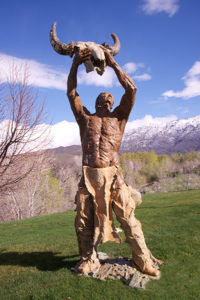

It is little wonder Utah master sculptor Greg Woodard was drawn to create railroad-themed pieces, given that he lives a short drive east of Golden Spike National Historical Park in Promontory, where the Transcontinental Railroad was completed in 1869. “Historical—I’m way into that,” he affirms. But the 61-year-old self-taught artist from Brigham City puts a different slant on history. A buffalo strolls along the tracks in Into the Sunset, while a golden eagle perches atop a rail in Looks West. His American Indian-themed works Ghost Rider, Eagle Wind and Buffalo Medicine also incorporate animals. Of course, an interest in wildlife also comes naturally for the onetime master falconer, who has won multiple awards for his decorative and interpretive carving from the Ward Museum of Wildfowl Art in Salisbury, Md. Call him a Renaissance birdman.

“As a kid, I was drawing all the time, always wanted a new paint set, but then I started ski racing, and I just thought [art] was too nerdy or something,” Woodard says. Later, however, he noticed that his father, a shop teacher, “was real creative, and he did all these really cool projects, some of which were bird carving.” Young Woodard started whittling away, and at age 25 he dove headfirst into the craft.

But while bird carving was artistically and financially rewarding, the detail work proved time-consuming. “I would average probably two birds of prey a year, and it takes a while to build up enough inventory to even approach a gallery,” he says. “Then the shows started dropping the prize money, and I could just see [the market] crumbling.”

Woodard moved to casting bronze sculptures and now also works with concrete, steel and rebar with a few barrels thrown in for good measure. “I need a tetanus shot,” he jokes.

“The stuff I’m doing now,” Woodard explains, “I build them, like I did my bronzes. You build up; they’re additive sculptures instead of subtractive sculptures. And there’s really quite a bit of difference between the two. Subtractive sculpture is not forgiving. You take too much off, and you’re done. It’s a good way to learn to do subtractive first, because it teaches you to think about what you’re doing.”

Woodard moved to casting bronze sculptures and now also works with concrete, steel and rebar with a few barrels thrown in for good measure. ‘I need a tetanus shot,’ he jokes

All that carving of birds of prey out of wood came in handy. “I used to carve out these huge logs,” he says. “Started my pieces with a chainsaw. You get places fast.”

He enjoys the freewheeling approach to working with concrete. “I’m doing pretty complicated armature, and you have to go fast with concrete before it sets.” Most sculptors dry-blast their molds after a casting has been completed, but Woodard prefers to chip it clean by hand. “It takes a few days,” he says, “and I ‘leave’ the material—make it look like it’s a fossil. That’s from my interest in archaeology.”

What he learned working with bronze has helped him with his new medium. “I’ve had to figure out different ways to do the patina,” he says. “I can color them up pretty good by using the same elements on concrete that I used on the bronze pieces. The copper will make it green, and then it’s basically rust. You can make them look real. It’s kind of cool.”

Woodard’s work is carried by Altamira Fine Art in Jackson, Wyo., and Scottsdale, Ariz.; Manitou Galleries in Santa Fe, N.M.; Creighton Block Gallery in Big Sky, Mont.; and Frame of Reference Fine Art in Whitefish, Mont. He’s working on new pieces for an exhibition later this year at the Booth Museum in Cartersville, Ga.

Woodard’s busy days start with a trip to the gym for CrossFit training and boxing. “Then I get back as quick as I can, and I do these pieces hard in the morning.” He works outside on his sculptures, napping in the heat of the afternoon before hitting it again in the evening as it cools.

“It’s work,” he says, “but it’s fun.” WW