At 7:05 on the morning of March 19, 1945, the aircraft carrier USS Hancock broadcast a sighting of an unidentified twin-engine aircraft to the ships of Task Force 58, positioned for attack southwest of Japan. A minute later the Hancock reported again to the group, “Bogie by Hancock 350 distance 10.” Three minutes later it broadcast directly to the nearby carrier USS Franklin: “Bogie closing you!” That last report never made it to the bridge, and the Franklin’s captain never called his crew to battle stations. A Japanese dive-bomber broke from the clouds at 2,000 feet about 1,000 yards off the Franklin’s bow. On the bridge the navigator, Commander Stephen Jurika, heard the ship’s forward 5-inch antiaircraft guns fire, and saw two bombs hurtling from the sky.

With terrible precision, the two 550-pound semi-armor-piercing bombs plunged through the Franklin’s deck. The first struck next to the island on the starboard side of the ship. The second landed aft, among the collected planes loaded for war. Planes toppled over one another; propellers cut wings, cut tails. Everything was on fire.

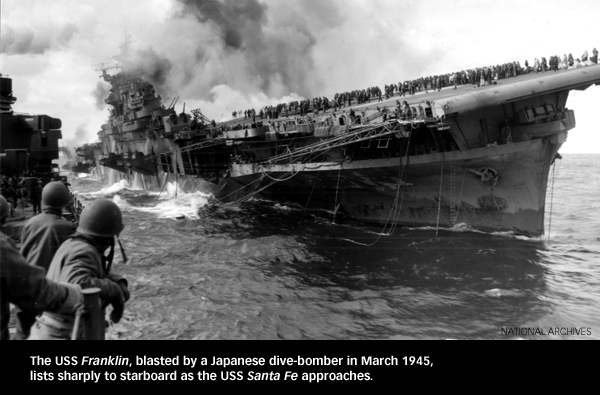

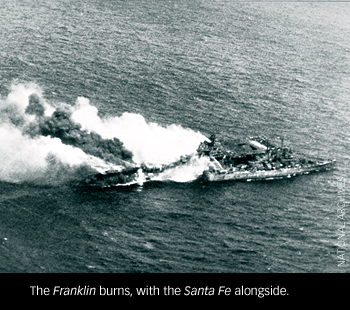

It was a direct hit. Almost immediately, “the entire ship was wreathed in choking smoke,” as Jurika later recalled. The Franklin listed sharply to its starboard side. Surely, observers on nearby ships thought, it would soon slip beneath the waves. Instead, this mayhem set the stage for one of the most heroic naval rescues in modern history.

The day before the attack had been a noteworthy one for the Franklin: March 18 marked its return to combat after being seriously damaged in a kamikaze attack the previous October. Following a Christmas of major repairs in Puget Sound, the Essex-class carrier—the namesake of four previous ships honoring Benjamin Franklin, and known by its crew as Big Ben—had returned to the fleet earlier that month with new planes, many new men, and a new captain.

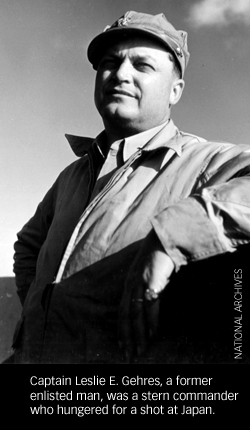

Captain Leslie E. Gehres was a big man—six feet five—loud and direct, an aviator and a World War I veteran. He had spent most of the war in the Aleutians, where men had nicknamed him Custer for his aggressive air wing tactics and what many thought was erratic behavior. The 47-year-old Gehres was the navy’s first aviation commodore when he took a step down in rank to command the Franklin. This was his shot at Japan, the shot he often talked about, the shot he hungered for.

Four days earlier, the Franklin had set out with Task Force 58 from its sunny anchorage in Ulithi. Now, as the more than 120 American warships spread across 50 square miles of sea southwest of Japan, the water was dark and gray. Clouds hung heavy and low. Stiff winter winds cut across the decks; slurries of snow and rain raged around them. Below deck men dug winter gear out of long-unused lockers. They were bundled in layers: two, three pairs of pants; sweaters from home; knit hats pulled low under helmets; collars pulled high over exposed skin.

Four days earlier, the Franklin had set out with Task Force 58 from its sunny anchorage in Ulithi. Now, as the more than 120 American warships spread across 50 square miles of sea southwest of Japan, the water was dark and gray. Clouds hung heavy and low. Stiff winter winds cut across the decks; slurries of snow and rain raged around them. Below deck men dug winter gear out of long-unused lockers. They were bundled in layers: two, three pairs of pants; sweaters from home; knit hats pulled low under helmets; collars pulled high over exposed skin.

Visibility had been reduced from several dozen miles to a mere seven. It was weather the captain of one of the battle cruisers called “ideal for single-plane sneak attacks on our forces.” That morning, the task force had begun striking the Japanese home islands to knock out enemy air power before the invasion of Okinawa. Now Japanese retaliation was underway—which made for an anxious evening at sea.

The crew aboard Big Ben had been called to battle stations 12 times within six hours that night. By the morning of the 19th, the men were exhausted. With the radar screen blank, Gehres downgraded the alert status to Condition III, leaving his men free to eat or sleep, although gunnery crews remained at their stations.

A tired calm swept over the ship. Word circulated among the navy and marine aviators of the Franklin’s air group that scouts had found the Japanese supership Yamato, the largest battleship ever built, well within striking distance. On the hangar deck crews casually fueled planes and switched out general ordnance for armor-piercing bombs. The pilots mingled into the line of men that wound out of the third deck galley and through the hangar. More than 200 men had gathered there to wait for breakfast—their first hot meal in two days.

Then the bombs screamed down. On the fantail, the blast threw the Franklin’s executive officer, Commander Joe Taylor, 100 feet. In the warrant officers’ mess someone yelled, “We’ve been hit!” Kansas City Star correspondent Alvin S. McCoy, who had just gone below deck to the mess for breakfast, watched “men’s faces…turn pale.” In the wardroom the Catholic chaplain, Lieutenant Commander Joseph O’Callahan, was making a joke about the day’s breakfast fare of French toast—“fried bread,” he called it—when the blast bowled him over. On the bridge, men were knocked off their feet. Gehres scrambled up and saw a great flame rip under the flight deck, out the hangar deck, and spread starboard.

“I immediately ordered the ship turned to starboard and speed slowed to two-thirds,” Gehres later wrote in his report on the bombing. The maneuver was intended to clear the ship of smoke. But as the ship turned, smoke rolled back over the bridge and the Franklin steamed straight at the light carrier Bataan. The smoke cleared just enough, the Bataan corrected, and the ships passed within a few hundred yards of each other.

Taylor meanwhile pulled himself forward from the fantail to the hangar deck on netting hung on the starboard side. He crossed out of the smoke to the port side, then crawled back starboard, following the seams in the deck. The ship turned, the smoke moved, and Taylor saw his entrance into the island and an emergency ladder to the bridge. “Joe,” Gehres teased as he arrived, “your face is dirty as Hell.” The attempt at levity put Taylor at ease.

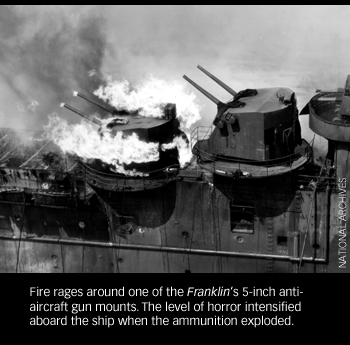

Then the men got a more convincing glimpse of hell. The Franklin’s arsenal of weapons began detonating as the fire spread to the bombs and planes and stores of ammunition. “Large numbers of men and a considerable number of officers and chief petty officers were blown over the side aft of the island or forced off aft when faced with a choice of going overboard or being burned to death,” Gehres recalled. The intense heat melted the electric wires and knocked out nearly all lines of communication.

“Fifty-caliber ammunition in the planes on the deck set up a staccato chattering,” Jurika recalled, “and the air was well punctuated with streaks of tracer.” The blasts, in his words, “were soul-shaking.” Explosions and raging flames worked over the flight deck and its torpedo planes and fighters, fully loaded with aviation fuel, bombs, ammunition, and rockets known as Tiny Tims. New to the armory, Tiny Tims were anything but small: each rocket was more than 10 feet long and almost 12 inches in diameter, with a 500-pound ship-busting warhead. They caught fire on the Franklin’s deck and zipped off—port, starboard, forward, aft, up, down, straightaway, and end over end. Taylor called the sight of the rockets whooshing by in close proximity “one of the most awful spectacles a human has ever been privileged to see.”

Smoke and heat and fire spread throughout the ship. A three-inch fuel line ruptured and sprayed. The gasoline pump room flooded with fuel, which spilled free and flooded the hangar deck, fanning the flames. Crews tried to wet down the ready-service magazines—but there was no water pressure. They spun the valves to flood the magazines below deck so the hundreds of tons of ordinance there wouldn’t blow, unaware that no water was reaching them. Other men scrambled to toss live rounds over the side; many were blown over the side themselves.

Smoke and heat and fire spread throughout the ship. A three-inch fuel line ruptured and sprayed. The gasoline pump room flooded with fuel, which spilled free and flooded the hangar deck, fanning the flames. Crews tried to wet down the ready-service magazines—but there was no water pressure. They spun the valves to flood the magazines below deck so the hundreds of tons of ordinance there wouldn’t blow, unaware that no water was reaching them. Other men scrambled to toss live rounds over the side; many were blown over the side themselves.

At about 7:30 a.m. Rear Admiral Ralph Davison, the commander of the Franklin’s task group, made it to the bridge along with his staff. The Franklin was Davison’s flagship, but now he told Gehres, “Captain, I think there’s no hope.” Davison intended to transfer his flag to the Hancock. According to the quartermaster on watch, John O’Donovan, who recounted the scene to A. A. Hoehling in The Franklin Comes Home, Gehres nodded and said nothing.

“I think you should consider abandoning ship—those fires seem to be out of control,” the admiral continued. Once more, Gehres nodded, saying nothing. With that, they shook hands, wished each other luck, and Admiral Davison left the bridge.

An admiral isn’t in charge of any one ship, but the coordination of many ships. Decisions on the operation of a fighting ship, decisions such as whether to abandon ship, rest with the captain and the captain alone. Gehres would later say that he was reluctant to give the “abandon ship” order because he was aware that there were many men trapped alive below deck. Critics would claim that Gehres was more mindful of the carrier captains who had lost their ships, never to command a carrier again.

The destroyer Miller came alongside to collect the admiral, and trained four water jets on the Franklin’s fires. A light cruiser, the Santa Fe, hung 100 feet off the starboard side, waiting to remove the wounded that were gathering on the front end of the ship. Admiral Davison transferred to the Miller by breeches buoy on a high wire—an undignified sight, suspended between ships by the seat of his pants. “Am afraid we’ll have to abandon her,” he broadcast from the Miller to Vice Admiral Marc Mitscher, who was leading the task force from the carrier Bunker Hill. “Please render all possible assistance.”

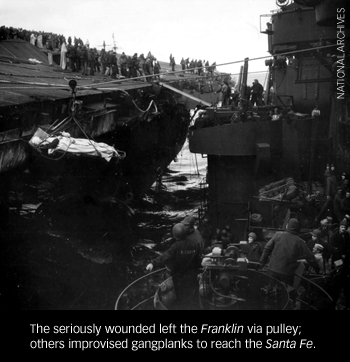

As the Miller steamed away, the Santa Fe pulled along the Franklin’s starboard side. The two ships came together shortly after 9:30 a.m. Messenger lines were shot across from the Santa Fe, and the injured were moved with trolley lines and across a downed radio antenna. At about this time Gehres received reports that men working in the ship’s fire and engine rooms were collapsing. They were ordered to stay as long as possible before moving to safer ground, and then to leave everything set and running. More men collected forward, on the deck, in the forecastle. Finally, the remaining men in the engine and steering rooms fled the heat. By 10 a.m., the Franklin lay dead in the water—just 52 miles off the coast of Shikoku, Japan, and drifting ever closer.

Once the Franklin lost its steam, it was impossible for the Santa Fe to maintain the connection. The big carrier was at the whim of the sea and the lines of the light cruiser snapped free. “This was an unhappy moment for our hundreds of seriously wounded men,” Father O’Callahan later wrote. “It hurt to look into their eyes.”

Below deck a chief boatswain broke into the warrant officer’s mess. The journalist McCoy and others who had been trapped in that compartment since the first bomb fell made their way topside. There, they could see destroyers massed in the Franklin’s wake, picking up the living and the dead from the cold, dark sea. McCoy later wrote that hundreds of men drifted for miles in the water behind Big Ben. One sailor, afraid to jump, tried to shimmy down a line. When the line tangled around his leg, the sailor lost his grip and dangled upside down over the side of the Franklin, his head submerging with the roll of the ship, under then out, under then out as the ship bobbed up and down. The dead man hung there, a horrific sight that men on the destroyers and in the sea would never forget.

The Santa Fe’s Captain Harold C. Fitz moved the cruiser in again, fast. Men on the bridge braced for a collision. Fitz cut the wheel and ordered the engines full astern. The cruiser swung parallel to the carrier and then slammed into its side, where, Gehres recalled, “she was held by her commanding officer by use of the engines.” Gehres would say that was the best example of ship handling he had ever seen.

The Santa Fe’s Captain Harold C. Fitz moved the cruiser in again, fast. Men on the bridge braced for a collision. Fitz cut the wheel and ordered the engines full astern. The cruiser swung parallel to the carrier and then slammed into its side, where, Gehres recalled, “she was held by her commanding officer by use of the engines.” Gehres would say that was the best example of ship handling he had ever seen.

But before they could begin offloading the wounded, the level of horror suddenly intensified when the ammunition for the aft 5-inch antiaircraft guns exploded. “Whole aircraft engines with propellers attached, debris of all description, including pieces of human bodies were flung high into the air and descended on the general area like hail on a roof,” Jurika recalled.

Dozens of sailors huddled together on the bow, terrified, unsure of where to go or what to do. As the Santa Fe ground against the Franklin, the wounded were transferred to the cruiser, followed by the air group personnel and then, per Gehres’s orders, men not essential to beating down the flames and running the ship.

A handful of well-meaning junior officers passed out clothing—officers’ clothing—to enlisted men soaked through with saltwater. This drove others to loot for more dry clothes and gear. Young men in admiral life jackets and commander coats crossed to the Santa Fe. Enlisted men watched these “officers” leave, which escalated the confusion aboard ship. Had the captain ordered abandon ship? Yes, some said. No, said others. Command broke down. Men on the open deck jumped into the water. Others shimmied across the downed radio antennas to the Santa Fe.

“Concerned for the men huddling forward, I asked my navigator, Commander Jurika, if he thought I should permit them to leave to the safety of the Santa Fe,” Gehres later recounted. “He replied that he did not think it was time yet, and the young officer of the deck, Lieutenant Tappen, said nothing but emphatically shook his head. With this support for my own convictions, the Santa Fe was informed that all wounded had been transferred, that no more Franklin personnel were to come aboard, and she was requested to clear the side, which she did at about 1225. This was the only time when anything resembling abandoning the ship was mentioned on the bridge.”

Below deck, Joe Taylor worked aft, through the officers’ quarters to the hangar deck. “Bodies were everywhere, in the passageways, on the ladders where they had dropped, one hanging from the catwalk on the overhead by one arm,” he recalled. The men who had stood in line for breakfast were charred in place. The early blasts rippled the gallery deck floor like the snap of a belt, and floor met ceiling—“deck heave,” they called it. Men were crushed and broken in between.

A marine pilot, Lieutenant Budd Faught, was one of four to survive in ready room no. 51 on the gallery deck—the half deck between the massive hangar and topside flight deck. Faught had been standing by the bulkhead trying to memorize the navigation maps for that day’s flight with First Lieutenant John Vandergrift. The bulkhead protected them as the deck contorted. Twenty-four others there had been instantly killed; Faught and Vandergrift got out with four broken legs and a broken arm between them. They crawled out of the carnage, over bodies and debris, to a deck rail, where Faught’s flight suit was manually inflated. Fires at their back, the two men tumbled off the ship, into the sea.

Deep in the ship, in a messing compartment on the third deck, air surgeon Dr. Jim Fuelling and Lieutenant (junior grade) Donald Gary were trapped with 300 men. As panic among the men swelled, the doctor reminded them to conserve energy and air, to stay quiet, to pray. They had been trapped all morning, the four exits blocked by smoke and flame. An explosion rocked the ship, and panic won out.

“We’re not dead yet!” Gary yelled. An engineering officer, he knew the turns and twists of the Franklin’s passages and had a rescue breather with him. He set off through 600 feet of smoke-filled space. He found another oxygen bottle and worked his way down to the fourth deck, then up an air shaft to fresh topside air. It took Gary three trips to clear the men from the compartment and lead them topside, linked in a chain, hand in hand or hand to belt, through the smoke and into the sun.

With Gehres’s stout refusal to abandon ship, efforts were begun to save it. As Davison and the remainder of Task Force 58 kept pounding Japan, Mitscher sent a single heavy cruiser, the Pittsburgh, to join the Santa Fe in aiding the wounded carrier. Just after 1 p.m. the Pittsburgh shot a messenger line attached to a towline over to the Franklin. After much struggle, the carrier was under tow. The Pittsburgh worked the Franklin around on a southerly course, back toward Ulithi and away from danger.

As the sun went down that day, the explosions reduced in frequency and ferocity; the fires calmed. Bread from the Santa Fe was passed out—half a slice per man, with a dollop of bacon fat. Crews worked into the night. By 9 p.m. a damage control party broke through the flames to boiler no. 5; by 10:30 it was lit and running. The battle cruisers Alaska and Guam were detached from combat duty to provide cover for the Franklin and take on the wounded. “It was an extremely comforting sight at daybreak,” Jurika wrote, “to find ourselves surrounded by many ships, including Guam and Alaska, Pittsburgh, Santa Fe and several destroyers.”

The Franklin’s engines turned a slow 56 rpm and the tow speed increased to six knots, but the ship’s pronounced list made steering next to impossible. “Franklin persisted in sheering up to port and sailing windward, dragging the Pittsburgh’s stern around,” Gehres recalled. When four boilers started running, things improved, and by 12:30 p.m. on March 20, the carrier cast off the tow. Within two hours the Franklin was making 15 knots, moving toward Ulithi under its own steam.

Around that time several bogeys put in an appearance. By 2:20 p.m., the Alaska picked up a plane 52 miles north. A second was reported a little further out six minutes later. The task force’s combat air patrol came in to intercept, but the fighters were mistaken for the bogeys on the radar screen and a Japanese D4Y Suisei (Comet) dive-bomber snuck through. The plane, using the sun as cover, wasn’t positively identified until it dived toward the Franklin. “Nothing but bad marksmanship on the part of the Jap pilot caused the bomb to fall 100 feet or so astern of the carrier,” the Alaska’s commander recalled.

Aboard the Franklin, all but a handful of fires were out. The forward 5-inch and two 40mm guns were up and running. Telephone communication between the bridge and those guns had been restored. Three hundred men and one hundred officers then faced a grisly task: “to extricate the hundreds of bodies tangled in the interior wreckage of the ship,” as Gehres recalled. Bodies were strewn everywhere, but no place was worse than the gallery deck. Gehres called it “a death trap.” It had pulled in flames from other areas and took the brunt of explosions above and below it. The thin metal decks and ceilings heaved and collapsed. The corpsmen on the gallery and hangar decks, the dressing station crew, were wiped out. Below deck men had died an air-starved death. In the sickbay, men without breathers succumbed to asphyxiation.

Aboard the Franklin, all but a handful of fires were out. The forward 5-inch and two 40mm guns were up and running. Telephone communication between the bridge and those guns had been restored. Three hundred men and one hundred officers then faced a grisly task: “to extricate the hundreds of bodies tangled in the interior wreckage of the ship,” as Gehres recalled. Bodies were strewn everywhere, but no place was worse than the gallery deck. Gehres called it “a death trap.” It had pulled in flames from other areas and took the brunt of explosions above and below it. The thin metal decks and ceilings heaved and collapsed. The corpsmen on the gallery and hangar decks, the dressing station crew, were wiped out. Below deck men had died an air-starved death. In the sickbay, men without breathers succumbed to asphyxiation.

Seven hundred ninety-eight men were killed aboard the ship, or died shortly thereafter of their wounds, and another four hundred eighty-seven had been wounded—the most casualties at that time of any ship in U.S. naval history except the Arizona at Pearl Harbor.

Although the exact toll took time to tabulate, its scale was painfully obvious to the men who remained aboard ship. In burials at sea, according to navy custom, men are sewn into canvas bags, with a weight—often a shell—between their legs. The last stitch, according to maritime lore, is always through the nose. But the Franklin was without bags or shells. Under a tattered American flag, in ceremonies that spanned day after day on the sad, slow steam home, each body was laid on a spare wooden board, prayed over, blessed, and tipped into the sea, where it floated in the wake until time and tide took it under.

Over the next month, Big Ben would go from Ulithi to Pearl Harbor, and from there through the Panama Canal to the Brooklyn Navy Yard for repair. But a final blow still awaited some of Big Ben’s survivors, delivered, ironically, by the captain of the ship himself. En route to Ulithi, Gehres had requested that the Santa Fe return about 100 men—men in positions he deemed necessary to running the ship. When the men rejoined the Franklin in Ulithi, Joe Taylor met them on deck and handed them a curtly worded letter from Gehres demanding a written explanation for why “you able bodied and uninjured left this vessel while she was in action and seriously damaged when no order had been issued to abandon ship,” as Joseph Springer recounts in Inferno: The Epic Life and Death Struggle of the USS Franklin in World War II.

Men who were blown out of their gun tubs or had jumped off the fantail with fire at their backs were furious. Gehres worsened the blow later in the journey when he handed out cards reading “Big Ben 704 Club.” The cards went only to the men who were aboard throughout the entire ordeal. Gehres promised charges and courts-martial for the other “deserters.” Navy brass never processed the charges; that decision was made, according to one legend, after a litigator floated the idea of accusing Admiral Davison, on Gehres’s logic, of desertion too. The Franklin men stood divided on Gehres—a strong-willed captain or a career-obsessed egomaniac—until the end.

The navy brass were not so conflicted. Captain Leslie E. Gehres was awarded the Navy Cross along with 18 other men, including the executive officer, Commander Joe Taylor, and the navigator, Commander Stephen Jurika. Silver Stars went to 22 men, 115 earned Bronze Stars, and 234 received Letters of Commendation. Two men, Father Joseph O’Callahan and Lieutenant (junior grade) Donald Gary, received the Medal of Honor.

The men who were not in the 704 Club didn’t receive so much as a handshake. Many lingered in limbo in Hawaii only to be redeployed to combat ships, never to see Big Ben again. The carrier itself was finished. By the time the Franklin was repaired, the war had ended, and in 1947 the ship was mothballed at Bayonne, New Jersey. The most damaged American warship ever to make its way home under its own steam at long last arrived at the end of its journey in 1966, when Big Ben was sold for scrap to the Portsmouth Salvage Company in Chesapeake, Virginia.

The men who were not in the 704 Club didn’t receive so much as a handshake. Many lingered in limbo in Hawaii only to be redeployed to combat ships, never to see Big Ben again. The carrier itself was finished. By the time the Franklin was repaired, the war had ended, and in 1947 the ship was mothballed at Bayonne, New Jersey. The most damaged American warship ever to make its way home under its own steam at long last arrived at the end of its journey in 1966, when Big Ben was sold for scrap to the Portsmouth Salvage Company in Chesapeake, Virginia.

Michael R. Shea has worked as a newspaper reporter in South Carolina and California and has earned several state and national journalism awards.