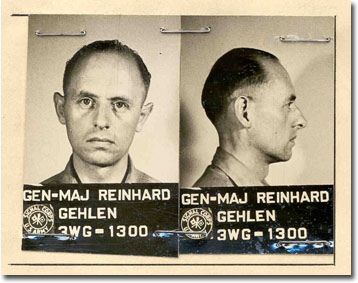

As Hitler’s Third Reich crumbled under the relentless pressure of the advancing Allies in May 1945, Reinhard Gehlen, the head of Nazi intelligence for the Eastern Front, saw the writing on the wall and grabbed his files.

As the old saying goes, if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em.

Gehlen had a trove of intelligence on the Soviets, which, according to his 1972 memoir, The Service, he hid in steel cases in Bavaria. Then, the former Nazi intelligence officer quickly surrendered to Counter Intelligence Corps of the U.S. Army.

He brokered a deal that instead of being prosecuted for war crimes, he and a select group of his men would establish a secret intelligence service for the occupation forces and hand over the service files they had on the Soviets.

With the Soviet threat looming—British Prime Minister Winston Churchill purportedly wanted to continue on and push toward the Soviet Union—it became apparent that the Americans were wholly unprepared for this emerging menace and agreed to work with the Nazi in order to glean intelligence.

So Gehlen did what he did best: spy.

Given autonomous command by the U.S. occupation forces, Gehlen personally chose his German staff to set up what was known as the “Gehlen Organization,” or “the Org” for short.

According to the Institute for Policy Studies, Gehlen proceeded to enlist thousands of Gestapo, Wehrmacht and SS veterans. Even the vilest of the vile–the senior bureaucrats who ran the central administrative apparatus of the Holocaust–were invited into the Org, including Alois Brunner, Adolf Eichmann’s chief deputy.

“It seems that in the Gehlen headquarters, one SS man paved the way for the next and Himmler’s elite were having happy reunion ceremonies,” the German newspaper the Frankfurter Rundschau reported in the early 1950s.

Returning to West Germany under the U.S. Army’s G-2 (Intelligence) branch in 1946, Gehlen and the Org were soon transferred, under the aegis of the CIA and bankrolled with millions of U.S. dollars.

The Org was primed for the onset of the Cold War in ways that the U.S. was not. It has been estimated, according to the Washington Post, that Gehlen “and the thousands whom he employed in his counterespionage organization provided this country’s Central Intelligence Agency and the Pentagon with 70 percent of its intelligence on the U.S.S.R. and Eastern Europe.”

This raw intelligence, however, blinded many within the CIA, allowing many of Gehlen’s men to maneuver and peddle data–much of it false or exaggerated–in return for cash and safety.

The Gehlen Organization had a vested interest in making the Cold War a lot colder.

It also had a vested interest in looking after its own, with many members within the Org playing an instrumental role in helping thousands of Nazis escape via “ratlines” to safe havens abroad.

More than 75 years after war’s end, debate still continued as to whether Gehlen himself was an ardent Nazi. According to a 2001 CIA affidavit, the organization stated that “General Gehlen himself is not considered an alleged Nazi war criminal.”

James H. Critchfield, a CIA officer assigned to the Gehlen organization from 1949 to 1956, told the Washington Post: “I’ve lived with this for 50 years. … Almost everything negative that has been written about Gehlen, in which he has been described as an ardent ex-Nazi, one of Hitler’s war criminals—this is all far from the fact.”

America’s eagerness for intelligence laid bare a mortal flaw: human greed.

“By bankrolling Gehlen,” writes the Institute for Policy Studies, “the CIA unknowingly laid itself open to manipulation by a foreign intelligence service that was riddled with Soviet spies. Gehlen’s habit of employing compromised ex-Nazis–and the CIA’s willingness to sanction this practice–enabled the USSR to penetrate West Germany’s secret service by blackmailing numerous agents.”

For the most part, however, Gehlen remained untouched by scandal, with his organization transforming into the present-day Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), the German counterpart to the CIA, in 1956. Gehlen retired in 1968 and lived in quiet retirement, protected by both the Americans and Germans until his death in 1979.

The German newspaper Der Spiegel noted decades after Gehlen’s death: “If there was ignorance on the matter, it was only because no one wanted to know.”