Faced with a rampant prostitution crisis in Nashville, the U.S. Army tried a bold social experiment

Even before the war, Nashville had a flourishing skin trade. The 1860 census counted 207 Nashville women admitting to prostitution as their livelihood—198 white and nine mulatto. The city fathers recognized they had a problem but were unable to agree on a solution. Thankfully, most of the trade was confined to bawdy houses; most of them were little better than two-room shanties known as cribs. Some abodes, however, were luxurious, probably catering to a higher class of clients. Best-of-the best was a house run by sisters Rebecca and Eliza Higgins. It was valued at $24,000 with 28 people, including 17 prostitutes, living there. Not far behind was Martha Reeder’s house. She had personal property valued at $15,000, making her one of the city’s wealthier citizens. Mag Seats’ house specialized in adolescent sex, but the typical Nashville prostitute was about 30, widowed, and had small children.

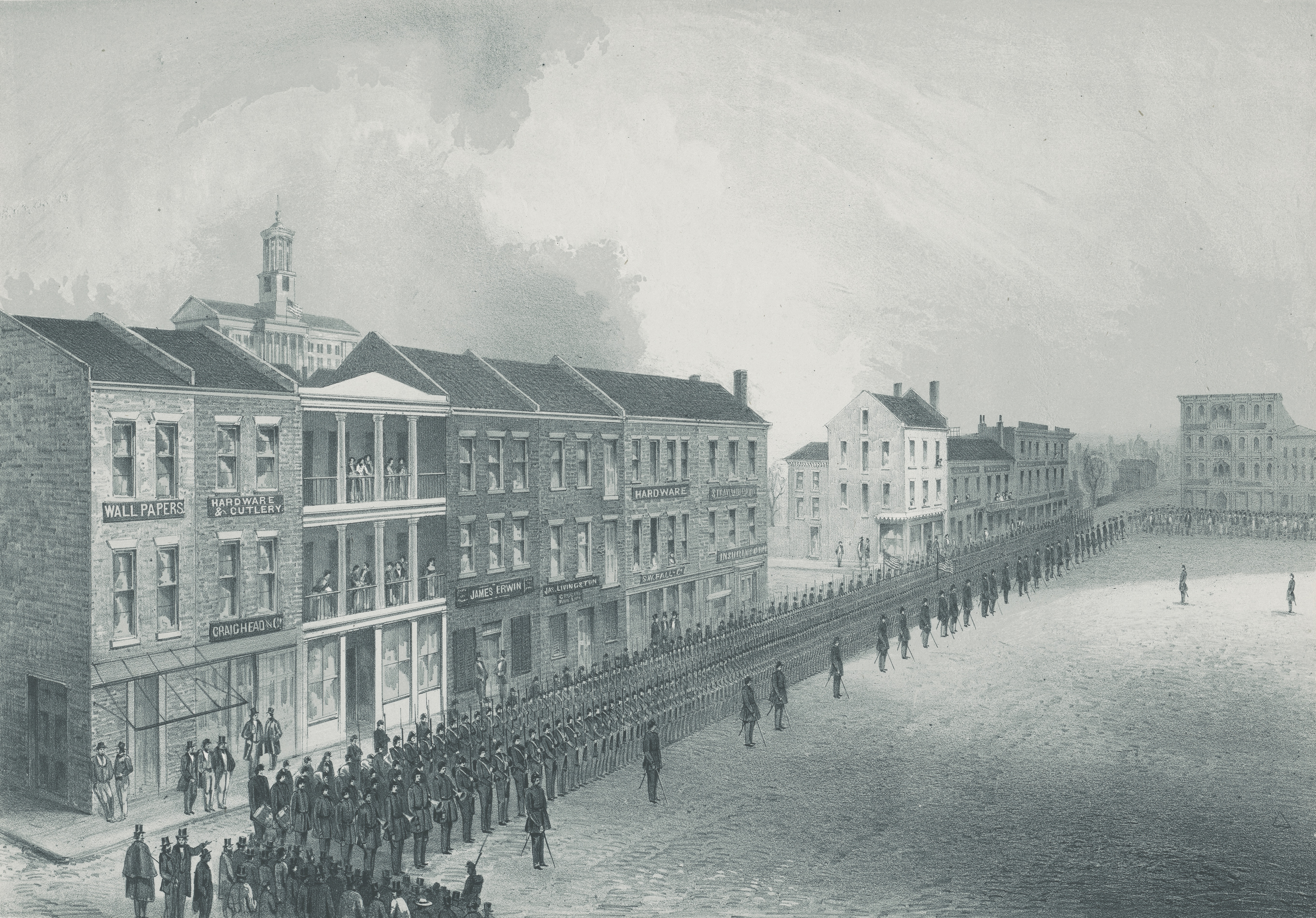

As the Union garrison swelled to more than 30,000, so did the number of prostitutes. By the summer of 1862, some estimated the number of “public women” in Nashville to number nearly 1,500, and they were always busy. While many were eager to relieve the soldiers of their money, most came out of desperation. Nashville offered them an environment safe from armed marauders, ample food at stable prices, and a chance to take care of themselves—and often their children—without benefit of a male provider. Nearly all of Nashville’s prostitutes were associated with a bordello; few plied their trade as individual street walkers. This gave many women from isolated rural farms their first experience of a supportive community of their peers.

Where prostitutes saw opportunity, civic leaders and military officials saw a growing problem. Benton E. Dubbs, an Ohio private, recalled a saying among the troops that no man could be a soldier unless he had passed through Smokey Row. Even with a burgeoning clientele, competition for customers was far from friendly. Nashville’s three newspapers regularly carried stories of internecine strife such as “Mattie Smith, Mary Morgan, Jane Morgan, and Alice Hoffman were fined $5 each for sending a crowd of soldiers to clear out Martha Carson’s house.” Or “Sally Mosely, Ada Wyatt, and Ellen Pinson sent a body of soldiers into Mary Morgan’s to ‘cut up and run around’ for which they were fined $5 each.” The Nashville Dispatch opined, “If the Provost Marshall would send a squad of his men down there some fine night and place in jail every man they find there, it would be a wholesome lesson to others to keep out of such company.”

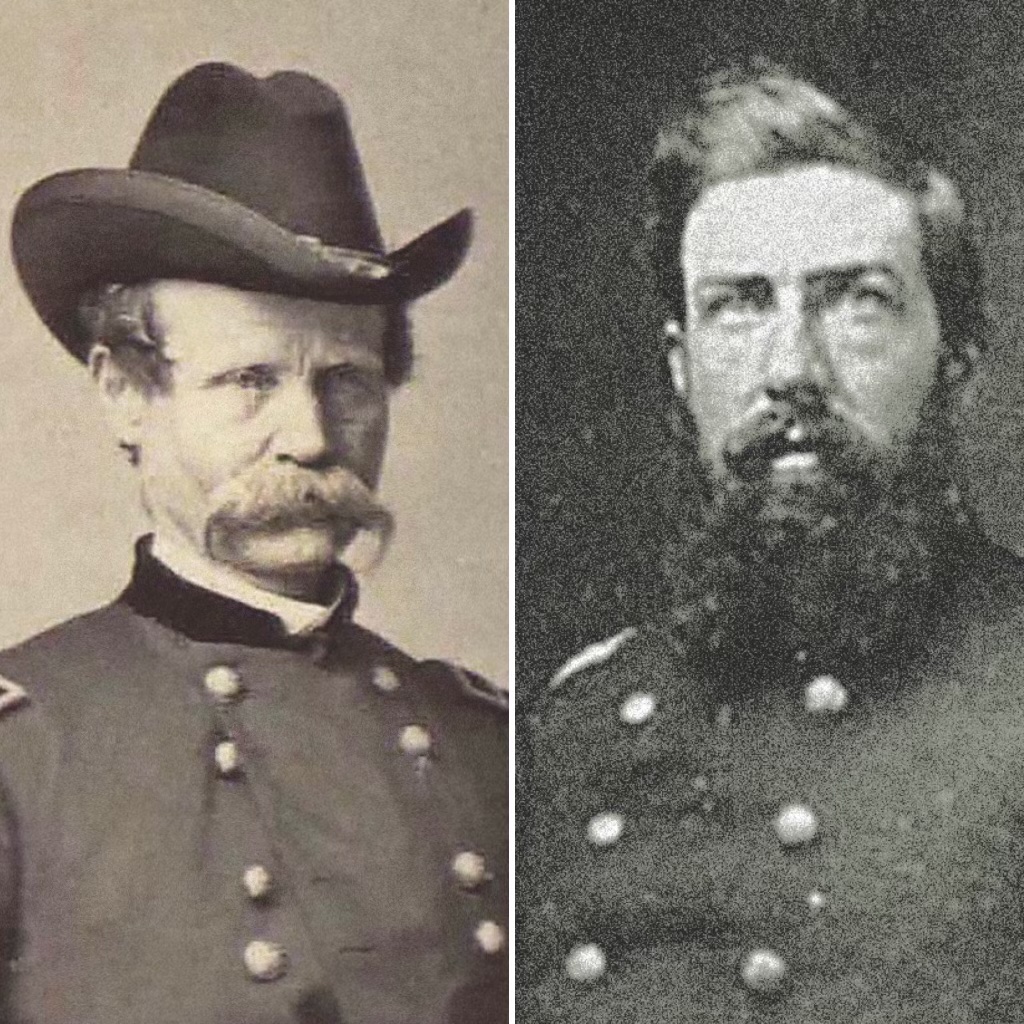

Brigadier General Robert S. Granger, the garrison commander, knew the provost guard couldn’t jail all the offending soldiers. But neither fines, threats of jail, nor appeals to moral conscience stemmed the flourishing trade. So Granger tried the Army way. He would round up the women and ship them out of town. The task fell to provost marshal Lt. Col. George Spalding of the 18th Michigan Infantry. In December 1862, Spalding’s men scooped up all the prostitutes they could—the exact number varies—and put them on a train for Louisville. But the women found far fewer prospective clients in the smaller garrison there and quickly made their way back to Nashville. By summertime, Nashville’s problem was getting worse and more obvious. As the temperature rose, the women of pleasure advertised by wearing fewer and fewer clothes.

So, on July 6, 1863, Granger issued Special Orders No. 29 authorizing Spalding “without loss of time to seize and transport to Louisville all prostitutes found in this city or known to be here….” The Nashville Dispatch reported “General Granger has given notice to a large number of women of the town that they must prepare to leave Nashville. It is said they are demoralizing the army and that their removal is a military necessity.” Spalding again led soldiers and police officers on raids of the city’s brothels, “heaping furniture out of the various dens, and then tumbling their disconsolate owners after.” The roundup lasted all month. But, having failed by rail, Spalding now included the river as an additional avenue of expulsion.

That decision was bad news for John Newcomb. As captain of the Idahoe, a new side-wheeled steamer chartered to the army, he hoped to take advantage of lucrative contracts hauling military cargo. But Newcomb couldn’t have expected that his first consignment order would read, “You are hereby directed to proceed to Louisville, Kentucky, with the 100 passengers put on board your steamer today, allowing none to leave the Boat before reaching Louisville.” The Dispatch reported “a boat was chartered by the government for the especial service of deporting the ‘sinful fair’ to a point where they can exert less mischief….” Newcomb protested but to no avail and the Idahoe would henceforth be known as “The Floating Whorehouse.”

Newcomb and the Idahoe began their fateful voyage north on July 8. Again, the exact number of passengers varies. When the Idahoe reached Louisville, it was met at the wharves by armed guards. Ordered to sail on, Newcomb continued up the Ohio River, finally docking at Cincinnati on July 17. The city fathers there had heard the Idahoe was coming and what it was carrying. They, too, pulled up the welcome mat. Reported the Cincinnati Daily Gazette, “The Idahoe came up, bringing a cargo of 150 of the frail sisterhood of Nashville, who had been sent north by military orders. There does not seem to be much desire on the part of our authorities to welcome such a large addition to the already over-flowing numbers engaged in their peculiar profession….”

Newcomb became desperate; he was out of provisions and his ship was being destroyed by his unhappy and increasingly unruly passengers. For two weeks, the Idahoe bobbed in limbo while Newcomb frantically telegraphed Washington, D.C., for instructions. The matter came before Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton who ordered the ill-fated ship back to Nashville. The Dispatch reported that crowds of people gathered at the wharf, jostling each other “for the purpose of looking at the steamer which carried out and brought back the precious freight.” By August 5, the voyage of the damned was back where it started, the women went back to work, and the army had an even bigger problem on its hands.

It seems that while their white sisters were embarked on their riverine odyssey, black women surged into Nashville to meet the continuing demand for paid pleasure. The Nashville Daily Press thundered, “Unless the aggravated curse of lechery as it exists among the negresses of this town is destroyed by rigid military or civil mandates, or the indiscriminate expulsion of the guilty sex, the ejectment of the white class will turn out to have been productive of the sin it was intended to eradicate….No city…has been more shamefully abused by the conduct of its unchaste female population, white or black, than has Nashville…for the past eighteen months….We trust that, while in the humor of ridding our town of libidinous white women, General Granger will dispose of the hundreds of black ones who are making our fair city a Gomorrah.”

Now under intense pressure from his superiors, the ever resourceful Lt. Col. Spalding seemingly had an epiphany. Drawing on the strict Presbyterian discipline he learned as a child, Spalding decided if he couldn’t defeat the women, he would legalize them. And so began the army’s unprecedented program to turn a civic vice into a public virtue benefiting the citizens of Nashville, the soldiers garrisoning the city, and the women

who plied a trade that defied eradication.

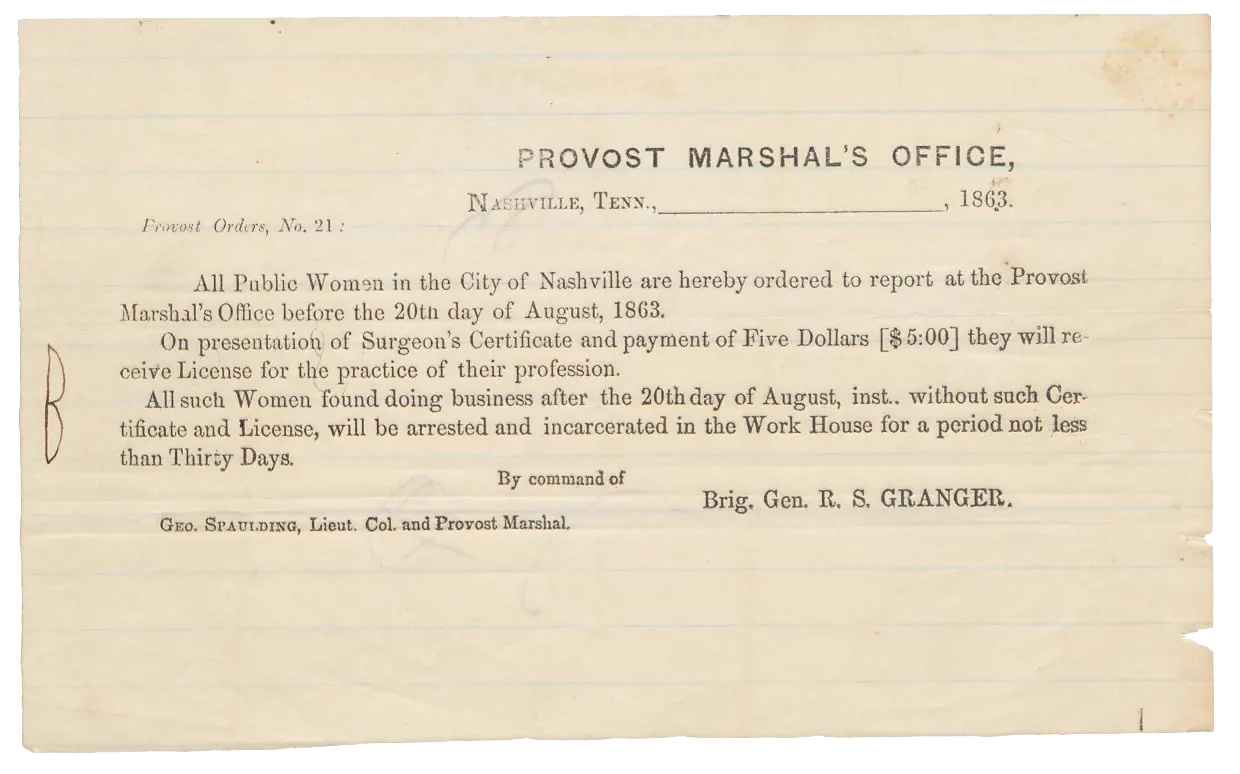

Desperate for anything that might alleviate the growing clamor for action, Granger quickly approved Spalding’s plan. It had four parts. First, each prostitute would be issued a license costing $5 and have her address recorded by the provost authorities. Second, an army surgeon would give each woman a medical examination; only healthy women would be certified to practice their trade legally. Certificates would cost 50 cents per visit; it would soon be raised to $1. Third, diseased women would be sent to a special hospital reserved for their treatment and pay a 50-cent weekly tax for its upkeep. Finally, any woman found practicing her trade without a health certificate was subject to incarceration in the workhouse for 30 days. All “public women” were told to report for examination by August 17 or face 30 days in the city jail.

On May 4, 1864, Captain Thomas Taylor of the 47th Ohio Infantry wrote in his diary, “Gay time—dinner at Carr City—Much whiskey—plenty of spirit, little wit, and less sense. Reached Nashville little before sundown and stopped at City Hotel—visited College Street.” The reference to “College Street” is interesting, as that thoroughfare was in the midst of “Smokey Row,” Nashville’s red light district, and it is possible Taylor was making an allusion to frequenting a prostitute. Of course, he might have gone down there to have a meal and a drink…but that certainly wasn’t the primary reason most soldiers “visited” that section of town. –D.B.S.

At first, prostitutes were required to report to the surgeon’s office every fortnight, but Dr. William M. Chambers, head of the Board of Examination, soon required check-ups every 10 days in order to treat infectious sex workers more promptly. In his January 31, 1865, report, Chambers described how the procedure worked. The prostitutes “enter a reception room which is comfortably furnished and in cold or disagreeable weather well heated. They pass in time from this apartment into an adjoining examination room in which there are a bed, a table, and all the necessary appliances for examining them.” Women who passed the exam received certificates and a figurative public seal of approval. Those not certified were promptly hospitalized.

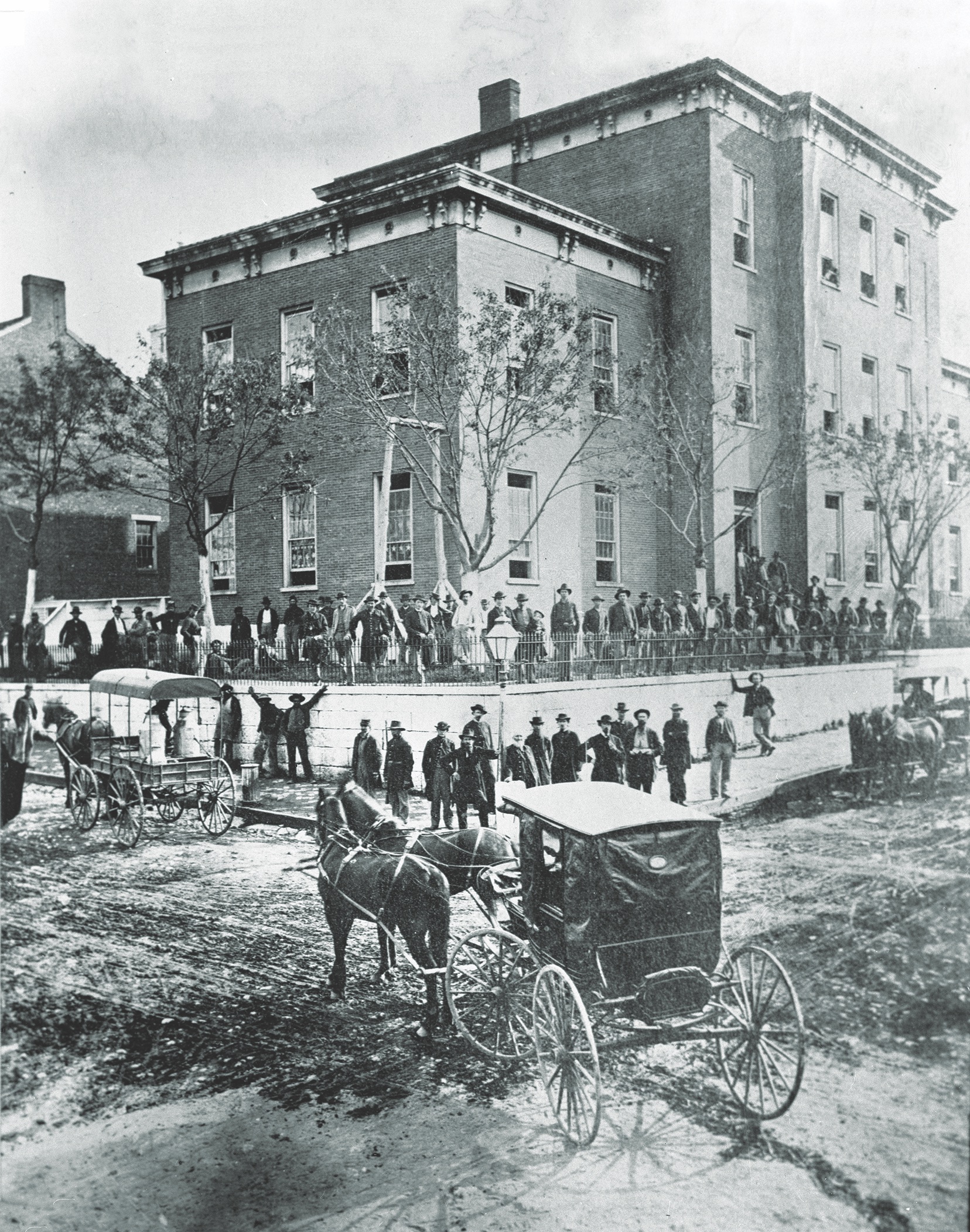

The Union Army operated 23 hospitals in Nashville. Hospital No. 11, a sturdy brick building on North Market Street that ironically had once been the residence of the Catholic bishop of Nashville, became the “Female Venereal Hospital” also known as “The Pest House.” It had a comfortably furnished living room paid for by examination fees, a treatment room, and two wards of 10 beds each. Black female matrons recruited from the nearby contraband camp did the cooking and a black man was hired to do any necessary manual labor.

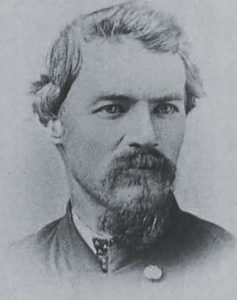

Armed guards prevented anyone from entering the premises unless accompanied by the resident physician, Dr. Robert Fletcher of the U.S. Volunteers. Appraising the hastily devised program a year after its inception, Dr. Fletcher concluded “after the attempt to reduce disease by forcible expulsion of prostitutes had, as it always had, utterly failed, the more philosophic plan of recognizing and controlling an ineradicable evil has met with undoubted success.”

The numbers support Dr. Fletcher’s conclusion. By the end of the first week, the provost marshal’s report showed 123 women examined and licensed. Twelve women were admitted to the hospital during the first month of operation; 28 more during the following two months. By January 1864, licensed prostitutes numbered 352, 60 of whom were diseased and admitted to the hospital. By August 1864, the number had risen to 456 and officials expanded the registration program to include 50 black prostitutes. By the end of January 1865, the Female Venereal Hospital had treated 207 women. Patients were not allowed to leave until “perfectly cured;” then they were allowed to “return to duty.” Dr. Chambers also made house calls for an additional fee of one dollar.

The Nashville experiment also seemed to refine the appearance and conduct of the women. “When the inspections were first enforced many [prostitutes] were exceedingly filthy in their persons and apparel and obscene and coarse in their language,” Dr. Fletcher reported, “but this soon gave place to cleanliness and propriety.” Dr. Chambers observed that many prostitutes “gladly exhibit to their visitors the ‘certificate’ when it is asked for….” Military officials attributed some of the increasing number of registered prostitutes and those seeking treatment to the popularity of Spalding’s order. In fact, they ascribed part of the increasing number of registered prostitutes to an influx of women from other areas who learned that conditions in Nashville were safer and healthier. Civilian authorities raised little opposition to the program. As proof, the city council voted to defer all regulation and enforcement of what was now a legal part of Nashville’s civic life to the military authorities.

But what about the soldiers? Spalding’s regulations were enacted primarily to improve the health and unit preparedness of the garrison. In February 1864, Hospital No. 15, a three-story brick building on Line Street, was converted into a facility for soldiers’ venereal cases only. Surgeons at the 140 bed facility admitted more than 2,300 cases by the end of the year, but only 30 had been infected while in Nashville. It seems that a large number of veterans returning from home leave or reenlistment came through town during that same period and brought their afflictions with them. Dr. Fletcher acknowledged that the cooperation of the garrison’s officers was vital to the program’s success, writing “When a soldier of the post forces is infected, it is not uncommon for his captain to report the case, with the name of the suspected woman, who is immediately arrested and examined.” Of course, officers themselves were not immune to the allure of illicit flesh. Before Spalding’s edict went into effect, 20-30 officers per month were treated for venereal diseases; after, the number dropped to one or two.

The end of the war brought an end to Nashville’s bold social experiment. The regiments garrisoned there dispersed and mustered out. Colonel Spalding returned to Michigan where he served as postmaster and mayor of Monroe, studied law, and served two terms in Congress from 1895-1899. He died in 1907. Dr. Fletcher went to Washington, D.C., where he wrote and edited numerous medical publications for the Office of the Surgeon General. He also made significant contributions to the study of anthropology and the history of medicine. He died in 1912. William Chambers returned to Charleston, Ill., and practiced medicine there until he died in 1892.

It took two years for John Newcomb, captain of the star-crossed Idahoe, to receive about $5,000 from the Treasury Department for damages to his ship and expenses he incurred while transporting his human cargo. And what of the women of Nashville, without whom this most unusual medical experiment would not have been possible? They disappeared into history’s shadows, unknown and unrecognized.

Frequent Civil War Times contributor Gordon Berg writes from Gaithersburg, Md.