force Base in the Sinai Desert. Timing for a midnight (Israel time) landing at Entebbe dictated a 15:30 hours departure on July 3, at the peak of the afternoon heat.

“The takeoff from Sharm was one of the heaviest ever in the history of this airplane,” Shani said. “It was 30 to 40 percent more than the maximum normal takeoff weight of the C-130 at that time, and I didn’t have a clue what would happen. The aircraft was crowded with Yoni’s assault party, the Mercedes and Land Rovers, and a paratrooper force. I gave it maximum power, and the airplane was just taxiing, not accelerating. At the very end of the runway, I was probably 2 knots over the stall speed, and I had to lift off, and to be airborne I needed to stay with the ground effect, which is like four or five, six meters above the water, to gain a few more knots of airspeed. I couldn’t make the turn, I took off north but had to turn south—the destination was to the south. Just making the turn, struggling to keep control, but you know, airplanes have feelings, and all turned out well.”

The Israeli government had yet to approve the rescue mission, but to maintain schedule the force had to depart, with the option of being called back. Radio silence would be broken only to recall the formation.

“It was a 7½-hour flight to Entebbe from Sharm el Sheik, but we started long before that,” Shani continued. “There was the flight to Sharm, and all the preparations the day before. The flight was physically difficult. We had to fly very close to Saudi Arabia and Egypt, over the Gulf of Suez. The problem was not violating anyone’s airspace—it’s an international air route. The problem was that they might pick us up, so we had to fly really low to avoid radar. And we really did fly low….we flew 100 feet above the water, a formation of four. The main element was surprise. All it takes is one truck to block a runway, and that’s all. The operation would be over. Therefore, secrecy was critical.

“At some places that were particularly dangerous, we flew at 35 feet. I recall the altimeter reading. Trust me, this is scary! In this situation, you cannot fly close formation. As flight leader, I didn’t know if I still had No. 2, 3 and 4 behind me because there was total radio silence. This is something we didn’t cover in the briefing. You can’t see behind you in a C-130. Luckily they were smart, so from time to time they would show themselves to me and then go back to their place in the formation, so I still knew I had my formation with me.

“We were carrying heavy cargo loads in excess of allowable maximums. We had very bad weather, and we encountered thunderstorms by Lake Victoria, which was very unpleasant for the soldiers behind; many soldiers threw up. It was also quite hot. It was very, very difficult. Nobody was strapped in, a total mess, but luckily nothing happened.

“Upon reaching Ethiopia, where we knew there was no radar, we went up to 20,000 feet, and could speak freely on the radio for the last four hours of the flight. I left the formation by the Kenyan-Ugandan border and continued alone, the plan calling for my airplane to land seven minutes before the others, to achieve maximum surprise; the other three aircraft were in a holding pattern, allowing enough time for me to land and taxi to the terminal, [get the] Mercedes and Land Rovers out, and the commandos to storm the building.

“My main problem in this operation was to land quietly, and to do it in one shot, and not have to go around and make noise. And for this I used the Hercules’ airborne radar, which is not designed to do a blind landing. It’s a weather radar, mapping radar, but we used the terrain between the runway and surroundings to do an airborne radar approach. To do so we needed a real picture of how the airport really looked from a 3 degree approach angle. For this we used the Mossad [Israel’s intelligence agency]. What they did for us—they took some pictures of the approach so the navigator could compare the radar picture with something real.

“I was under tremendous, tremendous pressure. It was not fear of being killed or wounded, but fear of failure. The responsibility on my shoulders—I can’t describe how difficult it was. Everything was on me. I had a crew, I had my commander in the 707 and I had communications with the HF radio—all this is true—but eventually there was me. I think my white hair started there, overnight. There was tremendous pressure to succeed. By mistake, I could have created a national disaster. Think about it—how many people would have died at Entebbe if I had made a mistake, so that was the main fear. But I still had the sense—when I was talking on the intercom in the cockpit I was speaking very fast, with high pitch, as one speaks when under pressure. But when the chief of the air force was talking to me from the 707 and asked if I could see the runway, was everything OK, was everything under control, I took a few deep breaths, and answered him in a soft, confident voice. We could see the illuminated runway, but we operated as if the runway was not visible, even though there was no need.”

Entebbe’s skies were overcast, with light rain falling. The C-130’s landing lights went on at the last possible moment to give the least amount of warning of the aircraft’s approach. Shani touched down at 2300 Uganda time, just 30 seconds behind plan. The Hercules cargo ramp was lowered and the Mercedes’ and Land Rovers’ engines started.

“I stopped in the middle of the runway,” Shani said, “and a group of paratroopers jumped from the side doors and marked the runway with electric lights—a 600-meter runway, because we expected something would happen, that someone would switch off the lights when the shooting would start. I left them there. The paratroopers went on to take the control tower.

“I turned right and taxied toward the old terminal building, stopping far enough from the terminal so they wouldn’t hear our aircraft, yet close enough so that the Mercedes and Land Rovers would have a short trip to the terminal. The Mercedes and Land Rovers drove out from the back cargo door of my airplane, and the commandos stormed the old terminal building.”

When a pair of Ugandan sentries challenged the motorcade, the assault team opened fire. Fearing the terrorists might be alerted by the gunfire, the commandos raced toward the terminal building. They exchanged gunfire with both terrorists and Ugandan troops. Co – ordinating the assault from outside, Sayeret Matkal’s commander, Yonatan Netanyahu, was fatally struck by a shot fired by a Ugandan soldier in the control tower. (The operation was later renamed “Operation Yonatan” in his memory.) Another soldier was badly wounded, and three hostages were killed in the crossfire.

By the time the other three C-130s began landing seven minutes after Shani’s aircraft had touched down, all seven terrorists had been killed and the hostages freed. Some 45 Ugandan soldiers also lost their lives that night. While Hercules No. 3 was approaching, the Ugandans cut the runway lights, but it landed safely. The last C-130, whose job was to pick up the hostages, landed with the aid of the lighting laid out by the paratroopers and taxied close to the old terminal building.

Armored personnel carriers and infantrymen offloaded and took up positions around the airport; the APCs secured the area around the old terminal building while infantrymen sealed off access to the airport and took control of the new terminal and control tower, allowing time to refuel and for the hostages to be safely evacuated.

The aircrews remained busy. “We had a little problem: We needed fuel to fly back home,” said Shani. “Minor issue—it was a one-way ticket! We brought a fuel pump that we planned to connect to the underground fuel you have in international airports, and to refuel the airplanes. The other plan was to take off and land at an alternate destination to refuel, Nairobi being the preferred place, but nothing was confirmed, nothing firm. When the command-and-control aircraft flying overhead informed us ‘the Nairobi option is open,’ we were already hooked up to the fuel and starting to refuel. But the Ugandans had lost control and were shooting all over the place with tracers….Trust me—it’s not pleasant to sit there and to see the tracers around you. You need just a few holes in an airplane to ground an airplane, so I made a decision to stop the refueling and to fly to Nairobi.

“Before radio contact with the command-and-control aircraft was lost as the 707 went out of range, the air force chief called over the net: ‘Don’t forget the MiGs,’” recalled Shani, referring to the Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17 fighters based at Entebbe. “Theoretically the MiGs could chase us after takeoff. It was very theoretical because they didn’t have any night capability. But Idi Amin deserved this. It was the job of [Shaul] Mofaz, who years later became minister of defense in Israel, to destroy these MiGs. Mofaz’s force took out about eight to 12 aircraft. The ensuing explosions lit up the night sky, clearly revealing our aircraft parked on the tarmac. I was nervous, but all ended well.

“After some 45 to 50 minutes on the ground, we were ready to go. I gave the order: ‘Whoever is ready, take off.’ I remember the satisfaction of seeing the No. 4, with the hostages on board, taking off from Entebbe—the sight of its silhouette in the night. It was then I knew. That’s it. We did it. The mission succeeded.

“The short stopover in Nairobi provided the first moments to relax,” continued Shani. “Between half an hour to an hour we were on the ground in Nairobi, just to get some relief for the troops after being in the airplane for so long….During the refueling, it was my only opportunity to see the hostages. I walked from my airplane to the hostages’ airplane. They were still inside—all of them, about 105 of them, with some lying on the ground, and I tried to talk to some of the people but you couldn’t talk to them at all. They were confused, in total shock. What I saw there is something I will remember forever. I still remember the facial expressions, all the way from hysteria, fear, relief, exhaustion, happiness and exhilaration. I saw all the expressions that exist in the world in one short look at this group of 105 people. It was a very strong picture.

“We were still a long way from home, with an eight-hour flight ahead of us. Word had already leaked out that something had happened at Entebbe, and this was being reported by French media and the British BBC. We tuned the long-range radios on the airplane to the news, and were shocked to hear [Minister of Defense] Shimon Peres acknowledge that we were on our way back from Entebbe with the hostages. We were only by Ethiopia, with a very long way yet to fly, and they are talking about us. We flew by Egypt, and this was before the peace treaty, so Egypt was an enemy. A formation of [IAF McDonnell Douglas] F-4 Phantoms greeted us by Ras Banas, not far from the Egyptian-Sudan border, and escorted us back home.”

The four aircraft landed at Tel Nof Air Force Base. Hercules No. 4 with the freed hostages continued on to Ben Gurion Airport, where they were reunited with jubilant family members. “The other three airplanes remained for a debrief just to get some hot information before it gets lost,” Shana said. “Here comes Yitzhak Rabin, prime minister of Israel, walking up to me….I’ve been in my flying suit for 24 hours straight, in temperatures over 100 degrees in the airplane, sweating and smelly, and here walks the prime minister with big open arms. I’m thinking, please don’t hug me—he may die from this! He hugged me for what felt like a full minute, and said only, ‘Thanks.’

“Coming home, there was immense euphoria, combined with overwhelming fatigue. For me and for the deputy leaders and senior navigators, the operation was three to four days without any sleep. The adrenalin must have been working overtime, but that combination of total weariness and total excitement is a wonderful feeling.”

Uganda protested the Israeli raid as a violation if its sovereignty and unsuccessfully sought UN condemnation of Israel. Idi Amin was humiliated by the hostage rescue, his reputation tarnished. On Amin’s orders, an elderly hostage who had been taken to a local hospital was dragged from her hospital bed and murdered, and Amin reportedly ordered the execution of all the Entebbe airport workers. His brutal rule would continue until April 1979, when he fled the country after defeat in an equally humiliating war with neighboring Tanzania.

Operation Yonatan brought new respect for the IAF transport wing. For Lt. Col. Joshua Shani, it was a career highlight. In his 30-plus years serving in the Israel Air Force, Shani would accumulate 13,000 flight hours, among them 7,000 in C-130s. Over the years, Shani commanded three squadrons and a mixed base of four squadrons and eight ground units. He retired as a brigadier general after serving as the air force attaché at Israel’s embassy in Washington, D.C.

For further reading, Israel-based contributor Gary Rashba recommends Yoni’s Last Battle, by Iddo Netanyahu.

Originally published in the March 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.