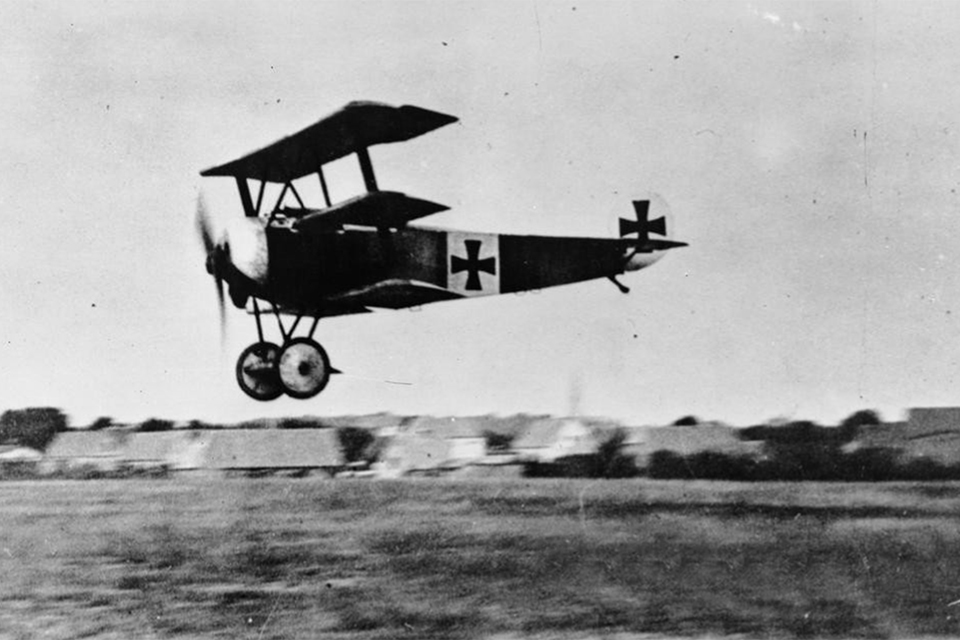

It is the most romanticized image in air combat history: a scarlet triplane, piloted by the notorious Red Baron, plucking another Allied aircraft from the burning French skies of World War 1, adding it to the long list of kills that made him the original ace of aces, with 80 confirmed air victories. The truth about Germany’s World War I hero lives up to the legend, although it took most of the war before this famed sight became a reality.

Born on May 2, 1892, the eldest of his family’s three sons, Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen’s career in the military was inevitable. He was enrolled in the military school at Wahlstatt at age 11, following the wishes of his father, a Prussian nobleman whose own active military career had been cut short by deafness. There, he excelled in sports but fell behind academically, working just enough to get by in an environment he disliked.

Six years later, Richthofen attended the Royal Military Academy at Lichterfelde, which he enjoyed more. There he warmed up to the idea of life in the military and was determined to apply his riding skills to become a cavalry officer. After a short time at the Berlin War Academy, he was commissioned an officer in the 1st Regiment of Uhlans Kaiser Alexander III in April 1911.

The following year he was promoted to Leutnant, and was still participating in regiment horse jumping and racing competitions when World War I broke out in August 1914. Richthofen went into battle with the Uhlans in the early months of the war, and saw action at Verdun. But as static trench warfare set in, the cavalry became obsolete. He served as a messenger during the winter of 1914-15 and saw some combat, but he felt there was no glory to be had crawling through muddy trenches and shell holes. Having had his fill of unromantic ground warfare, Richthofen wrote to his commanding general to request a transfer to the air service.

Richthofen knew nothing of flying or air combat and, like many infantrymen, had held aviators in contempt. But now the air offered him a new war, one not restricted by an immobile front line. Richthofen’s transfer was approved. Worried that the war would end before he had a chance to see action in the air, he decided to train as an observer. Pilots were required to undergo three months of training, whareas Richthofen, as an observer, was ready for the field in four weeks.

Sent to Grossenhain on June 10, 1915, Richthofen was the first of his training class to be assigned. He began his flying career at Feldfiegerabtedung 69 as an observer on the Eastern Front, taking photographs of Russian troop positions. A couple of months later, he transferred to a Western Front unit in Belgium (later to become Kampfgeschwader I) as a bombardier.

Richthofen had enjoyed flying from the first moment he took to the air during training. His love of flight was further enhanced by watching the bombs he dropped explode on enemy targets. His fascination with seeing the damage he was inflicting earned him his first war wound. Frantically signaling to his pilot to bank for a clear view after dropping a load on a village near Dunkirk, he accidentally dipped his hand into one of the bomber’s whirling propellers and lost the tip of a finger.

In September 1915, Richthofen had his initial tries at air-to-air combat, both times firing on Allied Farman biplanes. The first was an exchange of shots between observers without result. The second encounter ended with the French plane dropping away and crashing after being hit by a couple of bursts of machine-gun fire. Richthofen did not receive credit for the victory because the plane had fallen behind enemy lines, robbing him of any physical evidence.

After June 1915, the Fokker Eindekker monoplane series became the most feared aircraft in the air. Equipped with synchronized machine guns that could fire through the propeller arc without damaging the plane, they gave German scout pilots a firm advantage in air combat. With his new assignment at Kampfgeschwader 11, Richthofen hoped to get a crack at piloting his own plane. Still flying as an observer, he prevailed upon his friend Oberleutnant Georg Zeumer for help. Zeumer was an experienced pilot, and Richthofen had often flown as his observer ever since the two were first teamed on the Eastern Front. After only 24 hours of Zeumer’s tutoring, Richthofen took to the air on his first solo flight, and promptly destroyed his plane while trying to land.

Unwounded and undeterred, Richthofen kept at it, practicing for two weeks before heading off to the flying school at Doberitz. Five months later, he returned to his squadron as a pilot, flying Albatros two-seaters near Verdun. They were not the monoplane scouts he had been hoping for, but once he had fixed a gun to the upper wing of his plane, he was able to both fly and take offensive action. April 26, 1916, saw his second kill, a French Nieuport, go down near Fort de Douaumontagain behind enemy lines, and again not officially counted.

Fokker monoplanes, although successful, were rare at the time. Only Germany’s top aces like Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke were equipped with those aircraft. When Richthofen finally got a chance to fly a single-seat scout it was on shared time, with him using it mornings and another pilot flying it afternoons. The Fokker did not give him the success he had expected, and neither pilot did well with their mount. After the second pilot crashed it in no man’s land, Richthofen was given another, only to crash that one himself.

Boelcke was Germany’s top ace at the time and easily its most respected aviator. Richthofen had met him initially aboard a train while traveling to flying school. The two met again when Richthofen’s squadron was returned to the Eastern Front. Boelcke was touring the area in August, assembling pilots for his new Jagdstaffeln. Happy, but not wholly content flying bombers and attacking Russian infantry and cavalry with machinegun fire, Richthofen jumped at Boelcke’s offer to join him on the Somme to at last become a full-fledged fighter pilot. He left three days later, and reported for duty back on the Western Front on September 1, 1916.

By then, the monoplanes had lost any advantage they once held. They were now being met in the air by improved Allied scouts also capable of forward firing through the propeller arc. German factories were busy turning out better combat fighters — biplane scouts that feature two front-firing guns. While Jagdstaffel 2 awaited delivery of these aircraft for its new fighter pilots, Boelcke trained the men under him in the ways of aerial combat. By the time some Albatros D.II biplanes arrived on the 16th, the pilots were ready for action. The very next day, Richthofen scored his first confirmed kill.

Diving out of the sun with the rest of Boelcke’s squadron on September 17, Richthofen chose an F E.2b two-seater as his target. His inexperience allowed the Allied observer to get off some dangerous bursts at him, but he finally managed to close in and riddle the belly of the Allied plane. He followed the crippled plane down to the ground and landed near it. He watched German soldiers lift the two mortally wounded British aviators from their cockpits. The observer, seeing Richthofen and recognizing him as the victor, acknowledged him with a smile before dying. The pilot never regained consciousness and died on the way to the hospital.

An avid collector of trophies from the hunt, Richthofen started a personal tradition by ordering a small, engraved silver cup to commemorate his victory. He would do the acme for the ones that followed soon after. By October 10, he had claimed his place among the German aces with his fifth kill. His victory tally rose at a slow but steady rate, although everything did not always go smoothly. On October 25, he was certain he had recorded his seventh confirmed kill. Much to his displeasure, this victory was contested by two other pilots who claimed the downed B.E. 12 as their own. Richthofen insisted there had been no other German planes in the vicinity until after the enemy machine had crashed south of Bapaume. Nevertheless, his claim was disallowed, despite evidence in his favor.

Jasta 2, while distinguishing itself as a top fighter squadron, suffered heavy casualties. Half of its pilots and planes were lost to enemy fire, and other fliers suffered nervous collapse from the strain of battle. Its greatest setback, however, came on October 28. Two days after his 40th victory, Boelcke took to the air with five other planes in his flight. Richthofen flew at his right wing, Boelcke’s friend Erwin Bohme at his left. Details vary as to what happened once they engaged two de Havilland Scouts. Some accounts blame Richthofen’s enthusiasm for causing a collision while diving into combat. Others suggest it was Bohme’s shaky skills, or merely the confusion of the chase, that sent one plane grinding against the other. What is known for certain is that for one reason or another the undercarriage of Bohme’s Albatros scraped across Boelcke’s upper wing, causing him to lose control of the aircraft. The damaged wing tore away as Boelcke descended, and his plane crashed, crushing his head on impact. Overwhelmed with guilt, Bohme was inconsolable. At Boelcke’s grand funeral in Cambrai on the 31st, Richthofen carried his mentor’s decorations on a black pillow in the procession. With Boelcke’s death and that of Max Immelmann before him, Germany had lost her top aces. But as Richthofen continued to increase his number of victories, it became apparent that he might fill their shoes. Encouraging him to become Germany’s next aviation hero, officials were less strict about confirming his victories, taking him at his word for the few victims that fell behind enemy lines.

One of Richthofen’s most famous air battles took place almost a month after Boelcke’s death. On November 23, 1916, he went up against Major Lanoe George Hawker, the well-respected commander of No. 24 Squadron, Royal Flying Corps, who had nine air victories and a Victoria Cross to his name. Hawker was in a four-plane flight, led by Captain J.O. Andrews, that attacked five Albatroses south of Bapaume. When the four DH-2s crossed the front lines into German territory, Hawker suddenly found himself alone. Two British planes had had to turn back with engine trouble, and Andrews had quickly joined them after being hit and suffering an engine misfire.

Hawker chose his target. As luck would have it, it was Richthofen’s Albatros D.II. He dove at the Albatros from behind, getting off a five-round burst that missed when Richthofen cut sharply left. Hawker followed him into the turn. The equally matched pilots began a frantic, spinning chase as each tried to outturn the other and maneuver into position for a clear shot. Their tight circle, less than 300 feet in diameter, slowly descended from an altitude of almost 10,000 feet to nearly treetop level.

Hawker was now at a disadvantage. Dangerously low on the German side of the lines, he knew he would be hit from the ground or forced to land if he did not end the battle quickly. A succession of loops, which Richthofen’s less-creative fly style could not match, placed awker in a position to get off another burst that came close, but missed the Baron’s plane. Losing his chance, Hawker turned and bolted for his side of the lines with Richthofen in pursuit.

With both the Baron and the ground closing in on him, Hawker zigzagged at high speed to stay out of the line of fire. He was nearly saved when Richthofen’s first burst jammed his gun. The jam quickly cleared, however, and with his second burst Richthofen shot Hawker through the back of the head. His DH-2 pitched up and then nosed into the ground, just 50 yards short of the German front-line trenches. Richthofen claimed Hawker’s Lewis gun from the wreck as a trophy and hung it above the door of his quarters. Hawker was confirmed as Richthofen’s 11th victory.

The new year marked a series of successes for Richthofen. With his 16th victory on January 4, 1917, he became the leading living German ace. Along with this latest victory came his reassignment as leader of Jagdstaffel 11 at Douai. Two days later, notification came that he was at last to be awarded the Orden Pour le Merite, the ‘Blue Max,’ Germany’s highest military medal. To further distinguish himself from his fellow fighter pilots, Richthofen started painting sections of his aircraft red, possibly after the colors of his old Uhlan regiment.

Jasta 11, although founded around the same time as Jasta 2, held none of the prestige of Richthofen’s old squadron, which had come to be known as Jasta Boelcke. Since its formation in September 1916, his new unit had not scored a single victory, and it fell upon Richthofen to whip the 12 officers under him into shape. Command did not come easily to him, but he sought to follow in Boelcke’s footsteps. Leading by example, he shot down the squadron’s first enemy aircraft shortly after his arrival, on January 23, 1917.

Richthofen’s red Albatros, now the newer D.III, was already making a name for itself among the Allies. The two-man crew of a British F.E.2b, forced to land as the Baron’s 18th victory, referred to ‘le petit rouge’ that had brought them down. It was on this same flight that one of the wings of Richthofen’s plane cracked, and he had to quickly descend 900 feet for an emergency landing. Another F.E.2b that had fired on him claimed this as a victory, but the wing damage could have been due to structural failure rather than a lucky shot.

With success came fame, and Richthofen’s good fortune in combat was milked by the German propaganda machine for all it was worth. Picture postcards and newspaper articles about him circulated widely, and correspondence arrived at his airfield from all over Germany-mostly fan letters from adoring women. The Red Baron had become Germany’s number one war hero.

March and April of 1917 saw a thrust of German air power near Arras against Allied forces that outnumbered the Germans by an average of 3 to 1. Jasta 11 was in the thick of it, and those two months saw Richthofen bring down another 31 aircraft, surpassing Boelcke’s old record. Under his tutelage, the pilots of Jasta 11 were fast improving, and competition between them and the fliers of Jasta Boelcke was friendly but fierce. Allied fliers began referring to Richthofen’s squadron as the ‘Flying Circus’ because of its brightly colored planes, highlighted in red to match their leader’s.

During this period, Richthofen had two close calls. The first occurred shortly after his 25th victory, when enemy fire ruptured his fuel tanks and forced him to shut off his engine, lest it explode, and land near Henin Lietard. April 2 saw another near miss when (according to Richthofen) he was fired upon and hit from the ground by the observer of a Sopwith 1 1/2 Strutter two-seater he had just brought down near Givenchy. In his first report, Richthofen claims to have returned fire and killed the observer, although later he said he held back and did not shoot again despite the dying observer’s attack.

The surviving British pilot, however, insisted that his observer was in no condition to fire after their plane hit the ground. Werner Voss, Richthofen’s friend and competitor from Jasta Boelcke, saw the incident and was cited as a witness to Richthofen’s restraint from shooting. The uncertainty of this exchange remains the only blemish on Richthofen’s record for chivalry in combat.

By the time Richthofen went on well deserved leave in May, he had led Jasta I I to more than 100 victories. Lothar von Richthofen, since joining the air service in his brother Manfred’s footsteps, had also done well. Within a month of j ining up with his brother’s squadron, he, too, had made a name for himself with 20 victories, He was left in charge of Jasta 11 while Manfred toured Germany, meeting with the kaiser and other dignitaries, as well as hunting animals and visiting his mother at home in Schweidnitz.

Richthofen returned to the front on June 14 with new orders to organize four Jagdstaffeln into a single wing. Jastas 4, 6, 10 and 11 became Jagdgeschwader I (JG.I). As Richthofen assumed command as Rittmeister of JG.I in the Courtrai region, he passed on his command of Jasta 11 to Leutnant Kurt Wolff.

While leading Jasta 11 as its JG.I commander on July 6, Richthofen became involved in an epic dogfight with the British that quickly escalated until there were as many as 40 aircraft involved. A chance shot from an F.E.2d, 1,200 feet away, cleaved a 2-inch-long groove in Richthofen’s skull. He was temporarily paralyzed and blinded, and his Albatros fell out of control. Finally regaining the use of his limbs a few thousand feet above the ground, he cut the engine, tore his goggles off, and looked directly at the sun in an effort to clear his vision.

Realizing he was behind the German lines, once he regained his sight, Richthofen restarted his engine at 150 feet and searched for a suitable place to set down. Losing his strength and blacking out, he was finally forced to make an emergency landing. The airplane tore down some telephone wires before it came to a rest, and Richthofen tumbled out of his cockpit. He was still conscious when aid came and transported him to St. Nicholas’ Hospital in Courtrai.

Despite his nearly fatal wound, Richthofen put himself back on duty at JG.I less than three weeks later, against doctors’ recommendations. He was plagued by headaches from the bone fragments still lodged under his scalp and by nausea during flight. But he fought on, all the while insisting that Lothar, also wounded in battle, should not return until fully recovered.

The end of August 1917 saw the arrival of new Fokker F.I triplanes at Courtrai. Richthofen and Voss were among the first to take them into combat. Trading in the Albatros D.V for what would become his most famous mount, Richthofen shot down his 60th plane, an RE-8, on September 1, 1917. It was the last victory he could commemorate with a trophy cup. Silver was becoming scarce in Germany, and Richthofen was forced to discontinue this practice.

The victories he scored after his return to duty failed to inspire Richthofen. After his head wound, he lost much of his zest for combat, and his friends noticed a distinct change in his personality. Already a loner, he became even more withdrawn. Killing was no longer the sport it once had been for him. On September 6, still troubled by his head wound, Richthofen took a period of convalescence to recover more fully. In his absence, his first triplane mount was shot down on September 15, as Kurt Wolff piloted it against a squadron of Sopwith Camels. Voss also met his end in another Fokker F.I during an epic battle on the day of his 48th victory, September 23, outnumbered by a swarm of S.E.5a fighters of No. 56 Squadron led by Major James TB. McCudden. But Richthofen was back at JG.1 on October 23, after visiting home, hunting, recuperating, and finishing writing about air combat in his autobiography.

He shot down a couple more planes on his return, once again flying an Albatros D.V. He then continued inspecting and testing other aircraft that might fare better than the Fokker triplane — whose safety and suitability in the face of new Allied fighters was already being questioned. Because of official noncombat duties and leave, Richthofen was not able to add to his score again until March 12, 1918, once more flying the Dr. 1, as the Fokker triplane was now designated. Between then and April 20, Richthofen downed his last 16 planes, mostly fighters. The final two victories, Sopwith Camels of No. 3 Squadron, came after the Flying Circus was moved to desolate Cappy.

Richthofen led his flight of triplanes to search for British observation aircraft on the morning of Sunday, April 21, 1918. Four triplanes from Jasta 5 were fired on from the ground around 10:30 a.m., after attacking two R.E.8s from No. 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps. The antiaircraft fire drew the attention of a flight of Sopwith Camels led by Canadian Royal Air Force pilot Captain Arthur Roy Brown from No. 209 Squadron. Soon after the Camels intercepted and shot down one of the Jasta 5 planes, Richthofen’s flight joined in the battle.

On the fringe of the fight was Roy Brown’s friend Lieutenant Wilfred R. May, a fellow Canadian. May was a novice pilot, and this was his first offensive patrol. He had been ordered to keep out of combat, but he could not resist going after an enemy triplane that passed close by. He jammed his Vickers guns after firing them too long, and, defenseless, headed away from the battle toward the Somme Valley.

Richthofen, from above, spotted the lone plane breaking off and chose it for his next victim. Brown, seeing this chase unfolding a few thousand feet below him, dove to help his fellow airman. He realized that the lone Camel stood little chance with the red triplane hot on its tail. May, panicking and losing altitude, tried every wild maneuver he could think of to stay out of the Baron’s sights. It was only the unpredictability of the inexperienced pilot’s maneuvers that kept Richthofen from picking him off quickly with his probing bursts.

‘Richthofen was giving me burst after burst from his Spandau machine guns. The only thing that saved me was my awful flying. I didn’t know what I was doing,’ May would say later.

It was then, with Brown closing from behind, that Richthofen, usually a meticulous and disciplined fighter pilot, made a mistake and broke one of his own rules by following May too long, too far and too low into enemy territory. Two miles behind the Allied lines, as Brown caught up with Richthofen and fired, the chase passed over the machine-gun nests of the 53rd Battery, Australian Field Artillery. Sergeant C.D. Popkin opened fire with his Vickers, followed by gunners William Evans and Robert Buie, plus a number of riflemen.

Richthofen was hit, but the debate over who fired the shot that passed through his torso, killing him, goes on. None of the principal shooters ever said with certainty that he was the one who got him. Those who defended the shooters’ claims were their friends and colleagues, choosing sides based more on nationality and emotion than hard evidence.

Top Canadian ace Billy Bishop is one who supported his countryman, saying, ‘Nobody will ever convince anyone who flew in World War I that anyone but Roy Brown shot down Richthofen.’ He also suggested a bias against Canadian fliers, ‘Had he been in any other air force he would have been given credit and would probably have received half a dozen decorations from his own and other countries.’

Whether hit from the air or the ground, Richthofen was mortally wounded. He tore off his goggles, opened the throttle briefly, then cut off the engine and dipped down for a crash landing. His plane bounced once, breaking the propeller, and settled in a beet field alongside the Bray — Corbie road near Sailley-le-Sac. He died moments later. It was 10:50 a.m.

Manfred von Richthofen was laid to rest late in the afternoon of April 22 in a small, unkempt cemetery in Bertangles. He was buried with full military honors after a short service by an Anglican chaplain. Twelve men from No. 3 Squadron, Australian Flying Corps, each fired three rounds into the air. Other officers placed wreaths on the grave. The body was set with feet facing the marker, a four-bladed propeller trimmed to form a cross. Upset about a German being buried in their cemetery, the villagers descended on the grave that night, uprooted the marker and tried to dig up the body.

That same evening, RAF pilots dropped canisters containing news of Richthofen’s death and pictures of his funeral over Jagdgeschwader I, confirming the fears of the German officers there. Oberleutnant Wilhelm Reinhard succeeded Richthofen as commander of JG.I, as per Richthofen’s wishes, but he only lasted two months; Oberleutnant Hermann Wilhelm Goring assumed command after Reinhard’s death.

Richthofen’s body was moved after the war to a larger cemetery at Fricourt. His brother Karl Bolko had his body moved again in 1925, this time to Berlin, where, in a large state funeral with thousands in the procession, he was buried at Fnvaliden Cemetery. A modest flat memorial stone was unveiled the following year by his mother. Goring added a monument in 1938. All the Red Baron’s war trophies, an impressive collection kept at his home, were lost when the Russians advanced through Schweidnitz near the end of World War II.

It has been more than eight decades since Manfred von Richthofen died in battle, but the legend of the Red Baron still retains its fascination. There was much regret from both sides that he did not survive the war. But his death, as much as his life, assured his continued presence in history as one of World War I’s greatest enigmas.

Manfred von Richthofen spent most or World War I flying Albatros biplanes, but he is still most readily associated with the Fokker Dr.I triplane that he made famous.

The tendency of the Albatros D.III’s single-spar lower wing to break off in flight had nearly cost Richthofen his life on January 24, 1917. When it happened again, on April 8 to one of his subordinates, Richthofen was inspired to write a harsh letter to the engineering department in Berlin. He also outlined his specific criticisms of the D.III and enumerated the qualities that made for a good fighter scout.

That month, Dutch designer Anthony Fokker, noted for his aircraft designs for the German war machine and for his development of the interrupter gear for synchronized forward-firing machine guns, visited Richthofen at Jasta 11. Together they went out to the trenches to watch the British Sopwith Triplane in action. It was believed that the three wings gave an airplane more maneuverability and greater climbing ability. Richthofen wanted a comparable design.

Technical reports from captured Sopwiths were unavailable at the time, but Fokker went ahead anyway, modifying one of his biplane designs into a triplane, which he initially designated the Fokker V.3, in three months. The production order was granted July 14, and the F.I, as it was now called, passed its acceptance tests on August 16. Richthofen had the first two combat-ready planes at Jagdgeshwader I on August 21. Later, improved production triplanes were redesigned Fokker Dr.Is.

Slow but nimble, the Fokker Dr.I was the climber that Richthofen had wanted, able to reach 13,000 feet in just 11 minutes. Nineteen feet long, 9 feet high, with a top wing spanning 23 feet 7 inches, it was a small plane. Twin Spandau machine guns, controlled by two separate buttons on the control stick, fired over a nose that many said resembled a face. The Fokker Dr.I, however, was 35 mph slower than the Span 13, and was even outrun by some of the British bombers, such as the de Havilland DH-4.

Two Incidents of the Dr.I’s losing its top wing at. the end of October grounded it until a strengthened wing cleared it for use a month later. Other lesser incidents in the early months of 1918 shed further doubt on the structural integrity of the plane, but poor quality control proved to be the problem. After a government crackdown on Fokker, the reliability of his Dr.Is improved.

Other German aces who distinguished themselves in the Dr.I included Eric Lowenhardt, Lothar von Richthofen, Werner Voss, Ernst Udet, and Josef Jacobs. But it was Manfred von Richthofen, despite flying the plane for a total of only six weeks, who forever made it his own. He flew five different Dr.Is in combat, all of them marked in red, but only one that was totally red. Nineteen of his 80 victories were scored in the Fokker. Richthofen died in a Dr.I while pursuing what would have been another win for himself and the triplane.

Never widely used by other airmen, and quickly out-dated, the Fokker Dr.I nevertheless proved itself the mount of choice for some of Germany’s top fliers—men whose skills could overcome the plane’s shortcomings and use its better qualities to full advantage.

Shane Simmons is a writer and artist who works out of his home on the island of Montreal. For further reading, he recommends: Manfred von Richthofen: The Man and the Aircraft He Flew, by David Baker; The Red Baron: An Autobiography of the Most Famous Air Ace of WWI, by Manfred Freiherr von Richthofen; and The Fokker Triplane, by Alex Imrie.

This feature first appeared in the July 1995 issue of Aviation History. For more great articles subscribe today!