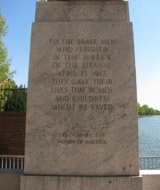

Just past midnight on April 15, 2012, a group of 20 men in tuxedoes lined up at the base of the Women’s Titanic Memorial in Washington, D.C. As a mild breeze rolled across the Washington Channel, a bell tolled. The crowd of more than a hundred people immediately hushed. A liveried waiter distributed flutes of champagne. One by one, the men gave toasts in honor of the famous ship that sank in the North Atlantic exactly 100 years ago. “To those brave men,” the men repeated, raising their glasses. “Hear, hear,” the crowd responded.

This is the 34th year that the Men’s Titanic Society, as this exclusive group is known, has held a ceremony at the memorial in honor of the men on the Titanic who sacrificed their lives so that women and children could be saved. Their ritual is just the latest chapter in the long history of this memorial, a history that features many notable names—much like the Titanic manifest itself—but is largely unknown to most Americans.

This is the 34th year that the Men’s Titanic Society, as this exclusive group is known, has held a ceremony at the memorial in honor of the men on the Titanic who sacrificed their lives so that women and children could be saved. Their ritual is just the latest chapter in the long history of this memorial, a history that features many notable names—much like the Titanic manifest itself—but is largely unknown to most Americans.

Titanic memorials can be found around the world, including famous ones in Belfast, Northern Ireland, where the ship was built, and New York City, its intended destination. The Women’s Titanic Memorial, however, is unique in that it was conceived, designed, and funded by some of the most prominent women of the early 20th century.

Planning and fundraising began within a month of the sinking. Helen Herron Taft, wife of President William Howard Taft, gave the first recorded donation to the Titanic Memorial committee, which was chaired by Clara Hay, the widow of Secretary of State John Hay. Titanic survivors and family members were prominent contributors, including the wife of Pennsylvania railroad magnate John Thayer, who went down with the ship, and Mrs. Archibald Forbes, who donated the cash she had won playing bridge against the doomed John Jacob Astor the night the ship hit the berg.

Fundraising parties, benefit concerts, and other events were held in Washington, New York, and elsewhere. An impromptu collection was even taken up aboard the ocean steamer Berlin in July 1912, as it crossed near the spot where the Titanic went down. By that summer, the Women’s Titanic Memorial Committee reported a daily haul of $300 in donations. In all, they received more than $40,000.

Early fundraising efforts referred to the proposed memorial as an “arch,” even before a designer had been secured. Charles Dana Gibson, whose drawings popularized the so-called “Gibson girl,” drew up a speculative poster to be used for fundraising that showed a classical female figure standing before a stone, memorial-style building.

After a women-only design competition, sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (newspapers called her a “sculptress”) won the bid with her proposal for an angelic male figure with a raised head and outstretched arms. (She would go on to found the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.) The base was designed by Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial, and the statue was carved in granite by the Horrigan Studio of Quincy, Mass.

After a women-only design competition, sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney (newspapers called her a “sculptress”) won the bid with her proposal for an angelic male figure with a raised head and outstretched arms. (She would go on to found the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.) The base was designed by Henry Bacon, architect of the Lincoln Memorial, and the statue was carved in granite by the Horrigan Studio of Quincy, Mass.

The memorial was not without controversy, however. Philanthropist Evelyn Gurley-Kane wrote a letter to the The Washington Post in 1914 stating that a memorial only to men was a “strange affront to … the women, whose bravery was even greater than the men’s, and it is man’s privilege to help protect women and children if he is any sort of man.” Others thought the funds should be used to help sailors in need and their families. One Washington Post letter-writer even suggested that the memorial also recognize the captain and crew of the rescue ship Carpathia.

Despite the complaints, work progressed and a prominent site was chosen along the Potomac near Rock Creek Parkway, which Col. Ulysses S. Grant III, the city’s director of public buildings and parks, helped to secure. On May 26, 1931, Mrs. Taft had the honor of dropping the veil on the completed memorial. For three decades, the memorial was highly visited and used for public gatherings. When the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts was built in the mid-1960s on the same spot, however, the Women’s Titanic Memorial was mothballed for two years until it was unceremoniously moved to its current location, a quiet, out-of-the-way spot on the capital’s Southwest waterfront.

The memorial might have remained obscure if Jim Silman, founding member and president of the Men’s Titanic Society, hadn’t grabbed three like-minded friends to honor the Titanic Memorial in 1979. The exclusive society, whose invitation-only membership rarely tops 20 and includes only media and journalism types, has met after midnight every April 15 since.

The memorial might have remained obscure if Jim Silman, founding member and president of the Men’s Titanic Society, hadn’t grabbed three like-minded friends to honor the Titanic Memorial in 1979. The exclusive society, whose invitation-only membership rarely tops 20 and includes only media and journalism types, has met after midnight every April 15 since.

“These fellows came along at a time when virtually nobody knew there was a Titanic Memorial in Washington,” says Michael Freedman, a seven-year member who is a public broadcasting producer. “They took it upon themselves to honor the 1,500 brave souls who perished in the disaster.”

“There are always new stories being discovered about the Titanic,” says Silman, a former television producer. “We thought about doing something more elaborate in honor of the centennial. But we’re traditionalists. We just did what we always do. We’re dedicated to this memorial.”

About the Author

Based in Arlington, Virginia, Kim O’Connell is a regular contributor to Civil War Times, and her work has appeared in Preservation, Architect, National Parks, NationalGeographic.com, Traditional Building, and the Washington Post, among others. She is a longtime Titanic history buff, although she prefers the term “Titaniac.”