In the February 23, 1864, issue of his newspaper, the Raleigh (N.C.) Standard, William Woods Holden announced that he was suspending publication. The Confederate Congress had just passed a law empowering the government to imprison people without trial. The writ of habeas corpus, by which prisoners can demand to be either released or tried on specific charges (and which President Abraham Lincoln had himself suspended in the North back in 1861), would no longer protect antiwar agitators in the South.

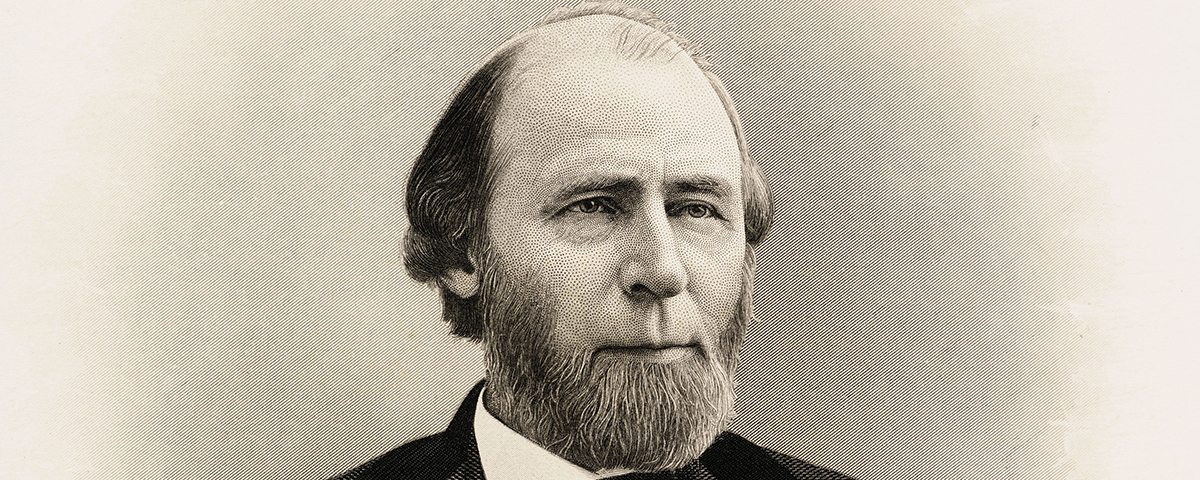

Holden, born on November 24, 1818, in Orange County, N.C., had steadily assumed a leadership role in his native state, although this often meant sacrificing political consistency amid the rapid whirl of events in the Civil War era. He started as a supporter of slavery, but his fall came when be stretched his authority to the breaking point to defend former slaves and their supporters from the murderous Ku Klux Klan during Reconstruction.

Holden was the illegitimate son of Thomas Holden, a mill owner, and Priscilla Woods. The stigma of his birth, it seems, affected Holden by making him ambitious, determined to forge an identity for himself as a self-made man.

Learning the printing trade as a boy, as a young man Holden worked on the Whig newspaper the Raleigh Star, for which he frequently contributed articles. His work at Whig papers impressed the opposition Democrats, who offered him the chance to edit a Democratic newspaper, the Raleigh Standard, which Holden took over in 1843.

Seeking to revive a flagging Democratic Party, Holden attacked the Whig Party’s allegedly aristocratic tendencies vis-à-vis the “common man” (i.e, the white common man). Democrats gave Holden’s Standard articles much of the credit for their party being able to assume the state’s governorship and legislature throughout the 1850s. Holden became head of the Democratic State Committee, recognition of his kingmaker status.

In 1856, slavery came under attack from a new political party in the North and West. The Republican Party nominated John C. Frémont for president on a platform of keeping slavery out of the federal territories. To Holden, Frémont’s election would justify secession. He went so far to print a report in the Standard that an unnamed member of the faculty at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill was a Frémont supporter. The “unnamed” Republican infiltrator was chemistry professor Benjamin Sherwood Hedrick. Holden was not appeased when Hedrick wrote to the Standard to defend his position, and he printed angry editorials against the university for employing a Republican. The university soon fired Hedrick and, faced with personal threats, Hedrick left North Carolina.

By 1858, Holden had decided that it wasn’t enough for him to be a kingmaker—he wanted to be governor of North Carolina in his own right. He sought the state Democratic Party’s nomination but, despite considerable support, lost to state superior court judge John Willis Ellis. Holden was deeply hurt by his loss, attributing it to dirty tricks by aristocratic elitists and ex-Whigs, but he loyally supported his party’s nominee and Ellis was elected. In another blow (more than a half-century before U.S. senators were elected by popular vote), the Democratic state legislature around the same time refused to elect Holden to the U.S. Senate.

In both 1859 and 1860, Holden again defended slavery against one of its local critics—Wesleyan evangelist Daniel Worth, a fellow native Tar Heel. Worth was arrested in the Greensboro area for circulating a well-known antislavery book by North Carolinian Hinton Rowan Helper, Impending Crisis. Holden publicly regretted that Worth could not be killed. Far from being killed, thanks to the intervention of influential figures like his non-abolitionist cousin Jonathan, the elderly antislavery activist was allowed to skip bail and leave the state.

Holden, however, turned against secession in 1860, speaking of the dangers of disunion, which he predicted would lead to “civil and servile war…throughout long and cruel years.” In fact, when Republican Abraham Lincoln was elected on an antislavery platform, Holden wrote that Lincoln’s election by itself was not a sufficient reason for secession—a stark reversal of his 1856 position regarding Frémont. The Democratic state legislature retaliated by replacing Holden as state printer, but most voters initially agreed with Holden, rejecting secession proposals. The situation changed in April 1861 with the Confederate attack on Fort Sumter and the subsequent urgent call by Lincoln for troops to use against Deep South secessionists. Holden was elected to a state convention to consider secession, and he joined a unanimous vote to have North Carolina join the Confederacy.

The war hit close to home when Holden’s son, Joseph, joined the Confederate Army and was taken prisoner in a battle with Union troops on Roanoke Island, N.C., in February 1862. The Federal naval and ground assault on the state’s coastal counties seized much of North Carolina’s eastern coast. In the Standard, Holden sought to rally North Carolinians to extra effort in the wake of the disaster, publicizing alleged Union atrocities.

With allies among former Whigs, who joined him in forming the new Conservative Party, Holden campaigned for Confederate colonel and ex-Congressman Zebulon Vance as a candidate for governor. The Conservatives capitalized on popular discontent with Confederate authorities in Richmond and their allies in the Ellis administration. The new Confederate conscription law could lead to “ruin and devastation,” Holden warned, deploring the law’s favoritism to the rich. Vance overwhelmingly won the election and took office September 8, 1862, pledging to support the war while resisting Confederate encroachments on popular and states’ rights.

Vance and Holden defended Richmond Mumford Pearson, the chief justice of North Carolina, who often sought to protect North Carolinians from Confederate military and conscription authorities. Using habeas corpus, Pearson ordered the release of prisoners he deemed the Confederates were holding illegally.

By mid-1863, Tar Heel residents were resisting the war in many ways. Blacks often fled to Union lines to escape slavery. Whites were restive under Confederate conscription, property seizures, and food shortages. A war-within-the-war ravaged the central Piedmont counties, as Southern troops and pro-Confederate state “Home Guards” battled Rebel deserters and Unionist sympathizers. Unionists and other malcontents were smuggled out of the state along old Underground Railroad routes. To help the effort, Colonel George W. Kirk of Tennessee led a force of eastern Tennessee–western North Carolina Unionists by raiding Confederate targets. Beginning in 1863, anti-Confederate protest meetings were frequently held within the state.

The North Carolina peace movement paralleled the views of Northern “Copperheads” such as Clement Vallandigham—both groups wanted a negotiated reunion with slavery retained. In March 1863, Holden began making pleas for a negotiated peace with the North, without specifying detailed terms.

Georgia troops moving through Raleigh rioted and attacked the Standard’s offices in September. In reprisal, Holden’s supporters attacked a pro-Confederate Raleigh newspaper, the State Journal. Vance threatened President Jefferson Davis that future attacks against dissenters would prompt him to withdraw North Carolina troops from the Confederate Army. Davis agreed that the attacks would stop.

Vance privately shared Holden’s doubts about whether the Confederacy could win the war; however, Vance did not support the growing peace movement in North Carolina. Vance feared that if peace forces were elected in North Carolina and the Union subsequently won, then in the inevitable postwar recriminations, North Carolina might be accused of causing the defeat by stabbing the Confederacy in the back.

As a result, Holden and Vance broke with each other, with Holden pushing for a negotiated peace and Vance for sticking with the Confederacy. To put his case to the public, Holden ran for governor against Vance in the 1864 election.

The governor’s supporters focused on defending Vance as the real peace and civil liberties candidate, while denouncing Holden’s secessionist past. Holden found it necessary to revive the Standard in May 1864 to deal with the attacks. Confederate officers obliged North Carolina soldiers to vote for Vance, and Confederate authorities often threatened Holden’s supporters. The presence of Confederate troops at polling places—supposedly on the lookout for deserters and Unionist guerrillas, but also to keep peaceniks from voting—also served to discourage Holden’s supporters. When the ballots were counted that fall, state authorities announced that Vance had won re-election by a landslide: 58,070 votes to Holden’s 14,491.

As both Holden and Vance had anticipated, Union forces conquered the Confederacy. Northern troops poured into North Carolina in the wake of Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865 and the succession of Vice President Andrew Johnson, a Tennessee Unionist.

To run the civil administration in conquered North Carolina, Johnson appointed Holden as provisional governor in May 1865. The appointment set the tone for the new president’s Reconstruction policies throughout the former Confederacy. Holden was to supervise elections to a pro-Union state convention. The electorate was to remain all-white—Holden opposed black voting just as Johnson did. Holden was also responsible for deciding which ex-Confederates could take part in politics—Johnson generally accepted Holden’s recommendations for whom should receive pardons and thus regain their political franchise. Holden obtained pardons for those he thought would back his policies, as well as giving government appointments to his supporters.

In cooperation with state treasurer Jonathan Worth—the non-abolitionist cousin of Daniel Worth—Holden managed to recover some state property from the federal government. Holden meanwhile clashed with officers commanding the Union occupying forces. The governor complained about the alleged threat posed to whites by black soldiers. Holden also protested when white civilians accused of crimes against blacks were brought for trial before federal military commissions instead of state courts. The military authorities replied that, unlike federal military courts, the state courts would not even accept black testimony against whites. Holden worked out a modus vivendi with the U.S. military whereby the state courts would take jurisdiction in cases where only whites were involved, and military tribunals would be able to try cases affecting blacks until they won equal testimonial rights in state court.

Holden and Jonathan Worth clashed over North Carolina’s Confederate debt, which Holden—reflecting what he considered Johnson’s wishes—hoped would be immediately repudiated. Worth was less willing to repudiate the debt. In December 1865, Holden and Worth squared off in a (whites-only) gubernatorial election that Worth won. Worth became governor; Holden went back to editing the Standard.

While the convention called by Holden had abolished slavery in North Carolina, backed up by the 13th Amendment, a committee appointed by Holden had recommended a discriminatory “Black Code” for former slaves. But Holden again began adjusting his political thinking, and again he aligned himself with a new political group: President Johnson’s Congressional Republican foes, the so-called “Radical Republicans.” By 1867, Republican leaders in Congress had hammered out a new policy for the former Confederate states. These states must accept a new constitutional amendment—the 14th—which protected basic rights of the freed slaves while limiting ex-Confederate participation in politics. Voting rights would have to be extended regardless of race. Holden was one of the founders of the North Carolina Republican Party, whose platform was based on support for Congress’ Reconstruction plan.

For the fourth time, Holden ran for governor. He had lost in 1858, 1864, and 1865, but in 1868 he finally succeeded, thanks to the support of the newly enfranchised African-American voters and a significant minority of whites (Thomas “Tom Dooley” Dula, a convicted murderer and client of Zebulon Vance, supposedly warned against Holden just before being hanged). Holden won the governorship as state voters approved a new egalitarian state constitution. One of the significant items in this Reconstruction Constitution was a guarantee that habeas corpus could never be suspended, even in emergencies. Congress agreed to restore North Carolina to the Union in 1868 and end federal occupation.

As governor, Holden left the editorship of the Standard and tried to promote the state’s economic development while expanding the rights and educational opportunities of former slaves. He advertised North Carolina in the hope of attracting migrants from elsewhere in the country. Unfortunately, in his desire to improve the state’s transportation network, he listened too eagerly to the promises of crooked would-be railroad developers. These developers obtained state bonds by bribing legislators—though not Holden, who was gullible but not corrupt. When the bribery was exposed, it turned out to be bipartisan—leaders from both the majority Republicans and the opposition white-supremacist Conservatives had taken bribes. The Conservatives had the same name as Holden’s Civil War party but now consisted of anti-Reconstruction forces, including many of the zealous Confederates whom Holden had opposed during the war. In 1876, the Conservatives would be renamed the Democratic Party of North Carolina.

By 1868, armed bands formed in support of the Conservatives and the return of antebellum white supremacy—and in opposition to Holden and the Republican legislature. Masked and robed in white, and generally styling themselves the Ku Klux Klan, these terrorists intimidated, beat, and sometimes killed Republican Party supporters, as well as blacks suspected of any supposed “crime” or of disrespect to whites. In 1869 and 1870, Holden sent detectives to investigate crimes by the Klan and Klan-affiliated groups. The investigations produced indictments, but never convictions, because of Klan sympathizers in the judicial system and the willingness of Klansmen to back each other’s phony alibis. In some counties, Holden got the terrorists to back down by threatening to declare a state of insurrection and send in troops.

In Alamance and Caswell counties, the terrorism climaxed with two political assassinations. Wyatt Outlaw, a prominent black Republican politician in Alamance County, was killed in February 1870, as was a potential black witness to the murder, William Puryear. Holden appointed John Walter Stephens, a white former Republican state senator, to investigate Klan atrocities in Caswell and Rockingham counties. Klansmen, however, murdered Stephens in the Caswell County courthouse in May 1870 after luring him into an unused room in the building. The sheriff, himself a Klansman, showed no interest in seeking justice.

Federal military tribunals had stopped trying civilians once North Carolina was restored to the Union at the time of Holden’s election. But Holden decided to hold military trials, under state authority, to deal with the Klan. Some prompt convictions and executions by firing squad could tame the terrorists, he believed.

Holden declared Alamance and Caswell counties to be in a state of insurrection, and called together a militia, commanded by William J. Clarke and the Tennessean Unionist George Kirk. Kirk’s troops (some of them Union Army veterans) were mountaineers from western North Carolina, plus some from across the state line in eastern Tennessee. Clarke commanded white and black troops from the coastal part of North Carolina. President Ulysses S. Grant agreed to provide supplies to Holden’s militia. He also deployed federal troops, but these U.S. troops made only one arrest.

Holden’s militia—roughly 600 men, about 60 of whom were black—swooped into Caswell and Alamance counties and arrested about a hundred suspects in the Outlaw and Stephens murders and other crimes—the two county sheriffs were among those arrested. The suspects were held in preparation for the military trials that Holden planned. Josiah Turner Jr., the pro-Klan editor of the Raleigh Sentinel, was also arrested. Prominent citizens, hoping to be amnestied in return for their cooperation, went to the Caswell County Courthouse to make confessions of Klan activity in exchange for leniency.

The prisoners and their lawyers turned to Chief Justice Richmond Pearson, now a Republican. Pearson issued habeas corpus writs for Turner and the suspected Klansmen. Holden defied the writs, proclaiming that the civil courts must not interfere with the impending military trials of the prisoners.

Unable to get help in the state courts, the Klan suspects went to George W. Brooks, a federal district judge, who also issued writs of habeas corpus. Holden wanted to defy Brooks as he had defied Pearson, but Grant’s attorney general, Amos Akerman, told Holden to obey the federal court. Holden folded and agreed to have the prisoners brought before Pearson and Brooks, who declared the prisoners entitled to trials in state civil court. The cases, predictably, soon collapsed without convictions.

In an atmosphere of reactionary white resistance to Holden’s actions, combined with continuing Klan-led terror and intimidation of Republican voters in those counties where federal troops and state militia were scarce, the Conservatives took over the state legislature in the 1870 elections. One of the first orders of business in the state House of Representatives was to launch a political vendetta—the House voted impeachment charges against Holden. The charges were sponsored by Conservative representative Frederick N. Strudwick, a Klansman from Holden’s own Orange County who had plotted unsuccessfully to murder an anti-Klan Republican state senator, T.M. Shoffner. (Shoffner prudently had taken the hint and fled the state, however.) Holden was accused of wrongly declaring Alamance and Caswell counties to be in a state of insurrection. He was also accused of defying Pearson’s habeas corpus orders.

Around this time, whether they actually met in person or not, Holden’s career overlapped that of Frederick Douglass. In his Washington, D.C., newspaper the New National Era, established in 1870, Douglass deplored Holden’s prosecution and reprinted an item from another Republican newspaper saying that “If Gov. Holden should be convicted, a reign of terror will be inaugurated by the jubilant Ku-Klux of” North Carolina.

The charges against Holden were tried in the state Senate, with Pearson (despite being involved in the events described in the impeachment) presiding over the proceedings. While leaving his defense to be handled by his lawyers, Holden went to Washington to get away from North Carolina. He wanted to alert federal authorities to the danger faced by the friends of Reconstruction in North Carolina. Fear for his personal safety could have been a factor, too. The prosecution took a disingenuous “see-no-evil” approach, failing to acknowledge the extent of Klan violence in Alamance and Caswell counties. But thanks to rulings by Pearson, Holden’s lawyers were able to present evidence of the Klan terror in these counties. Ultimately, enough senators were convinced of the reality of Klan terror that they acquitted Holden on the state-of-insurrection charges.

When it came to his defiance of Pearson’s habeas corpus writs, two-thirds of the state Senate voted to convict Holden. The Senate removed Holden from the governorship effective March 22, 1871, and prohibited him from holding any state office again for the rest of his life.

Republicans in Washington made Holden the editor of a newspaper in the city, the Washington Daily and Weekly Chronicle. During his brief and successful editorship, Holden supported the federal government as it undertook its own prosecution of the Klan—enforcing new Congressional statutes providing for trial of Klan defendants in federal civil (not military) courts. The federal authorities acted on evidence they had gathered on Klan activity in the South, including the information revealed at Holden’s trial. Roughly 30 North Carolina Klansmen were convicted, serving their terms in a federal prison in Albany, N.Y.

In a letter in late 1871, Holden looked forward to undoing his impeachment. If Republicans took back the legislature, he wrote, “we can rescind or expunge the whole proceedings.” There was at the time one example of an impeachment being expunged: The California legislature in 1862 had impeached state judge James H. Hardy and convicted him of making drunken toasts to Jefferson Davis. After a Democratic takeover in 1870, California’s legislature ordered the impeachment proceedings against Hardy expunged.

A few years after Holden wrote his 1871 letter, Nebraska would set another precedent, expunging the impeachment and conviction of its first governor, David Butler, for illegally mingling public and private business. But since the Republicans did not take back the North Carolina legislature during Holden’s lifetime, the issue of expungement turned out to be, for the moment, theoretical.

Early in 1872, Grant made Holden the federal postmaster of Raleigh, a position he held until President James A. Garfield replaced him in 1881. Holden continued playing a role in the now-minority state Republican Party, and he worked on his memoirs. There were abortive efforts in the state Senate to remove his political disabilities without expunging his impeachment. While Holden suggested he might accept such limited relief, he would not seek it—“I cannot beg for my pardon,” he wrote in his memoirs, “and thus admit my guilt any more than Mr. [Jefferson] Davis can. If he should do that, I should feel that I had lost part of my respect for him.” Holden died unpardoned on March 1, 1892. (Jefferson Davis similarly had died unpardoned three years earlier, but in 1978 Congress posthumously restored Davis’ political rights.)

A story by Thomas Dixon Jr.—son and nephew of Klansmen and a pro-Klan novelist whose 1905 novel The Clansman was the basis for D.W. Griffith’s groundbreaking 1915 film Birth of a Nation—contrasts with Holden’s avowed refusal to seek a pardon. In his memoirs, Dixon recalled his days as a young state legislator in the mid-1880s. Holden supposedly made a cringing appeal to Dixon, seeking restoration of his political rights. Regardless of whether Holden made such an appeal, Dixon’s description of his reaction is probably an accurate account of why Dixon and other Democrats refused to restore Holden’s rights. Dixon says he indignantly recalled the imprisonment of alleged Klansmen—“brave men of my race”—after conviction in federal court, and thus refused to interfere on Holden’s behalf. In short, Dixon blamed Holden, not for violating Klan suspects’ civil liberties, but for daring to support the imprisonment of Klansmen at all. “The verdict” against Holden, Dixon wrote in his memoirs, “was just. The future will sustain it.”

In 2011, a proposed joint resolution to pardon Governor Holden posthumously was passed by the North Carolina Senate but died in the state House amid controversy over Holden’s legacy. Today, Holden supporters still want the late governor’s impeachment to be formally undone. They argue that the legislature did not convict Holden out of zeal for civil liberties and habeas corpus, but because of sympathy for the Klan terrorists who subverted North Carolina’s first attempt at a biracial democracy—a democracy Holden had been trying to build.

Max Longley, an independent scholar based in Durham, N.C., is a member of a committee to commemorate the bicentennial of William Woods Holden’s birth.