Before the fateful B-24 flight, tail gunner Claude Ray wrote his parents that he hoped to return to Kansas for a white Christmas.

In August 1943, Sergeant Hollis Smith, in Port Moresby, New Guinea, penned a letter to his parents in Cove, Ark., urging them to spend the money he was sending home rather than keep it for his return. “I want you to finish paying off that place [the farm], and use all of it that you need,” he wrote. Smith would never know if they heeded his advice. On October 27, 1943, he and 11 other crewmen aboard the Consolidated B-24D Shack Rat crashed in the thick tropical rainforest of the Sarawaget Mountains in southeast New Guinea.

Part of the 320th Squadron, 90th Bombardment Group (the “Jolly Rogers”), Smith and his crewmates took off at 7:30 a.m. from 5-Mile Drome, an airfield outside Port Moresby, to observe and photograph enemy ships in the Bismarck Sea. At 2:30 p.m. V Bomber Command warned Shack Rat of bad weather at Port Moresby, ordering it to land instead at Dobodura. After acknowledging the order, the B-24 was never heard from again. U.S. Army Air Forces recovery teams launched multiple air searches along New Guinea’s east coast, but couldn’t find the crash site. In 1949 the Army Graves Registration declared the 12 airmen unrecoverable.

That’s how things stood until August 2003, when Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC) acquired a B-24 data plate and the ID card of Jack Volz, Shack Rat’s pilot, which a New Guinean had salvaged from wreckage in the mountains northwest of Dobodura. After two failed attempts to reach the crash site, in 2007 a JPAC recovery team spent three months there, then set to work contacting relatives and comparing DNA samples.

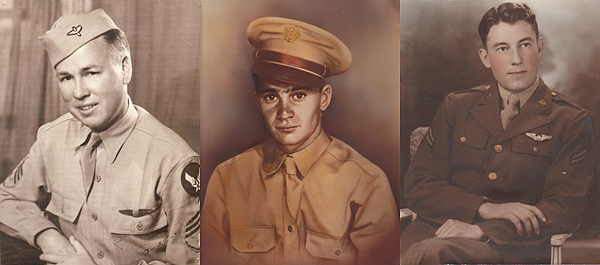

As of December 2010, the identified remains of three Shack Rat crewmen have been returned Stateside and buried with full military honors: engineer Hollis Smith in Cove; tail gunner Claude A. Ray in Riverside, Calif.; and photographer Claude Tyler in Arlington, Va. The remains of the airmen who could not be identified will be interred at a memorial in Arlington National Cemetery in May.

Before the fateful flight, Claude Ray wrote his parents that he hoped to return to Kansas for a white Christmas in 1943. With 297 service hours in B-24s, he needed just three more to complete his tour of duty, so he volunteered to serve on Shack Rat when its tail gunner got sick. For the rest of her life, Ray’s mother would leave the room whenever “White Christmas” was played on the radio.

Gayla Claborn, Smith’s niece, expressed her gratitude for the continuing efforts to repatriate fallen servicemen. “Our family was overwhelmed and amazed,” she said. “It is very encouraging to know that 67 years later the military would put forth the time, energy and resources to bring my uncle home.”